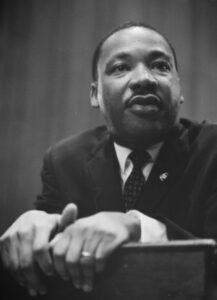

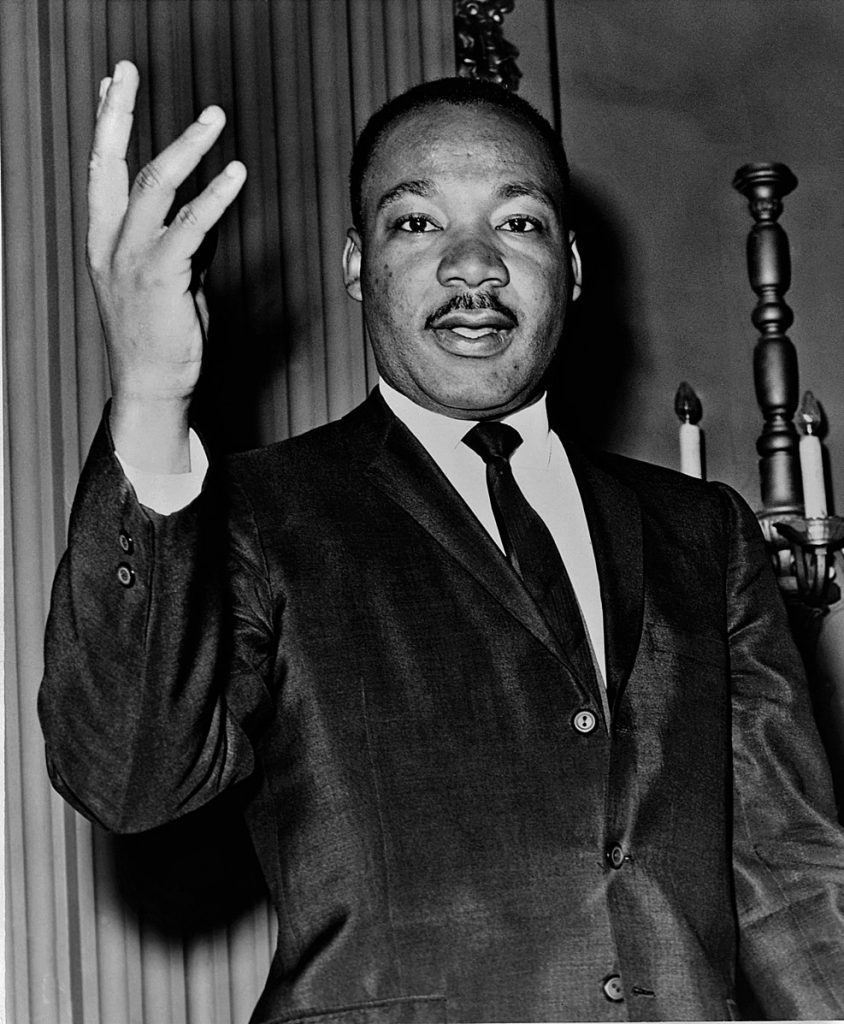

It was the year 1963, the third day in April, when the idea of having a civil rights campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, was brewing and becoming a reality. Martin Luther King, a master in problem-solving and expert in critical thinking, decided to use a particular type of protesting that Mahatma Gandhi influenced which would seem practical in this newly built campaign: non-violent protesting. King became leader of the South Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) around 1957 because of his success in the bus boycott, which displayed outstanding leadership and showed the effect of non-violent protesting. With these tremendous successes and the effectiveness of non-violent protesting, he planned to apply it to the Birmingham Campaign, hoping to destroy the deep-rooted segregation policies that were enforced with excessive violence.1 Birmingham, Alabama, in the 1950s and into the 1960s was one of the worst areas for racism, segregation, and everything you could think of that regarded the horrible treatment of individuals of color. With Martin Luther King’s desire to eliminate segregation and racism not just in Birmingham but everywhere in the United States, this was a significant campaign for him. This was especially important, considering that his challenger was a fierce opponent, the Commissioner of Alabama Eugene “Bull” Connor, who was notorious for using violence to enforce the segregation policies that were taking place. With Martin Luther King Jr. hoping to have some movement in Birmingham, Alabama, he needed to find ways to open the eyes of the people to look at the treatment of African Americans not just in Birmingham, Alabama, but the entire United States and have the realization this is not morally right to treat someone less because of their skin color.2

The campaign was supposed to start in early March 1963, but unfortunately, it was postponed until April 3.3 It was finally becoming a reality, but it was missing one main ingredient. In order to make this protest a campaign, it needed a robust and great-minded leader. There was one man for the job, one who could do the change effectively and had a critical thinking mindset like no other, and that man’s name was Martin Luther King Jr., and his trusted South Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) organization backing him up in any way he needed support. The reasoning for their needing a leader who had a great critical thinking mindset and could accomplish this goal of abolishing segregation was because they were going to take on the most segregated part of America, Birmingham, Alabama, which also had corrupted authority and enforcers that made sure segregation would be forever deep-rooted. Martin Luther King Jr. was greatly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi and how Gandhi contributed to his ambitions by using nonviolence to make India independent from British rule. So, King decided to use nonviolent protesting in his campaign as well. King believed that responding to hate with hate only perpetuated a cycle of violence and that the only way to defeat injustice indeed was through love and nonviolence. This philosophy was put to the test during the Birmingham Campaign, where King and his followers faced violent repression from law enforcement and white supremacists.4

Martin Luther King Jr. wanted the Birmingham campaign to be like a picture painted for people to look at, even from afar, and decide whether it was acceptable or not. For people to decide whether to watch from the sidelines and let these horrible actions continue to these innocent protestors or help make a difference in the world, destroying the racially built wall that was created to divide races. To paint this painting for the world to see, King and his supporters used the media to their advantage by organizing a series of nonviolent protests, boycotts, and sit-ins designed to draw the attention of viewers to the injustices faced by African Americans in the South. The use of nonviolent direct action was not only a planned choice but also a moral one, rooted in King’s belief in the benefits of nonviolence as a means of social change. King used public protests to show viewers the brutality of how black people in America were being treated by showing the abuse in the light of the public instead of in the shadows of jail cells.5

With this image-prone campaign up and moving, these protests were aggravating and making law enforcement angry, especially for “Bull” Connor, who was a commissioner in Birmingham, Alabama, who was the primary enforcer of segregation and wanted these protests, especially this campaign, eradicated because of his racially fixed mindset. Eugene “Bull” Connor achieved his reputation because of how he enforced these policies by using administrative authority over the police and fire departments to ensure that Birmingham remained, as Martin Luther King described it, “the most segregated city in America.”6

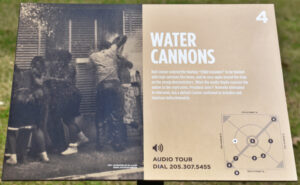

During the campaign, Connor used his resources by sending out police or firefighters to hose down or beat the non-violent protestors. He sadly would even gravely injure the protestors with dogs being called upon. While Martin Luther King Jr. knew of the consequences of the campaign, he wanted the protestors and himself to be gravely injured so that it could be displayed to the world these terrible actions regarding the protestors and law enforcement being a picture painted with blood and injuries. While Martin Luther King also knew about Connor, Connor knew a lot about King and wanted him in prison, leaving his campaign in shambles. So, on April 12, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, and more than fifty-four other protestors were arrested. They were taken to the Birmingham City Jail, where King was placed in solitary confinement.7

While in confinement for eight days, King wrote a letter that has subsequently become known as “The Letter from Birmingham Jail.” The letter was written because while imprisoned, King stumbled across a newspaper article with statements from eight white clergy members that used words like “unwise” and “untimely.” King strongly disagreed with these statements and wanted to explain and argue the reasoning behind his actions. While this influential work was published after Martin Luther King Jr.’s release from jail, it still showed his reasoning for writing the letter during his imprisonment.8

King preached his mind in his letter, explaining that there are so many reasons to have this campaign, especially in Birmingham; he even stated in his letter, “Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial ‘outside agitator’ idea. Anyone living in the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.”9 In his letter, Martin Luther King Jr. emphasizes the urgency of the civil rights issue. He wanted to convey that it’s not just limited to Birmingham but is a nationwide problem that needs to be addressed promptly. King called for immediate action and outlined a clear strategy to achieve this goal, which continues to inspire us even in present times.

The Children’s Crusades were another product of the Birmingham campaign, which became a story during Martin Luther King Jr.’s time in jail. While it did not fully end segregation, it did play a significant role in contributing to its end. It was a new idea to get things moving; it did sound awful that children were coming out to protest, which was frowned upon by other civil rights leaders, but it was a tactic that helped to open the eyes of many. This crusade didn’t happen in one night; it was suggested by Reverend James Luther Bevel’s idea to recruit students, his wife, and civil rights activist Diane Nash.10 Recruiting led to the students influencing their peers to join, which grew the numbers quickly. Many of these students were willing to risk their limited freedom to be arrested for the cause. When King learned of the idea, he rejected this proposal of this becoming a tactic, but it still took place and was led by Rev. Bevel and his wife.11 On May 2, the children’s crusade started, and they began walking into dangerous waters where police were waiting for the protesting children. They were sent to jail on buses because of “Bull” Connor, who ordered these actions to take place. There were around 600 students as young as six years old being detained and shipped off to a juvenile detention facility.12

Martin Luther King Jr. was released on April 20, 1963, and it wasn’t a long, warm welcome out of jail. There was still work that needed to be done. Being released from jail, King led the Civil Rights Movement with determination and resolve, advocating for justice, equality, and civil rights reforms through nonviolent protest and activism. The Children’s Crusade’s contribution to the campaign also helped more people open their eyes, which helped it gain support for the cause. Only one thing was left: opening the eyes of higher powers and negotiations that needed to take place, which, as a result, did happen. President John F. Kennedy decided to be a supporter, which resulted in him announcing his support for federal civil rights legislation to ban discrimination in public areas. Because of continuous violence, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, which prohibited segregation or discrimination.13

The Birmingham Campaign of 1963 will be forever remembered as a media-driven event regarding the civil rights movement that opened the eyes of many, changing perspectives on segregation and racism. This campaign, led by Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the strategies of non-violence that King used, helped make positive changes effectively. This campaign was to display to the public the horrific realization of racism and to call people around the world to take a stand to ensure justice and prosperity among races where there won’t be any more children crusades or innocent people going to jail for fighting for their rights as civilians. The legacy behind this campaign served as a reminder of the importance of non-violence and its effect on social change. It was also a beacon of hope to future generations to ensure positive morality and equality. This powerful tool used by Gandhi and King continues to resonate with activists worldwide for what it stands for and how effectively it is used to combat people with negative mindsets.

- “Nonviolence | The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.” Accessed May 8, 2024. Para.4 https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/nonviolence. ↵

- Davi Johnson, “Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 Birmingham Campaign as Image Event,” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 10, no. 1 (2007): 1, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41940115. ↵

- “Birmingham Campaign,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University, Accessed May 3, 2024. Para.2 https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/birmingham-campaign. ↵

- Deogratias M Rwezaura, “Martin Luther King Jr. and Julius K. Nyerere’s Shared Dreams for Racial Equality and Human Dignity,” Theological Studies 84, no. 3 (January 1, 2023): Para. 10, https://doi.org/10.1177/00405639231189189. ↵

- Davi Johnson, “Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 Birmingham Campaign as Image Event,” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 10, no. 1 (April 1, 2007): 2. ↵

- “Connor, Theophilus Eugene ‘Bull’ | The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.” Para. 1, Accessed May 7, 2024. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/connor-theophilus-eugene-bull. ↵

- “On Apr 12, 1963: Bull Connor Orders Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Dozens More Civil Rights Marchers Violently Arrested in Birmingham,” Para.3, Accessed May 7, 2024. https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/apr/12. ↵

- “Letter from Birmingham Jail | Teaching American History,” accessed May 8, 2024, Para.1 https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/letter-from-birmingham-city-jail-excerpts/. ↵

- “Letter from a Birmingham Jail King, Jr.” Accessed May 3, 2024. Para.4 https://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/Letter_Birmingham.html. ↵

- Adam Volle, “Birmingham Children’s Crusade,” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 25, 2024. Para.5, https://www.britannica.com/event/Birmingham-Childrens-Crusade. ↵

- Adam Volle, “Birmingham Children’s Crusade,” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 25, 2024. Para.6, https://www.britannica.com/event/Birmingham-Childrens-Crusade. ↵

- Adam Volle, “Birmingham Children’s Crusade,” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 25, 2024. Para.8, https://www.britannica.com/event/Birmingham-Childrens-Crusade. ↵

- Adam Volle, “Birmingham Children’s Crusade,” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 25, 2024. Para.11, https://www.britannica.com/event/Birmingham-Childrens-Crusade. ↵

3 comments

Lauren Sahadi

This was a great article on the role of Martin Luther King Jr. in the fight against segregation and racism. I think we’ve heard a lot of stories about Martin Luther King Jr., but you did an awesome job at telling a very important and interesting story. I really liked the set up of the article and the images included. Good job.

Nicholas Pigott

Hi Aden! Your article is an inspiring piece about one of the most inspiring people and campaigns in history. I love how it’s not just about the great Martin Luther King Jr., but also a wider view of the Birmingham campaign. It’s important for the remembrance of peaceful protesting campaigns as social unrest rises with global conflicts happening. MLK Jr. and the participants of Birmingham should remain as every engaged citizen’s role models.

Gaitan Martinez

I greatly appreciate the focus on the Birmingham, Alabama campaign because as the author said, “it was one of the worst places people of color could habit.” Also, I like to inform everyone how when MLK passed away, doctors determined he had a heart of a 60 even though he was 39 years old! I once wrote a paper on how much more effective non-violent protests are compared to violent protests. I don’t remember much, but I do remember there was a significant difference between the success of nonviolent vs the violent.