Many of us know that the Spanish conquest of Latin America brought tremendous change to those regions. In Mexico specifically, Spanish conquest ended one of the most powerful and developed empires in Latin America, which was the Aztec empire. This led to many changes and one of them was the effects the Spanish language had on the Nahuatl language.

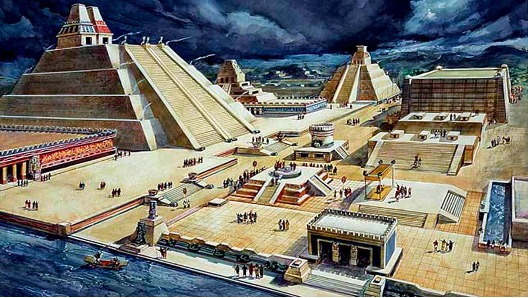

In the year 1521 the Aztec empire fell due to Spanish colonization. Hernán Cortés, the Spaniard in charge of the expedition to Mexico, and his men captured and killed the Aztec emperor Montezuma II, due to Montezuma II’s uncertainty on how to react to the Spaniards. The emperor believed Cortés was an Aztec god who was prophesied to bring universal peace to the Aztec empire. After his death, Montezuma II was replaced by his brother Cuitlahuac, whose leadership pushed away Cortés and his people. Cuitlahuac later died of smallpox, which also killed much of the Aztec population. This, in fact, led the empire to its weakest point and, with, the help of neighboring tribes including the Texcocans, Chalca, and Tepanec, Cortés placed Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital under a three-month siege. He accomplished defeating the strong and resistant Aztec empire after his many earlier failed attempts to do so.1

The history of Nahuatl is fascinating, yet complicated. The term “Nahuatl” literally means “something that sounds good and clear”. Classical Nahuatl was the administrative language of the Aztec empire that served as a lingua franca in Central America from the 7th to the 16th century AD, when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the New World. Nahuatl speakers, or the Nahua people, are thought to have originated in what is now the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico.2 It is believed that the Nahua split from other Uto-Aztecans, who were people who spoke any of the languages that belong to the Uto-Aztecan language family, such as Comanche, Hopi, Nahuatl, Paiute, Pima, and Shoshone.3After this split, around 500 AD, the Nahua migrated to the central part of Mexico, eventually spreading throughout Mexico.4 Nahuatl served as the language for the Toltec empire, a powerful empire founded by the Nahua that ruled the central part of Mexico from the 10th to mid-12th centuries AD. After its fall, Nahuatl served as language for the Aztec empire, which dominated Mexico from 1325 to 1521.5

Nahuatl was known for its use of a “tl” sound as a single consonant. This sound, /ɬ/, the alveolar lateral affricate, was pronounced by placing the tongue in the position to pronounce the letter “t,” while pushing air out from both sides of the tongue.6 Nahuatl phonology was also known for the glottal stop, an interruption on the airstream by closing the glottis (the space between the vocal cords), which causes the vocal cords to stop vibrating. Upon release, there is a slight choke, or cough like explosive sound.7 Classical Nahuatl used a set of 15 consonants and four long and short vowels. It was also considered to have agglutinative grammar, in that it used prefixes and suffixes, compound words, and it doubled syllables. Nahuatl added different affixes, prefixes, and/or suffixes to roots to form long words. Then the words as a whole functioned as a sentence does in English.8

The Spanish colonization of Mexico brought many changes to the already well-structured and developed civilization. Tenochtitlán itself was rebuilt into a Spanish-style capital city, which they called La Cuidad de México (Mexico City).9 Two of the main reasons why Spanish conquistadors arrived in Mexico in the first place was to look for gold10 and to convert the natives to Christianity.11 After the defeat of the Aztec empire and thus, the vast majority of the population of Mexico, the Spaniards took on the mission of achieving these initial goals.

At first Spanish conquistadors tried to persuade natives to learn Spanish, after converting them to Christianity and destroying their temples, but the natives did not cooperate well with this plan.12 Spanish conquistadors soon realized that to govern the thousands of people in Mexico, they needed to understand the language and use interpreters to communicate with people. They did this by getting help from indigenous people who could translate Spanish into Nahuatl and vice versa.

One of the most famous interpreters in Mexican history was Doña Marina, whom they also called La Malinche. In 1519, when Cortés and his troops first landed on the Tabascan coast, he was met with hostility by the Tabascan people. However, Cortés and his troops relied on their superior weapons and military tactics, and the Tabascans backed down. To please the Europeans, the Tabascans gifted Cortés some slave girls. One of them, La Malinche, was a Mexican native princess. She became Cortés’ mistress and interpreter during his conquest of Mexico. She also helped him negotiate with natives in his search for gold and silver all throughout Mexico.13

Decades after the conquest, In 1560, King Charles of Spain declared that all Mexican natives had to be taught Spanish, but declaring a law is easier than actually putting it to action.14 As a matter of fact, Mexican natives clung to their language and traditions. Spanish Catholic priests decided to learn Nahuatl to understand the culture and traditions of the people they planned to convert. Priests, in fact, found it was easier to convert natives to Christianity if they could speak to them in Nahuatl and understand them clearly.15 As a result of the power and social dependence, Nahuatl became Mexico’s lingua franca, or official language.

The Spanish crown continued to discourage the use of indigenous tongues in Mexico throughout the next centuries. However, this did not affect Nahuatl in any way; it was still spoken all throughout the country, and Spanish conquistadors accepted it as beneficial to them. Since the Spanish crown was far from Mexico, in any case, they could not stop the continued usage of the Nahuatl language as they would have wanted to.16

It is known that a language can survive if its native speakers or its “conquerors” find a use for it and make it the official language of that society.17 Since the conquistadors did find benefits from using Nahuatl as the official Mexican language, Nahuatl continued to exist and be part of the traditional Mexican culture. However, although the conquest of Mexico did not end the Nahuatl language, the Spanish language did change and influence Nahuatl in various ways.

Some of the changes to the Nahuatl language were due to Spanish influence on it. This is shown in the adaptation of the orthographic conventions of Spanish’s Roman alphabet in the 1530s, which helped develop writing in Nahuatl.18 The changes continued. In fact, American linguists Frances E. Karttunen and James Lockhart believe “that as early as 1545 if not earlier, central Mexican Nahuatl had borrowed all the Spanish words for the days of the week and the months of the year”.19

Even though this does not mean that the Nahuatl language was changed drastically back then, there have been changes to the language that have become noticeable in modern times. According to recent studies, in Modern Nahuatl, there are borrowings of verbs and particles from Spanish, and the adoption of plural forms and sounds which did not exist in Classical Nahuatl.20 Linguists now determine three basic divisions of Modern Nahuatl based on how the Classical Nahuatl phoneme /ɬ/ changed. Central and northern Nahuatl varieties retained /ɬ/ (Nahuatl), eastern varieties replaced /ɬ/ with /t/ (Nahuat), and western varieties replaced /ɬ/ with /l/ (Nahual).21 In the long run, the greatest factor that caused change in the Nahuatl language was the influence of Spanish as evidenced by the many effects it had on the native tongue of the Aztecs.22

As time passed after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, Spanish did become the official language. This does not mean, however, that the Nahuatl language disappeared completely. Although some might argue that Nahuatl is a dead language, and that the Spanish language replaced Nahuatl as the dominant language23, the Nahuatl language has continued to be a living language in many parts of Mexico and the United States. According to the census of 2010, Nahuatl is still spoken in Mexico by about 1.54 million people.24 Most Nahuatl speakers are found in rural areas of the states Guerrero, Puebla, and San Luis Potosí, and it is estimated that at least 15% of these speakers are monolingual, meaning they only speak Nahuatl.25 The history of the Nahuatl language, and the many changes it went through, is part of Mexican culture and history. For this reason, we should try to pass the language to future generations and study more about it, since it is an example of the effects that colonization has on the indigenous languages of those colonized.

- History.com Editors, “Aztec capital falls to Cortes,” History, February 9, 2010, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/aztec-capital-falls-to-cortes. ↵

- “Nahuatl”, Must Go, https://www.mustgo.com/worldlanguages/nahuatl/#:~:text=The%20Nahua%20peoples%20are%20thought,dominant%20people%20in%20central%20Mexico. ↵

- Lyle Campbell, “Uto-Aztecan languages,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 20, 1998, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Uto-Aztecan-languages/additional-info#history. ↵

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Nahua,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 20, 1998, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nahua/additional-info#history. ↵

- Elias Beck, “Toltec,” History Crunch, August 15, 2018, https://www.historycrunch.com/toltec.html#/. ↵

- Edward Anthony Polanco, “Tips on Pronouncing Nahuatl,” Edward Anthony Polanco, PhD, April 4, 2017, https://eapolanco.com/tips-on-pronouncing-nahuatl/. ↵

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Glottal stop,” Encyclopaedia Brittanica, July 20, 1998, https://www.britannica.com/topic/glottal-stop. ↵

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Nahuatl language,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, March 22, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nahuatl-language. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- Christopher Minster, “The Treasure of the Ancient Aztecs,” ThoughtCo, February 25, 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/the-treasure-of-the-aztecs-2136532. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- Mark Cartwright, “Cortés & the Fall of the Aztec Empire,” World History Encyclopedia, July 4, 2016, https://www.ancient.eu/article/916/cortes–the-fall-of-the-aztec-empire/. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- Nathan Bierma, “Impact of Cortez’s conquest is still felt today in Mexico,” Chicago Tribune, April 12, 2006, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2006-04-12-0604120005-story.html. ↵

- Justyna Olko and John Sullivan, “Empire, Colony, and Globalization. A Brief History of the Nahuatl Language,” Colloquia Humanistica (2015):190-98. ↵

- Frances E. Karttunen and James Lockhart, Nahuatl in the Middle Years: Language Contact Phenomena in Texts of the Colonial Period (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), 233-35. ↵

- Justyna Olko and John Sullivan, “Empire, Colony, and Globalization. A Brief History of the Nahuatl Language,” Colloquia Humanistica (2015):190-98. ↵

- “Nahuatl”, Must Go, https://www.mustgo.com/worldlanguages/nahuatl/#:~:text=The%20Nahua%20peoples%20are%20thought,dominant%20people%20in%20central%20Mexico. ↵

- Nicolás del Castillo, “Nahuatl: The Influence of Spanish on the Language of the Aztecs,” Journal of the American Society of Geolinguistics 38, (2012). ↵

- Nicolás del Castillo, “Nahuatl: The Influence of Spanish on the Language of the Aztecs,” Journal of the American Society of Geolinguistics 38, (2012). ↵

- John Schmal, “The Mexican Census,” Somos Primos, March 10, 2019, http://www.somosprimos.com/schmal/mexicancensus.htm. ↵

- Nicolás del Castillo, “Nahuatl: The Influence of Spanish on the Language of the Aztecs,” Journal of the American Society of Geolinguistics 38, (2012). ↵

32 comments

Melyna Martinez

I believe this article is a great way to showcase the importance of native languages, and Nahulat is so important to Mexican culture. I believe this article those a great way of showcasing how the Spanish in order to incorporate themselves into the language tried and learned it. Not only that but you can see that after years of contact with Spanish words where taken and incorporated, which is pretty amazing.

Sydney Nieto

Congratulations on your award. This article was well-written and very informative. Firstly, I found it interesting on how Nahuatl became Mexico’s official language, at the time, even though King Charles wanted Mexican to learn Spanish. And how the priest would try to learn to understand them. Then how it slowly converted to Spanish over time, making it the new official language. Overall, interesting article.

Donald Glasen

This article was very interesting. I found it interesting to see how the Nahuatl language works. Language truly is part of one’s identity, and a display of one’s culture as well. It’s nice to see that the Nahuatl language isn’t did and that it is still spoken.

Lorena Martinez Canavati

This was a very interesting article. I loved how you described language phonology. You also described in depth how Nahuatl language works. I don’t think it’s a dead language because people still speak it, but I do think it could become a dead language if all speakers pass and don’t teach it to future generations. I agree that it’s important to pass the language on because it’s part of Mexican cultural heritage. Congratulations on this article, really well written.

Christopher Morales

Language is more than the noises you make. We see here that language is a part of the identity a person has. After the Spanish used their advanced weapons against the Aztecs, they wanted to essentially change them to the standards in which were normal for Cortes and his homeland. They wanted to change the religion, language, and lives of a people who did not want to. Language is a beautiful thing that can show expression and identity. While we do not recognize it all the time, it is one of the most important things we own. It is beautiful and represents the strength to preserve identity that the language survived till this day.

Eugenio Gonzalez

First of all, congratulations on your winning article. The article was informative; previously to reading the article, I did not know much about the Nahuatl language. Reading about the origin of the Nahuatl language and how the Uto-Aztecans migrated to central Mexico was interesting. I was surprised that 1. 54 million people still speak Nahuatl; knowing this gives hope that Nahuatl will not be a forgotten language and that future generations will continue to speak it.

Jaedon E

Great article! What I did find interesting was how the Spaniards decided if they couldn’t effectively communicate with the Natives they might as well learn the language. Eventually going to conquer land and continue to push Native land til there is no more. One thing that did allow Cortes to conquer the Natives was the effects of epidemic disease. Due to smallpox exponentially, so the Aztecs couldn’t fight off diseases and defend themselves.

Melyna Martinez

This article shows the impacts of the native language and how Nahualt still is spoken today. I believe native languages hold importance and how they impact the way other languages say words not only in Spanish but in English as well. Nahulth though is today one of the most spoken native languages in the world and impacts Mexican culture on a daily, as well it is mostly and oral language rather than a written one.

Noelia Torres Guillen

I enjoyed this article because I had to idea that the Nahuatl language was still spoken. It makes a lot of sense though, especially with how it influenced the Spanish language and vise versa. I like the fact that the indigenous peoples persisted on keeping their language. Spanish conquistadores and priest realized that they had to either have interpreters to speak with the natives and to convert them to Catholicism. It is great that natives have kept and are keeping something so important to their culture alive. Great work!

Anayetzin Chavez Ochoa

My name is from the Nahuatl language, so upon seeing the title, I–of course– had to read it for myself. I know for many words that didn’t exist in the Nahuatl language, the natives took from the Spanish, like “Cahuayoh/Kawayoh” for the word ‘Horse’ because they didn’t have horses until the Spanish came. And in turn, the Spanish took from the Nahuatl language for words like ‘Aguacate (Avocado)’ from the native word ‘A(g/h)uacatl’ as you mentioned. Other examples include ‘Coyotl (Coyote)’, ‘Chapulin (Grasshopper),’ and ‘Ocelote (Ocelot)’. I didn’t know Comanche was part of the Nahuatl family, nor did I realize so many people spoke it, so thank you for informing us! I never hear it when I visit my family, and I think it’s a beautiful language!