In 1944, in the small town of Alcolu, South Carolina, Jim Crow laws and segregation were in full force. Not only was the town divided just by the train tracks, putting white Americans on one side and African Americans on the other, but also, it should be noted that the economy of the town heavily relied on the Alcolu mill, which was owned by the wealthy Alderman family, who could have played a key role in the story we are about to hear.

The two girls, Betty June Binnicker (11) and Mary Emma Thames (8)—young white girls on their way to the other side of the train tracks near where the African-American Stinney family lived—wanted to pick maypops, a popular flower at the time that only grew across the train tracks. On their way to look for them, they saw George and Amie Stinney. They pulled off their bikes to talk, and they asked if they had seen any flowers. After this brief conversation, the girls returned to their bikes and headed off. George and Amie watched the girls’ backs on the bikes, slowly watching them disappear in the distance. That day, unfortunately, those two white girls would never be heard from again, and unbeknownst to George and Amie, they would be the last to see those girls alive. That afternoon turned to dusk, and dusk then turned into the night. The two girls’ parents grew increasingly worried; they had not heard from the girls or seen them since they had left for work. By dusk on the horizon, a search party had been formed to go out and look for the girls. But soon, that would seal the fate of George. The search party looked for hours, but the search was quickly ended after they found the girls’ bodies by the train track. The girls’ bodies were inflicted with head wounds: “Thames had a hole boring straight through her forehead into her skull, along with a two-inch-long cut above her right eyebrow. Meanwhile, Binnicker had suffered at least seven blows to the head. It was later noted that the back of her skull was ‘nothing but a mass of crushed bones.'” 1 Young Betty had a bruise around her groin like she had been assaulted, also adding to the idea that there were sexual motives for this attack. However, this idea was never conclusive.

Once the girls were found and the word got out that George Stinney was the last to see these girls, the police went directly to his house to talk to him. Once they arrived at the Stinney family home, they questioned him and his sister, Amie, about the encounter with the girls and what they spoke about when they saw them. George and Amie had told the officers about the encounter with the truth, but that was not enough for them. They soon arrested George. Also, adding to his arrest, his mother and father were not present. Only his siblings were. Along with George, so was his older brother, Johnny, who was seventeen, but he was later released due to lack of cause. Even though his brother was released, George was not. Thus, George was put into an interrogation room alone without his family knowing where he was and with no legal representation. George was questioned and interrogated for hours. There is no clear evidence on what exactly happened in that interrogation room. After the officers had finished interrogating him, they told the public that he had given a verbal confession about killing the girls. Though there were no official records of his questioning, the officers said he confessed to killing the girls over an argument over the flowers that the girls were going to pick. There was no written statement about the confession, so it was all up to the police’s interpretation about his confession.2

The police claimed that George Stinney Jr. confessed to murdering Binnicker and Thames after his plan to have sex with one of the girls failed. An officer named H.S. Newman wrote in a handwritten statement, “I arrested a boy named George Stinney. He then confessed and told me where to find a piece of iron about 15 inches long. He said he put it in a ditch about six feet from the bicycle.”3

Accounts from his cellmates and others from the jail told writers he did not do it and was forced into a confession; some speculate that it was either by force or something worse. Cellmates claimed that George said, “I didn’t do it; I just told them where the flowers were,” through the cell walls. But they knew it was already too late. There are also other accounts from the town that knew it was a cover-up. People knew that George did not commit that crime, but it was pinned on George because the person who committed it was part of a big family that was wealthy and well-known. “A rumor floated around town that the girls had made a stop at a prominent white family’s home on the same day of their murder, but this was never confirmed. And police certainly didn’t seem to be looking for a white killer.”4 George was a target because of his skin, and not only because of that. There was also speculation that there was more to it. His mother worked at the mill, and during a shift there, one of the white supervisors started to flirt with her. She proceeded to reject him, and that set off the revenge aspect of the case.

After George was arrested and his brother was released, his family was evicted from their company home, and his father was fired from his job at the mill. He was advised by others to leave town because there was a search for George and his family. “Newman refused to reveal where Stinney was detained, as rumors of lynching spread throughout the town. Not even his parents knew where he was as his trial quickly approached. They fled out of North Carolina without George, never to step foot in North Carolina again. They were never to see George again.3

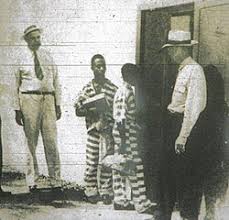

The idea that George had done it made no sense, and it was not until later that the truth would come out. “About a month after the girls’ deaths, George Stinney Jr.’s trial began at a Clarendon County Courthouse. Court-appointed attorney Charles Plowden did ‘little to nothing’ to defend his client.”6 At the trial, there were over 1,500 people at the courthouse, some calling for the sinner’s death and some calling it injustice. George’s family was not able to attend the trial because they were afraid of getting attacked by a white mob and getting lynched. Some accounts say that George arrived at the courthouse, “Sonya’s grandfather had been at the courthouse the day of George Stinney’s trial — and he’d seen the boy that morning. He’d watched George arrive in what he could best describe as ‘a cage.’ Police escorted the child inside, wearing chains so heavy he could barely walk, and an angry crowd spit on him as he passed. Yet, time and again, Sonya’s grandfather had said: I know that colored boy didn’t do it.” Sonya Eaddy-Williamson was related to the wealthy families that had controlled Alcolu in 1944, and her mother had gone to school with young Betty June.7 The people there who experienced his trial firsthand knew he was dealing with an injustice that nobody could fight, not even his lawyer, even if he did try. George’s trial lasted two hours. His attorney, Charles Plowden, did not call any witness to the stand nor present evidence that could help or cast doubt on the accusation against George.

Sonya recounted from going back to Alcolu, “Back in Alcolu, standing there, she didn’t only feel sorrow for the lives lost. She also felt confused. The old version of George’s crime didn’t make sense. How had no one in this small, segregated town noticed a young black boy bludgeon to death two white girls in broad daylight? How had nobody heard screams? And how did their bodies get several hundred yards away from where George had spoken to them, way off the road, with almost no blood or drag marks around them?”4 Not even George’s lawyer attempted to ask these questions or find evidence that could dismiss George. After the defense rested their case, the all-white jury stood and walked out to decide for George. After just ten minutes, they had returned with one.

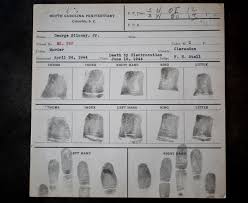

On April 24, 1944, George was sentenced to death by electric chair, with no mercy.

After his sentencing, George was moved to South Carolina Penitentiary, Columbia, South Carolina. There, he awaited his fate in the electric chair. There, his cellmate told what happened. “They also noted that a man named Wilford “Johnny” Hunter, who claimed to be Stinney’s cellmate, said that Stinney denied murdering Binnicker and Thames. “He said, ‘Johnny, I didn’t, didn’t do it,’” Hunter said. “He said, ‘Why would they kill me for something I didn’t do?’” 1 Soon, George would meet his fate three months later. The day was June 16, 1944; George and a few others lined up outside of the chamber, one after the other, to be executed. George was lined up, too. With a bible in hand, George waited in line to meet his fate. Just weighing 95 pounds and wearing an adult-size jumpsuit that was too big for him, George walked into the chamber and placed his bible on the bigger chair; the guard strapped him down, and they struggled too because of his size because the chair was too big and it was made to fit an adult. After strapping him down, they slipped the mask on his face, and the executioner asked if he had any last words. George said, “No, sir.” After that, officials turned on the switch and ran 2,400 volts of electricity through George’s small body. These waves caused the mask to slip down and expose George’s tear-streaked face and saliva dripping down from his mouth for the whole room to see. After just 10 seconds more, they shut it off, and George was shortly pronounced dead. “In just 83 days, the boy had been charged with murder, tried, convicted, and executed by the state.”1

After that, his case was left where it was, and George was buried in an unmarked grave, with scars lasting on his family. In Alcolu, the topic was laid to rest, and the community moved on and accepted that “justice had been served. But as time went on and as time changed, more and more started to talk about his case, from activists to historians, and by the early 2000s, George’s case was reopend and examined, and by 2014, 70 years later, after months of consideration, on December 17, 2014, Judge Carmen T. Mullen vacated the murder conviction, calling George Stinney Jr.’s death sentence a “great and fundamental injustice.” George Stinney Jr.’s siblings were overjoyed to learn that their brother was exonerated after 70 years, appreciating that they would live long enough to see it happen. “It was like a cloud just moved away,” said Stinney’s sister, Katherine Robinson. “When we got the news, we were sitting with friends… I raised my hands and said, ‘Thank you, Jesus!’ Someone had to be listening. It’s what we wanted for all these years.”3 George finally got justice, but it just leaves one thing unjust, and that is the girl’s murderers.

- Jaclyn Anglis, “The True Story of George Stinney Jr. And His Brutal Execution,” All That’s Interesting, February 26, 2024, ↵

- Death Penalty Information Center, “Remembering the Execution of 14-Year-Old George Stinney, 80 Years Later,” Death Penalty Information Center, September 25, 2024, ↵

- Jaclyn Anglis, “The True Story of George Stinney Jr. And His Brutal Execution,” All That’s Interesting, February 26, 2024. ↵

- Jennifer Hawes, “New Details Emerge About an Alternate Suspect in Alcolu Girls’ Murders,” Post and Courier, March 28, 2018. ↵

- Jaclyn Anglis, “The True Story of George Stinney Jr. And His Brutal Execution,” All That’s Interesting, February 26, 2024. ↵

- Equal Justice Initiative, “On Jun 16, 1944: Fourteen-Year-Old George Stinney Executed in South Carolina,” June 16, 2024. ↵

- Death Penalty Information Center, “Remembering the Execution of 14-Year-Old George Stinney, 80 Years Later,” Death Penalty Information Center, September 25, 2024. ↵

- Jennifer Hawes, “New Details Emerge About an Alternate Suspect in Alcolu Girls’ Murders,” Post and Courier, March 28, 2018. ↵

- Jaclyn Anglis, “The True Story of George Stinney Jr. And His Brutal Execution,” All That’s Interesting, February 26, 2024, ↵

- Jaclyn Anglis, “The True Story of George Stinney Jr. And His Brutal Execution,” All That’s Interesting, February 26, 2024, ↵

- Jaclyn Anglis, “The True Story of George Stinney Jr. And His Brutal Execution,” All That’s Interesting, February 26, 2024. ↵

6 comments

Alejandro Rubio Chappell

This was heartbreaking to read, especially knowing George Stinney was only 14. The way you described how quickly everything happened—arrest, trial, execution—made it even more disturbing. The fact that he had no real defense, no family around, and was buried in an unmarked grave says so much about the injustice. The quote from his sister at the end really stuck with me.

rmanzur

This article was deeply moving and shed light on a tragic and often overlooked part of history. The way it captured the injustice of George Stinney Jr.’s trial was both heartbreaking and powerful. It serves as an important reminder of the flaws in our justice system and the need for accountability. A truly compelling and necessary read.

TJ

I found the article’s detailed recounting of the Stinney case both tragic and illuminating. It reveals systemic racism at every stage, from the arrest of a 14 year old without family or counsel to the trial before an all white jury. The inclusion of firsthand accounts like the cellmate’s testimony and Sonya Eaddy Williamson’s memories really brought the injustice to life. Following the story through George’s 2014 exoneration provided a satisfying resolution while underscoring the long term impact on his family.

Meadow Ayala

This story broke my heart. Reading about what George Stinney went through as a scared 14-year-old boy with no protection, no real defense, and no chance at justice is devastating. It’s terrifying how easily an innocent life was destroyed just because of his skin color and the cruelty of the system at the time. Even though it took 70 years, I’m so glad George was finally exonerated. No child should ever suffer like he did. His story is a painful reminder of how important it is to keep fighting for justice, no matter how long it takes.

Martha Van Voorhis

What a great story to bring back for people to read and see how far we’ve come in the justice system. The system still needs improvements and fairness and I believe Micaella Sanchez will definitely make a difference! God be with her in her journey!

Catherine Sanchez

wow. Very insightful & beautifully written.