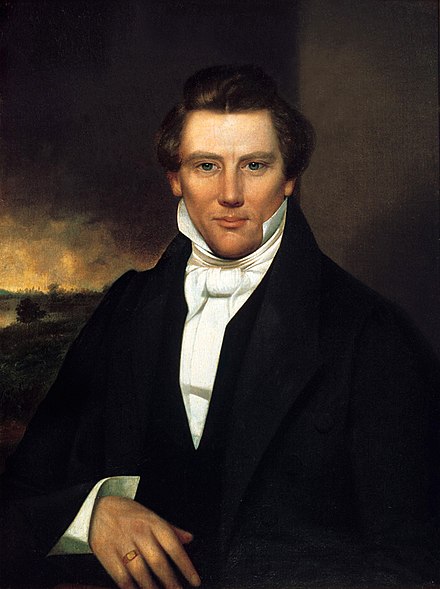

In the nineteenth-century United States, the Second Great Awakening saw the rise of many new religious movements. One of these movements was the Latter-day Saint movement, started by Joseph Smith, who founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, more commonly known as the Mormon Church. After years of political turmoil and antagonism towards Joseph Smith and Mormonism, Smith and his followers settled in the town of Commerce, Illinois, which the Latter-day Saints later renamed Nauvoo. Smith became Mayor of Nauvoo, and was able to achieve relative peace within his community, despite disagreements about some of the new doctrines of the Latter-day Saint Movement, and despite the prominence of anti-Mormonism in neighboring communities within Hancock County, who feared Smith wanted a theocracy, and feared that Mormons could become a political majority in the county.1 Smith, however, looked beyond Hancock County and Illinois, and sought to secure political protection for Mormons. He reached out to the major presidential contenders for the 1844 presidential election, including Henry Clay, Martin Van Buren, and John C. Calhoun.2 The contenders received Smith’s letters, but none made any assurances to protect him or the Latter-day Saints Movement, and some didn’t respond at all. Smith desired to make a bold statement and widely publicize his desires for the Latter-day Saints movement, and in January of 1844, he announced his candidacy for the Presidency of the United States.3

Joseph Smith ran as an Independent candidate, supporting the gradual abolition of slavery, reestablishment of a national bank, territorial expansion, vigorous protection of religious liberty, and radical prison reform.4 Many within the Mormon community were enthusiastic about Smith’s campaign for president. Brigham Young, the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and future Latter-day Saints leader, traveled east to campaign for Smith. However, this enthusiasm for Smith’s campaign did not end ongoing problems and division within the church.

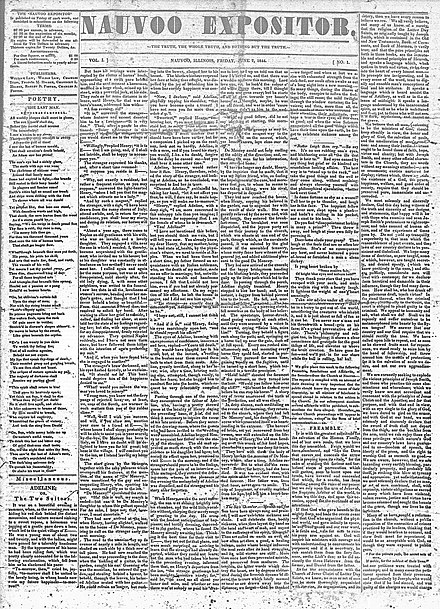

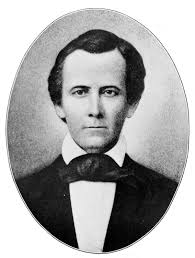

The divisions in the Mormon church primarily stemmed from Smith’s new doctrine that allowed plural marriage, in which a man could take more than one wife. This doctrine of polygamy faced opposition from many members of the church, particularly those who were early embracers of Mormonism, when it was more similar to Christianity.5 One dissenter to this new doctrine was William Law, a counselor of Joseph Smith as a member of the church presidency. Due to his opposition to polygamy, William Law was excommunicated from the Mormon Church in April of 1844, along with several other dissenters.6 Law then founded a splinter group known as the True Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. William Law and other dissenters then decided to publish a newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor, to oppose Smith and his new doctrines. In its first and only publication on June 7, 1844, the newspaper sought to “explode the vicious principles of Joseph Smith, and those who practice the same abominations” and decried the excommunication of the dissenters, the practice of polygamy, and other practices they saw as corrupt.7 The Expositor also commented on Smith’s presidential campaign, facetiously remarking that Smith wasn’t suitable for the presidency due to his “candidacy” for the state government at Alton, where Illinois’s state penitentiary was located.8

The publication of the Nauvoo Expositor outraged Joseph Smith. He and the Nauvoo City Council declared that the paper was a nuisance and ordered the Expositor’s printing press and issues to be destroyed. The Nauvoo Legion, a militia that was loyal to Smith, carried out Smith’s order and destroyed the printing press, burning it along with all issues of the Nauvoo Expositor.9

After the destruction of the Expositor’s printing press, William Law traveled to nearby Carthage, Illinois and filed charges against Joseph Smith, accusing him of inciting a riot. The Sheriff in Carthage, David Bettisworth, went to Nauvoo to arrest Smith, but returned to Carthage empty-handed. The Sheriff said that Smith had refused to go and would only be tried in Nauvoo. Smith was detained in Nauvoo, but sued for a writ of habeas corpus in the municipal court, was granted such, and was then freed.10 After being freed, Smith declared martial law in Nauvoo and called the Nauvoo Legion together to prepare for the possibility of violence against him and the town.11

Smith’s destruction of the printing press caused a far greater uproar than the contents of the Nauvoo Expositor did. This outrage was not only among his dissenters, but among nearby towns with preexisting anti-Mormon sentiment. Ardent anti-Mormon Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal in Warsaw, Illinois, called for war against Smith, calling Nauvoo “the enemy camp.”12 Additional rumors of the scope of the Nauvoo Legion’s numbers and armament further stoked fear in Nauvoo’s neighboring communities, and Smith’s refusal to be tried outside Nauvoo only intensified the outrage. Calls were made for the Governor of Illinois, Thomas Ford, to authorize the state militia to arrest Smith, and armed volunteers gathered in Carthage preparing for the possibility of violence. Governor Ford sent a letter to calm the men in Carthage, and later traveled to Carthage to address Smith’s actions and decide what action would be taken. Ford wrote a letter to Joseph Smith, saying that Smith would be arrested but promised him a guarantee of safety. Ford then tasked a posse to arrest Smith; however, when the posse arrived in Nauvoo, Smith was nowhere to be found.13

Smith learned of the men in Carthage that gathered to arrest him, and despite Governor Ford’s letter promising him safety, decided to flee for his own safety. Smith, along with his brother Hyrum and a few of his followers, left Nauvoo, crossing the Mississippi river into Iowa. Smith planned to flee to the Rocky Mountains and for his wife and children to be transported to Cincinnati. A messenger from Nauvoo told Smith that his wife refused to leave and pleaded for Smith to return. Smith’s other followers also pleaded for him to return, some accusing him of cowardice, and some saying they were concerned for Nauvoo’s safety, that the city might be attacked if Smith did not surrender. After his brother encouraged him to return to Nauvoo, Smith obliged. Once arriving back in Nauvoo, Smith messaged Governor Ford to tell him he intended to surrender himself to Carthage.14

Joseph Smith and his brother departed for Carthage on June 24. On their way, they were intercepted by Captain Dunn, who led the McDonough County militia, taken to Carthage, and placed in the Carthage jail. Smith was then charged with treason for declaring martial law in Nauvoo.15 Smith requested a meeting with Governor Ford, who granted him one on June 26. Smith was concerned for his safety, worrying that the militiamen that gathered in Carthage might attempt to take the law into their own hands, but Governor Ford dismissed his concerns.16 Smith was granted visitors, and one of them gave Smith a pistol in order to defend himself if he had to.17

Governor Ford sought to absolve the possibility of action by the Nauvoo Legion, and requested they surrender their weapons. Smith concurred in a desire to maintain law and order, and ordered the legion to surrender their weapons to the Governor. Governor Ford then ordered most of the militiamen that had come to Carthage to disband and return to their homes, save three companies of troops. Two companies would guard the Carthage jail, and one would accompany him to Nauvoo so he could address Smith’s arrest to his followers. Ford departed on the morning of June 27, and left the anti-Mormon Carthage Boys to guard the Smith brothers in the Carthage jail. Ford was informed of the possibility of an attack on Joseph and Hyrum Smith, but dismissed the notion, citing the integrity of the captain of the Carthage Boys, R.F. Smith. Ford had faith that Captain Smith wouldn’t disobey his order to protect the jail with his life.18

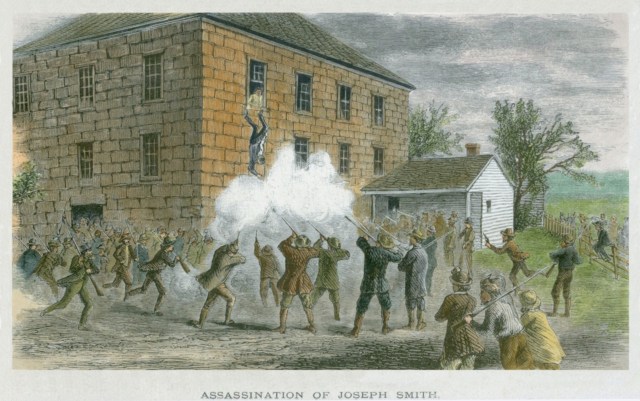

Later the same day, the anti-Mormon militia began their plans to exact their own kind of justice. The militias from nearby towns Green Plains and Warsaw were informed by Thomas C. Sharp that Ford left Carthage for Nauvoo, and the militias saw their opportunity and marched into Carthage. Many members of this mob blackened their faces with gunpowder and dirt. The mob appeared to have been met with some resistance from the Carthage Boys, who fired their guns at the mob, though the Carthage Boys had anticipated the attack and loaded their guns with blanks. The mob breached the jail and went upstairs to the room where Joseph and Hyrum Smith were being held. When the mob arrived, the Smith brothers were being visited by Mormon disciples Willard Richards and John Taylor, the former looking out the window and seeing the incoming mob.19

Hyrum Smith attempted to bar the lockless door, but was taken aback by a shot the assailants fired through the door. The assailants breached the door, shooting Hyrum Smith in the face, killing him. Joseph Smith grabbed his pistol and fired six times at the assailants, three purportedly wounding three of them. John Taylor tried to escape out the window, but was wounded by a shot to the leg and was further wounded by three more shots as he tried to crawl to safety. Smith then tried to escape out the open second-story window, but was struck twice in the back by the assailants and again in the chest by an assailant on the ground. Smith fell out of the window onto the ground below, dead. Some reported that after falling, Smith was propped up against the well outside and shot four more times, though this is only conjecture. Having completed their goal, the mob then dispersed, leaving Joseph and Hyrum Smith dead, John Taylor wounded, and Willard Richards with only a few nicks and bruises.20

Thomas C. Sharp and seven other anti-Mormons were arrested for the murder of the Smith brothers, though all were acquitted at trial later that year.21 Smith’s candidacy and murder had no impact on the 1844 presidential election, in which Democratic candidate James K. Polk defeated Whig Party candidate Henry Clay. In the years after Smith’s death there was a schism among Latter-day Saints, and Brigham Young would lead an exodus of most of the Latter-day Saints from Nauvoo and eventually settle in Utah, where they would find safety and be able to flourish.22

- Marvin S. Hill, “Carthage Conspiracy Reconsidered: A Second Look at the Murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 97, no. 2 (2004): 109-110. ↵

- Timothy L. Wood, “The Prophet and the Presidency: Mormonism and Politics in Joseph Smith’s 1844 Presidential Campaign,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 93, no. 2 (2000): 179-80. ↵

- Timothy L. Wood, “The Prophet and the Presidency: Mormonism and Politics in Joseph Smith’s 1844 Presidential Campaign,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 93, no. 2 (2000): 178-80. ↵

- Timothy L. Wood, “The Prophet and the Presidency: Mormonism and Politics in Joseph Smith’s 1844 Presidential Campaign,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 93, no. 2 (2000): 180. ↵

- Timothy L. Wood, “The Prophet and the Presidency: Mormonism and Politics in Joseph Smith’s 1844 Presidential Campaign,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 93, no. 2 (2000): 188. ↵

- Marvin S. Hill, “Carthage Conspiracy Reconsidered: A Second Look at the Murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 97, no. 2 (2004): 116. ↵

- John E. Hallwas and Roger D. Launius, “The Nauvoo Expositor,” in Cultures In Conflict: A Documentary History of the Mormon War in Illinois, (University Press of Colorado, 1995) 142-48. ↵

- Timothy L. Wood, “The Prophet and the Presidency: Mormonism and Politics in Joseph Smith’s 1844 Presidential Campaign,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 93, no. 2 (2000): 189. ↵

- Marvin S. Hill, “Carthage Conspiracy Reconsidered: A Second Look at the Murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 97, no. 2 (2004): 116. ↵

- George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 392. ↵

- Marvin S. Hill, “Carthage Conspiracy Reconsidered: A Second Look at the Murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 97, no. 2 (2004): 117. ↵

- Marvin S. Hill, “Carthage Conspiracy Reconsidered: A Second Look at the Murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 97, no. 2 (2004): 117. ↵

- George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 392-95. ↵

- George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 395-96. ↵

- George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 396. ↵

- George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 402-03. ↵

- Marvin S. Hill, “Carthage Conspiracy Reconsidered: A Second Look at the Murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 97, no. 2 (2004): 118. ↵

- George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 397-401. ↵

- George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 405-06. ↵

- George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 406-07. ↵

- Marvin S. Hill, “Carthage Conspiracy Reconsidered: A Second Look at the Murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 97, no. 2 (2004): 118; George R. Gayler, “Governor Ford and the Death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1908-1984, 50, no. 4 (1957): 409. ↵

- Timothy L. Wood, “The Prophet and the Presidency: Mormonism and Politics in Joseph Smith’s 1844 Presidential Campaign,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 93, no. 2 (2000): 190. ↵

5 comments

Jordan Robbins

Hi, through your writing I learned so much about Sr. Joseph. Its so crazy to know that this was so long ago that happened and that his story could be forgotten but, I’m glad you made this to remind us of his great leadership and story. Even though it was sad he was a staple for freedom! Thank you for making this!

What made you interested in his story?

Macarena Machado Combe

Joseph Smith’s resilience and strategic thinking were clear throughout the article. This was evident when he reached out to major presidential contenders in the 1844 election, hoping to secure political protection for the Mormons. Ultimately, his decision to surrender himself to Carthage, despite the personal risk, showed his commitment to his people and his complex character as a leader. This article demonstrates the difficulties that being a leader may bring and how a leader always has to act in benefit to his community with a selfless mindset. Finally, the article was well written, informative and specific.

Zoe Klupenger

Hi Parks! This infographic does a great job emphasizing Joseph Smith’s leadership and life. I like how you have everything organized, and the visuals you picked along with it. I personally have not heard of his story, so I definitely think you did a good job explaining everything. Good job! Were there any facts you learned that you did not add in?

Danielle Villanueva

This article provides a fascinating look at Joseph Smith’s complex life and tragic end. I learned about the religious tensions and conflicts surrounding the early Mormon movement. The detailed account of Smith’s presidential campaign and his murder in Carthage jail was particularly gripping. I would have appreciated more context about the broader social climate of 1840s America that led to such intense religious persecution.

Alysia Cano

Joseph Smith’s life and leadership were marked by extraordinary vision and resilience in the face of intense opposition and hardship. His presidential campaign, though ultimately cut short, reflected bold ideals and a desire to advocate for religious freedom and social reform. The tragic events at Carthage Jail serve as a poignant reminder of the tensions of the era and the sacrifices made in the pursuit of faith and community.