April 7, 2024

Gaps in time: The Mexican Revolution Through the Eyes of a Female Revolutionary

The Mexican Revolution is undoubtedly one of the most violent yet significant events in Mexican-American history. The decade-long war brought an end to the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, sparking a new age of government reform and establishing a constitutional republic. Though it was destructive, the revolt generated a variety of cultural products ranging from literature to music. However, the documentation of events was heavily concerned with the glorified tales of male revolutionary figures who fought on the frontlines, leaving other stories in the dark to wither away with time. As a result of this emphasis on male-centered narratives in the history of the revolution, the historical accounts of female participation in the war are limited and often disregarded, with their roles being deemed too insignificant in comparison.

Despite this, Leonor Villegas de Magnón revitalized these lost stories and pushed against the overbearing narratives of the revolution to put women and other marginalized groups at the center of the stage through her journalism. The memoir she produced as a result of the historical events she experienced, The Rebel, not only speaks of the rebellion’s events on both sides of the border between Mexico and the U.S. but reframes its masculinized history by recording her and other women’s contributions to the cause. This teacher, revolutionary, and political activist breaks traditional gender roles and unveils the unheard work of those behind the scenes: soldaderas, camp followers, nurses, and journalists. Her story gives answers to how revolutionary armies were so successful and seals the gaps in time left by the erasure of women in history.

Before delving into the work of Magnón as a revolutionary, it is necessary first to give brief context to the history of the Mexican Revolution and Magnón’s place in it. While historians agree there is no true way to date the beginning of a revolution, the catalyst of this violent revolt was likely to be the reelection of President Porfirio Díaz to serve his seventh term in 1910.1 Díaz held office for over three decades, and his authority could only be described as tyrannical and repressive. His administration’s goal was to bring Mexico into a new era of development, which Díaz attempted to bring about by any means possible; elitist economic policies were implemented to facilitate industrialization, later leading to economic inequality, unequal land distribution, and suppression of political rights. Indigenous peoples were affected most by the president’s policies, facing extremely low wages, forced labor, and land seizures.2 With elections rigged and the people of Mexico left feeling powerless to speak against the government, the elections were in Díaz’s favor.

However, an unexpected adversary arose: Francisco Madero, a wealthy rancher who formed a campaign in 1908 to stop the reelection of Díaz. Madero wanted to change Díaz’s government completely and establish a democracy in addition to preventing Díaz from serving a seventh term. Right before he could run in the elections, Madero was arrested for insubordination on June 14th, 1910, and placed in jail at San Luis Potosí. It was here that Madero called for “effective suffrage, no reelection” and sparked the beginning of the revolution.3 The people of Mexico began rallying together in opposition to Díaz’s election, yearning for justice and the death of autocracy.

It was around this time that Leonor Villegas de Magnón first began experiencing the conflict of the Mexican Revolution up close. Before the reelection that launched the revolution into motion, Magnón moved from her home of Laredo to Mexico City in 1901 after getting married to her husband, Adolfo Magnón. It was here that she was first exposed to the elite class in Mexico, and while she was enchanted by the lives of the wealthy initially, she “could never accept it completely, seeing the sorrows and oppression of the poor.” 4 This exposure to the elite as well as the issues faced by the lower class of Mexico caused Magnón to seek an involvement with politics. In The Rebel, she recounts her conversations with General Bernardo Reyes— Díaz’s Minister of War— concerning the problems that faced the government. Magnón claimed to have admired Reyes’ determination regarding the bettering of Mexican soldiers’ treatment and quality of life, and many hoped for him to run against Díaz in the election. Though, Reyes was arrested once Díaz caught word of his plans to succeed him. Magnón and her husband had to flee Mexico City not long after the unjust reelection, which resulted in frequent riots against the print house located near their home.

After seeing the demonstrations and marches led by Madero throughout the streets of Mexico, Magnón became passionate about the revolution’s cause. She first began her participation in the effort by writing for a weekly Spanish newspaper by the name of La Crónica, describing her columns critiquing the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz as “outbursts of patriotism.” 5 Later on in 1912, she helped found the newspaper El Progreso in Laredo, Texas. This newspaper on the border quickly grew in popularity and became a powerful tool for spreading the news from Mexico’s fighting zones. However, Magnón did not stop at her journalism and soon became more heavily involved in the Mexican Revolution after the assassination of Madero, which sparked a major national upheaval.

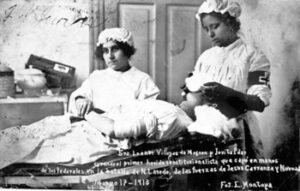

On March 13, 1913, Nuevo Laredo was attacked by General Jesus Carranza after counter-rebelling against Victoriano Huerta— a general in the Mexican Federal Army— after he betrayed Francisco Madero through an armed uprising that led to his capture and murder.6 This event, which had affected her family living in the city, forced Magnón to leap into action, and she began formulating her plan to travel back to Mexico to assist in aiding those wounded in the counterattack. Additionally, El Progreso, as a result of the attack evolved into an anti-Huerta propaganda newspaper and continued providing information about the war. Magnón was accompanied by another writer from El Progreso, Jovita Idar, in her efforts to offer immediate help. It was then that she formed the group La Cruz Blanca (the White Cross), a volunteer infirmary service made to treat rebel soldiers in combat. Nonetheless, Magnón was not just a volunteer nurse for the Carrancista soldiers; she played a key role in organizing escape plans for captured revolutionaries and bailing out those part of the rebellion who were taken into custody. Furthermore, after Constitutionalists launched an attack on federal soldiers on January 1st, 1914, Magnón converted her own home into a makeshift hospital for those wounded by the conflict. It is said that over 100 of Venustiano Carranza’s men were treated by Villegas in the month of the attack.7

However, these considerable contributions of Magnón stayed largely undocumented and unheard of until the much later discovery of her work by Clara Lomas. While in Laredo, Texas, on an archaeological pursuit to study the participation of women in the Mexican Revolution, Lomas recovered various documents and autobiographical literature belonging to Magnón which detailed her experiences in the conflict as well as her political ideas. The artifacts were discovered in the Magnón’s vacant house inside an old family trunk nearly destroyed by burglars and lost to time.8 After documenting the manuscripts, photographs, and scrapbooks with newspaper clippings, Lomas soon realized that its contents were incomplete— they were mere remnants of the materials taken by a publisher who never returned the originals.

According to Lomas, the missing documents were taken after Leonor Grubbs, the daughter of Magnón, attempted to fulfill her mother’s dying wish: to have her autobiography published. Unfortunately, during Magnón’s lifetime, she had tried countless times to publish her historical memoir and was turned down by each. Publishers had refused to publish her work supposedly due to its romanticist literary style, which was considered unusual and non-traditional to the genre of historical literature/autobiographies. Both the Spanish and English versions of The Rebel written by Magnón were largely dismissed and regarded as “novelized memoirs,” despite the plethora of information it provides on the noteworthy events witnessed by Magnón in the revolution. Because of this, Lomas claims that Magnón’s story was “imprisoned… within a narrative form which has historically privileged male authority, authorship and discourse and ignored or devalued those same female qualities.” 9

Her struggle in documenting her own significant contributions to an extremely influential historical event— a battle for publishing that extended much past her lifetime— clearly displays the overbearing dominance of male-centered stories in history. Magnón was well aware of this silencing of female voices regarding the history of the Mexican Revolution in both the United States and Mexico. To combat this and put marginalized stories in the forefront, she repeatedly acknowledges the major roles of the nurses in her brigade as well as the achievements of other women participating in the war. For example, she writes in her memoir of the triumphs of Carmen Sredan, a Mexican revolutionary who shared the ideas of Madero’s cause: “…Serdan became the heroine of the revolution. She ignited the flaming torch that illuminated the path for democracy and hastened the overthrow of President Porfirio Díaz.” 10 Furthermore, Magnón expresses her frustration with the disregard for female revolutionaries such as Serdan, writing that men in the war say much about themselves and forget about the brave women fighting for their cause. Her memoir is not only used as a tool to provide information on the stories of other women like her but heavily criticizes their forgotten contributions as well, effectively rebelling against a narrative form relatively ruled by men.

Magnón does not stop at acknowledging the contributions of other women besides herself in the revolution in reframing its narratives; she speaks on the traumatic violence endured by citizens at the hands of soldiers as well— an aspect of the war often left out. Due to the glamorization and masculinization of its violence, the majority of stories of the Mexican Revolution set the stage for dramatic, climactic tales of men bravely fighting against the oppressive forces of the Mexican government. Stories describing the experiences of female soldiers as well as the wars’ gruesome consequences, especially the violence experienced by women and children, are on the other hand not given as much recognition or publicity. For example, the true brutality of the war can be seen in the work of another female writer by the name of Nellie Campobello, who wrote lyrical memoirs of the violence and barbarity of the revolution: “My eyes had become accustomed to seeing people killed by hot lead that exploded in their bodies. A woman wearing a skirt was left lying on the ground, trussed up like a bundle of clothes. A young boy was placed carefully beside the railway track without a mark on him; he was pale, his eyes open.” 11 Magnón does not shy away from describing the revolution’s viciousness herself, writing in her memoir of the misery it has caused: “In all social upheavals, grafters, demagogues, and wolves of the social body prey upon innocent individuals with insatiable greed that becomes steadily rapacious in its voracity. These people without morals have caused more destruction and grief in the world than all the pestilence mankind has ever endured.” 12 These detailed descriptions, though not written in the ‘style’ of historical literature according to male critics, effectively convey the pain and suffering endured by the people of Mexico as a result of the conflict.

Another way Magnón went against the male-centered history of the revolution and challenged the traditional gender roles of her time was by framing the roles men and women took on in the revolution as equally important— a comparison that remains controversial to this day. Even now, the history of women’s contributions to the Mexican Revolution is brushed off and considered irrelevant in comparison to soldiers fighting on the frontlines, despite female soldiers/nurses acting as the backbone of battalions. According to Andrés Reséndez Fuentes, bringing women and soldaderas was the difference between life and death; for example, Northern revolutionaries neglected to bring female soldiers to battle, which put them at a major disadvantage compared to other brigades. 13 This was likely due to the fact that women acted as nurses and caregivers to the men by providing them with medical assistance, food, ammunition/weapons, and other supplies. In The Rebel, Magnón repeatedly compares herself with her male peers around her, using her writing to depict both their contributions to the cause as equal in importance rather than undermining her own role: “‘So are you not one of us?” he said holding towards her the flag staff they had both advanced to get.” 14 The significance of her participation is further confirmed when one examines the success of the Carrancistas, one of the three largest armies in the revolution. 15 The Carrancistas had ample female volunteers in their battalion— among them being Magnón and her group of nurses— who supported their soldiers, and they would likely not have risen into power without them.

Moreover, Magnón also makes her opinions regarding gender equality and women’s participation in intellectual society abundantly clear through both her journalism and actions. In the articles she wrote for newspapers such as La Cronica and El Progreso, she passionately advocated for equal pay and encouraged the participation of women in the political climate— which at the time was dominated exclusively by men. Throughout her memoir, Magnón expresses her strong feelings towards the restricting gender roles of her society through her bold efforts as a revolutionary. During the early twentieth century, women were expected to act submissive to the men around them and behave in a reserved manner. In her memoir, Magnón characterizes herself as the complete opposite of this, defying the men around her and refusing to follow their orders: “‘You don’t know me. I am a sensible rebel. No one, as yet, has ordered me to do anything. My father, my husband, and my brother always let me do anything.’” 16 Additionally, she is far from afraid to give orders to soldiers and even scolds powerful revolutionary leaders, such as when Venustiano Carranza mistreats one of his men and Magnón responds: “‘You are their standard of hope. But you can do nothing without your followers. There can be no retracing of steps now until you bring peace…’” 17 No matter the situation, Magnón refused to back down and silence herself, a courageous quality atypical of how the ideal woman in twentieth-century society was portrayed. Her strong will and personality alone rebelled against the constraints of the patriarchal society in which she existed.

Nonetheless, Magnón’s memoir The Rebel serves as an especially significant document in the history of the Mexican Revolution as it simultaneously rebels against the male-dominated world of historical literature and unveils the contributions of female revolutionaries that have long gone ignored. Her account of women’s participation in the revolt effectively seals the gaps in the revolution’s history by highlighting the stories of female soldiers responsible for supporting army groups both on and outside of the battlefield. The recorded experiences of this valiant revolutionary are but one of many influential narratives that have been silenced and nearly lost to time, demonstrating the importance of keeping these stories alive by retelling them and creating awareness.

- Frost, Mary Pierce. The Mexican Revolution (San Diego: Lucent Books, 1996),11. ↵

- Knight, Alan. The Mexican Revolution. Vol 1. (University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 8. ↵

- DiPiazza, Daniel D., and Robert D. Talbott. “Mexican Revolution.” Salem Press Encyclopedia, Jan. 2023 ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), 70. ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), 75. ↵

- Matousek, Amanda L. “Leonor Villegas de Magnón and ‘La Otra Trinchera’ of The Mexican Revolution.” (Hispanic Journal, vol. 38, no. 2, 2017), 71. ↵

- Nancy Baker Jones, “Villegas de Magnon, Leonor,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), preface viii-ix. ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), preface xxxi. ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), 79. ↵

- Sosa, Kathy, et al. Revolutionary Women of Texas and Mexico : Portraits of Soldaderas, Saints, and Subversives (Maverick Books, 2020). 35. ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), 172-173. ↵

- Fuentes, Andrés Reséndez. “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution.” The Americas, vol. 51, no. 4, 1995, pp. 525–53. ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), 86. ↵

- Fuentes, Andrés Reséndez. “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution.” The Americas, vol. 51, no. 4, 1995, pp. 525–53. ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), 107. ↵

- de, Magnón, Leonor Villegas. The Rebel, edited by Clara Lomas (Arte Público Press, 1993), 151. ↵

Tags from the story

Biography

Mexican American History

Mexican Revolution

Nomination-Humanities

Nomination-Political-History

Recent Comments

Vianna Villarreal

What a great topic to write an article about. It is so important to see how the Mexican revolution played out in history but also how the different genders were effected. There are many different ways that men and women have been treated in history and though there was a battle for all Mexican citizens I think there is another battle that had to be fought in a completely different form. It was the battle for women to show their ability in society. Great work and very well written article.

24/04/2024

4:29 pm

Madison Hinojosa

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your amazing article. As a Mexican-American, it truly resonated with me how you delicately and insightfully touched on such an important subject. Your perspective sheds light on issues that are often overlooked, and I appreciate the depth you brought to the discussion. It’s always refreshing to see diverse voices represented and valued in such meaningful conversations. Thank you for sharing your insights and promoting inclusivity through your work. Your article serves as a powerful example of the positive impact that inclusive storytelling can have on bridging cultural gaps and fostering understanding among different communities.

27/04/2024

4:29 pm

Jonathan Flores

Wow, this article is truly great. As a Mexican American, I was extremely touched by your dedication to tell the important story of our history. In particular, the approach you took that includes the female perspective, who have historically been discriminated against is truly eye opening. I enjoyed your writing style and feel that you were greatly informative on a great topic. Congratulations on your publication and good work.

23/04/2024

4:29 pm