Huntington’s Disease (HD) is a debilitating and ultimately fatal illness that is characterized, most notably, by its main symptom of chorea, which is the term for the generalized, uncontrollable, and unpredictable muscle movements patients experience. Originating in the genome, it’s a hereditary disease that often manifests later in life, but its onset can be hastened by an increase of certain genetic markers. Seeing as neurodegenerative diseases are becoming more prevalent and manifesting sooner, it’s worthwhile to review relevant literature and understand the history of one such case: HD. In addition, it is important to increase awareness on HD, and inform the general public on how current research is fighting to develop new therapies in order to improve patient symptoms and quality of life.

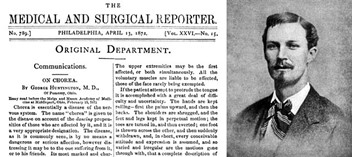

In order to more properly understand the gravity of HD, as well as its origins, a bit of background information is required. The disease was first characterized clearly and in detail by George Huntington and was generally called Chorea, based on the main symptom, prior. It was also recognized as a hereditary condition. As the disease affects the brain’s neural cells, which die, the person experiences issues with their nervous system and cognition. In fact, the symptoms exhibited by patients could have been a driving factor of the Salem witch trials, where patients were thought to have been possessed. It is also important to note, that the disease is thought to have been brought to North America from the United Kingdom by early settlers. Several generations later, as a boy, George Huntington had been traveling with his father and came across a couple stricken by chorea, as it was known before. Upon meeting and speaking to them, it seems he had a revelation of purpose and developed a profound interest in studying the disease. In his memoirs he wrote, “Over fifty years ago, in riding with my father on his professional rounds, I saw my first case of ‘that disorder’, which was the way in which the natives always referred to the dreaded disease. It made a most enduring impression upon my boyish mind, an impression every detail of which I recall today, an impression which was the very first impulse to my choosing chorea as my virgin contribution to medical lore.”1

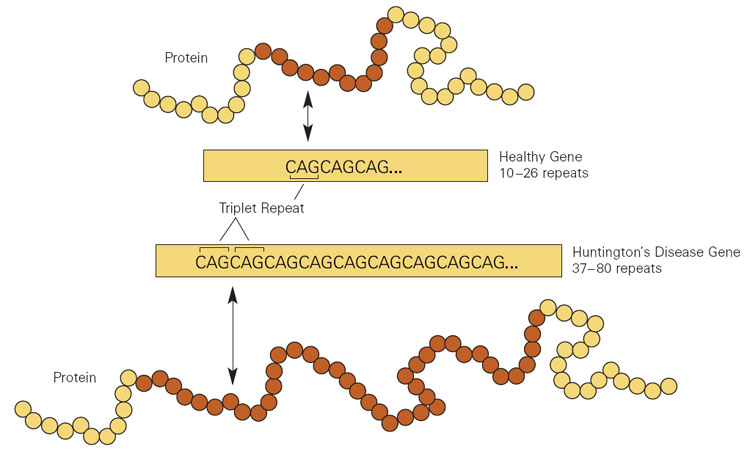

It took over a hundred years before anyone was able to find the true source and cause of the disease, and it was eventually done by James Gusella and multiple other geneticists under his guidance at Harvard Medical School in the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1983. Aided by more advanced technology, their analysis showed that the gene responsible for HD was located on the short arm of chromosome 4. It was later concluded by Anita Harding, at Queen Square, London, England, UK that a repeat series of the same three nucleotides: CAG (cytosine, adenine, and guanine) were related to the overall severity of HD.2

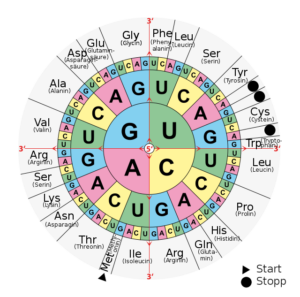

If this sounds confusing, there is a pretty concise and straightforward way of thinking about this. In order to better understand how a trinucleotide sequence can cause an entire debilitating disease, we must think about the Central Dogma. This is basically a theory describing how genetic information “flows”, much like a river, in one direction. This flow generally starts at DNA (sometimes directly from RNA to protein), which is then transcribed to RNA, and is lastly translated into a protein.3 The “alphabet” that RNA polymerase reads to build specific messenger RNA is comprised of the letters A, T, G, and C in DNA (A, U, G, and C for RNA), in different combinations, which you can think of like words on a page. These will read out as different proteins, after ribosomal synthesis, depending on the sequence.4 Therefore, a mistake in this process, or a mutation, will logically lead to either no protein, one with a dysfunction, or even a whole new protein function; this is often the cause of many diseases.5 In the case of HD, the severity is tied to an increase in the abnormal number of CAG (CAG coding for the amino acid glutamine) repeats (past 35) that are part of the polyglutamine (CAGCAGCAG…), or polyQ, region of the huntingtin gene (HTT), which translates into the protein called Huntingtin (HTT). Typically, around 40-50 repeats are needed to develop the disease in adulthood, but the age of onset decreases greatly as the associated repeat number increases. This protein is also currently understood to be involved in a whole host of different biological processes and is even expressed in great numbers, in its normal form, during development. The death of medium-sized spiny neurons in the striatum of the brain, an effect of high numbers of mutant protein aggregates, is a prime characteristic of the disease. This is particularly relevant due to the striatum being a portion of the brain where these neurons are involved in regulating motor functions. Evidently, a mutant HTT, or one with an expanded polyQ region, is misfolded and cannot be fixed, develops new toxic characteristics by aggregating with itself and other important proteins, subsequently overloads regulatory mechanisms (such as ubiquitin tagging and subsequent degradation of the abnormal protein by the proteasome), and even loses the ability to perform some original functions, such as trafficking from the nucleus towards the cytoplasm, resulting in accumulation and cell death.6

As stated before, Huntington’s disease is a hereditary, incurable genetic disease that is characterized by accelerated neurodegeneration over the course of one’s lifetime. Because it displays an autosomal (located on a non-sex chromosome) dominant pattern of inheritance, there is around a 50% chance that a child with a parent who has the disease will also receive the mutated gene. From that point, the number of repeats will decide whether or not the disease will manifest and at what general point in their lifetime. It’s also possible that a lower number of repeats (around 27+), which is still outside the norm, will not always lead to the development of the disease, but will still allow it to be passed on. There is, however, the possibility of developing sporadic HD, meaning the gene mutates in a person who did not inherit the mutation nor has a family history of the disease. This is much more rare, though.

As the person with the mutation grows up, they eventually begin to exhibit their first symptoms. Early on, it usually manifests as a series of symptoms that aren’t unique to HD, and often mirror those of other behavioral disorders. Patients who are initially unaware of any maladies begin to experience mood swings, more violent outbursts, and other psychiatric events. Once a patient has reached a point where the disease infiltrates their everyday life and affects their cognition to a high enough degree, they are characterized as exhibiting dementia.7 In fact, psychological manifestations of the disease eventually become so overwhelming that the second leading cause of death in those with Huntington’s disease is suicide, right behind lung infections, and most victims are usually those who were symptomatic earlier. These psychological manifestations are usually incredibly varied, ranging from generalized anxiety and impatience to OCD, and even hypersexuality in the earlier stages. However, eventual weight loss and associated apathy make diagnosis difficult, as the patient loses individuality and stops self-advocating or caring about most things. Sadly, these symptoms often severely impact the patient’s interpersonal relationships, both intimate and professional. This all occurs before their motor skills become impaired, as the entire musculoskeletal system can become affected by the disease. As it progresses, HD becomes increasingly effective at removing a person’s ability to perform everyday tasks. Chorea is generalized and manifests during virtually all waking hours, their gait can change dramatically, and even the patient’s ability to speak can be completely lost. Independent of psychological effects, motor impairment will severely decrease the patient’s quality of life if left untreated. Juvenile HD (usually occurring in patients with over 53 repeats) is a bit more nuanced and can be responsible for social issues and a lack of academic success, as well as the common occurrence of epileptic seizures. On the diagnostic side of things, the disease is usually confirmed by an evaluation of motor skills, family history, and even genetic testing, the latter of which may require additional genetic counseling for the patient at risk, seeing as the time period around genetic testing is known to be particularly dangerous for suicidal individuals.8

Unfortunately, much like with other neurodegenerative illnesses, there is no drug or therapy that can stop or cure the disease’s progression. The outcome remains fatal and, at present, current drugs, such as Tetrabenazine, can only manage the symptoms and improve a patient’s quality of life as much as possible. These drugs work by suppressing the hallmark symptom of HD, chorea, and their use is usually complimented by medications that target other, more psychological aspects of the disease. In short, current methods of treatment involve the administration of anti-choreic medication and the management of mood or other psychiatric disorders. Apart from medications, there is also a substantial contribution towards overall patient comfort that is provided by way of physical therapy and other non-invasive interventions. As a person’s motor ability deteriorates, it becomes more important to ensure that they can still get around comfortably and perform normal tasks to the best of their ability. Additionally, mute patients can meet with experts who will provide them with the means to communicate with their family and others. These include electronic speaking devices, among other intermediary equipment such as charts. It’s also best to combine these lifestyle changes with medication in order to achieve some sort of stability for the patient. Furthermore, patients can receive counseling and therapy to deal with the psychological stress involved with a diagnosis or progressing disease, and if their ability to swallow is compromised, their nutrition can be supplied and administered as needed. Because HD is known to be worsened by an increase in protein aggregates, future therapy development is focusing on the deep-lying cause behind the disease, rather than “downstream effects”, by way of targeting messenger RNA (mHTT). By being able to change how much of the offending protein is expressed, the assumed hope is that a therapeutic effect will manifest as either less severe symptoms or a delay in the progression of the disease. Some more potential methods of treatment include the excision of the mutated polyQ region by CRISPR and the introduction of stem cells that could replace neurons lost.9

A diagnosis of Huntington’s disease is undeniably one of the most devastating that a person can receive, and such is the case with other neurodegenerative diseases. It is an initially silent killer that gradually robs its victims of their sanity, physical autonomy, and even sense of self. As genetic screening becomes more common and affordable, there is a possibility that those who carry the mutation will second-guess starting a family once they have prior knowledge of the risks. It can be inferred that some may even be aware that they carry the mutation due to a family history of the disease, but may choose not to receive a potentially devastating diagnosis that will cause them unwanted anxiety and psychological stress up until the onset of symptoms.10 In any case, HD is only becoming more and more researched every year and continued advancements in technologies will only serve to expedite the journey towards a possible cure for it.

- Huntington, G. (1872). On chorea. The Medical and Surgical Reporter of Philadelphia. cited in H. Skirton (2005),‘Huntington’s Disease: a nursing perspective’, MedSurg Nursing, 14(3), 167-174. ↵

- Bhattacharyya, K. B. (2016). The story of George Huntington and his disease. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 19(1), 25–28. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-2327.175425 ↵

- Ostrander, E. (2023, October 17). Central dogma. Genome.gov. https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Central-Dogma ↵

- Mercadante AA, Dimri M, Mohiuddin SS. Biochemistry, Replication and Transcription. (Updated 2023 Aug 14). In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540152/ ↵

- Durland, J., & Ahmadian-Moghadam, H. (2022). Genetics, Mutagenesis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. ↵

- Schulte, J., & Littleton, J. T. (2011, January 1). The biological function of the Huntingtin protein and its relevance to Huntington’s disease pathology. Current trends in neurology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3237673/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Huntington’s disease. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/huntingtons-disease#toc-who-is-more-likely-to-get-huntington-s-disease- ↵

- Andhale R, Shrivastava D (August 27, 2022) Huntington’s Disease: A Clinical Review. Cureus 14(8): e28484. doi:10.7759/cureus.28484 ↵

- Ferguson, M. W., Kennedy, C. J., Palpagama, T. H., Waldvogel, H. J., Faull, R. L. M., & Kwakowsky, A. (2022, May 21). Current and possible future therapeutic options for Huntington’s disease. Journal of central nervous system disease. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9125092/ ↵

- UC Davis Health, D. of N. (n.d.). Genetics – pre-symptomatic testing. https://health.ucdavis.edu/huntingtons/genetics-presymptom.html ↵