Many of us know that the Spanish conquest of Latin America brought tremendous change to those regions. In Mexico specifically, Spanish conquest ended one of the most powerful and developed empires in Latin America, which was the Aztec empire. This led to many changes and one of them was the effects the Spanish language had on the Nahuatl language.

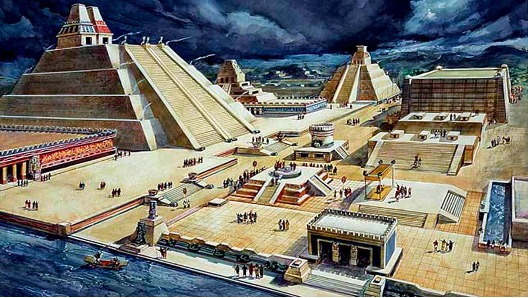

In the year 1521 the Aztec empire fell due to Spanish colonization. Hernán Cortés, the Spaniard in charge of the expedition to Mexico, and his men captured and killed the Aztec emperor Montezuma II, due to Montezuma II’s uncertainty on how to react to the Spaniards. The emperor believed Cortés was an Aztec god who was prophesied to bring universal peace to the Aztec empire. After his death, Montezuma II was replaced by his brother Cuitlahuac, whose leadership pushed away Cortés and his people. Cuitlahuac later died of smallpox, which also killed much of the Aztec population. This, in fact, led the empire to its weakest point and, with, the help of neighboring tribes including the Texcocans, Chalca, and Tepanec, Cortés placed Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital under a three-month siege. He accomplished defeating the strong and resistant Aztec empire after his many earlier failed attempts to do so.1

The history of Nahuatl is fascinating, yet complicated. The term “Nahuatl” literally means “something that sounds good and clear”. Classical Nahuatl was the administrative language of the Aztec empire that served as a lingua franca in Central America from the 7th to the 16th century AD, when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the New World. Nahuatl speakers, or the Nahua people, are thought to have originated in what is now the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico.2 It is believed that the Nahua split from other Uto-Aztecans, who were people who spoke any of the languages that belong to the Uto-Aztecan language family, such as Comanche, Hopi, Nahuatl, Paiute, Pima, and Shoshone.3After this split, around 500 AD, the Nahua migrated to the central part of Mexico, eventually spreading throughout Mexico.4 Nahuatl served as the language for the Toltec empire, a powerful empire founded by the Nahua that ruled the central part of Mexico from the 10th to mid-12th centuries AD. After its fall, Nahuatl served as language for the Aztec empire, which dominated Mexico from 1325 to 1521.5

Nahuatl was known for its use of a “tl” sound as a single consonant. This sound, /ɬ/, the alveolar lateral affricate, was pronounced by placing the tongue in the position to pronounce the letter “t,” while pushing air out from both sides of the tongue.6 Nahuatl phonology was also known for the glottal stop, an interruption on the airstream by closing the glottis (the space between the vocal cords), which causes the vocal cords to stop vibrating. Upon release, there is a slight choke, or cough like explosive sound.7 Classical Nahuatl used a set of 15 consonants and four long and short vowels. It was also considered to have agglutinative grammar, in that it used prefixes and suffixes, compound words, and it doubled syllables. Nahuatl added different affixes, prefixes, and/or suffixes to roots to form long words. Then the words as a whole functioned as a sentence does in English.8

The Spanish colonization of Mexico brought many changes to the already well-structured and developed civilization. Tenochtitlán itself was rebuilt into a Spanish-style capital city, which they called La Cuidad de México (Mexico City).9 Two of the main reasons why Spanish conquistadors arrived in Mexico in the first place was to look for gold10 and to convert the natives to Christianity.11 After the defeat of the Aztec empire and thus, the vast majority of the population of Mexico, the Spaniards took on the mission of achieving these initial goals.

At first Spanish conquistadors tried to persuade natives to learn Spanish, after converting them to Christianity and destroying their temples, but the natives did not cooperate well with this plan.12 Spanish conquistadors soon realized that to govern the thousands of people in Mexico, they needed to understand the language and use interpreters to communicate with people. They did this by getting help from indigenous people who could translate Spanish into Nahuatl and vice versa.

One of the most famous interpreters in Mexican history was Doña Marina, whom they also called La Malinche. In 1519, when Cortés and his troops first landed on the Tabascan coast, he was met with hostility by the Tabascan people. However, Cortés and his troops relied on their superior weapons and military tactics, and the Tabascans backed down. To please the Europeans, the Tabascans gifted Cortés some slave girls. One of them, La Malinche, was a Mexican native princess. She became Cortés’ mistress and interpreter during his conquest of Mexico. She also helped him negotiate with natives in his search for gold and silver all throughout Mexico.13

Decades after the conquest, In 1560, King Charles of Spain declared that all Mexican natives had to be taught Spanish, but declaring a law is easier than actually putting it to action.14 As a matter of fact, Mexican natives clung to their language and traditions. Spanish Catholic priests decided to learn Nahuatl to understand the culture and traditions of the people they planned to convert. Priests, in fact, found it was easier to convert natives to Christianity if they could speak to them in Nahuatl and understand them clearly.15 As a result of the power and social dependence, Nahuatl became Mexico’s lingua franca, or official language.

The Spanish crown continued to discourage the use of indigenous tongues in Mexico throughout the next centuries. However, this did not affect Nahuatl in any way; it was still spoken all throughout the country, and Spanish conquistadors accepted it as beneficial to them. Since the Spanish crown was far from Mexico, in any case, they could not stop the continued usage of the Nahuatl language as they would have wanted to.16

It is known that a language can survive if its native speakers or its “conquerors” find a use for it and make it the official language of that society.17 Since the conquistadors did find benefits from using Nahuatl as the official Mexican language, Nahuatl continued to exist and be part of the traditional Mexican culture. However, although the conquest of Mexico did not end the Nahuatl language, the Spanish language did change and influence Nahuatl in various ways.

Some of the changes to the Nahuatl language were due to Spanish influence on it. This is shown in the adaptation of the orthographic conventions of Spanish’s Roman alphabet in the 1530s, which helped develop writing in Nahuatl.18 The changes continued. In fact, American linguists Frances E. Karttunen and James Lockhart believe “that as early as 1545 if not earlier, central Mexican Nahuatl had borrowed all the Spanish words for the days of the week and the months of the year”.19

Even though this does not mean that the Nahuatl language was changed drastically back then, there have been changes to the language that have become noticeable in modern times. According to recent studies, in Modern Nahuatl, there are borrowings of verbs and particles from Spanish, and the adoption of plural forms and sounds which did not exist in Classical Nahuatl.20 Linguists now determine three basic divisions of Modern Nahuatl based on how the Classical Nahuatl phoneme /ɬ/ changed. Central and northern Nahuatl varieties retained /ɬ/ (Nahuatl), eastern varieties replaced /ɬ/ with /t/ (Nahuat), and western varieties replaced /ɬ/ with /l/ (Nahual).21 In the long run, the greatest factor that caused change in the Nahuatl language was the influence of Spanish as evidenced by the many effects it had on the native tongue of the Aztecs.22

As time passed after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, Spanish did become the official language. This does not mean, however, that the Nahuatl language disappeared completely. Although some might argue that Nahuatl is a dead language, and that the Spanish language replaced Nahuatl as the dominant language23, the Nahuatl language has continued to be a living language in many parts of Mexico and the United States. According to the census of 2010, Nahuatl is still spoken in Mexico by about 1.54 million people.24 Most Nahuatl speakers are found in rural areas of the states Guerrero, Puebla, and San Luis Potosí, and it is estimated that at least 15% of these speakers are monolingual, meaning they only speak Nahuatl.25 The history of the Nahuatl language, and the many changes it went through, is part of Mexican culture and history. For this reason, we should try to pass the language to future generations and study more about it, since it is an example of the effects that colonization has on the indigenous languages of those colonized.

- History.com Editors, “Aztec capital falls to Cortes,” History, February 9, 2010, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/aztec-capital-falls-to-cortes. ↵

- “Nahuatl”, Must Go, https://www.mustgo.com/worldlanguages/nahuatl/#:~:text=The%20Nahua%20peoples%20are%20thought,dominant%20people%20in%20central%20Mexico. ↵

- Lyle Campbell, “Uto-Aztecan languages,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 20, 1998, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Uto-Aztecan-languages/additional-info#history. ↵

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Nahua,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 20, 1998, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nahua/additional-info#history. ↵

- Elias Beck, “Toltec,” History Crunch, August 15, 2018, https://www.historycrunch.com/toltec.html#/. ↵

- Edward Anthony Polanco, “Tips on Pronouncing Nahuatl,” Edward Anthony Polanco, PhD, April 4, 2017, https://eapolanco.com/tips-on-pronouncing-nahuatl/. ↵

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Glottal stop,” Encyclopaedia Brittanica, July 20, 1998, https://www.britannica.com/topic/glottal-stop. ↵

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Nahuatl language,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, March 22, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nahuatl-language. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- Christopher Minster, “The Treasure of the Ancient Aztecs,” ThoughtCo, February 25, 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/the-treasure-of-the-aztecs-2136532. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- Mark Cartwright, “Cortés & the Fall of the Aztec Empire,” World History Encyclopedia, July 4, 2016, https://www.ancient.eu/article/916/cortes–the-fall-of-the-aztec-empire/. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- John P. Schmal, “The Aztecs are Alive and Well: The Nahuatl Language in Mexico,” 2004, http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html. ↵

- Nathan Bierma, “Impact of Cortez’s conquest is still felt today in Mexico,” Chicago Tribune, April 12, 2006, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2006-04-12-0604120005-story.html. ↵

- Justyna Olko and John Sullivan, “Empire, Colony, and Globalization. A Brief History of the Nahuatl Language,” Colloquia Humanistica (2015):190-98. ↵

- Frances E. Karttunen and James Lockhart, Nahuatl in the Middle Years: Language Contact Phenomena in Texts of the Colonial Period (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), 233-35. ↵

- Justyna Olko and John Sullivan, “Empire, Colony, and Globalization. A Brief History of the Nahuatl Language,” Colloquia Humanistica (2015):190-98. ↵

- “Nahuatl”, Must Go, https://www.mustgo.com/worldlanguages/nahuatl/#:~:text=The%20Nahua%20peoples%20are%20thought,dominant%20people%20in%20central%20Mexico. ↵

- Nicolás del Castillo, “Nahuatl: The Influence of Spanish on the Language of the Aztecs,” Journal of the American Society of Geolinguistics 38, (2012). ↵

- Nicolás del Castillo, “Nahuatl: The Influence of Spanish on the Language of the Aztecs,” Journal of the American Society of Geolinguistics 38, (2012). ↵

- John Schmal, “The Mexican Census,” Somos Primos, March 10, 2019, http://www.somosprimos.com/schmal/mexicancensus.htm. ↵

- Nicolás del Castillo, “Nahuatl: The Influence of Spanish on the Language of the Aztecs,” Journal of the American Society of Geolinguistics 38, (2012). ↵

32 comments

Jose Maria Gallegos Cebreros

First of all congrats on a great article! I enjoyed learning your article quite a lot. I never really thought how did the Spaniards communicate with the tribes, and finding out that they learned Nahuatl surprised me a lot. Obviously, it was a completely different language and less sophisticated than Spanish and it surprised me that they learned it. Great content!

Kristen Leary

I think the subject of a language like this is such a fascinating research topic. It is surprising to hear that 1.54 million people in Mexico still speak Nahautl, especially since Spanish has dominated so many regions of the Americas. One thing I found interesting is that the Spanish settlers found Nahautl to be beneficial to them, so that is perhaps why it has survived even if Spanish became the official language. Missionaries found it better to connect with the indigenous people if they knew and understood their language, and the Spanish language adopted many words as well.

Anna Steck

Language barriers, changes, and its impact on culture are very fascinating to me. It is interesting to think about how those language differences would have affected the conquistadors and the Aztecs and other indigenous groups. Missionaries learned Nahuatl and the Aztecs learned Spanish. Of course these things were affected by each other. It is exciting that Nahuatl lives on today and it is a way that many can connect to their heritage.

Lauren Deleon

I enjoyed reading this article because it was very well written and it’s contents are not only relevant to the World History course I am taking this semester, but also to my Linguistics course. I was very excited that you talked about the phonology of the language, in particular how it utilized the glottal stop, because we just finished our Phonetics section in that class. Well done!

Adelina Wueste

This article was so informative! I had no idea that Spanish priests and conquistadors leaned Nahuatl in order to communicate with natives. I had always assumed that natives were forced into speaking Spanish without anyone learning their language. I liked the image you added of certain words that derive from Nahuatl words (like Chocolate, Tomate, and Aguacate). It was interesting to see that the Nahuatl “tl” sound seems to have carried over to Spanish as the “e” sound. I personally think it’s incredible how the language of people who were driven away from their language, is still being used in the modern day.

Gabriella Parra

I thought it was so interesting that there are so many people that speak Nahuatl today! I love the evolution of language, but I usually see it applied to dead languages or those that originally used the roman alphabet. It’s also interesting how the language has splintered a bit. Since the “tl” sound is what made the language unique, it’s fascinating that some Nahuatl speakers have strayed away from that original sound. I’d like to research a list of words we use in English today that have come from Nahuatl.

Lucia Herrera

I really enjoyed reading this article and learning about the Native people who were insistent on keeping their language and culture after their temples were destroyed. I think this article shows the bravery of the natives from defying their King’s ruling and continue to reject the Spanish language. It was interesting that the conquistadors decided to learn Nahuatl to teach them about their culture and Christianity. Moreover, I find it disappointing that Nahuatl is not common in the Spanish language because I struggle in pronouncing some of these native words. I am glad to have learned that the language has not disappeared after all these years.

Hali Garcia

Congratulations on winning an award!!! It’s well deserved! I really enjoyed reading this article and it was very informative. I liked how you explained how they pronounced the “tl” consonant. I really love learning about different languages and how they are spoken and this article really taught me a lot about the language and how the people continued to speak their language even though the Spanish wanted them to speak Spanish. I was also struck by how many people still speak Nahuatl. I also liked the picture where it showed the translation between English, Spanish, and Nahuatl. Great Job!

Alicia Reyes

I thought it was very impressive of the Native people to be insistent on keeping their language and culture after their temples were destroyed. It was very brave of them to defy the King’s ruling and continue to reject the Spanish language. It was interesting that the conquistadors decided to learn Nahuatl to teach them about their culture and Christianity. Moreover, I find it disappointing that Nahuatl is not common in the Spanish language because I struggle in pronouncing names like Popocatepetl and Xochiquetzal. I am glad to have learned that the language has not disappeared after all these years even though I am not familiar with it.

Katelyn Espinoza

I had always been told that Nahuatl was a deal language and that no one could speak it anymore. However, it is crazy to think that over a million people still know it! I really enjoyed your inclusion of La Malinche. She’s a very prominent figure in Latino culture- specifically when you are trying to call someone a traitor! Getting to relearn everything I know about her was a great refresher on Aztec history. Marvelous job and congratulations on your award!