The years of 1026 to 1031 CE saw the Kingdom of Norway gripped in a war over land and power. At stake were its sovereignty, vied for by two historically ambitious men. The first was Olaf Haraldsson, or King Olaf II, of Norway. The second, was Cnut the Dane, or King Cnut, of England and Denmark. While King Olaf II played a critical role in the conflict between both nations, to understand the inception of the conflict itself, we must first understand the motivations of the latter.1

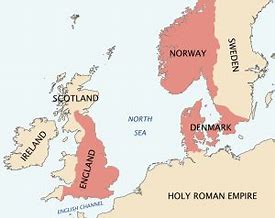

King Cnut had seized the throne of England in the year 1016 during the Viking invasions and occupations that had been taking place there since the tenth century. Upon taking the throne, he firmly established himself as a culturally Anglo-Saxon ruler and strove to rule as such. Two years later, he inherited the Kingdom of Denmark upon his brother Harold’s death in 1018.2 Cnut’s actions at consolidating his now extensive holdings are seen in his utilization of the Catholic church’s authority for administrative and socio-religious purposes in his new empire.3 A unique factor attributed to Cnut himself would be his religious affiliation to Christianity. His father, Sweyn, had been baptized into the Christian faith, and Cnut considered himself Christian by the time of his ascension to the English crown. Yet, Cnut’s army during the invasion of England was likely largely pagan in their beliefs, and even during his reign, pagan worship continued in certain parts of England and Denmark, even as Christian missionaries continued to grow their influence in both regions. This mixing of faiths would generate a modest degree of tolerance from Cnut towards those of other pagan faiths, and this sentiment would have a large influence over Cnut’s decision to wage war against Norway.4

Originally the son of a Norwegian petty king, Olaf Haraldsson had spent his teenage and early adult years as a Viking and mercenary. In a similar fashion to Cnut, he too was baptized (sometime in the year 1015 in Normandy) and would also find success in unifying a nation under his rule, deposing the ruling Hakonarson family from Norway in 1016.5 Upon seizing the throne, he would dub himself Olaf II, after the late king Olaf I, and would soon seek to assert his dominance over his new dominion.6 Olaf’s bold move of unification would soon put him in Cnut’s sights for two reasons. The first reason was that the Hakonarson family were vassals of Denmark since Cnut’s father, Sweyn Forkbeard, and his allies in Sweden had conquered the region, divided it among themselves, and put those friendly to their rule in control. Since Cnut had inherited the Danish throne, he likewise inherited the authority over his Norse vassals. Olaf’s actions in turn proved to be a direct challenge to Cnut’s authority.7

The second reason was his alienation from the Norwegian aristocracy and his zealous enforcement of Christianity.8 His destruction of pagan temples, the expulsion of pagans from their homes, executions of pagans, and the lesser punishments of binding and maiming all displayed the religious intolerance that marked Olaf’s reign.9 This would lead to a large exodus of both aristocrats and pagan commoners to the shores of England and Denmark, with the aristocrats and prominent landholders from Norway expressing their support for Cnut’s authority over Olaf’s for the Norwegian throne. Perceptive to what holding the Norwegian throne would mean, Cnut began to plan his intervention.10

Here, we see the expansionist ambitions of Cnut surface in a series of acts between the years 1022 and 1027, the first act being the subjugation of the Slavic tribes east of Denmark in order to secure his southern border. The second act was his alliance with the German king Conrad II in order to secure the Baltic border controlled by the Holy Roman Empire at the time.11 The third act was his Letter to the English, written in 1027, a declarative address that set forth Cnut’s claim as king of all England, Denmark, Norway, and certain parts of Sweden, and sought to cast Cnut as emperor on a larger continental stage. While this address would come after he began his departure to Norway, it firmly addressed his ambition for a larger domain overseas.12 The fourth, and most decisive act Cnut undertook to solidify his conflict with Norway, was his dispatch of a delegation to Norway in 1025, who brazenly presented his claim of authority over the Norwegian throne, citing that his ancestors had exercised authority in that region and that if he wanted, Olaf could continue to rule as his tributary vassal. Olaf, in response, would do the exact opposite of submitting. He rejected Cnut’s offer of submission and swore to defend Norway until his dying day. With war on the horizon, he quickly sought an alliance with Anund Jacob, his brother-in-law and King of Sweden. With Norway unwilling to concede, both Olaf and Cnut began preparing their forces for war.13

The first major battle of the war would occur in September of 1026 at the Kattegat, the body of sea that separates the Danish peninsula and the Straits of Denmark from the southern shores of Sweden. Cnut, having combined his English fleet with a Danish fleet commanded by Earl Ulf of Denmark, quickly took advantage of the combined strength of his fleets and cut off Olaf’s access out of the Kattegat. Seeing his path blocked, Olaf retreated eastward to combine his force of about sixty ships with those of the Swedish fleet, led by Anund Jacob. With a combined force of about 420 ships, the Norwegian-Swedish fleet was still outnumbered by the English-Danish fleet of about 630 ships, prompting Olaf and Anund Jacob to devise a way to even the numerical odds. This was done by Olaf giving Anund Jacob control over the entire fleet and having it land east of the River Helgea (translated as “Holy River”), an outlet for several smaller, interconnected lakes further inland. Olaf then led a force of men inland and began to dam up the entrance of the outlet, thereby raising the water levels of the nearest tributary, Lake Hammersjon, and felled large trees from the surrounding areas which were laid next to the riverbed. As this was being done, Olaf had ordered the ships of the fleet to be lashed together, effectively forming a floating blockade east of the river.14

Soon enough, Cnut’s scouts had spotted the Norwegian-Swedish fleet, and their findings prompted Cnut to bring the full force of his fleet into view. Having been alerted to the English-Danish fleet’s presence, Olaf ordered his ships to sea. Seeing that the enemy fleet had the defensive advantage, Cnut declined to engage the enemy fleet and instead ordered his men to shelter towards the mouth of the river. As Cnut’s men began to make landfall and set up their camps, Olaf saw the chance to spring his trap. As dawn of the next day approached, Olaf’s men pushed the large, felled trees into the Lake Hammersjon tributary and then broke the dam to the opening of the outlet. The rushing water forced its way out of the tributary, through the outlet, and right into Cnut’s men and ships. The tree trunks pushed into the water were rammed into Cnut’s ships by the force of the rushing water, and the water itself destroyed the surrounding riverbanks and drowned the men encamped on them. The ships that were fortunate to escape the geographic onslaught were sent adrift in the bay, as the mooring that held them down were knocked loose by the force of the water. Witnessing the disarray that engulfed the English-Danish fleet, Olaf and Anund Jacob took their fleet and planned to sail along the coast of Bleking. Cnut, seeing that his fleet was in no condition to pursue, sent scouts inland to pursue the path of Olaf’s fleet and blockaded the straits leading in and out of the Kattegat should Olaf attempt to travel back to Norway.15

Following this battle, there are three key developments that took place between the Fall of 1026 and the Spring of 1028. The first was Cnut’s pilgrimage to Rome in early 1027 and his desire to secure his northern English border with the kings of Scotland. His reason for doing so was based on the fact that the winter months of 1026 were not ideal for mounting an offensive against Norway, and he found more value in completing the former goals before resuming hostilities. The second development was the abandonment of Olaf by his chieftains following the battle at Helgea. As mentioned previously, Olaf and Anund Jacob had planned to sail along the coast of Bleking in order to regroup after the battle; however, many of the men under their control had opted instead to sail back to their homes in defiance of their leaders’ plans. This left Olaf and Anund Jacob with close to 160 ships, too few to afford another confrontation with Cnut, causing them to rethink their plans. Ultimately, both men could not come to an agreement on what to do next, with Anund Jacob settling to spend the winter in Sweden and prepare an offensive the following Spring, while Olaf began to march his army overland back to Norway. The third, and possibly most effective development in shifting the tide of the war, was the successful infiltration of Cnut’s agents into Norway. The agents would attempt to sway Norwegian lords and landholders to Cnut’s side, and by 1027 had experienced strong success in their efforts at convincing their targets to join their cause. A notable figure who changed allegiances at this time was the powerful Norwegian Lord Erling Skjalgsson, who gave the agents protection during the war.16 This pause in direct offensives and increase in subversive activities would show its effects when Cnut would make his next move in the Spring of 1028.

In a similar fashion to 1026, Cnut would sail forth from England and once again combine with his Danish forces, only this time their numbers were greater, with estimates of around 900-1200 ships under his command. In contrast, the defection of Norwegian nobility and unpopularity among the general populace hindered Olaf’s efforts at recruitment, and he had only managed to garner a small levy. After sending for his ships in Sweden, Olaf sheltered at his court in Tunsberg, along the Oslo Fjord on the west bank. Cnut at this time would bypass the Oslo Fjord and began to consolidate his support within Norway by hosting a series of Things, or the Germanic equivalent of a governing assembly, as he sailed up its rivers. These meetings would be between Cnut and the Norwegian freemen of the regions he passed through, where the freemen would accept Cnut as their king, and Cnut in turn would appoint local officials. The most important Thing would occur at Nidaros, the Norwegian capital, where Cnut would ultimately be appointed king of Norway by the eight districts of the central Norwegian region. This appointment would give Cnut dominion over all of Norway and its overseas territories in the Shetlands, Orkneys, along the Scottish coasts, and in Greenland. Cnut would first appoint his nephew Earl Hakon as Viceroy over Norway, but on a trip back to Norway from England in late Autumn of 1029, he disappeared at sea and was never seen again. He was then replaced by Cnut’s illegitimate son Sweyn, whom Cnut would grant the title King of Norway. It is important to note that Cnut’s assumption of the Norwegian throne from 1028-1029 had been relatively peaceful, with no major offensives taking place between his forces and the Norwegians.17

While Cnut was occupied with managing affairs of state and administering leadership positions among his nobility, Olaf was busy consolidating what forces he could muster and found success along Norway’s western coast, where civilians loyal to him guided his forces to safety. News of Earl Hakon’s disappearance had reached Olaf just before Christmas in 1029, at which point he had already been exiled in Russia for a year. Sensing an opportunity to improve his position, Olaf set sail from Russia to Sweden, where he was greeted by his loyalist allies and received 400 men from Anund Jacob’s elite guard to add to the 200 men Olaf had when he went into exile. Along his way to Norway, he gathered to his banner the remainder of the loyalist chiefs with their men, as well as criminals and other outcast who were promised rewards for their service. Yet despite Olaf’s need for manpower, he turned away about 500 men who refused to be baptized, costing him valuable help in his efforts to reconquer his homeland. Hearing of Olaf’s gathering forces, the lords of Norway prepared to face him directly on land. Olaf would ultimately march his forces towards the capital of Nidaros and meet the defending force, led by Kalf Arnason, at the Stiklastad farmstead, about forty miles northeast of the capital.18

Olaf fielded about 3,000 men, while Kalf had around 10,000. Olaf had a rather valuable advantage, as his men were hardened veteran warriors, while Kalf’s men were predominantly farmers and unskilled laborers with limited martial abilities. At noon on the day of the attack, Kalf, aided by Lord Harek and Thor “the Dog,” began his march on the battle lines of Olaf, who had positioned his force in and around the farmstead. The first to engage were Thor the Dog and his vanguard, who marched forward flanked by their Norwegian levies. Olaf in turn ordered his men to charge downslope, which resulted in a successful routing of the levies, leaving Kalf exposed to Olaf’s men. Kalf and his housecarls would stand their ground and face Olaf’s men, giving some of the Norwegian levies time to regroup and mount a counterattack into the flanks of Olaf’s men. The fighting was wrought with stiff and fierce fighting on both sides as the casualties began to rise. Olaf began to lose members of his elite guard during the fighting, and he eventually faced off directly against Kalf, Thor the Dog, and their housecarls. While Olaf turned to face Kalf and his retinue, his marshal Bjorn faced Thor the Dog. Bjorn turned his axe and overhand struck Thor on his shoulder. Thor stumbled backward but countered with his spear, which he ran through Bjorn killing him. Olaf, in a similar fashion, would suffer an axe strike above his left knee, stumble towards a rock, and suffer a spear strike from Thor, who had turned his attention towards Olaf. The strike cut under Olaf’s mail armor and struck him in his stomach. The killing blow, however, came from Kalf himself, who struck Olaf on his neck, killing him. The last of Olaf’s guard, surrounding his body and standard, would fight until every last one had been killed. The remainder of Olaf’s force, now being led by Dag Hringson, soon found themselves overwhelmed and quickly retreated with the last of Olaf’s men. The Battle of Stiklastad lasted about two hours, and with Olaf’s death, the immediate threat to Cnut’s authority over Norway was defeated.19 However, the political unity now experienced by England, Denmark, and Norway was to be short lived.

The years following the war under the reign of Sweyn saw the once loyal Norwegian nobility, among them Kalf, begin to abrade under Sweyn’s authority, and soon they began to endow their support onto Olaf’s illegitimate son Magnus.20 In an ironic turn of events, in the year following Olaf’s death, the Norse church, which had received Olaf’s full support at this point in his reign, decided to canonize Olaf as a saint, and his death was seen as a martyrdom. This would completely undermine Cnut’s authority in the region, as support for the now Saint Olaf II of Norway translated into support for his son Magnus.21 The death knell for Cnut’s authority in Norway came from, incidentally, his own death in 1035. Once his son Sweyn had lost the support of the Norwegian nobility, and now his father, he would abdicate the Norwegian throne that same year without conflict, and would be replaced with Magnus as king.22 Magnus the Good, son of the holy king, would take the throne and officially end the Anglo-Saxon/Danish rule over Norway.

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 13. ↵

- Laurence M. Larson, “The Political Policies of Cnut as King of England,” The American Historical Review 15, no. 4 (1910): 733, https://doi.org/10.2307/1836956. ↵

- Laurence M. Larson, “The Political Policies of Cnut as King of England,” The American Historical Review 15, no. 4 (1910): 733-734, https://doi.org/10.2307/1836956. ↵

- Laurence M. Larson, “The Political Policies of Cnut as King of England,” The American Historical Review 15, no. 4 (1910): 737, https://doi.org/10.2307/1836956. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 13. ↵

- Lesley Abrams, “The Anglo-Saxons and the Christianization of Scandinavia,” Anglo-Saxon England 24 (1995): 223. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 13. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 13. ↵

- Lesley Abrams, “The Anglo-Saxons and the Christianization of Scandinavia,” Anglo-Saxon England 24 (1995): 223. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 13. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 13. ↵

- Catherine E. Karkov, “Conquest and Material Culture,” in Conquests in Eleventh-Century England: 1016, 1066, ed. Laura Ashe and Emily Joan Ward, NED-New edition (Boydell & Brewer, 2020), 188, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvrdf1qb.15. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 14. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 14. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 14. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 15. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 15-16. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 16. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 16-18. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 18. ↵

- Laurence M. Larson, “The Political Policies of Cnut as King of England,” The American Historical Review 15, no. 4 (1910): 742, https://doi.org/10.2307/1836956. ↵

- Sidney E. Dean, “Embracing the North Sea: Cnut’s Conquest of Norway,” Medieval Warfare 2, no. 1 (2012): 18. ↵