Implications of Post-Colonial Economic Structures in Ghana

In Ghana’s Ashanti region, at the cocoa plantations, a third-generation farmer watched the prices of his crops ebb and flow like the whimsical tides. His grandfather prospered in the 1960’s cocoa boom, dreaming of the day Ghana grew not just cocoa but built its own chocolate dynasty. Two decades later, he still marketed his beans to foreign companies that shipped them for processing overseas, while his village suffered from poor roads and derelict schools. When cocoa prices dropped, so did his revenues, just like when gold faltered. With all the grandstanding about industrialization, Ghana remained mired in exporting raw materials, one of colonialism’s curses which saw profits escape while leaving the producers carrying the risks. When politicians talked about a ‘Ghana Beyond Aid’,” he wondered: when would his country break free of its past to forge a future of its own, benefiting its people?1

Even when one cannot claim that all security problems in Ghana came from its colonial legacy, to address policy corruption and inefficiency, one must examine how British Colonial Rule continues impacting security negatively in Ghana today.2 Structural adjustment programs, privatization, and deregulation fostering economic liberalization cemented poverty and social exclusion, in the city slums and also in the rural and northern parts of Ghana. This has contributed to rising crime levels and placed additional stress on Ghana’s law enforcement agencies. Economic post-colonial structures in Ghana inherited after the centralization of control over the police greatly impacted national security and social stability by entrenching economic inequality and decreasing the effectiveness of law enforcement.

The Ghanaian Police Service, while integral to maintaining order, faces growing challenges from lack of funding, inadequate resources, and low pay that fuels corruption resulting in low public trust. The collapse of traditional social support structures, combined with an undermined policing infrastructure, have heightened insecurity. Historically, family networks provided economic security, but modernization and market-oriented policies undermined these traditional societal safety nets. These issues require an integrated strategy that supports both economic safety nets and adequately funds law enforcement to build internal capacity and long-term stability.

Ghana’s Structural Dependence on Commodities

Many African countries have undergone unequal development where some sectors of their economy seemingly thrive, while others decline or persist in poverty. Ghana remains over reliant on exporting unrefined natural resources have seldom been able to overcome the instability of commodity prices (gold, oil, cocoa, its primary exports) nor have they been able to maximize revenue to foster long term economic development.3 Economic development theory assumes that an abundance of resources should provide the foundation for development through the mitigation of capital bottlenecks as well as the fiscal stimulus to drive industrialization. The big push hypothesis argues that revenue obtained from natural resources such as oil, minerals, and cash crops could help the developing economies to solve capital bottlenecks and invest in industry, infrastructure, as well as human capital. Empirical experience, on the other hand, provides evidence against this hypothesis, stating that most economies rich in resources, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa, instead experience economic stagnation, volatility, as well as underdevelopment rather than long-term development. This paradox is referred to as the resource curse, suggests that excessive reliance on primary products renders the process of diversification unfeasible, subjects the economy to foreign shocks, and leads to political as well as social instability.4

Ghana is a prime example of the resource curse because its economy remains structurally dependent on primary natural resources such as cocoa, gold, and oil. While such commodities earn high foreign exchange earnings, they also subject the country to the whims of world price fluctuations. Structuralist theory highlights the failure of primary commodity-dependent economies to achieve long-term development. They argue that primary commodities face long-term degradations in the terms of trade like the relative prices of such items decline compared to manufactured products in the long run. Such is corroborated by the income inelasticity of demand for raw material. As the world incomes increase, demand for primary products also remains flat compared to demand for industrial and technological products. Raw material export economies end up being structurally disadvantaged and unable to accumulate wealth as fast as the industrialized world.5

The dependence that exists structurally in Ghana has worsened economic unpredictability, fueled regional inequalities, and led to political unpredictability. The nation’s southern region, which mainly depends on the production of cocoa and gold, disproportionately gains from economic activity, with the northern regions being undeveloped. This further perpetuates economic and social inequalities.6 Commodity price volatility also creates fiscal unpredictability, hindering the government’s ability to create long-term development strategies. Political instability also commonly occurs hand in hand with such economic vulnerability since the unstable revenue that comes with natural resources poses a problem to the government in terms of governing, managing, and economic development cycles.7

The History of Colonial Policing in Ghana

The colonial police history of Ghana follows the trend of European imperial expansion and involves aspects of domination and subordination. African societies had no bureaucratic policing systems before colonization, although in the Ashanti Empire, with its bureaucratized state, there were specialist forces such as the Akwansrafo (patrolmen of trade routes who guarded trade routes) who regulated the movement of people, and the payment of taxes. These indigenous systems with the onset of British colonialism, yielded to a novel police system aimed at enforcing the colonial state’s definition of order. The establishment of a formalized system of police on the Gold Coast was largely a response to the 1864 riots that resulted from military confrontations with the civilian population. As a response to the riots, the British introduced a para-military police force to deal with internal security, although its growth was compromised by budgetary constraints and inadequate commitment to deploying a quality-trained, reasonably well-paid force. Through the early decades of the 20th century, socio-economic changes like the urbanization process, the spread of a money economy, and the cocoa boom, acted to heighten crime, most visibly the phenomenon of highway robbery in major towns such as Kumasi, Tarkwa, and Accra. The colonial authorities responded to this by introducing novel forms of policing, such as profiling and the upkeep of a habitual criminals list, although neither was directed at the causes of crime and did little to tackle the underlying social and economic factors that contributed to crime. The core problem was the lack of legitimacy. The colonial police force was not viewed as a guardian of the people but as an instrument of an oppressive state. The people viewed the police with suspicion and animosity as they had no function of protecting the people but to consolidate imperial authority and suppress opposition. The distance between the colonial police and the local people was an exact replica of the overall nature of colonial government. African subjects were not viewed as citizens but as items to be exploited, good only as long as they could yield wealth for the benefit of the British Empire.8

In June 2021, Ejura in Ghana’s Ashanti Region became the subject of national concern after social activist and #FixTheCountry campaigner Ibrahim “Kaaka” Mohammed was killed. His murder, which has widely been ascribed to his vocal criticism of local authorities, was followed by protesters rallying in the streets because they demanded justice and answers. It further escalated after soldiers deployed to quell protests opened fire on protesters, killing two and injuring others. In an aftermath, the administration formed a ministerial committee to look into what had transpired, the incident captured underlying tensions between citizens and security agencies.9

The Ejura tragedy highlights the deeply rooted systematic issues in the Ghana Police Service. The slow and suspicious police response to Kaaka’s death and disproportionate use of force against the protest constitute a security force in dire need of reform and investment. The violence which followed underscores the implications of low police pay, corruption, and weak institutions which work to erode public trust and fuel tensions. Kaaka’s activism was prompted by socio-economic issues typical of society whose customary support networks have disintegrated in modernization and market-based policies. In the absence of robust economic safety nets and functional state institutions for accountability, such unrest becomes increasingly feasible. The tragedy attests to the need for an integrated strategy which marries social protection with genuine investment in transforming policing.

Post Colonial Policing

Ghana vs Australia: Crime

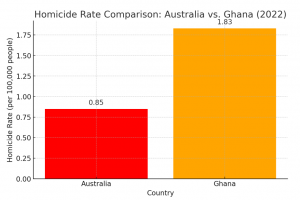

The following graphs provide an interesting contrast of the trends of crime between Ghana and Australia regarding homicide and incarceration rates. Please note that while Australia is not considered a post-colonial country, it does have post-colonial traits in the form of the injustice toward Aboriginal Australians. The first graph showsthat Ghana reported a significantly higher homicide rate of 1.83 for every 100,000 people in 2022, compared to the figure of 0.85 for 100,000 people in Australia. This suggests that violent crime as expressed in the number of homicides was more common in Ghana than in Australia. Several factors could account for the disparity, such as socio-economic conditions, the effectiveness of the police, crime-reducing programs, and the level of social conflict or organized crime.10</em>

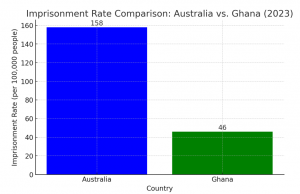

The second figure compares the 2023 imprisonment rates and shows a different trend. Australia’s incarceration was significantly higher, with a ratio of 158 prisoners for every 100,000 people, compared to a much smaller ratio of 46 prisoners for 100,000 people in Ghana. This disparity suggests that Australia has more severe legal punishments and a larger system of prisons in comparison to its population. Australia’s higher level of incarceration could indicate that the country is more punitive in its crime policy with more severe sentencing schemes, a higher level of offenses being prosecuted as crimes, or more reliance on incarceration as a method of deterrence.

Ghana’s low level of incarceration but high level of homicide displays several different implications: the police could have fewer offenses prosecuted, the justice system could rely more heavily on alternative justice mechanisms, or it could have more systemic issues such as a crowding of the prisons or lack of legal resources that result in fewer people being incarcerated. The contrast between these two nations raises questions about how nations respond to crime and punishment. While the homicide rate is lower in Australia, the higher imprisonment rate could result in more of a focus on police and prisons to deter or incapacitate more violent offenses. On the other hand, Ghana’s relatively low level of imprisonment with the higher homicide rate could reveal corruption in the justice system or culturally different attitudes toward crime and punishment. Both examples highlight the management of crime and justice policy is the result of a complicated mix of economic times, government, the effectiveness of the police, and social policy in the two nations.11

Post-colonial Economic Structures Effect as a Security Issue

Post-colonial economies have had a significant impact on security in Ghana, through the weakening of traditional social protection networks and increased reliance on policy-driven markets. Hitherto, the Ghanaian society drew on the extended family as the primary institution for social and economic security, with vulnerable members of society such as the old, unemployed, and disabled being taken care of. These traditional social protection networks unfortunately received a devastating blow with the implementation of economic policies involving the promotion of deregulation, divestiture, and adjustment in the 1980s. The creation of a policy-driven development policy of a market nature demoted the state’s intervention in economic affairs and forced a diminishing effect on the government delivery of social services and welfare. The process subjected people and households to great pressure to achieve economic security, with the result that vulnerability was even further aggravated. The breakdown of such traditional networks of social security consolidated economic insecurity and heightened social tensions, with the result that poverty and inequality became a rising security issue12

Despite economic progress in Ghana, the anticipated trickle-down effect has not materialized, and marginalization and poverty have risen in certain areas, most notably the north and the Central Region. The use of stabilization and adjustment policies, including the dismantlement of subsidies and elimination of wages controls, has led to the loss of jobs, rise in the cost of living, and widening of economic gaps. Despite the institutionalization of structures such as the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) to provide for a level of protection, these formal provisions often fell short, covering only a minority of the population and providing narrow protection. Noncompliance with international social security standards such as those embodied in the provisions of the Social Security Conventions of the International Labor Organization, and those of the provisions of ILO Convention 102, raises exposedness, with the majority being deprived of such elementary protection as access to health care, maternity allowances, and family allowances. Such a lack of widespread social protection poses a security risk to Ghana by fueling social tensions, crime, and poverty traps. Policies that prioritize economic development to the detriment of equitable social protection tend to encourage instability. A more equilibrium policy that integrates economic development with effective social safety nets is needed to facilitate long-term security, but is difficult to achieve.13

Since gaining independence in 1957, the police in Ghana have remained a centralized force, structured into several administrative regions, divisions, and districts. While an initial increase in the size of the police leading up to and immediately following independence occurred, the force since then reduced in size relative to the increasing population of the nation, with the result being a police-civilian ratio below the United Nations minimum. While post-colonial governments had been anticipated to bring about a change in the police force, in terms of its organization as well as its ideology, these hopes largely proved unrealized. Governments have continued to use the police as a means of suppressing political opposition in preference to being a neutral force to maintain law and order. Under the authoritarian regimes that characterized much of Ghana’s post-colonial period, the police frequently engaged in human rights abuses, arbitrary detention, and detention without trial. Despite the institution of the democratic government in 1993 through the Fourth Republic, hopes of an accountable and respectful police force have regularly been dashed. Police officers continue to flout constitutional provisions by detaining suspects longer than the 48 hours provided for by the law, with the weekends being used as a justification for detaining people without charging them. Corruption is also a deeply entrenched issue, with the traffic police being regularly accused of demanding bribery, with more serious allegations of collaboration with the more serious crime of the drug trade, as well as that of armed robbery. Investigations such as the Woode Committee of Inquiry have exposed serious professional misconduct among the highest echelons of the police command. Recruitment and promotion in the force have also been marred by nepotism and favoritism, helping to erode public confidence in the institution. Despite constitutional guarantees and occasional reforms, the Ghana Police Service is plagued by institutionalized issues that undermine its credibility and capacity to uphold the rule of law.14

Conclusion

Post-colonial economic structures on security in Ghana eroded traditional social safety nets, deepened economic inequalities and the challenges faced by law enforcement. While market-led economic policies have driven growth, they have also contributed to social vulnerability and crime, placing additional strain on the Ghanaian Police Service. Inadequate policing resources, combined with a weakened extended family system, have made it difficult to address the root causes of insecurity. To enhance national security, Ghana must adopt a balanced approach that strengthens social protection systems while improving the effectiveness, accountability, and community engagement of law enforcement. A comprehensive strategy that integrates economic stability with robust policing reforms can ensure long-term peace and security.

Key terms:

Big Push – This economic theory suggests that a significant initial investment in infrastructure and industry is necessary for sustained economic growth.

Resource Curse – The paradox where countries rich in natural resources experience slower economic growth due to mismanagement, corruption, and economic distortions.

Habitual Criminals List – A record of individuals repeatedly convicted of crimes, used by law enforcement to monitor and control repeat offenders. I

Woode Committee of Inquiry – A governmental investigative body tasked with reviewing and making recommendations on national issues.

Divestiture – The process of transferring state-owned enterprises to private ownership to improve efficiency and economic performance.

Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) – The primary public institution managing pensions and social security for formal sector workers in Ghana.15

International Labor Organization (ILO) – A United Nations agency that sets labor standards and promotes fair work conditions globally.

ILO Convention 102 – An international standard outlining minimum social security protections, including unemployment, sickness, and old-age benefits.

References:

Cynthia Agyiriwaa Asiedu, ‘Natural Resource Dependence and Economic growth in Ghana: the effect of Oil Production,’ International Institute of Social Studies, December 2017, Pages 6-12, Asiedu-Cynthia-Agyiriwaa.pdf

Tetteh A. Kofi, ‘Structural Adjustment in Africa,’ The United Nations University, October 2017, Pages 41-45 Structural Adjustment in Africa A Performance Review of World Bank Policies under Uncertainty in Commodity Price Trends: The Case of Ghana

Justice Tankebe, ‘Colonialism, legitimation, and policing in Ghana,’ International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 2007, Pages 68-80, doi:10.1016/j.ijlcj.2007.12.003

Country Economy, ‘Countries Data: Demographic and Economy,’ Country comparison Ghana vs Australia Intentional homicides 2025 | countryeconomy.com

Dr. Augustine Fritz Gockel, Prof. Kofi Kumando, ‘A Study on Social Security in Ghana,’ University of Ghana Legon, February 2003, Pages 1-15, Social Security in Ghana A Study by Prof Kumado & Dr. Goc…

Kumi E, 2020, ‘From donor darling to beyond aid? Public perceptions of ‘Ghana Beyond Aid,’ The Journal of Modern African Studies, From donor darling to beyond aid? Public perceptions of ‘Ghana Beyond Aid’ | The Journal of Modern African Studies | Cambridge Core

World Trade Organization, 2025, ‘Ghana and the WTO,’ WTO | Ghana – Member information

Aljazeera, 6th July, 2021, ”Ghana opposition supporters march against killings, lawlessness, Ghana opposition supporters march against killings, lawlessness | Protests News | Al Jazeera

- Kumi, E., “From donor darling to beyond aid? Public perceptions of ‘Ghana Beyond Aid,’” The Journal of Modern African Studies, 2020; 58(1), 67-90. ↵

- Addo, Kofi Odei. “British Colonial Rule: Its Impact on Police Corruption in Ghana.” International NGO Journal 17, no. 2 (November 30, 2022): 12–25. ↵

- World Trade Organization. (2022). Ghana. In World Trade Statistical Review 2022, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/ghana_e.htm#statistics retrieved on 3/24/2025. ↵

- Cynthia Agyiriwaa Asiedu, ‘Natural Resource Dependence and Economic growth in Ghana: the effect of Oil Production,’ International Institute of Social Studies, December 2017, Asiedu-Cynthia-Agyiriwaa.pdf ↵

- Cynthia Agyiriwaa Asiedu, ‘Natural Resource Dependence and Economic growth in Ghana: the effect of Oil Production,’ International Institute of Social Studies, December 2017, Asiedu-Cynthia-Agyiriwaa.pdf ↵

- Tetteh A. Kofi, ‘Structural Adjustment in Africa,’ The United Nations University, October 2017 ↵

- Cynthia Agyiriwaa Asiedu, ‘Natural Resource Dependence and Economic growth in Ghana: the effect of Oil Production,’ International Institute of Social Studies, December 2017, Asiedu-Cynthia-Agyiriwaa.pdf ↵

- Justice Tankebe, ‘Colonialism, legitimation, and policing in Ghana,’ International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 2007 ↵

- Aljazeera, 6th July, 2021, ”Ghana opposition supporters march against killings, lawlessness ↵

- Country Economy, ‘</span><em style=”font-size: 16px;”>Countries Data: Demographic and Economy ↵

- Country Economy, ‘Countries Data: Demographic and Economy ↵

- Dr. Augustine Fritz Gockel, Prof. Kofi Kumando, ‘A Study on Social Security in Ghana,’ University of Ghana Legon, February 2003 ↵

- Dr. Augustine Fritz Gockel, Prof. Kofi Kumando, ‘A Study on Social Security in Ghana,’ University of Ghana Legon, February 2003 ↵

- Justice Tankebe, ‘Colonialism, legitimation, and policing in Ghana,’ International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 2007 ↵

- Social Security and National Insurance Trust, Government of Ghana, https://www.ghana.gov.gh/mdas/bfdfe06ac0/ retrieved on 3/24/2025. ↵

24 comments

ysatake

This article is interesting by the point that reveals how post-colonial economic system had an effect on a wide range of systems including the security issue of present Ghana. In addition, this article highlights that to solve those issues and develop not only part of the country but also whole country, Ghana must reform deeply routed-system. From these implications, I have a question if there is specific solution for these issues, which provides well-balanced development between economic growth and long-term stability or security.

Rebecca Amaya

An unexpected fact I learned about Ghana’s security challenges is that in spite of its wealth of natural resources, its economic instability is still liable for its internal unrest and vulnerability to external threats. Its resource richness has added fuel to the flame in terms of corruption, inflation and unemployment. The point that resonated most was that Ghana’s youth has strong aspirations even in the face of limited opportunities. How can Ghana leverage its natural resources more equitably to foster long-term security and social cohesion?

Teagan McSherry

I was surprised to learn how deeply entrenched Ghana’s economic challenges are due to post-colonial structures, and how, despite gaining independence in 1957, Ghana’s economy remained heavily reliant on the export of a few primary commodities, such as cocoa and gold. Initiatives aimed at industrialization and infrastructure development demonstrate the country’s commitment to achieving sustainable economic growth, which resonated deeply with me. How can Ghana diversify its economy while preserving its cultural and environmental heritage?

Sarah

Thanks for an incredible article! I’ve always wanted to visit Ghana and learn more about this incredible place. Your article touches on many relevant ideas, such as the resource curse and public distrust of police.It strikes me that many of problems in Ghana need community oriented, bottom up solutions. People need to feel ownership over their home and empowered to improve it. In your research, did you come across any community led solutions where people have banded together outside of the context of the government to improve their security situation?

Alejandro Rubio Chappell

This piece really opened my eyes to how deep the effects of colonialism still run in Ghana. The story about the cocoa farmer in the beginning made the whole issue feel personal and real. I didn’t realize how things like structural adjustment policies and dependency on raw exports like cocoa and gold still hold the country back. The section comparing Ghana’s and Australia’s justice systems was also super interesting—especially how Ghana has higher homicide rates but lower incarceration, which says a lot about deeper systemic issues. The breakdown of the colonial police history and how it ties into current distrust in law enforcement tied everything together well.

Carollann Serafin

1) Learning about the two riches in the world Gold and Chocolate does not get more interesting and learning about how the exporting of materials really is. The Economic structures really impacted the country.

2) I was most interested in learning how this retakes to growing economically in ways you can especially when you do not have a strong structure to begin with I had not realized the social structures that were in place.

3) I would want to know your opinions and why you took an interest of studying this topic!

Cynthia Brehm

Why is Ghana outsourcing the processing of their natural resources? Despite being richly endowed, Ghana remains structurally dependent on the export of raw materials, many of which are sent abroad for processing. This practice not only limits domestic value addition, but also exposes the country to exploitation and systemic undervaluation. As Ahene-Codjoe, A, et al assert:

“Using Ghana’s top export commodities, gold and cocoa, we find that undervaluation in gold exports from Ghana amounted to 11% of its total exports. For cocoa beans and cocoa paste, we similarly estimated 1.0% and 7.2% respectively. We also estimated tax base erosion due to mispricing to be USD 957.3 million for gold, USD 31.6m for cocoa beans and USD 32.6m for cocoa paste during 2011-2017. Our findings thus suggest significant tax base erosion through trade mispricing from Ghana., it is neither sustainable nor strategically wise to entrust the processing of one’s most valuable assets to foreign entities” (Ahene-Codjoe, A, et al, 2021).

The belief that external partners will act in good faith without maximizing their own interest is, frankly, inconsistent with both economic history and human behavior. No nation that seeks to advance its economic sovereignty can afford to outsource the control of its wealth. Processing, refining, and manufacturing must occur within national borders if Ghana is to reverse the persistent outflow of value and dependency.

To reposition itself for long-term economic success, Ghana must commit to:

• Developing domestic refining and processing infrastructure.

• Building human capital for high value industries;

• Strengthening institutional oversight and transparency; and

• Restructuring trade policies to prioritize local beneficiation.

Without such measures, the cycle of external dependence will continue, and the aspirations of national self-sufficiency and inclusive development will remain elusive. Ghana possesses the resources and potential—what is required now is the political will and strategic commitment to internalize its value chain and chart a new course.

Bibliography

Ahene-Codjoe, A., & et al. (2021). Gold Related Illicit Financial Flow Threats and How to Mitigate Them: The Case of Ghana [Thesis].

Micaella Sanchez

I found this analysis deeply interesting in its connection between Ghana’s past and its current issues. The discussion on economic dependency and weakened social structures helped me understand how historical legacies continue to shape everyday realities. Recognizing the importance of integrated reforms that not only enhance policing but also strengthen protection, great job on explaining how these things can impact social issues and Ghana’s society.

TJ

I appreciated how the article traced Ghana’s security challenges back to its colonial economic structures and showed how dependence on cocoa gold and oil fuels inequality and crime. The section on the breakdown of traditional support networks made clear why social tensions flare when formal safety nets are weak. I also found the historical overview of policing under British rule enlightening, especially how that legacy still affects trust in law enforcement today. Overall it tied economic history neatly to current security issues.

Lashanna Hill

What was unexpected to me in learning about their security challenges was the rising crime levels due to poverty and social exclusion. The best part of the story that resonated with me was the explanation of their inherited economic post colonial structure. How they lack funding, inadequate resources, and the low pay that leads to corruption.

How has Ghana shown their resilience in commodities despite current security issues?