The late afternoon heat buzzed in waves across Oklahoma, passing over a Chickasaw County farmer by the name of “Bateman,” steering a workhorse through fields of colorful crops including endless rows of corn, oats, milo maize, and golden potatoes. Bateman’s dawn-to-dusk chores were soon to be coming to a close on his serene pasture, when a crack of sound ran into the field. Suddenly, gunfire began to whiz past Bateman and into the neat lines of the crops. The plow suddenly jolted as Bateman’s horse reacted harshly, snapping off the machine and fleeing into the horizon. Consequently, this sent the carriage crashing forward as Bateman flew off his plow face first into the orange Oklahoma dirt. Fulfilling his fear, Bateman’s eyes slowly rose up and interlocked with his murderer, a Seminole Indian by the name “Greenleaf.” Known for his brutality, thievery, and countless kills of members of his own tribe, Bateman quivered with fear as he was robbed of his belongings and fatally shot in the middle of his field.1

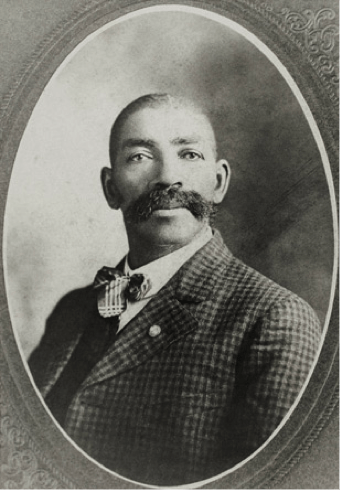

Once news reached the town of the brutal murder, farmers and families feared for their own lives. Fortunately, a sharp deputy marshall was passing through the county after finishing up a job in Little Rock, Arkansas. He was a living legend, a man credited with arresting more than 3,000 felons for some of the deadliest crimes in the wild west, and just the mentioning of his name could make a thief get the chills. He was Bass Reeves, the deputy marshall who Greenleaf had unknowingly ushered into Chickasaw County.2

In order to grasp the gravity of Greenleaf’s encounter with Bass Reeves, to fully explain the cold, hard hand of justice that was about to slam down in Chickasaw County, we must return almost four decades prior, to a hot July in 1838, in the small town of Crawford County, Arkansas. Born to a black family in the south, Bass Reeves was born a slave, given the name of Bass by his birth parents followed by the surname Reeves, for the family who owned Bass’s family. In his early life, Bass did not have a childhood per se, but instead spent long days trudging along beside his parents as a water boy on the hot Arkansas plantation. As Bass grew taller, so did his chores, meaning that he was recruited fairly quickly as a field hand by the age of eight.

Soon after, the Reeves family moved to northern Texas, just across the border from the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations. These Indian Territories had formed from large-scale capturings of Native American lands for the profit of selling of them to Americans looking to move westward. As Bass grew of age, he was given the tasks of tending to the mules and horses owned by his master’s family. Little did he know this would lead to his becoming the blacksmith’s helper. Bass was swift with his work, being young and eager to take on additional duties as well. Bass soon gained recognition among the Reeve’s slaves for his work and was selected as his master’s head “companion,” a position of prestige among his fellow slaves, and it meant that Bass spent far more time inside with the Reeves family and less time doing manual field labor.3 Bass accompanied his master nearly everywhere, serving as valet, bodyguard, coachman, and butler. During this time, Bass was taught how to handle a gun, originally for precautionary measures. But as a young man, Reeves’ mastery of the weapon impressed most adults. His master decided to showcase Bass’ talent and eventually entered him in local turkey shoots and competitions that included both white and black competitors.4

Reeves’ master was better known by his Civil War title, Colonel George Robertson Reeves, and was a member of the Eleventh Texas Cavalry. He brought Bass along into every treacherous battle. The hardships of war crafted Bass into an astounding young man. It was during this time that young Reeves gained combat skills, mastered precision shooting, and knowledge of battlefield tactics. The sight of blood and death at such an early age had no doubt hardened Bass into a painful perspective on society, although Bass soon realized that his newly gained talents were not something he wanted to waste. Given his great exposure to violence at a young age, Bass soon discovered he could use his battlefield knowledge for something good in the world. Just a county away from northern Texas, the Northern Cherokee Nation was not only a home for Indians fleeing violence, but it was also a hideout for runaway fugitive slaves.5 The average person feared Indians as head-scalping savages, and fugitive slaves had been demonized during this time period as dangerous criminals.

Therefore, areas of Indian territory were home to abolitionists and Indians who were able to escape into territories free from white men who feared these areas far too much to dare to enter them.6 Bass Reeves ran away to the Northern Cherokee Nation, becoming a fugitive slave. He immediately befriended Chief Opotheyahola, who led abolitionist movements against the south and organized a cavalry brigade against the south during the Civil War. The chief advised Bass to stay in the northern territory of the Cherokee Nation and fight alongside his men. It was here that Reeves learned how to communicate with different tribes and rode into battle alongside Chief Opotheyahola and his men.7 Reeves eventually left the war to start a family, packing what he had and traveling to Arkansas.

Despite moving for the sake of settling down, it did not take long before Reeves began offering his assistance to the U.S. law enforcement stationed in Fort Smith, Arkansas for the first time. Offering his in-depth knowledge of the Indian Territory, along with his impeccable tracking skills, Reeves impressed many officers, which is what led to his recommendation for a U.S. deputy marshal position. In 1875, Reeves was among two-hundred U.S. deputy marshals sworn in by Judge Isaac C. Parker, appointed that year to preside over the 74,000-square-mile Western District of Arkansas.

Based in Fort Smith, Arkansas, the district included the entire Indian Territory, which had become a notorious hiding ground for outlaws. Any non-Native American who committed a crime was to be tried in the Western District. U.S. Marshal James Fagan recruited the 38-year-old Reeves because of his knowledge of Native American lands and languages, and because Native Americans were often scared of white men, given that many roaming their lands were criminals. The court at Fort Smith ran nonstop in the fight against the lawless. Between May 10, 1875, and September 1, 1896, Judge Parker tried 13,490 criminal cases and won better than 8,500 convictions.8

marshals of Judge Parker’s court (1875) | Courtesy of North Texas E-News

Fast forward to Greenleaf’s escalating activities, and we find a case that would involve one of the wild west’s most notorious criminals, who performed countless heinous murders and robberies throughout Chickasaw County. Following the Bateman murder in Chickasaw, Reeves was enlisted to capture Greenleaf, although to the town’s and Reeves’s disappointment, only a few days passed before the notorious Seminole Indian outlaw Greenleaf murdered and robbed a mail rider near Old Fort Washita on July 3, 1881, just days after Bass Reeves swore out a warrant for the arrest of Greenleaf on July 1, 1881.9

The hunt for this Indian outlaw lasted almost a decade, and every day that Greenleaf evaded the law, Reeves’ blood boiled.10 All of this time, Greenleaf’s business had been whiskey peddling, and every marshal that had traveled through Seminole, Creek, and Chickasaw country carried warrants for him. Greenleaf was a vicious killer, as the Arkansas Gazette described. He put twenty-four bullets in one of his victim’s body.

Time passed, as it became impossible to organize a task force for hunting Greenleaf. It became known that do to so would result in sure death, unless the hunt was successful. Reeves was in Chickasaw County at the time, and had caught news of Greenleaf’s arrival into the county with a load of whiskey. The sun was falling in the west as Reeves arrived on the site of Greenleaf’s camp. Reeves wartime intuition led him to believe the best time to raid the site would be between when everyone had gone to sleep for the night until near daylight, and then move up close to the house. Just as the dawn rose, he and his posse charged the shelter, jumped the fence, and before Greenleaf could even sit up in bed, he was met face to face with an array of guns. Alas, no other choice, Greenleaf surrendered after almost a decade of being a menace to society. Following his capture, townspeople spread the news like wildfire, even earning Reeves statewide recognition after the story was published in the prestigious Arkansas Gazette.11 Many citizens had lost hope of Greenleaf ever being brought to justice, and doubted it could be true. Surprisingly, hundreds flocked to see that it was really so, some riding as far as eighteen miles to convince themselves of Greenleaf’s capture.12

We typically picture the old wild west based on what is brought to life in movies, as gun-slinging cowboys that fight crime, lassoing wild stallions, and gallantly riding off into the sunset with their fair maidens, but did it ever occur to anyone that Hollywood might have gotten something wrong in their blockbuster films? Although Bass Reeves will retain his fame for his work serving this country as a deputy marshal, whether he would have captured Greenleaf or not, Reeves was famous for his extensive service to this country. But in many famous depictions of lawmen of the west, we are painted a picture of this lawman Reeves as a white man. The Lone Ranger serves as an example of how somewhere in the saloon fighting and rattlesnake tussling, the iconic Lone Star Ranger’s racial identity got switched from the black Reeves to simply a white man. Historians have pointed out how Bass Reeves, much like the Lone Ranger, traveled with a Native American buddy that he had befriended in Chickasaw, and with whom he had helped navigate throughout the West. Surprisingly, amid the racial tensions in the southern states, black men found freedom in escaping to the wild west, providing for themselves through dangerous work capturing criminals in hopes of starting a new life, and we explicitly see this in the case of Bass Reeves.13

A 25-foot work of art honors the lawman in downtown Fort Smith, Arkansas, believed to be the first black U.S. deputy marshal west of the Mississippi, yet the iconic image of “the sheriff in town” will be illustriously framed in history as a white lawman, despite the historical evidence pointing to an African American lawman that sought freedom and justice in the treacherous Wild West, while performing work alongside Native American comrades.14 More importantly, Bass Reeves will be remembered for his persistence in the face of adversity, gallantry in the face of evil, and as a remarkable sportsman.

- Nudie E. Williams, “Bass Reeves: Lawman in the Western Ozarks,” Negro History Bulletin 42, No.2, (1979): 26-27. ↵

- The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, May 2012, s.v., “Bass Reeves 1838-1910,” by Art T. Burton. ↵

- Roger Rouland, Bass Reeves 1838-1910 (Detroit: Gale, 2012), 120. ↵

- Nudie E. Williams, “Bass Reeves: Lawman in the Western Ozarks,” Negro History Bulletin 42, No.2, (1979): 38. ↵

- Gary Paulsen, The Legend of Bass Reeves (New York: Laurel Leafs, 2006), 34. ↵

- Roger Rouland, Bass Reeves 1838-1910 (Detroit: Gale, 2012), 121. ↵

- Nudie E. Williams, “Bass Reeves: Lawman in the Western Ozarks,” Negro History Bulletin 42, No.2, (1979): 37. ↵

- The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, May 2012, s.v., “Bass Reeves 1838-1910,” by Art T. Burton. ↵

- “He’s a Bad Indian,” Arkansas Gazette, April 29, 1890, 7. ↵

- Nudie E. Williams, “Bass Reeves: Lawman in the Western Ozarks,” Negro History Bulletin 42, No.2, (1979): 37. ↵

- “He’s a Bad Indian,” Arkansas Gazette, April 29, 1890, 7. ↵

- Gary Paulsen, The Legend of Bass Reeves (New York: Laurel Leafs, 2006), 34. ↵

- Nudie E. Williams, “Bass Reeves: Lawman in the Western Ozarks,” Negro History Bulletin 42, No.2, (1979): 38. ↵

- The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, May 2012, s.v. “Bass Reeves 1838-1910,” by Art T. Burton. ↵

27 comments

Auroara-Juhl Nikkels

I had not heard of Bass Reeves before reading your article. Your introduction really caught my attention. Your article really was a story, with many smaller but equally as important stories in it. You did a really good job with the flashbacks and helping the reader understand the importance of every little and last detail you put into the story.

Maricela Guerra

This article was very informative, yet at the same time not too boring. The author did well telling the story of Reeves giving out credible information. Overall this article was well conducted and very entertaining. I didn’t know that Reeves was such a hero to all. This story was also very westerny and that was a cool approach that I haven’t seen yet. Well done on the author’s part.

Jasmine Jaramillo

I enjoyed reading this article I didn’t know about Bass Reeves until I read this article. I learned a lot about his life growing up as well as the early history in the west. I didn’t know that there was so much crime and criminals were around back in the day. I also thought it was pretty progressive how Reeves was able to become a deputy marshal. Reeves was able to learn a lot of skills as he was growing up that helped him to earn jobs and impress people who might not have given him the opportunities.

Erin Vento

I think there were a lot of interesting facts in this article that don’t get talked about or swept under the rug. I never knew that some slaves would hide out with Indian tribes for safety, and I didn’t know that the Lone Ranger was based off someone real- let alone to find out that they portray him a white man. Bass Reeves has probably the most interesting life life I’ve ever read about, and I can totally see how he would be a person of interest for Hollywood, but I wish that they hadn’t tried to hide who he really was.

Destiny Leonard

This article shows how throughout history there has been a stigma regarding race and how within history the lighter complexion you were the lighter you were the better it would be. within the article it alludes to the possibility that the lone ranger was based on Bass Reeves yet the character was white washed. Unfortunately this still happens today. overall great article.

Jose Figueroa

I was really caught off gaurd by your cover picture and it was an African American cowboy, something we often do not see. At the end of the article, you did a great transition in going from the storytelling aspect to the cultural significance of him. He was a great deputy and should be remembered as such. The flash back towards the beginning was also excellently done!

Isaac Saenz

This article does a very nice job of enticing the reader from the beginning to keep on reading. The hook involving the murder of the unfortunate farmer was vivid and the background information of both the protagonist and antagonist of the story was well written and informative. I would have liked the climax of the story to have been more detailed and exciting but overall a great story about crime and justice in the Wild West.

Kayla Lopez

From the very first sentence, this article captured my full attention. I had no prior knowledge on Bass Reeves and all the incredible things he accomplished in his lifetime. It was fascinating to know that when he was younger he was a slave and that he ran away in order to be something more; which he surely accomplished. The was so much information and it was all organized very well.

Iris Henderson

The remarkable story of Deputy Marshall Bass Reeves was one that I will not forget. The story was beautifully written, captivating, and paired with great imagery. Reeves has a really interesting life, from growing up in slavery to escaping slavery and then to becoming a marshall and all of the details in between! I sincerely hope that they make a movie about him if they haven’t already because I love film and this would be an amazing story to tell.

Raymond Davila

This article was interesting and informative. In the way that now after reading this article it makes sense as to why there never any heroic or famous black men in early western movies, or an early hollywood movies to begin with. Especially like how the article says that during the time Bass was alive the west was very violent and lawless after the civil war. So why would a well off white man go to such a place and do such dangerous work when he had plenty of other possible work opportunities.