Throughout most of Roman history, both tangible and legendary, the Roman state has always been an expanding state with imperial tendencies, not out of aggression, but out of a necessary defense of the city, the government, and the Roman way of life. From the early founding of the city in the eighth century BCE to Emperor Hadrian in the first century CE, within those nine centuries, Rome expanded all around the Mediterranean Sea, coming to control the known Hellenistic world, or to the Romans, the civilized world that could threaten Rome. The period with the most rapid growth and expansion was the period of the Republic, which arguably turned the Republic into an empire quite early in the history of Rome.

The Republic’s expansion was always in the defense of Rome, and not the result of an expansionist agenda. The Romans not only used expansion to protect the city of Rome itself, but it also used a system of client states on its borders to provide further security for the Republic and, later, for the Roman Empire for some time. Rome’s foreign policy was the same as their defensive strategy of preemptive strike against their enemies before they could conquer Rome, justifying their actions with their history.

This defensive/expansionist strategy can be seen even in the very founding of the city, following the traditional story of Romulus and Remus. The twins, fathered by the God of War, Mars, as young adults, became bandits and preyed on other bandits. Later, after helping their human grandfather, Numitor, King of Alba Longa, regain his throne from their evil brother, Numitor gave the twins land to build a city for themselves as a gift. During the establishment of the city, Romulus killed his twin brother for crossing the wall that ran down the center of the new settlement. Romulus slew his brother in response, which justifies Romulus’s actions, so that when a foreign power invades his city, he had to commit fratricide and expand, naming the entire settlement Rome.1

Thus, in Rome’s earliest history, from the city’s founding, Rome was rightfully defending itself from invaders and expanding to mitigate any threats to Rome. However, with the violent start of the Roman state, and with this defensive mindset, the Romans acted in an imperial manner in all but name itself, starting a tradition that the Roman state continued for centuries to come.

In the first three centuries of Rome’s existence, from the kingdom to the successor state of the early Roman Republic, when the Roman nobles deposed the last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, in 509 BCE, the expansion of Rome was slow, almost passive. It is nothing like its more aggressive expansionist self that history is fonder of recording and retelling. Rome maintained its defense not through expansion but through alliances with other city-states and tribes, primarily with the Latins, just south of Rome. Slowly, the Roman citizens started to develop a concept called civitas, which, to the Romans, meant that every man had a stake in the state: they not only enjoyed times of peace and prosperity, but also bonded in times of fear and sorrow.2

This concept of civitas, and two significant events, changed the destiny of the Roman Republic and the Roman people. One incident occurred in the fourth century BCE, when an invading force of 30,000 to 70,000 Gallic Celts, known as the Senones, led by Brennus, descended on Rome. In response, Rome and her allies sent their armies to stop the Gauls; however, Rome’s and her allies’ combined armies were utterly destroyed at the Battle of the Allia.3

Shortly after the battle, the Senones marched upon Rome with such speed that Rome was not able to raise another army in time, and her people were forced to abandon the city. And if the legend is true, the politician who guided Rome into the war stayed behind to distract the Senones while the rest escaped, losing that day not just their homes, but also their wealth and leadership. The horror of that day would remain with the Romans throughout the Republic and into the early empire. The first sacking of Rome taught the Romans to be extremely defensive, raising armies whenever there was a possible threat to the city.4

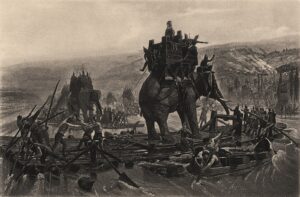

The first sacking of Rome would remain with the Roman citizens for generations. And the event that truly made Rome grow into the ancient superpower, one that ceaselessly expanded for centuries out of the defense of Rome, was the Punic Wars. It was during the Second Punic War, a war not against the ancient maritime and trading empire that was Carthage, but rather against one of the most famous sons, Hannibal Barca—starting with his attack on Roman Allies on the Iberian Peninsula, which, because it was an attack on Roman Allies, was also considered an attack on Rome herself. Then Hannibal led an expedition into the Roman heartland by crossing the Alps with over a hundred thousand men and forty elephants. And for sixteen years, the forces of Hannibal harassed the Roman countryside and crushed any Roman army sent to stop him.5

Hannibal terrified the Romans and their allies on the Italian peninsula for fifteen long years. It was only after Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus forced Hannibal out of the Roman heartland after his brother Hasdrubal was beheaded that Rome became somewhat safe again. He was later defeated in the Battle of Zama near Carthage. When the war against Hannibal came to an end, with over 600,000 casualties on both sides of the war, many Roman boys and young men would remember for the rest of their lives, how close they came to annihilation. That memory prompted the Roman senate to wage the Macedonian Wars and the Third Punic War to end Carthage as a Mediterranean power.6

These defensive wars were costly, not just in terms of resources and the lives of Roman sons and their allies, but in their very pride in Rome herself. For Rome almost fell more than once in its thousand-year history, because Rome was not able to react in time. And they would have fallen if the Republic did not have a massive reservoir of manpower at her disposal. The Roman Senate believed that the only way to defend the Republic was to expand its borders, annexing the lands of the Carthaginians and the Macedonians, almost doubling the size of the Republic. The Romans also gave lands to their allies, which they later conquered in the years to come, for they too could have become a threat to Rome.7

This strategy of expansion and protection gave Rome vast amounts of manpower and resources. Rome was able to deploy her forces in a timely manner to protect the empire from threats from foreign barbarians to rebellious governors and generals. The Roman legions had only two modes of transportation: either by roads, which could take months to go from one edge to the other, or by sea, which would take a much shorter amount of time, but could be just as dangerous due to the unpreparedness of the Mediterranean Sea in winter, leaving a narrow window for safe sailing. The Republic and later the early empire expanded the military, gave the provinces greater freedom in raising their own armies or in outsourcing the defense of Rome to client states.8

Due to Roman Law, only Roman citizens could join the legions, which also limit the rate of expansion, while subjects of the empire were limited to joining the auxiliary units. The Roman government felt uneasy with provinces having the ability to raise an army and thus possibly rebelling against Rome itself. So, that left a system of client states for the defense of the borders and Rome. Most of these client states would be founded on the eastern and northern borders of the Roman State.9

Most of these client states were not just a means to buffer the Roman borders from outside threats, excluding that of Armenia, separating Rome from the Parthian Empire in the East, a successor state of the Persian Empire from Roman territory. For the most part, these client states, which were semi-settled centralized tribes and kingdoms, were a means to project Roman power into the neighboring unruly tribes. But also, the main purpose of these client states were to handle low to medium-intensity threats, while slowing down greater threats to Roman security, in order for Rome to respond with their own forces, while they [the client state] provided military, material, and economy support to Rome.10

This system benefited the early empire greatly, for with the ability to only raise at best twenty-five to thirty legions and thirty auxiliary units, Rome was able to maintain security across the 7500 kilometers of the frontier border. And with natural geography, some regions of the frontier did not require a client state for security, such as in Northern Africa, with the Atlas Mountains and the Sahara serving as protection. Garrisons could be placed in key oases and trade routes to keep the southern frontier maintained. Yet the desert still would not stop the Romans from exploring and settling in the Sahara and beyond.

The client states and the natural barriers not only allowed Rome to maintain border security with a surprisingly small military, but also it allowed Rome to redeploy from one part of the empire to another without leaving a vacuum of military power in any region. This system allowed Rome to deploy legions from one part of the empire to another, to deal with high intensity threats, either external or internal. One such was the Third Servile War, or as Plutarch calls it the War of Spartacus, in 73-71 BCE. This war required eight legions to be pulled from the border to the Roman heartland to put down the rebellion.11

Other such examples of Rome being able to pull legions from other regions of the empire would be when they partly conquered Germania, modern day central Europe, but were stopped when they lost three legions in the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE. And minus the shame that Quincilius Varus felt, causing Augustus to lose his composure, “he let the hair of his head and beard grow for several months, and sometimes knocked his head against the door-post, crying out, ‘0, Quintilius Varus! give me back my legions!’ And ever after, he observed the anniversary of this calamity as a day of sorrow and mourning.”12 Even after losing three legions—and a typical Roman Legion size would range from five-thousand to six-thousand men, a sizeable force—the empire did not experience significant security threats that were caused from the loss of the legions in a single campaign.13

Then later, in 43 CE, Rome finally conquered the island of Britannia, turning it into the farthest frontier of the Roman Empire.14 But a state cannot expand forever. Soon the Roman Empire reached its zenith in the second century under the role of Emperor Trajan. The empire no longer had the resources to wage an offensively defensive war against threats outside the frontier borders. During the reign of Emperor Hadrian, he not only ending the war with Parthia and closed off the frontier, ending Rome’s policy of defense through conquest and turning the Roman legions into tools of conquest and into a security force, which did bring some benefits to the empire, such as legions being placed in more permanent positions along the border. This ended Roman expansion, with its mobile armies roaming the empire, and with the government taking a direct rule over their provinces and their client states. Thus, ended the golden age for Rome, for from the second century onwards, Rome faced many challenges from within the empire, causing the power of Rome to wane, and led to its eventual fall, giving way to the dark age and the rise of Constantinople and it empire.

- Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 1, Chapter 7, translation by William Heinemann (London: Harvard University Press, 1919), 40, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0151%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3D7. ↵

- Eric Adler, “Post-9/11 Views of Rome and the Nature of ‘Defensive Imperialism,’” International Journal of the Classical Tradition 15, no. 4 (2008): 587–610. ↵

- Peter Berresford Ellis, Celt and Roman : The Celts of Italy (New York : St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 10. ↵

- Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 5, Chapter 38, translation by William Heinemann (London: Harvard University Press, 1919), 491, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0151%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3D7. ↵

- Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 21, Chapter 31, translation by William Heinemann (London: Harvard University Press, 1919), 51 http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0151%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3D7. ↵

- Historia Civilis, The Battle of Zama (202 B.C.E.), 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjxYJBWcS08. ↵

- Mark Cartwright, “Second Punic War,” World History Encyclopedia, 29 May 2016, https://www.worldhistory.org/Second_Punic_War/. ↵

- Edward N. Luttwak, “The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire,” The John Hopkins University Press (January 1, 1979), Baltimore, and London, 24. ↵

- Michael A. Speidel, “Legal Status of Roman Soldiers,” ed. C. Schmetterer, The Classical Review 64, no. 2 (2014): 547–49. ↵

- Edward N. Luttwak, “The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire,” The John Hopkins University Press (January 1, 1979), Baltimore, and London, 25. ↵

- Joshua J. Mark, “The Spartacus Revolt,” World History Encyclopedia, accessed November 8, 2022, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/871/the-spartacus-revolt/. ↵

- “C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Divus Augustus, Chapter 23,” (Gebbie & Co. 1889), 155. ↵

- Jonathan Roth, “The Size and Organization of the Roman Imperial Legion,” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte 43, no. 3 (1994): 347. ↵

- Paul Pattison, “The Roman Invasion of Britain,” English Heritage, November 11, 2022, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/richborough-roman-fort-and-amphitheatre/history/invasion/. ↵

25 comments

Abbey Stiffler

Congrats on your nomination! I had heard the tale of Romulus and Remus before, it had never been told in the way that the author did. I liked how Rome would protect their empire through expansion and conquest of as many nearby empires, which in the short term would result in the loss of many of its citizens to war but would improve its security in the long run.

Kristen Leary

Congratulations first of all to having your article nominated for an award! There is so much that can be said about Rome, so I’m sure there was lots of sources to go through to find what was relevant to your topic. Great job on doing good research to produce such a good article! It was an interesting topic presented in a very informative way.

Luke Rodriguez

This was a fantastic read! Also, congrats on the nomination! It was well-deserved. The article was well-written and detailed. This was a well-structured article, and I truly enjoyed reading this. The defensive mentality ingrained in Roman culture from its inception appeals to me. The article articulately details how expansion bolstered Rome’s defensive capabilities while also contributing to the prosperity of the Roman Empire.

Brandon Vasquez

Seth you did a fantastic job with this article. I have been very interested in Roman history and how they ran their republic and empire and this article did a great job of giving me a different point of view for the expansion of Rome. Without such expansion it would have definitely made it harder for the empire to survive.

Lyle Ballesteros

I really enjoyed this article. It was really informative and I appreciated the amount of detail you went into regarding Rome and how they defended their empire. I enjoyed how ROme would defend their empire by expansion and defeating as many empires that were near them which in the short term would lose many of their people in war but would help their safety and how many resources thay had in the long term.

Carina Martinez

You did a great job on this article! Congratulations on your hard work. It was very seamless although covering an extensive historical background. Despite all the information, this article was a great read.

Marissa Rendon

This article was a very educational article to read. Many Senones changed the history as well as Rome’s army. The defensive plan Rome used was really interesting to read about. I liked how descriptive the article got about Rome and the history behind them.

Guiliana Devora

This was an amazing article and the author did an amazing job of telling it! To learn about the history of Rome and some of the events that happened is incredible to me. It is crazy to think about all that has happened on this earth and how much countries have changed dealing with things. Also on the other hand, there is the aspect of countries still having the same desires just as they did centuries ago. I feel as though some desires and ways will never change.

Jacqueline Galvan

I felt that this article was a thorough explanation of Rome’s defensive system. The author brought up a viewpoint that I have never even thought to explore, one that describes Rome’s expansion not as an act of violence, but as a necessary act to survive and thrive. I had heard the story of Romulus and Remus, but never in the way that the author described. Overall I very much enjoyed this take on such an important piece of history.

Danielle Sanchez

Congratulations on your nomination! This article was well written and informative! From the early founding of the city in the eighth century BCE to Emperor Hadrian in the first century CE, within those nine centuries, Rome expanded all around the Mediterranean Sea, coming to control the known Hellenistic world, or to the Romans, the civilized world that could threaten Rome.