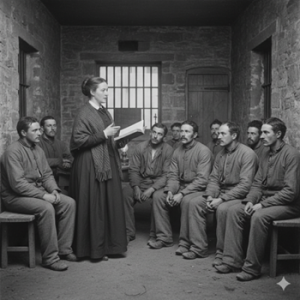

It was just another day of work when Dorothea Lynde Dix first volunteered to teach Sunday School at the East Cambridge Jail in Massachusetts in 1841. The cold bit at her cheeks as she walked through the dim corridors, trying to stay warm, but the scene in front of her made her forget about her own discomfort. Prisoners were chained to stone walls, shivering in the cold with nothing but rags for clothing. Some lay on the ground without beds, others huddled in corners for warmth. 1 Breathing became harder as she smelt the stink of unwashed prisoners. She was horrified by the treatment of these obviously neglected people. They had not even been given a fire to warm them on this cold winter day. As she looked further at the faces of these ill-fated people, she realized that they were, in fact, not criminals. They were people being punished for sicknesses that they could not help or change. They were people punished for their mental illnesses.

Although originally she was only there to teach the prisoners, at the sight of these poor victims, she knew that she needed to help them. A fire stirred in her heart while she watched a man huddling in his cold cell without fire or blankets. Although Dix was not formally educated on mental illnesses, she knew that no human being deserved to be treated in such a way. Moreover, they were people who had done nothing truly wrong except be sick. If someone else would not advocate for these people, then she would. This discovery marked the turning point in her life. The experience started Dix’s mission to investigate and improve how individuals with mental illnesses were treated throughout Massachusetts, and later on throughout the United States.2

Dorothea Dix’s early life shaped how she saw these prisoners. Her own mother, Mary Dix, suffered from continual illnesses, which led to emotional instability. Family life was hard, and Dix was forced to do a lot of the housework.3 Because of this, Dix understood what it was like to be the oldest daughter in this situation. She was forced to mature faster and take care of her siblings, but she also recognized that her mother needed to be taken care of and loved.

Her next experiences helped her appreciate having her own opinions and not going with what society expected of her. In her teenage years, she lived in Boston with her grandmother. Her grandmother was a respected woman who taught Dix how to be a member of intellectual and social groups.4 She learned to be a part of the social circles and how to talk to educated people. This was important for Dix because it allowed her to understand that part of society and how to create a name for herself. However, she clashed with the strictness of her grandmother’s rules. She saw how different the people were from her original life with her parents and siblings. She also saw the things that they were passionate about and worked for, which was something that she longed for in her own life.

Nevertheless, her time with her grandmother allowed her to open a school in Boston by the age of nineteen. This was a great accomplishment for someone so young, and she set about making the school her own. She highlighted the importance of intellectual intelligence over memorization. She understood that true learning was not merely the memorization of isolated facts but the cultivation of intellectual intelligence. It was a deeper comprehension of the world and the intricate connections that bring those facts together to form understanding and insight. This was different from most schools at the time, and it showed her ability to think critically and act morally even when it went against the norms of society.5

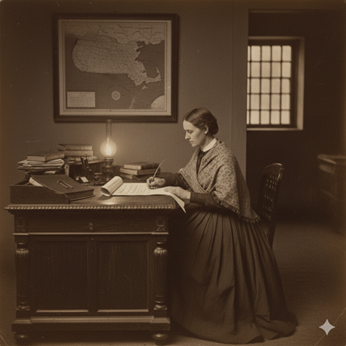

These early life experiences created a foundation to help Dorothea Dix persevere in her efforts of reform. Her teaching made it easy for her to talk to others and expand upon her reasoning, and her writing gave her the intellectual vocabulary to portray her insights in an academic setting, both of which gave her the confidence to speak publicly and advocate for others, something that most women at the time did not possess.6

After that fateful day in the prisons, Dix wondered if it was only East Cambridge Jail that was treating its mentally-ill prisoners in such a way. To accomplish this, she decided that it was vital that she investigate the other prisons around the area. While she started her journey to the prisons with hope in her heart that there she would not find the same treatment, that hope slowly dwindled. Everywhere she went, from prisons to almshouses, she found appalling conditions. People with mental disorders were confined in cages, left chained to walls, or even naked in unheated rooms. When Dix tried to advocate for blankets or a fire, the head of the prison would argue that it would be a safety risk to allow these deranged people access to a fire, even though they had nothing else to keep them warm.7 Many of these people were innocent of any crimes. The prisons took these people who were unwanted by society or were simply found confused on the streets and subjected them to even worse conditions. Dix could relate to that hardship because of the difficulties she had faced when taking care of her own mother, but she still knew how wrong it was to confine these people with such treatment.8

Dix’s investigations touched on the broader issue of criminalization of the mentally ill in the nineteenth century. During this time, most prisons were used as a place to put the unwanted, where those deemed unfit for society, including the mentally ill, were simply locked away rather than treated. Society at the time did not have a proper understanding of mentally ill people and their needs.9 So, while the United States prison system was undergoing changes to help with the treatment of prisoners, it did not include the changes that were needed in medical care.10 In this place, people with mental illnesses were left without protection or dignity.

Dorothea Dix wrote a memorial to the Massachusetts legislature begging for reform. In it, she described the horrible conditions of the prisoners in detail. She wrote how improvements of these establishments and treatments were crucial to society. Her memorial shocked the public and stirred debate in the Massachusetts legislature. Through it, she was able to gain the support of two politicians: Horace Mann and Governor John Davis. This was crucial to her work, as while Dorothea was educated and a teacher, she was not a politician, and without these two people’s support, she may have never been able to continue her mission. With their help, however, she could better work to convince Massachusetts lawmakers of the need to reform these prisons. Eventually, Dix succeeded in persuading lawmakers to expand the State Lunatic Hospital at Worcester to house more patients and improve facilities. The Massachusetts legislature eventually approved funds for the first state mental hospital, which was just the beginning of Dorothea’s spread of influence across the country.11

Dorothea realized that this would not be the end of her mission. While her early experiences in the East Cambridge Jail ignited a moral reform in the prisons of Massachusetts, there was still the rest of America that needed reform. So Dorothea decided to travel to New Jersey to investigate the prisons there. The other state prisons were still in states of disrepair and inhumane treatment of their mentally ill patients, with no one advocating for their reform. Dix had always known that these people should not be put in prisons at all, but at the time, there was nowhere else for these people to go. There needed to be a safe haven for these people.12

During her time in New Jersey, she worked continually for not just better treatment in the prisons but also for public asylums. This would allow people without money or access to help to still be able to be properly treated for their illnesses. This would require funding as well as state legislative improvements. Dorothea continued to write memorials to the state legislatures and lobbied for social and moral reform that this change would require. It had been seven years since that fateful day at the East Cambridge Jail, and still, there was yet to be an asylum opened for these people that she worked so hard to protect.

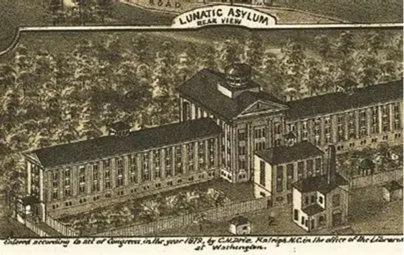

Then, finally, in 1848, there was a breakthrough. The culmination of Dorothea Dix’s years of tireless investigation and advocacy arrived when the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum in Trenton officially opened its doors. As the first public asylum in the United States, it was a landmark achievement. Nevertheless, it was more impressive that it was a direct result of Dix’s advocacy. It clearly showed that her strategy of investigation, moral reform, and appeal to the legislature could create lasting change and improve society for these vulnerable citizens.13

The new hospital at Trenton embodied Dix’s vision of humane treatment for the mentally ill. Unlike the jails and almshouses where the people were chained like prisoners in cold cells, the asylum provided its patients with medical attention, warmth, and kindness. It supplied the patients with space, outdoor gardens, and windows. This showed how this was not a form of punishment but instead a haven for these people.14 The success of the Trenton institution demonstrated that mental illness could be treated with compassion and structure, rather than confinement and shame, which was a revolutionary idea at the time.15

By the close of 1848, Dorothea Dix was no longer just a Massachusetts teacher or a local advocate. Instead, she had become a national reformer and was known in nearly every statehouse as the advocate for the mentally ill.16 It was proof that her methods worked and moved both public officials and private citizens to take note of America’s forgotten citizens.17 She had transformed that day at the prison into a political action.

After the success of the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum in 1848, Dorothea Dix wasted no time using it as a model of reform. In speeches and memorials, she pointed to the Trenton asylum as proof that humane treatment of the mentally ill was both possible and effective.18 She argued that if New Jersey was able to accomplish this, then other states could follow suit. This led to more laws being passed as well as asylums and hospitals being built in North Carolina and Illinois in the next three years.19 She started campaigns in Pennsylvania and Maryland to strengthen support for state-funded hospitals. Her persistence inspired local reformers and helped unify mental health efforts across state lines.20

By the early 1850s, Dorothea Dix had become the catalyst behind America’s improvement in mental illness reform. What began in one Massachusetts jail had now spread across the nation, reshaping how the government and public thought about America’s forgotten citizens and establishing a more compassionate society.12

I would like to thank my fellow classmates at St Mary’s for helping me stay focused on this project. I would not have been able to finish this project without their continuous encouragement throughout the semester. I would also like to thank Dr. Whitener for his assistance in each stage of the project, especially when I was struggling with my research and citations. I am so grateful for this opportunity to be a part of this project, and I know that I will be forever grateful for all it has taught me.

- Sonya Michel, “Dorthea Dix; or, the Voice of the Maniac,” Discourse 17, no. 2 (1994): 52-53. ↵

- Margaret Muckenhoupt, Dorothea Dix: Advocate for Mental Health Care, Oxford Portraits (Oxford University Press, 2003), 42. ↵

- Margaret Muckenhoupt, Dorothea Dix: Advocate for Mental Health Care, Oxford Portraits (Oxford University Press, 2003), 11-12. ↵

- Margaret Muckenhoupt, Dorothea Dix: Advocate for Mental Health Care, Oxford Portraits (Oxford University Press, 2003), 13; Susan Hayes, “Dorthea Dix (Women’s History Month),” Times-Mail, The (Bedford, IN), March 17, 2005, NewsBank (14770F77EA9C8DD8): 1. ↵

- Margaret Muckenhoupt, Dorothea Dix: Advocate for Mental Health Care, Oxford Portraits (Oxford University Press, 2003), 15-16. ↵

- Sonya Michel, “Dorthea Dix; or, the Voice of the Maniac,” Discourse 17, no. 2 (1994): 53. ↵

- Margaret Muckenhoupt, Dorothea Dix: Advocate for Mental Health Care, Oxford Portraits (Oxford University Press, 2003), 43-44; Michael J O’Sullivan, “Criminalizing the Mentally Ill,” America 166 (December 1992): 9. ↵

- Matthew W. Meskell, “An American Resolution: The History of Prisons in the United States from 1777 to 1877,” Stanford Law Review 51, no. 4 (1999): 848–849. ↵

- Michael J O’Sullivan, “Criminalizing the Mentally Ill,” America 166 (December 1992): 8. ↵

- Matthew W. Meskell, “An American Resolution: The History of Prisons in the United States from 1777 to 1877,” Stanford Law Review 51, no. 4 (1999): 852–853. ↵

- Margaret Muckenhoupt, Dorothea Dix: Advocate for Mental Health Care, Oxford Portraits (Oxford University Press, 2003): 51; Susan Hayes, “Dorthea Dix (Women’s History Month),” Times-Mail, The (Bedford, IN), March 17, 2005, NewsBank (14770F77EA9C8DD8): 1. ↵

- David L. Gollaher, ed., The Historian 58, no. 4 (1996): 842. ↵

- Margaret Muckenhoupt, Dorothea Dix: Advocate for Mental Health Care, Oxford Portraits (Oxford University Press, 2003), 56. ↵

- Sonya Michel, “Dorthea Dix; or, the Voice of the Maniac,” Discourse 17, no. 2 (1994): 60-61. ↵

- Michael J O’Sullivan, “Criminalizing the Mentally Ill,” America 166 (December 1992): 11. ↵

- Sonya Michel, “Dorthea Dix; or, the Voice of the Maniac,” Discourse 17, no. 2 (1994): 62. ↵

- Margaret Muckenhoupt, Dorothea Dix: Advocate for Mental Health Care, Oxford Portraits (Oxford University Press, 2003), 64; David L. Gollaher, ed., The Historian 58, no. 4 (1996): 56. ↵

- Sonya Michel, “Dorthea Dix; or, the Voice of the Maniac,” Discourse 17, no. 2 (1994): 64. ↵

- Susan Hayes, “Dorthea Dix (Women’s History Month),” Times-Mail, The (Bedford, IN), March 17, 2005, NewsBank (14770F77EA9C8DD8): 1. ↵

- Michael J O’Sullivan, “Criminalizing the Mentally Ill,” America 166 (December 1992): 12. ↵

- David L. Gollaher, ed., The Historian 58, no. 4 (1996): 842. ↵

4 comments

Briana Ortega

I learned a lot from this article, it helped me understand how empowering Dorothea Dix’s work was and how it all began with just one visit to a jail. I thought that the descriptions of the cold, dark conditions and how those who were mentally ill were treated showed the sad reality of many, and it made me feel sympathy for those people. I enjoyed learning about her background and how her childhood shaped the woman she was and her compassion for others. It also showed how determined she was, especially when she kept traveling and writing to lawmakers to make a change. Overall, this article really showed how one person can make such a great difference through care and persistence.

Darryl Klein

It’s an inspiring story when someone sees an injustice and takes clear, decisive action to correct it. That powerful call to do what’s right resonates with a us. Last weekend, we were in Atlanta, and the scale of homelessness there is a stark reminder of the needs in our own communities, especially as the seasons turn. What’s particularly troubling is the human element behind these numbers. Data from Atlanta shows that almost half of the adults experiencing homelessness have a serious mental illness, highlighting a major crisis of care. These are our neighbors who are dealing with profound challenges, and the lack of housing only makes their struggle worse.

This situation isn’t unique to Atlanta; the struggle of homelessness, complicated by mental health issues, is a national problem—and it exists right here in America. Thank you for bringing the issue to the forefront with your rendition of Mrs. Dix.

Thomas Krol

I enjoyed this excellent short summary. I learned some things that I was not familiar with . It is a good reminder that we need to bring back our mental health hospitals to help care for these forgotten people

Mary Jo Klein

Excellent article! A well-researched examination of an important advocate for the rights of the mentally ill.