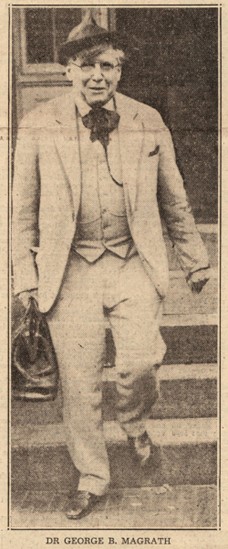

It was the eleventh day of December of the year 1938 when Dr. George Burgess Magrath passed away. He was a great doctor that influenced many individuals in the field of legal medicine and in the “detection of crime.” But there was one person whom he influenced the most. Frances Glessner Lee, friend of Magrath for nearly thirty years, accomplished great feats for her time and carried on the legacy of her dear friend.1

From a young age, Frances Glessner Lee, a Chicago heiress, was enthralled with the idea of solving crimes. She was an avid fan of Edgar Allen Poe, who wrote pieces that were some of the first “detective stories,” and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, with his famous detective Sherlock Holmes.2 Because of this, she admired the fields of law and medicine greatly, and wanted to pursue an education in them. Unfortunately, Lee had many challenges to overcome, one being going into a male-dominated workforce. During the early 1900s, there were still many negative opinions about women working.3 Still, the greatest challenge Lee faced was her own father, John Jacob Glessner. John Glessner, Lee’s personal “jailer” as she liked to call him, intercepted her path in pursuing an education in forensic science. Because of this, she had no choice but to accept that there was no chance of achieving her dreams.4

That was until she encountered George Burgess Magrath, a college friend of her older brother from Harvard University. Magrath, who was working as a medical examiner by the time the two met in 1929, captivated Lee with his tales of investigating deaths.5 As they talked, they discussed many facets of the coroner position, including the influence of politics on the job and the insufficient training both medical examiners and detectives received on the topic of crime investigations. With their conversation and Magrath’s encouragement, Lee was finally given the push she needed to pursue her “fascination with policing and her commitment to the use of medical science in criminal investigation.”6

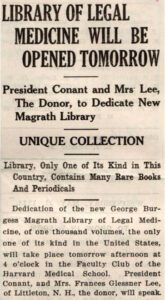

After her initial encounter with Magrath, Lee’s passion for criminal investigation increased tenfold. Although Lee didn’t go to a university, as she was home educated, she dedicated herself to “reading up on criminology and collecting books and papers on the subject.”7 Magrath continued to help Lee become more involved in the forensic scene by introducing her to Dr. Alan Gregg, the chairman of the Rockefeller Foundation’s General Education Board. This foundation was “committed to advancing and professionalizing forensic medicine.”8 By the year 1931, Lee’s continued financial contributions to and advisement of the Rockefeller Foundation helped establish the first Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard University, with Magrath as its first chair.9 In 1934, she donated 1,000 books to establish a library in Magrath’s honor, named the George Burgess Magrath Library of Legal Medicine.10

After her father’s death in 1936, Lee inherited a large portion of his estate, which she used to donate $250,000 to Harvard University’s Department of Legal Medicine.11 For the next few years, the department flourished under Lee’s donations, and it helped train students to become medical examiners. During that time, both Lee and Magrath revelled in their accomplishments until December 11, 1938: the day Magrath passed away. For Lee, that time had been especially difficult, as she lost her closest friend. Still, that did not stop her from continuing forward. Instead, her resolve to improve the process of criminal investigation was strengthened.12

As Lee saw it, something had to be done to advance the techniques of criminal investigation. The sub-par training in medical examination, which was lacking in both medical training and appropriate credentials, could not continue.13 So, she devised a plan that would not only educate students to be more fastidious at crime scenes, but would go on to teach thousands of students for years to come.14 She called this idea the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.” These “studies” were eighteen intricate, handcrafted models, or miniatures as she called them, of different “crime scenes.”15 Some of these miniatures were based on real investigations and others based on pure imagination.16

To bring these studies to life, Lee acquired the assistance of two men: a carpenter by the name of Ralph Mosher and, later, his son Alton Mosher. They helped stage her Nutshells by creating foundations and furniture.17 While the Moshers helped build the miniatures, Lee created the “victims” for her numerous crime scenes by hand, meticulously adding important details to the dolls she made.18

These models were designed to competently train police officers in “the art of crime scene investigation” and to be used as tools for future crime scene investigators.19 They were also used to emphasize an important principal in forensic investigation: “to convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.”20

Starting the building process of the miniatures in the 1940s, Lee, along with Mosher and his son, created three Nutshells every year. After the initial Nutshells were created, they were introduced to a biannual seminar that started in 1946, called the Harvard Associates of Police Science. These seminars were hosted by Lee to give students, police officers, and other law professionals the opportunity to harness their investigation skills by gathering clues from miniature crime scenes.21 During these ninety-minute challenges presented by Lee, all participants were given official “reports” of the study and its “witnesses.” These reports, which were filled with information correlating to the miniatures, were meant to give students the sense of examining a real crime scene. Participants exercised their skills in observation, note-taking, reporting, and depicting the scenes in front of them.22

With the introduction of the Nutshell Studies to her seminars, Lee facilitated improvement in the forensic science world by training of police officers in crime scene investigations.23 For years, her Nutshell Studies would continue to be used in seminars. Even after her death in 1962, Lee’s teachings were referenced throughout numerous works, such as Katherine Biber’s paper “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archives of Domestic Homicide.” She also increased the awareness of numerous social problems in the twentieth century through her dioramas, since they often reflected issues including domestic violence, “social paranoia, questions of the safety of new suburban neighborhoods, and the changing role of women in the home.”24 Lee even influenced much of twentieth-century crime literature and crime films, such as author Erle Stanley Gardner’s novel the Case of the Dubious Bridegroom and Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rope.25 With this influence, Lee was able to accomplish her dreams and foster the improvement of the field of forensic science.

- William Tyre, “George Burgess Magrath: A Tribute,” Glessner House, December 11, 2018, https://www.glessnerhouse.org/story-of-a-house/2018/12/11/george-burgess-magrath-a-tribute. ↵

- Courtney Leigh Harris, “Reflecting their Time: The »Nutshell Studies« of Unexplained Death as Microcosms of Mid-Century America,” Denkste: Puppe 2, no. 1 (September 1, 2019): 34-42. ↵

- Katherine Biber, “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archive of Domestic Homicide,” Open publications of UTS Scholars; January 1, 2019, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/138147. ↵

- Leslie Landrigan, “The Nutshell Studies: Frances Glessner Lee and the Dollhouses of Death,” New England Historical Society, January 31, 2021, https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/the-nutshell-studies-frances-glessner-lee-and-the-dollhouses-of-death/. ↵

- Leslie Landrigan, “The Nutshell Studies: Frances Glessner Lee and the Dollhouses of Death,” New England Historical Society, January 31, 2021, https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/the-nutshell-studies-frances-glessner-lee-and-the-dollhouses-of-death/. ↵

- Katherine Biber, “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archive of Domestic Homicide,” Open publications of UTS Scholars; January 1, 2019, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/138147. ↵

- Leslie Landrigan, “The Nutshell Studies: Frances Glessner Lee and the Dollhouses of Death,” New England Historical Society, January 31, 2021, https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/the-nutshell-studies-frances-glessner-lee-and-the-dollhouses-of-death/. ↵

- Katherine Biber, “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archive of Domestic Homicide,” Open publications of UTS Scholars; January 1, 2019, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/138147. ↵

- Katherine Biber, “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archive of Domestic Homicide,” Open publications of UTS Scholars; January 1, 2019, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/138147. ↵

- Katherine Ramsland, “The Truth in a Nutshell,” Forensic Examiner 17, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 16-18, 20, https://www.proquest.com/docview/207654622/abstract/5656E7B7F1594E37PQ/1. ↵

- Katherine Biber, “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archive of Domestic Homicide,” Open publications of UTS Scholars; January 1, 2019, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/138147. ↵

- Jennifer Davis, “Frances Glessner Lee’s ‘Nutshell Studies in Unexplained Death | In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress,” Library of Congress, September 27, 2022, //blogs.loc.gov./law/2022/09/frances-glessner-lee-and-the-nutshell-studies-of-unexplained-death/. ↵

- Courtney Leigh Harris, “Reflecting their Time: The »Nutshell Studies« of Unexplained Death as Microcosms of Mid-Century America,” Denkste: Puppe 2, no. 1 (September 1, 2019): 34-42, https://discovery.ebsco.com/c/cxw37y/details/2ieaue7mdn?limiters=FT1%3AY%2CRV%3AY%2CFT%3AY&q=Frances%20Glessner%20Lee. ↵

- Katherine Ramsland, “The Truth in a Nutshell,” Forensic Examiner 17, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 16-18, 20. ↵

- Katherine Biber, “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archive of Domestic Homicide,” Open publications of UTS Scholars; January 1, 2019, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/138147. ↵

- Courtney Leigh Harris, “Reflecting their Time: The »Nutshell Studies« of Unexplained Death as Microcosms of Mid-Century America,” Denkste: Puppe 2, no. 1 (September 1, 2019): 34-42, https://discovery.ebsco.com/c/cxw37y/details/2ieaue7mdn?limiters=FT1%3AY%2CRV%3AY%2CFT%3AY&q=Frances%20Glessner%20Lee. ↵

- Jennifer Davis, “Frances Glessner Lee’s ‘Nutshell Studies in Unexplained Death | In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress,” Library of Congress, September 27, 2022, //blogs.loc.gov./law/2022/09/frances-glessner-lee-and-the-nutshell-studies-of-unexplained-death/. ↵

- Katherine Biber, “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archive of Domestic Homicide,” Open publications of UTS Scholars; January 1, 2019, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/138147. ↵

- Courtney Leigh Harris, “Reflecting their Time: The »Nutshell Studies« of Unexplained Death as Microcosms of Mid-Century America,” Denkste: Puppe 2, no. 1 (September 1, 2019): 34-42. ↵

- Clare Brant, “Death in a Nutshell: Frances Glessner Lee’s ‘Nutshell Studies in Unexplained Death,’” European Journal of Life Writing 9 (July 6, 2020): CM85-LWD.CM89, https://doi.org/10.21827/ejlw.9.36936. ↵

- Katherine Ramsland, “The Truth in a Nutshell,” Forensic Examiner 17, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 16-18, 20, https://www.proquest.com/docview/207654622/abstract/5656E7B7F1594E37PQ/1. ↵

- Katherine Biber, “Little Clues: Frances Glessner Lee’s Archive of Domestic Homicide,” Open publications of UTS Scholars; January 1, 2019, https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/138147. ↵

- Clare Brant, “Death in a Nutshell: Frances Glessner Lee’s ‘Nutshell Studies in Unexplained Death,’” European Journal of Life Writing 9 (July 6, 2020): CM85-LWD.CM89, https://doi.org/10.21827/ejlw.9.36936. ↵

- Courtney Leigh Harris, “Reflecting their Time: The »Nutshell Studies« of Unexplained Death as Microcosms of Mid-Century America,” Denkste: Puppe 2, no. 1 (September 1, 2019): 34-42. ↵

- Courtney Leigh Harris, “Reflecting their Time: The »Nutshell Studies« of Unexplained Death as Microcosms of Mid-Century America,” Denkste: Puppe 2, no. 1 (September 1, 2019): 34-42. ↵

20 comments

Joseph Frausto

Congratulations on your nomination and on writing a captivating article. I particularly enjoyed the section describing her relationship with George while also acknowledging the difficulty she faced while trying to break in to a male dominated field. Telling the stories of female pioneers in areas such as this is an important step in ensuring future diversity in these fields. Great job!

Karicia Gallegos

Congratulations on your nomination! This was an article on a story I had never heard of that was both highly entertaining and educational. It’s always inspiring to hear about a successful woman, especially at a period when women weren’t taken seriously. It’s incredible to think that she was able to do what she accomplished and alter how crime scenes are taught to future generations. Overall, great job!

Iris Reyna

Congrats on your article nomination Victoria, the article was a very informative and interesting read, I have never heard about Frances Glessner Lee before, or what she accomplished. It was amazing to see what Frances Glessner Lee created and the theories, about the nutshell studies. It was sad to hear about what led her into her path of forensic science/crime. It was the passing of her dear friend George Magrath. It was sad but the death of her friend should not have the impact she made of the forensic science/crime of today. Good Job on the amazing article.

Kristen Leary

Wow, what a very interesting article! I never would have thought to be curious about the history of forensic science, but now I must say that I am. I thought it was an interesting detail that she was interested in mystery novels and books about crime scenes and things relating to that. I really enjoyed reading your article, and you did a great job.

Azeneth Lozano

Wow Victoria, this was a very interesting and informative article about a story I have never heard of. It’s fascinating to learn about Frances Glessner Lee and her story, especially since she was limited in her resources. It is also nice to learn that Lee played a big role in the ideas that created today’s criminal stories and movies. Overall, a well-written informational article, and congratulations on your well-deserved nomination.

Gabriella Parra

Victoria! I’m so excited to have been able to work with you on this article. It turned out great, and I’m glad you were able to get a nomination for your article! I was interested to learn that Frances Glessner Lee was limited in her education. That she achieved what she did by taking her education into her own hands is an amazing feat!

Guiliana Devora

This is an amazing article and the author did a great job of telling it. Congratulations as well on getting a nomination. Hearing a story about a successful women is always amazing, especially in a time when women were not taking serious. To think that she was able to accomplish what she did and change the way people are taught about crime scenes is amazing.

Hunter Stiles

Congrats on your publication. It is comforting to know that Dr. George Burgess Magrath’s friend, Frances Glessner Lee, supported him after his death and worked to further his legacy and achieve so much more. She was fascinated by the concept of resolving crimes and coming from a criminology major. I adore the articles she published about these topics. Particularly given the difficulties she encountered working as a woman herself, which were not particularly favorable at the time, but that didn’t deter her. After not attending school, she committed herself to reading criminology literature and getting acquainted with the field. For years, she was able to motivate and inform kids about the crimes committed. Well written.

Muhammad Hammad Zafar

Amazing, as Lee was passionate about law and forensic science fields and becomes the source of blessings for millions of people by her contributions by understanding the investigations and teaching it.

Danielle Sanchez

Congratulations on your nomination! This article was well written and informative! From a young age, Frances Glessner Lee, a Chicago heiress, was enthralled with the idea of solving crimes. She was an avid fan of Edgar Allen Poe, who wrote pieces that were some of the first “detective stories,” and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, with his famous detective Sherlock Holmes