April 6, 2024

Hell Manifest: the 1st Marine Division in the Pacific War

The Southern Cross, or Crux, is a constellation of five stars in the shape of a cross, easily visible across the Southern Hemisphere; by late 1942, the men of the 1st Marine Division were desperately fighting tooth and nail to wrest control of a jungle island from the Japanese, as the stars of the Southern Cross shone above them. When their ordeal on the island finally ended, the insignia of the Division was designed as a blue diamond, with the Southern Cross; between the Cross was a large red “1”, with the name of the island down the middle; Guadalcanal. Guadalcanal would be the first step on a long march through hell that the 1st Marine Division underwent during the Second World War.

On August 7, 1942, the 1st Marine Division landed on Guadalcanal, an island in the south Pacific, initially facing little resistance. By the next day, the Marines had seized the island’s primary objective, the partially constructed airfield, finding it virtually abandoned.1 Unfortunately for the Marines ashore, their somewhat good fortunes (already marred by their own logistical problems), would come to a sharp and violent end that night, as a force of the Imperial Japanese Navy arrived and butchered the American and Australian ships off Guadalcanal, forcing the transports (with most of the Marines’ supplies) to abandon the men ashore.2 With the U.S. Navy struggling to break through the Japanese Navy, the Marines began to entrench in their position at the airfield, newly renamed “Henderson Field.” As they entrenched, Japanese aircraft began to hammer their position, taking advantage of the lack of U.S. carrier air coverage and the lack of aircraft at Henderson.3 Besides the lack of naval support, the first few days at Guadalcanal were comparatively lax, especially compared to what was to come. In the early morning of August 13, a recon patrol of 25 marines, led by Lt. Colonel Frank Goettge, an intelligence officer, departed to the west of the marine perimeter, as a Japanese prisoner had indicated that there may be a group of troops willing to surrender. Only three men from this patrol returned to friendly lines, saying that the patrol had been completely destroyed.4 Jim McEnery, a rifleman with the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, and his squad did stumble upon the patrol. Or rather, what was left of them.

The first thing I saw was the severed head of a Marine. I almost let out a yell because the head was moving back and forth in the water and looked like it was alive… The next thing I noticed was a leg that had been hacked off at the knee. It was still wearing its dead owner’s boondocker shoe with its laces neatly tied. A few feet away was a part of a bloody sleeve from a Marine first sergeant’s shirt with the chevrons still attached. Other chunks of rotting flesh that had once been human body parts were floating in the water and lying on the sand. The smell was overpowering… If I’d had something besides black coffee in my stomach, I probably would’ve been as sick as a dog.5

Besides some other expeditionary actions into the jungle and further entrenching, there was not much action; of course, with supply lines cut and provisions dwindling by the day, there was not much else that could be done. The Battle for Guadalcanal, for the first few months, would be a defensive one. And on August 20, the troops were called to the banks of the Tenaru River to defend Henderson Field against an incoming attack by the Japanese.

Our section – two squads, one with the Gentleman as gunner, the other with Chuckler as gunner and me as assistant – took up position approximately three hundred yards upstream from the sandspit. As we dug, we had it partially in view; that is, what would be called the enemy side of the sandspit… On our side, the west bank, was the extremity of the marine position; on the other, a no man’s land of coconuts through which an attack against us would have to pass.6

Such was the position that Robert Leckie, a U.S. Marine, and his section took up along the banks of the Tenaru.

During the night of August 21, the Japanese force led by one Colonel Ichiki, charged across the river in a full frontal assault in an attempt to break through with a mass charge, and the marine line opened up with a devastating fusillade which blunted the Japanese attack. The next morning U.S. light tanks began to advance, and by the evening, the attack had been repelled, with 777 Japanese troops dead, Colonel Ichiki among them. While not nearly the largest, or most intense engagement even at Guadalcanal, the Battle of the Tenaru let the Marines know that it was possible to face the Japanese and defeat them in battle. But it was also a sign of things to come in the Pacific; of the around 900 men that Ichiki had attacked with, only 15 of them were taken prisoner, with 12 of them wounded. When U.S. Navy corpsmen (medics attached to the Marines) tried to provide medical attention to some wounded Japanese, oftentimes they would, with their dying breaths, attempt to kill those helping them, with pistols or grenades.7

The slog at Guadalcanal would continue for months afterward, and it would set the precedent for the rest of the Pacific War:

There would be no quarter or glory here.

_________________________________________________

After a grueling, five-month-long campaign in the hostile jungles of Guadalcanal, the 1st Marine Division was withdrawn from the island, and sent elsewhere for recuperation and recovery; on December 8, Major General Alexander Vandergrift, commander of the 1st Marine Division, handed over command of the ground troops on Guadalcanal to Major General Alexander Patch.

By the end of the campaign, the men of the Division were in a poor state: their uniforms were splattered with mud and torn; the men themselves were dirty and exhausted, having fought for five months with barely any food and the realities of jungle life, namely sleeping in the rain and muck, among mosquitoes that carried malaria.

It was estimated that weight loss among them averaged around twenty pounds, and one regiment of the Division was found to have a third of its men unfit for combat.8 The Marines left the island the same way they came: by climbing cargo nets. McEnery recalled climbing up these nets:

When we climbed up the cargo nets to board the USS President Jackson and sail to Australia, many of us were so weak and exhausted we had to have help from the ship’s crew to make it to the top. Personally, I was so tired I wasn’t even embarrassed by it. I just thanked the swabbies for giving me a hand and looked for the nearest place to sit down.9

Similarly, one Corporal Charles J. Reed recalled that he was never able to eat white rice after Guadalcanal, due to it both being some of the only food available, and also due to said white rice being infested with maggots.

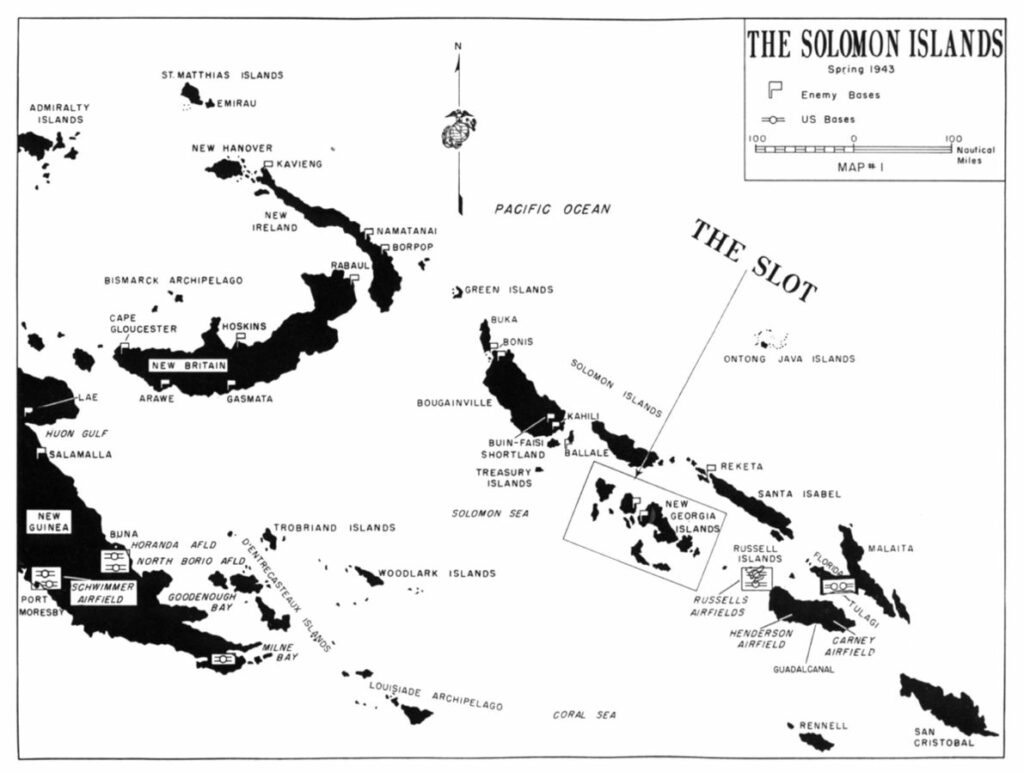

It was in Australia where the 1st Marine Division would be brought back up to strength, and their fighting capability restored. However, as the men of the Division rested and recovered, advances were being made by American and ANZAC troops. On the island of New Guinea, the Australian troops had managed to halt the advance of the Japanese throughout the island, in a prolonged and miserable campaign along the jungles and mountains of the Kokoda Track. With the two victories at Guadalcanal and New Guinea, the Japanese had effectively lost the initiative, and their momentum. The Allied drive up the Solomons and South Pacific had begun by mid-1943, and it aimed at isolating a major Japanese air and naval base at Rabaul, located at the north-eastern tip of the island of New Britain.10 In November of 1943, the 2nd Marine Division landed on Tarawa; during their landing, they faced a horrific barrage of mortar and small arms fire, and in three days had taken three thousand casualties. The Japanese force defending was destroyed with only a handful surrendering. This trend of opposed landings would continue throughout the American campaign in the Central Pacific, and the 1st Marine Division would eventually suffer through one of its own firestorms. But, for the next operation, they would be going back to the jungles of the Solomons.

_________________________________________________

For the Christmas of 1943, the 1st Marine Division was sitting off the coast of the island of New Britain, waiting to go ashore on the opposite end from Rabaul, with the aim of capturing another airfield to deny Japanese access to the passageway between New Guinea and New Britain. This place was known as Cape Gloucester. Or more aptly, Green Hell.

During the Second World War, the 1st Marine Division was comprised of three infantry regiments: the 1st Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Regiment, and 7th Marine Regiment. For ease of speaking during the war, each of these regiments was referred to by its number, with “Marines” tacked on; for example, the 1st Marine Regiment was referred to as the “1st Marines”, and “5th Marines”, and likewise. First ashore on Cape Gloucester was the 7th Marines, 3rd Battalion, with other elements of the 7th, 5th, and 1st Marines following soon after.

The landing was unopposed.

The elements of the Division that had landed on December 26 had managed to secure the airfield by the 31st.11 In accordance with their landing came the monsoon season. Compared to Guadalcanal, Cape Gloucester’s environment posed a larger threat than Japanese offensives; from the time the marines had landed, it rained nearly every day on Cape Gloucester, and the entire island was thick, nearly impenetrable jungle. Romus Burgin recalled mornings on Cape Gloucester:

At daybreak moisture was dripping off the leaves. Everything was soaked, and a kind of gray-blue mist hung in the air, a spooky mist that hid everything beyond the closest trees. It would be there almost every morning, especially after a rain. I never saw anything like it anywhere else and I never got used to it.12

With so much driving rain on Cape Gloucester, the troops ashore were apt to fall prey to the misery that abounded. Cases of malaria, dysentery, trench foot, and jungle rot proliferated. If it was any consolation, the Japanese were suffering just as much from the terrible terrain and weather as the U.S. Marines were; from a series of engagements, mostly Japanese charges towards entrenched Marines, such as on a place named Hill 660, onwards, most the Japanese encountered on the Marines’ drive to the east of the island were little more than isolated bands of emaciated stragglers.13

The dense jungle rotted away everything; from the cigarettes in one’s pocket to the very clothes on their back. Leckie recalls:

Perhaps I mean to say New Britain was evil, darkly and secretly evil… Nothing could stand against it: a letter from home had to be read and reread and memorized, for it fell apart in your pocket in less than a week; a pair of socks lasted no longer; a pack of cigarettes became sodden and worthless unless smoked that day; pocketknife blades rusted together; watches recorded the period of their own decay; rain made garbage of the food; pencils swelled and burst apart; fountain pens clogged and their points separated; rifle barrels turned blue with mold and had to be slung upside down to keep out the rain; bullets stuck together in the rifle magazines and machine-gunners had to go over their belts daily, extracting and oiling and reinserting the bullets to prevent them from sticking to the cloth loops – and everything lay damp and sodden and squashy to the touch, exuding that steady musty reek that is the jungle’s own, that individual odor of decay rising from vegetable life so luxuriant, growing so swiftly, that it seems to hasten to decomposition from the moment of birth.14

Much of the combat took place at very close quarters, due to the reduced visibility forced by the jungle; this meant that Marine patrols encountering Japanese stragglers were quickly involved in sharp, close, personal struggles, often necessitating inaccurate fire from the hip, and bayonets were often used.15 Infiltration was common on Cape Gloucester, and the Japanese employed a number of tactics to effectiveness. One of these included calling out to the Americans in good, well-spoken English, in order to lure individual soldiers into the darkness of the jungle and kill them.16

By February 3, 1944, the commander of the 1st Marine Division, Major General William Rupertus, confirmed that the Japanese were unable to launch further assaults against the airfield, and by the end of February, much of the West of the island was under uncontested American control. For the next month, the Marines pursued the remainder of the Japanese garrison through the jungle, and on April 9, 1944, the Japanese Major who was in charge of defending the airfield, Major Shinjiro Komori, was killed in a firefight with U.S. Marines. He was sick with malaria and only had three others with him, of whom two were killed. The last survivor was wounded and captured. On April 28, command on Cape Gloucester was turned over to the U.S. Army’s 40th Infantry Division, and the 1st Marine Division was finally able to leave the festering wound of Cape Gloucester.17

_________________________________________________

By the summer of 1944, the U.S. forces in the Pacific had made good progress in cutting through the extremities of Japan’s ring of islands that comprised their first layer of defense; in the Southwest, Allied troops had reached New Guinea, and in the Central Pacific, the Marianas Islands had been taken from the Japanese. The next phase of the drive towards the Japanese home islands would be to crush the inner ring of defense: the Philippines and Formosa (modern-day Taiwan), in order to sever Japan from the resources of South Asia.18

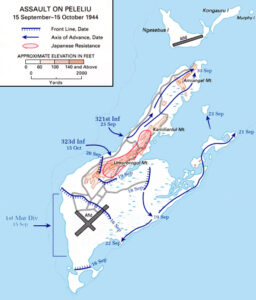

The next assault that the 1st Marine Division would participate in would be at a small island around 500 miles to the east of the Philippines; Peleliu. Part of the Palau Islands, General Douglas Macarthur wanted this island secured, and its airfield neutralized, in order to protect his approach to the Philippines. The Japanese had held Peleliu since the First World War, when the island was seized from the German Empire, and in twenty years’ time, they had ample ability to construct fortifications among Peleliu’s many rocky crags and valleys. After an American air raid that effectively ended the threat to the airfield in late March, the Japanese 14th Infantry Division was transferred from Manchuria to Peleliu, led by Lieutenant General Sadae Inoue. This division, one of the oldest in the Japanese Army, was comprised of 11,000 battle-hardened troops that had spent years in China and Manchuria. Upon their arrival in April 1944, they began entrenching further and constructing a labyrinthine network of mutually supporting fields of fire and fortifications. There would be no more senseless Banzai charges. Instead, the Japanese had one goal at Peleliu: draw out the conflict as long as possible, until either the Americans were repelled, or all 11,000 men of the 14th were dead. 19

Here, everyone would bleed.

_________________________________________________

The morning of September 15, 1944, the 1st Marine Division began their assault on Peleliu, having been told by General Rupertus that the battle would be short; three days long, maybe four. Upon embarking aboard their landing craft, LVTs and a handful of LVCPs and DUKWs, the Marines observed that the entirety of their beachhead was obscured by a thick cloud of black smoke. For the past few days, the U.S. Navy had been bombarding Peleliu from the air and from the sea; on the day of the assault, 1,400 tons of explosives were fired from battleships and cruisers offshore onto the island, which was only five miles long and two miles wide.20 Such a bombardment had rendered nigh every tree stripped and blackened and left a rocky wasteland, and the U.S. Navy reported that all targets that were deemed worth shelling were destroyed. On the northernmost beach, White Beach 1 and 2, the 1st Marines landed; on the center beach, Orange Beach 1 and 2, the 5th Marines landed. On the southernmost beach, the 7th Marines landed.

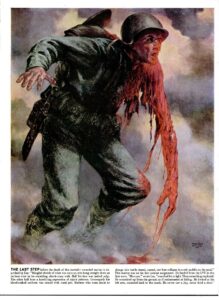

Immediately after entering range, the marines, vulnerable in their craft as they headed into a firestorm, were battered with extremely heavy mortar, machinegun, and artillery rounds as their LVT’s crawled towards the beach, at a painstakingly slow 7 knots. When the LVTs and other craft caught the beach, ramps slammed down, men ran out, (the unlucky ones, in LVTs without ramps, had to jump over the side), and immediately ran forward and dove in the sand, as war artist Tom Lea, of El Paso, TX, described, “huddled like wet rats in death.”21 Tom Lea would later paint a number of pieces of what he saw at Peleliu, some of the most famous of them being “The Price” and “Thousand Yard Stare.” Late in the afternoon, a well-coordinated Japanese counterattack, tanks supported by infantry, was repelled. By the end of the first day at Peleliu, the 1st Marine Division had taken over 1,000 casualties.

The next thrust was to come the following day: the 5th Marines would rush across the airfield, a vast open expanse devoid of cover apart from a few shell craters; the 7th Marines would advance further into the south of the island, and the 1st Marines would continue to doggedly assault the Japanese fortifications within the Umurbrogol Mountains, or what would become known as “Bloody Nose Ridge.” The 5th Marines managed to make a mad dash across the airfield, taking mortar and artillery fire from the Ridges that dominated the entire island. The 7th Marines were making some progress in securing the southern portion of the island. The 1st Marines were stonewalled. In just over a week of fighting, the 1st Marine Regiment had lost its fighting capability. When they were finally pulled off the line, the 1st Marines had taken 56% casualties overall; their 1st Battalion had lost 71% of its men. They were relieved by the Army’s 321st Infantry Regiment, while the two other Marine regiments closed in on Bloody Nose Ridge. The original prediction of a quick but rough fight was turning out to be terribly false.22

Characteristic of Peleliu was the disturbing atmosphere the island cultivated. Part of this was Japanese infiltrators. At night, individuals or small groups of Japanese soldiers would creep from the caves on the island and attempt to sneak into the foxholes of Marines to kill them while they slept. As no one was allowed to sleep in a foxhole alone, there was usually a violent, close struggle as Marine and Japanese scuffled in the dark with hands, knives, bayonets, rifle butts, and jagged rocks. During the day, temperatures regularly reached over 110 degrees Fahrenheit. When the wounded were attempting to be evacuated, already a challenge often requiring four men due to the sharp crags and valleys of Peleliu, Japanese snipers would deliberately aim at the stretcher-bearers. 23

The unique geography of Peleliu, being an island of coral rock, made it not only impossible to dig in with entrenching tools, but also created an environment that was often described as more akin to fighting on the moon, or Mars. Eugene Sledge wrote of Peleliu:

Those though, were typical modern battlefields. They were nothing like the crazy-contoured coral ridges and rubble filled canyons of the Umurborgol Pocket on Peleliu. Particularly at night by the light of flares or on a cloudy day, it was like no other battlefield described on earth. It was an alien, unearthly, surrealistic nightmare like the surface of another planet.24

Prolonged fighting in the ridges seemed to devolve the men there, turning the Japanese and Americans from human beings to something more like two emaciated, filthy, savage dogs biting, clawing, and scratching over a small scrap of meat. McEnery, now a rifleman who had survived Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester, described the situation on Peleliu:

We attacked the underground Jap [sic] strongholds in the Umurborgol Pocket and slaughtered their occupants by every means available. We incinerated them with flame-throwers. We blasted them to bits with artillery rounds fired directly into their caves. We poured grenades by the hundreds into their bunkers and pillboxes. Our planes seared them with napalm from the air. We called in bulldozers and demolition squads armed with TNT to bury them alive… And of course, we shot them and bayoneted them and cut their throats and strangled them with our bare hands when they came at us as infiltrators in the night. We gouged their eyes out and pounded their skulls to mush with rocks. We jerked them up and threw them off cliffs. 25

After thirty days of constant slaughter among the shattered rocks of Peleliu, the last remaining regiment of the 1st Marine Division, the 5th Marines, was pulled off the line on October 15, 1944, and over the course of the next few days, they were shipped back to the island of Pavuvu, their temporary home since after Cape Gloucester, and they were replaced by the rest of the Army’s 81st Infantry Division. In a month, the 1st Marine Division sustained 6,786 casualties, and was combat ineffective until the Battle of Okinawa. They would carry the memories of Peleliu for the rest of their lives.26

The battle for Peleliu would continue until November when the island was finally declared secure. Of all the battles of the Pacific island hopping campaign, Peleliu had the highest casualty rate of any of them: of all the American forces that set foot on the island during the battle, a whopping 40% would become casualties. The ratio of Japanese to American casualties was close to 1:1.27 Despite being described by many Marine commanders and enlisted as one of, if not the toughest battle of the entire Pacific War,28 Peleliu remained unknown to many, even to the modern day; perhaps the most widely known facet of Peleliu among the general public is a painting: Tom Lea painted “That 2,000 Yard Stare” from his experiences on Peleliu; the term “thousand yard stare” was thus popularized as a result of the struggle for Peleliu.29

_________________________________________________

By mid-1945, the U.S. was advancing closer and closer to the Japanese Home Islands; in a month-long, hard-fought campaign, the island of Iwo Jima was secured. Being the first of the Japanese homeland to be invaded, it was tenaciously defended at a large cost to both sides; the garrison was almost entirely destroyed, having fought to the death, and the Marines and Army troops suffered over 20,000 casualties. The next target for the U.S. was the island of Okinawa, part of the Ryukyu Islands, only 330 miles from the Japanese Home Islands; and as the U.S. got closer and closer to the Home Islands, the cost of each campaign climbed higher, and the troops allocated kept growing.

For the invasion of Okinawa, the ground force comprised 183,000 combat troops with 120,000 support troops. The logistics alone required 1,200 ships to maintain both the invasion force and ~200 American and British warships intended to support them, all over 6,000 miles from the mainland United States.30

The invasion of Okinawa was intended to provide a stepping stone for the next operation the Americans were slated to undertake at the end of the year: Operation Downfall. The invasion of Japan.

What would be seen on Okinawa would beg the question:

If an invasion of an island only 60 miles long could cost so many lives, what would it take to invade Japan itself?

_________________________________________________

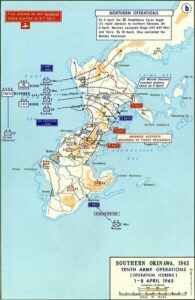

The landing on Okinawa was, for the most part, unopposed, in stark contrast to nearly every other battle since Tarawa. The 1st Marine Division crossed the island and then turned north, encountering little resistance. Instead, they encountered a large civilian population, and the Marines and Okinawans, mostly peasant farmers, warmed to each other. Unfortunately, this peaceful environment of the north was not to last.

In the south, the Army was blocked by a formidable obstacle; Shuri Ridge. The Japanese had extensively fortified the Shuri ridges, and the U.S. forces were unable to attain any ground for weeks. This and the seasonal rains ended up turning the environment into a mucky, stagnated front line permeated by death and corpses all around; Japanese and American. The situation was more akin to the trench warfare of the First World War than an island campaign. On May 8, Victory in Europe was announced, and was greeted with ambivalence by the Marines; they were still stuck in a horrific deadlock, unable to break Japanese lines and unable to flank from the sea. They were stuck in a cesspool. Weapons rusted. Craters and foxholes filled. Bodies rotted, unable to be moved from where they lay.31

Sledge recalled the effect Shuri had upon the Marines there:

The combat fatigue cases were distressing. They ranged in their reactions from a state of dull detachment seemingly unaware of their surroundings, to quiet sobbing, or all the way to wild screaming and shouting. Stress was the essential factor we had to cope with in combat, under small arms fire, and in warding off infiltrators and raiders during sleepless, rainy nights for prolonged periods; but being shelled so frequently during the prolonged Shuri stalemate seemed to increase the strain beyond that which many otherwise stable and hardened Marines could endure without mental or physical collapse.32

By late May, however, the 6th Marine Division had been hammering a hill critical to the integrity of the Shuri ridges, and on May 26, they had finally broken through. The first chink in the armor of Shuri had been breached; the U.S. Army and U.S. Marines began to envelop the main stronghold in a devastating pincer movement. The 1st Marine Division seized this opportunity alongside their brethren units, and on May 29, 1945, the 1st Marine Division seized Shuri Castle. Upon it they raised the same U.S. flag that had been flown over Guadalcanal, Cape Gloucester, and Peleliu.33

By the end of Okinawa, 49,151 American casualties had been taken as a result of combat; with 26,000 as a result of non-combat causes, like disease and “combat fatigue”; the precursor term for PTSD. The Japanese suffered 90,000 troops killed, and 11,000 captured. Outnumbered 2:1 in sheer numbers, and more in terms of firepower, the Japanese defenders had managed to hold out from April to June. Just as disturbingly, 140,000 Okinawan civilians were caught in the crossfire, many of them having taken their lives in suicide as a result of Japanese propaganda.34 The 1st Marine Division would spend the next few months preparing for the eventuality of an invasion of the Japanese Home Islands, an invasion that thankfully never came. Sledge recalls these final few apprehensive days:

Ugly rumors circulated that we would hit Japan next, with an expected casualty figure of one million Americans. No one wanted to talk about that… On 8 August we heard that the first atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan. Reports abounded for a week about a possible surrender. Then on 15 August 1945 the war ended. We received the news with quiet disbelief coupled with an indescribable sense of relief. We thought the Japanese would never surrender. Many refused to believe it. Sitting in stunned silence, we remembered our dead. So many dead. So many maimed. So many bright futures consigned to the ashes of the past. So many dreams lost in the madness that had engulfed us. Except for a few widely scattered shouts of joy, the survivors of the abyss sat hollow-eyed and silent, trying to comprehend a world without war.35

With the end of Okinawa and the war, the 1st Marine Division had finally emerged on the other side of their journey through the depths of hell manifest.

They could finally go home.

- Frank O. (Frank Olney). Hough et al., Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, v. 1 (Washington: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958), 254-257. ↵

- Frank O. (Frank Olney). Hough et al., Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, v. 1 (Washington: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958), 257-262. ↵

- Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, 1st ed (New York: Random House, 1990), 128-129. ↵

- Frank O. (Frank Olney). Hough et al., Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, v. 1 (Washington: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958), 281-283. ↵

- Jim McEnery and Bill Sloan, Hell in the Pacific: A Marine Rifleman’s Journey from Guadalcanal to Peleliu, First Simon&Schuster hardcover edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 66-67. ↵

- Robert Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow: From Parris Island to the Pacific (Arcadia Press, 2018), 65. ↵

- Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, 1st ed (New York: Random House, 1990), 150-157. ↵

- Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, 1st ed (New York: Random House, 1990), 521-522. ↵

- Jim McEnery and Bill Sloan, Hell in the Pacific: A Marine Rifleman’s Journey from Guadalcanal to Peleliu, First Simon&Schuster hardcover edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 137. ↵

- Henry I. Jr Shaw and United States. Office of Naval History., Isolation of Rabaul, (United States. Marine Corps.) History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, v. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1963), 8-11. ↵

- Alan Rems, South Pacific Cauldron: World War II’s Great Forgotten Battlegrounds (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014), 156-157. ↵

- Bill Marvel and R. V. Burgin, Islands of the Damned: A Marine at War in the Pacific (New York: New American Library, 2014), 73. ↵

- Alan Rems, South Pacific Cauldron: World War II’s Great Forgotten Battlegrounds (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014), 157-160. ↵

- Robert Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow: From Parris Island to the Pacific (Arcadia Press, 2018), 201-202. ↵

- Jim McEnery and Bill Sloan, Hell in the Pacific: A Marine Rifleman’s Journey from Guadalcanal to Peleliu, First Simon&Schuster hardcover edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 165. ↵

- Jim McEnery and Bill Sloan, Hell in the Pacific: A Marine Rifleman’s Journey from Guadalcanal to Peleliu, First Simon&Schuster hardcover edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 163. ↵

- Henry I. Jr Shaw and United States. Office of Naval History., Isolation of Rabaul, (United States. Marine Corps.) History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, v. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1963), 427-430. ↵

- George W. Garand, Truman R. Strobridge, and United States. Marine Corps., Western Pacific Operations, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, v. 4 (Washington, D.C.: Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1971), 51-52. ↵

- George W. Garand, Truman R. Strobridge, and United States. Marine Corps., Western Pacific Operations, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, v. 4 (Washington, D.C.: Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1971), 54, 66-74. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 130-134. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 135-138. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 140-149. ↵

- E. B. Sledge, With the Old Breed (Random House Publishing Group, 2008), 128-129. ↵

- E. B. Sledge, With the Old Breed (Random House Publishing Group, 2008), 145. ↵

- Jim McEnery and Bill Sloan, Hell in the Pacific: A Marine Rifleman’s Journey from Guadalcanal to Peleliu, First Simon&Schuster hardcover edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 235. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 156-157. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 158-159. ↵

- George W. Garand, Truman R. Strobridge, and United States. Marine Corps., Western Pacific Operations, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, v. 4 (Washington, D.C.: Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1971), 285-286. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 150-151. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 563-564. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 604-620. ↵

- E. B. Sledge, With the Old Breed (Random House Publishing Group, 2008), 266. ↵

- E. B. Sledge, With the Old Breed (Random House Publishing Group, 2008), 277. ↵

- Ian W. Toll, Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, First edition (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020), 639-640. ↵

- E. B. Sledge, With the Old Breed (Random House Publishing Group, 2008), 317. ↵

Tags from the story

1st Marine Division

American History

History

Nomination-American-Studies

Nomination-Journalistic-Explanatory

Pacific Theatre

Pacific War

Joseph Reed

Joseph is an undergraduate History and Political Science student of the St. Mary’s Class of 2026. He enjoys reading, studying history, and writing stories.

Author Portfolio PageRecent Comments

qmero

There cannot be a better description of the Pacific campaign of World War Two than how you’ve described it in your title, Hell Manifest. Your description of the strife encountered by troops not only in battle with the Japanese but also in the struggle for survival on the very islands they fought in could be described in no lesser terms. Thank you for telling such an important story!

23/04/2024

8:31 am

Vianna Villarreal

What a great and interesting topic to write about. Very great way to emphasize the horrors of war time and the soldiers who are involved during these times. It is a time of full suspense where men may never see their families again. While also having to endure physical conditions along with mental obstacles. There are so many men who were effected during these times who never got out of it mentally. Such an interesting way to speak about war time and the horrors that were made to endure.

24/04/2024

8:31 am

dandrews2

Hi Joesph, I really enjoyed reading your article about the 1st Marine Division in the Pacific during World War II. Right away, the title“Hell Manifest: the 1st Marine Division in the Pacific War” got my attention and made me want to read this article. You did a great job delving into the experiences the Marines had endeavored while looking at the war from the Japanese perspective which I really liked. As someone who enjoys learning about military history, this was a good read and I thank you for this.

26/04/2024

8:31 am

jhollowell

This article provides such a broad, yet in-depth understanding to the reader, as it has maps, vivid descriptions of the battlefields and conditions faced by the Marines, and gives first-hand accounts that show the reality of the challenges they faced. I enjoyed that the author touched on all kinds of specifics like combat tactics and specific focus on the individual battles. The last line of the article was super powerful.

26/04/2024

8:31 am

lramirez46

Hello Joesph! After reading your article it certainly did an excellent job in describing what the Marines went through in the Pacific. You did a good job of describing the conditions that Marines were facing but you also give a little bit of perspective to the Japanese which is not often done. Along with that, you do an amazing job when it comes to telling the story of the 1st Marine Division and the challenges they faced while they were battling the Japanese in the Pacific.

21/04/2024

8:31 am