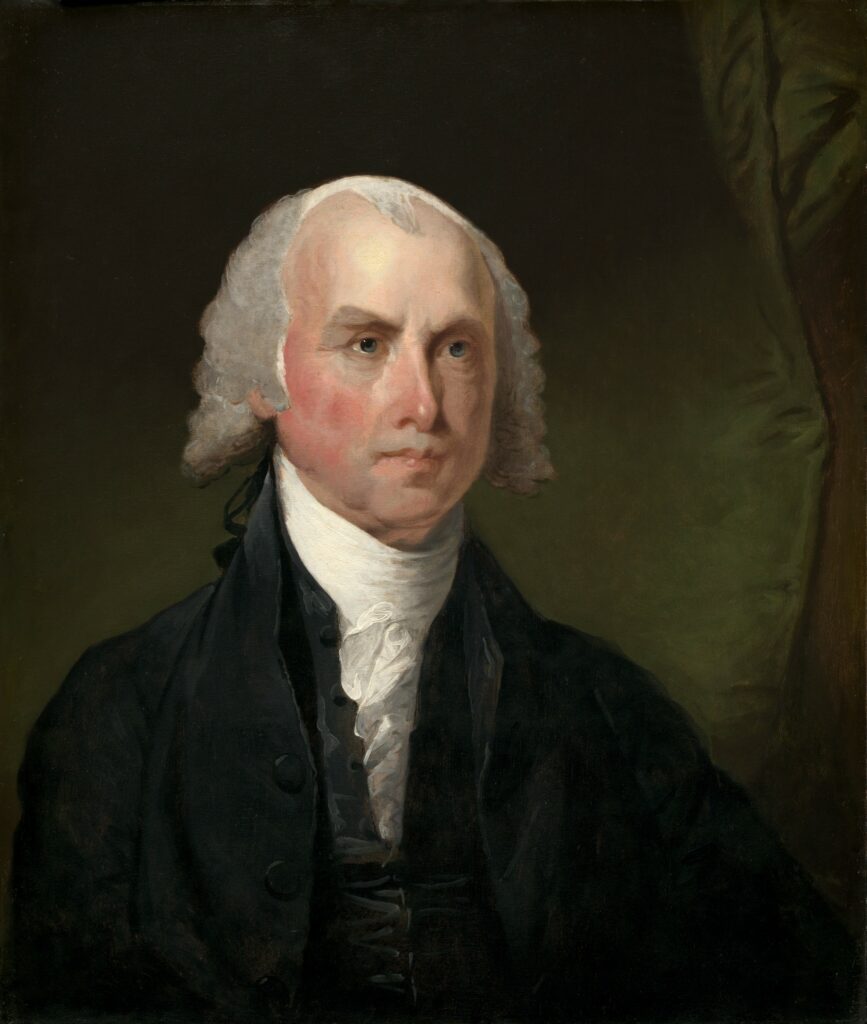

Statesman, Founding Father, and the 4th president of the United States of America. The man who is remembered as the author of the U.S. Constitution had to face a difficult question when drafting the document: how would the reimagined government of the young USA be able to balance the tyrannic forces of the majority and the minority, as seen in the problems of pure democracy and pure monarchy? In order to see how he answered that question, we need to analyze Madison’s thinking up to the point of his writing it, looking into his educational background, his varied experiences in government, and his own reasoning while drafting the Constitution and interpretations of that reasoning. His solution was to create a division in the authority of the government, using the separation of powers to keep the government from becoming too centralized to be ruled by any form of tyrant, whether in the form of a mob or a would-be dictator, but to also separate those in government from each other to prevent it from becoming a singular controlling entity.

Madison Before Revolution

To begin analyzing someone’s political philosophy, one can start at the beginning. As we will soon discuss, Madison’s early experiences and educational background are critical for deciphering how he began to develop his adult image and philosophy. James Madison, born on the 16th of March, 1751, was just 1 of 12 children to James Madison, Senior, and Nelly Conway. Being born on the Belle Grove Plantation in Conway, Virginia, and having been surrounded by most of the elites in the area through ties to his family, his upbringing ensured that he was forever exposed to Virginian politics. His father, a prominent tobacco planter in Piedmont, granted the young Madison a comfortable lifestyle for the era, where at the age of nine, he and his family moved to Montpellier. As Madison grew old enough to go to school, he excelled and was sent to college in 1769. During his time at university, he met and befriended John Witherspoon, who was Headmaster of the College of New Jersey at the time, though it was later renamed to the now recognizable Princeton University.1 Madison’s friendship with Witherspoon imbued him with a passion for reading and learning, even taking an extra year to learn both Law and Philosophy, and becoming the school’s first graduate student in 1771.2

When he returned home from university the following year, Madison became involved in his local government, learning and developing his political image. During this time, he was exposed to the persecution of the Baptists by colonial Anglicans over religious differences. Incensed by this, he began to advocate not just for the toleration of the Baptists, but for religious toleration across the board, calling the act itself “that diabolical, hell-conceived principle of persecution” in 1774. Despite his advocacy failing to yield the results he was looking for, his experience made protecting religious expression a valued and almost core principle of his. While he himself was not part of an organized religion—Madison was a Deist—he began to expand his political horizons, having seen the tension between the colonies and England, and recognized the similarities he saw between that and the situation of the Baptists.3

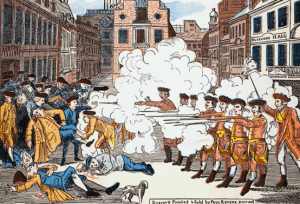

During the tense period before the Revolutionary War, a few developments had occurred. Two political camps came around: the Whigs and the Tories. Put simply, the Whigs were advocates of radical colonial rights, and developed into the Patriot faction seen during the war, while the Tories were those that were advocating and defending the colonial treatment from Britain. While not unsympathetic to the colonial plight of the era, the Tories held the position of negotiating with England rather than considering secession. Madison solidly placed himself as a Whig, worried that the King or Parliament was at risk of giving themselves the ability to remove the rights of the colonists without any sort of pretense or negotiation, as he believed that the colonies were not properly represented in the British Government and therefore had no political capability to properly object. When the Boston Tea Party occurred on December 16, 1773, and the British Crown responded with the Intolerable Acts, Madison further became involved directly with the developing Patriot faction and sided with the colonies into the coming war.4

Madison and the Constitution

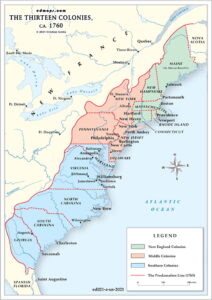

During the Revolutionary War, a government had been established, not only to represent the unified colonies, but also to have a centralized face and a visible sovereign or otherwise powerful figurehead to allow for negotiation between the colonies themselves and other countries, including countries like France, who helped finance the revolution in the first place, having provided them with supplies, men, and leaders. That initial government was articulated in the Articles of Confederation, and it lasted from its ratification in 1781 to its replacement by the U.S. Constitution in 1787. The Articles of Confederation, henceforth noted simply as the Articles, was a system of government that resembled the nature of the initial political ties of the colonies. In other words, it was merely a voluntary agreement between the colonies to act as one in matters of foreign affairs and war, but with no central authority that could act contrary to the unified voice of each member state. While this was strong in moral and cultural identity, and sounded off the central themes of liberty and freedom that the war became known for, it stressed the fragile relationships between the states unless something was done, since, among other things, any decision made through the Articles needed unanimous support, with all 13 colonies all agreeing on any decision, with no dissent. The problem many legislatures and government officials had was that the states did not act as one outside of what they had initially agreed to when ratifying the Articles. This meant that, in part due to the extremely limited government authority that was set up, the standing army could not be fed, taxes could not be collected, and the debt that the government owed was never paid off in any effective measure. As the war ended and things settled between the British and the States, internal troubles brewed, with a recession by the year 1787.5

In May of the same year, 55 delegates had been called to discuss the best course of action moving forward in Philadelphia. This became known as the Continental Congress, and it was a privately held meeting between these delegates under the pretense of simply reworking and strengthening the Articles. However, it became clear to the delegates that the current setup of the Articles was simply inadequate, changing the direction of the Congress from modifying the Articles to drafting an entirely new form of government.6 Madison is considered today as one of the key people scheduling the Convention, which occurred on the 25th, before which Madison spent months researching all manner of prior governments, most importantly confederacies and republics. Coming to the proverbial table with a plan, Madison, George Washington, and Edmund Randolph, the governor of Virginia at the time, jointly wrote up and proposed the Virginia Plan, a new form of government that attempted to rectify many of the issues that came with the Articles. The main setup of the plan he proposed included clauses that separated Congress into two separate houses, each with a proportional amount of representation based on population, the separation of authority held by the government into 2 main branches, along with enumerating a concise but varied amount of power and responsibilities to congress and the executive branch that they acted on, but not expand. This plan is considered today to be very favorable to a larger, more active government, and due to the widely varying populations of each state, had also been pointed out during the convention to have been partial to larger states as their larger population garnered more representation in the legislature. This preference, along with other complaints, had resulted in the plan being very strongly contested, with the main worries being the underrepresentation of smaller states and potential overreach by the new government into the affairs of the states.7

Other solutions were introduced on the floor of what is now known as Independence Hall, where Madison had one major competitor to his plan, the New Jersey Plan. Promoted and defended by William Patterson, this plan lay directly in opposition to the Virginia plan on several fronts. First and foremost, the New Jersey plan was designed to retain the current form of Government under the Articles. Among other differences, this plan held a one-house legislative branch that had the authority to elect a president, where each state was set with equal representation. More akin to the original aim of the convention, the plan was written to add powers to the Articles and increase the effectiveness of the government and legislature in response to the problems and needs of the day. For several weeks, the debate between each of the proposed plans occurred, drafting agreed components into a final document.8 Madison was held responsible for writing up the draft, and his negotiation abilities resulted in the Virginia plan having made a strong appearance in what became the Constitution. The final draft had a layout utilizing the strengths of each plan. To make it relatively even in the representation between states, the legislative branch had been designed to have 2 houses, the Senate, where each state would have 2 votes, and the House, where votes were set to be based on population. Built on three branches of government, each branch had some oversight on the other two, ensuring that no branch could exert absolute authority.9

Federalist Papers and Ratification

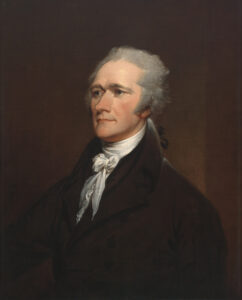

Once the final draft of the Constitution was prepared, it needed to go through a rigorous ratification process. While not every state needed to approve of the document, the 55 delegates had spread across the new states and attempted to persuade each local government to ratify the new setup. Madison worked in collaboration with John Jay and Alexander Hamilton on the writings of the Federalist Papers, a series of short-form essays meant to detail the logic and philosophy guiding the Constitution’s framing, making these documents ideal in trying to discover what made the Constitution so resistant to corruption early on. Madison is credited for writing Federalist Papers 10, 14, 18-20, 37-58, 62-63, with papers 18-20, 50-52, 54-58, and 62-63 being theorized to have been co-written with Hamilton. The most cited and referenced today are papers 10 and 51, and those will be the focus of our analysis.

Federalist 10 is addressed to the people of New York under the name Publius, as all of the papers were written under that pseudonym. This paper went over the problem of factions. Factions, as Madison described them, were

“a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.”

To break this down, a faction refers to any group of people, no matter how big or small, that are working together under a similar desire or goal that is somehow going to infringe on either the rights of other citizens or the goals and values of the community. He wrote on to detail that since these factions can cause great harm to what nation they hail from, there is a need to figure out what to do with them. He put forward two ways to deal with factions: one would be to cut off their ability to form, and the other is to limit their ability to do harm. He completely rejected the feasibility of the former, noting that while one can remove faction entirely, the methods of doing so was either suppressing their ability to form from the top down or “giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests,” and concluded that either solution had the guarantee to yield disastrous long-term results.

To suppress a faction’s ability to form, Madison theorized that to do so by either method, the resulting tyrant had to suspend liberty, which he deemed as “essential to political life,” and must be preserved. The other method, by having every citizen start with the same perspectives, was an impossibility in the eyes of Madison, since as long as the reasoning of a person can be considered fallible, there will always be a dissenting opinion or idea, which is what is needed to start a faction. We can begin to see Madison’s large distaste for tyranny in any form here, as he tries to convince people that the Constitution would protect the rights and sovereignty of everyone, not just the majority or the minority.10

Another paper we’ll look at is Federalist 51, and this is where we see what Madison’s vision was for how the federal government should deal with tyranny on the other end, and the concentration of authority and power held by a small group of individuals. His key concern about any government is that when making a government, “you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.” His answer to this conundrum turned out to be similar to what Baron de Montesquieu had theorized, that through splitting the powers of governance among the various branches, one can limit the potential effects of corruption from each of these branches. Madison proposed in the paper that a government should be split into several departments that are not dependent on each other, and that appointments to each of these departments should also be done separately from each other through the people. In relation to Federalist 10, Federalist 51 (hereafter noted as Fed 51) built on the idea of factions, and getting caught between trying to navigate the best for as many people as possible. The tonality of his writing has sent a subtext against absolute majorities, as if he did not want to have the new country become a democracy, and feared the threat of a majority rule that could gain the resulting authority to infringe on the rights of the minority, and then centralize the power to maintain control. However, the problem with simply centralizing authority is that a minority can begin to infringe on the rights of the majority, so long as they place the right people in the right place. By having attempted to separate each branch, and tried to ensure that the only overlap seen is considered absolutely necessary and minimally implemented, Madison expressed a goal to try to limit control from as many possible influences and restrict the consequences of what remains, and that has appeared in many of his actions and policies, a very matured and traditional view that control is like an illusion or a fantasy, that which does not exist in the form one commonly desires, but through trying to attain it, one begins to warp and change, not for the better.11

Madison’s Presidency

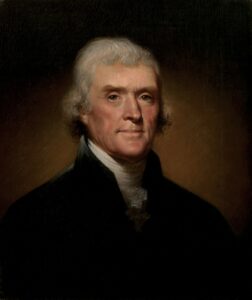

Madison’s friendship with Thomas Jefferson influenced his public political career after the founding of the U.S. Government, with Madison acting as the successor to Jefferson when he took office in 1809 and tying himself with the effects of Jefferson’s presidency, principally the stances that were taken between them and Europe during the war between France and England that was going on at the time, and the resulting embargo that Jefferson placed in order to keep America out of direct conflict. Early on, Madison was a fan of the initial French Revolution, supporting Jefferson in promoting the French cause. When the Reign of Terror began, the support from both men waned upon seeing the very tyranny of the majority that Madison made clear in the Federalist Papers and the Constitution, had no place in American governance. While he was in government, Madison opposed legislation he viewed as tyrannical and against the Constitution, including the creation of the National Bank, and negotiations with the British. This had caused friction within the Washington administration in years prior, and the resulting separation of Madison from Federalist support had catalyzed the creation of the Republican-Democrat party alongside Jefferson. While Madison was in office, he came under formidable scrutiny and opposition by everyone, including those in his own party who had not shared his more unique ideals. Confronted by both the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, Madison had been pressured to reverse his stance on numerous occasions, including having his and Jefferson’s embargo voted down and eventually getting Madison’s approval for instituting the Second National Bank. After the Louisiana Purchase was completed, neither the French nor the British were on good terms with the States, and continued their trade war as they fought, preventing the US from trading with either of them. In response, Madison reinstituted the embargo, to little of the desired effect, as both the French and the British were prepared for such a move in policy, but which had the ultimate result in making the US suffer.

In 1811, he reorganized his cabinet, bringing in James Monroe, whom he had won against in the 1809 election, to bring in a group of people who were better aligned with Madison’s ideas and policies, and could help make them a reality. This was also done to help insulate the executive from the changing stances of the Jeffersonian Republicans, who began to turn against Madison alongside the imploding Federalists, and had become increasingly hungry for war against the British. While Madison initially resisted the call for conflict, the British’s antagonistic actions towards the US, including inciting Native Americans on the frontier to attack and raid US cities, left Madison sending in a war request on June 1, 1812. Ironically enough, Madison and Jefferson oversaw the demilitarization of the US armed forces prior to this, ensuring that in order to wage war, Madison then had to recreate and bolster the newly reinstituted Army and Navy. While this was taking place, Madison’s belief in avoiding war, the very reason he installed the embargo in the first place, still held true, and he had quickly offered peace terms before the failed invasion of Canada. The British early in the war cared more about a strong Napoleonic France, as well as committing forces to Spain and Portugal, and so had not committed much of their forces to the American front. However, when France had to retreat from their invasion in Russia, the English began committing more forces to the American front, adding pressure to the freshly rebuilt US Navy and Army, who gradually rose to the challenge, fighting a war on multiple fronts against both the English in the north and the Native Americans in the west and south. By 1814, Madison had sent 5 diplomats to try and end the war peacefully as the army attempted to stall the British push into the states. However, when Chesapeake Bay was attacked by the British, he and his cabinet got personally involved. James Monroe himself had become a scout and Madison arrived in person to inspire the defenders, but this had not stopped the British from marching through Maryland to Washington D.C., where after the Bladensburg Races, the Capitol building and the White House were burned.

December of that same year, Madison resisted Federalist threats to secede from the union, their main demands revolving around a set of amendments that were written to limit the authority of the Jeffersonian Republicans, which on the surface, mirrored the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions that Madison and Jefferson wrote back in the 1790’s, creating an instance of Madison disagreeing with his own previous position. What makes this particularly odd but understandable is the motivations behind each instance. The Virginia Resolution that Madison wrote was in protest to the Alien and Sedition Acts in particular, while the Federalists ended up rejecting the idea of secession, their demands were based on exerting state control over the federal commerce and militia, based on the amendments that the New England Federalists during the Hartford Convention were putting forward. Andrew Jackson’s success in Louisiana’s Battle of New Orleans and the Treaty of Ghent ended the war in Madison’s favor, swinging public opinion further against the Federalists.12

His legacy was secured during his last years of presidency, after which he was able to permanently retire from politics following the end of his term, but his reputation as the last of the Founding Fathers followed him, and he was asked continually for guidance as the Union began showing signs of fracture. His stance after his presidency consisted of preserving the Union, an idea that was later mirrored by Abraham Lincoln 45 years later in the 1860’s. While he eventually was only able to barely stave off bankruptcy and was unwilling to sell his slaves in order to settle his debts, he did decide to back the American Colonization Society, a group dedicated to emigrating both freed and enslaved African Americans back to Africa. 13

Contemporary Perspectives (Beard, Gregory Weiner)

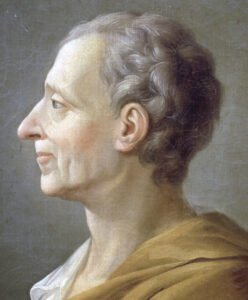

So, we looked at Madison from his actions, rationale, and policy, but there is one extra factor to consider, and that is to draw upon contemporary views that are used to characterize the man. Two prevailing views exist, that of Charles Beard, whose book in the 1910s had influenced not just the perception of the founding fathers, but the interpretation of the Constitution itself; and George Weiner, whose PhD dissertation acts as the opposing and more consistent view that lasts to this day.

To begin with, Charles Beard’s novel An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States, was released in 1913, during a time where “Theodore Roosevelt had raised fundamental questions under the head of ‘the New Nationalism’ and proposed to make the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies created by railways, the consolidation of industries, the closure of free land on the frontier, and the new position of labour in American economy.”

The central premise of the book was to look into the economic factors that played into the Constitution’s development and to attempt to discern the implications. Its relevance to James Madison comes in his interpretation of characters and situations the Founders were in during the time of the framing. Chapter 3 of his book goes into this detail, mentioning that the inability of the central government of the Articles of Confederation to generate any sort of revenue made situations worse economically as people began to rebel and investments were devalued. He alludes to the idea that changing the Articles had become an increasingly popular movement, which implies that there was more to the reasoning behind the secrecy of the Constitutional Convention that took place. For the part Madison played, Beard’s research noted that Madison had never been substantially rich, and so was more readily against the institution of the national bank, a position corroborated by his public policies at the time. He also discusses Federalist 10 later on, discussing and analyzing how economics have been a substantial factor in the presence of factions, and that while Federalist 10 applied to any and all differences of opinion, Beard wrote his book by looking solely from an economics lens, where the minority to be protected were the creditors, and “those who possess property to be attacked.” His conclusions about Madison’s philosophy was to be intertwined with his conclusions about Federalist 10, and his conclusions about the Constitution itself. He postulated that when the Constitution is seen through the economic lens, and thus can be considered an economic document, Madison may be seen as promoting the adoption of the Constitution so that the economic interests of specific peoples may be protected, particularly so those who have land and money need not fear rebellion and infringement on their ability to own and operate that land and income, and so that the Federalist and the Constitution by extension, had “every fundamental appeal in it is to some material and substantial interest.”14

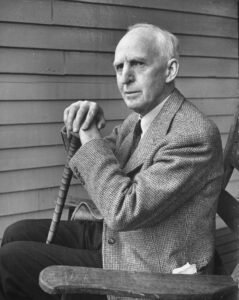

Dr. Gregory Weiner wrote a PhD thesis on Madison, titled Madison’s Metronome: The Constitution and the Tempo of American Politics, where he concludes that Madison’s structure and goal for the Constitution was to make a document that was designed to slow down majority rule, so that decisions could be made deliberately, describing this similar to music, “Madison assumed the natural pace of majoritarian politics was allegro; the Constitution’s purpose was to slow it to a steady but deliberate andante.” His research led him to believe that Madison had never believed in anything but majority rule, believing that while a majority is flawed and prone to mistakes, they hold the right to bind a community, and noticed that a majority will almost always get its way. His nuance then lay in which majority should be ruling. One key point that Dr. Weiner noted is that Madison had a lifelong concern about impulsive behavior in government, exemplified when “The majorities to which he objected were almost always those that formed, spread and prevailed quickly, a point underscored by his frequent portrayal of them with metaphors like fire and contagious epidemics that connoted sudden eruptions of sentiment sweeping across populations or political institutions before there was time for thoughtful consideration.” He uses Federalist 63 as evidence, where Madison’s governmental perspective is:

“As the cool and deliberate sense of the community ought, in all governments, and actually will, in all free governments, ultimately prevail over the views of its rulers: so there are particular moments in public affairs, when the people, stimulated by some irregular passion … may call for measures which they themselves will afterwards be the most ready to lament and condemn.”

When looking at this passage, Dr. Weiner connected this to various parts of Federalist 10, the Bill of Rights, and the Constitution utilized to slow down majority decisions, so that the majority that makes decisions are ones “seasoned by time.” He also spent the majority of his thesis analyzing various interpretations of Madison, systematically dismantling these perspectives to better understand Madison. He discusses views of Madison as someone protecting aristocratic interests, someone who was anti-majoritarian, and views that he was a majoritarian. Various priorities attributed, whether he was for or against liberty, were all mentioned and subject to scrutiny. What remained from Dr. Weiner’s analysis was that Madison was a majoritarian, but wanted to construct a government that took the majority’s decision-making process and slowed it down, allowing for decisions to be better understood and to be done in a manner that needed a longer consensus to be acted upon.15

Conclusion

With all the information that was gathered, the conclusion of Madison’s philosophy had been built up. Looking into his education, it became clear that he was incredibly invested in the concept of philosophy and law, which served him in his pursuit of an ideal form of government. From his prior experience with governments before the Revolutionary War, we pondered and learned about his core belief in religious toleration and his growing conceptualization of the necessity of liberty. From his own actions in government during and after the war, it is understood that Madison’s priority was liberty and to have the government be as opposite to tyranny as possible. We see how perspectives have changed over time, and how varying perspectives are reliant on different interpretations of the same information. Charles Beard proposed an aristocratic view of James Madison, while Greg Weiner countered by proposing the opposite: that Madison was a majoritarian. All of this is to figure out how Madison designed the Constitution to revive the fledgling United States. His solution, as we began to unravel and reveal, was to institute majority rule in a manner that, by design, was slow and deliberate, in order to protect the rights of everyone while making just enough compromises to keep the government working. He accomplished this through separating the government into various, smaller powers. He endeavored to keep these powers from influencing each other outside of providing a series of checks and balances, to provide no easy way for an abusive and impatient majority to prosper and enact changes that had the unfortunate yielding of destructive results.

- “James Madison,” accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.history.army.mil/books/RevWar/ss/madison.htm. ↵

- James Madison – 4th President of the United States Documentary, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyVi_clqe24. ↵

- “God In America: People: James Madison | PBS,” accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/godinamerica/people/james-madison.html. ↵

- James Madison – 4th President of the United States Documentary, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyVi_clqe24. ↵

- James Madison et al., “Convention and Ratification – Creating the United States | Exhibitions – Library of Congress,” webpage, April 12, 2008, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/creating-the-united-states/convention-and-ratification.html. ↵

- “Federalist Papers: Summary, Authors & Impact,” HISTORY, June 22, 2023, https://www.history.com/topics/early-us/federalist-papers. ↵

- “U.S. Senate: The Virginia Plan,” accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.senate.gov/civics/common/generic/Virginia_Plan_item.htm. ↵

- James Madison et al., “Convention and Ratification – Creating the United States | Exhibitions – Library of Congress,” webpage, April 12, 2008, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/creating-the-united-states/convention-and-ratification.html. ↵

- James Madison – 4th President of the United States Documentary, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyVi_clqe24. ↵

- Ken Drexler, “Research Guides: Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History: Federalist Nos. 1-10,” research guide, accessed January 22, 2024, https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-1-10. ↵

- Ken Drexler, “Research Guides: Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History: Federalist Nos. 51-60,” research guide, accessed January 22, 2024, https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-51-60. ↵

- “The Proceedings of a Convention of Delegates . . . at Hartford, in the State of Connecticut, December 15, 1814, by the Hartford Convention, 1815 | U.S. Capitol – Visitor Center,” accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/artifact/proceedings-convention-delegates-hartford-state-connecticut-december-15-1814-hartford. ↵

- James Madison – 4th President of the United States Documentary, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyVi_clqe24. ↵

- “An Economic Interpretation of The Constitution of The United States,” Charles A. Beard, accessed January 22, 2024, https://people.tamu.edu/~b-wood/GovtEcon/Beard.pdf ↵

- “Madison’s Metronome: The Constitution and the Tempo of American Politics,” Gregory S. Weiner, accessed January 22, 2024, https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/558058/Weiner_georgetown_0076D_10728.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y ↵