April 6, 2024

La Malinche: Mother of All Mestizos

La Malinche is a woman with many names and with a complex story. Malinal was her name given at birth, after “Malinalli” following the customary tradition of being named after the day of birth. Being born as the daughter of a chief granted her education and privilege in the Aztec civilization. This privilege was turned into a life full of turmoil and displacement following her father’s death and her mother’s remarriage. Malinal was sold to Mayan slave traders by her own mother who covered it by holding a mock funeral for Malinal due to the fact that selling children was unacceptable in Aztec culture. After becoming valuable due to her knowledge of both native languages, she was given to Hernán Cortés as a gift along with nineteen other maidens. With this, she gained her Spanish name, Marina, and due to her education and distinguishment, she was able to gain the respect of the conquistadores who referred to her as Malintzin, using “tzin” which was the standard honorific title.1

With her ability to translate, Cortés took an interest in Doña Marina, and she was his guide through his conquering of the Americas. The Spanish called her “La Lengua” or the interpreter. She was one of many indigenous women who were sought by Spanish men to establish romantic relationships to assert power dynamics, but her relationship with Cortes was more of a partnership. While she allowed him to conquer the Americas, she was promised “more than liberty” by Cortes.2 With this promise, she became the mistress of Cortés and an intelligent diplomat in the conquering of Mexico. As a sign of respect, she was granted the title Doña, which was a term granted to women of rank. While many claim that Marina was an ambitious, selfish, traitor for becoming the mistress of a Spanish conquistador, it is often forgotten that she was given to him as a slave. She had no real choice, as her life was dedicated to obeying and submitting to her owner. Through the journey of being his guide, translator, and interpreter, she chose to suffer the abuse from Cortés to remain alive and respected. The writings of her life even portray the partnership as a love story that led to the creation of a new, mixed race, but it is not known whether their firstborn was something that she wanted or a forced pregnancy by Cortés. Her influence on Cortes was so great for him, that he took her by his side on further conquests, and with this they had their first child, the first Meztiso, Martin Cortés.3

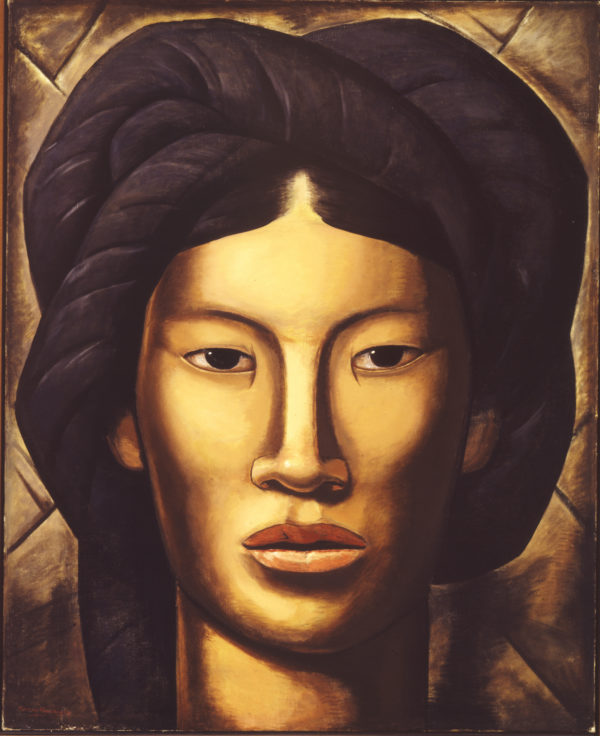

Collection of La Salle University Art Museum

Her biggest influence on Mexico’s history is the meeting between Moctezuma and Cortés, a meeting in which Doña Marina was the interpreter. While Cortés is credited for taking down the Aztec empire for killing Moctezuma, La Malinche was the woman who made it happen by having the trust of the indigenous and using it to avoid an attack plotted against the Spaniards.4 The action of telling Cortés about the attack that the Aztecs had planned against him was the act that had La Malinche labeled as a traitor to her native people. This problematic act was so important that it still lingers in today’s Mexican society in the term Malinchista(o), which refers to someone who prefers and shows interest in a foreign country and rejects their own culture.5 There is a huge sense of irony in how this term is used and La Malinche’s story and that is the way in which she navigated a complex ongoing conflict in which it was her life in danger is being misconstructed into her having admiration for the Spanish men and hatred for her people is disappointing. Her betrayal of the native people and support of the Spanish colonizers portrays Malinche as “the ethnic traitress supreme” in Mexican history, but this leaves out the possible reasons that led to her betrayal.6 If we look at her personal life, she was betrayed by her own family in the Aztec civilization who cast her out into slavery to grant success for her step-brother and who made her live as a woman forced to use her intelligence to further the cause of the Spanish against her native community. Even after examining her relationship with Cortés, you can see that there was not much equal power between the two, she was still his slave regardless of the honorifics they granted her and the freedom they promised her.

Wikimedia Commons

With this complicated and rich background, it is almost impossible to have different accounts of her life from various people. Although Malinal herself never left a record of her own story, men from her time took the time to write about her incredible influence on Mexico’s history and how she lived her life after Cortés. After boarding on the conquering journey with Cortés, la Malinche married a Spanish hidalgo named Juan Jaramillo and had a daughter whose name was Maria.7 It is said that Malinal did not live more than a decade after her marriage, and that is probably the reason for the lack of records about her. Because she was married and had children with Spaniards, she and her children were part of Spanish nobility, and with this came an additional name for her: The mother of all Mestizos. Now many consider the sole act of her having children with Spanish men the bigger betrayal to her native roots, but those same many fail to realize that for the majority of her life, she was the one suffering betrayal and manipulation. She was only a young Aztec girl who got betrayed by her mother, got cheated by the Mayans, and then got abused and deceived by the Spanish. For this she is called a traitor? When all her life it was all she knew?

Many make the connection with her and the term “La Chingada” for being a woman who in a way accepted her sexual abuse at the hands of Cortés and betrayed herself. I find it an interesting concept because this would make Mestizos the children of the abused, or in the famous saying, “los hijos de la chingada.”8 In Mexican culture, there is an important female figure that represents the role model for women, a woman who is a clean, caring, and pure more: La Virgen de Guadalupe. La Malinche is seen as the opposite of this figure. She is seen as a filthy, traitorous, selfish woman and mother. La Malinche is depicted as the adulterated woman who allowed for hybridity between two opposing identities and was cursed rejecting her resilience, and those who do it do not comprehend the complexity of her history. When Mexicans use and shout the saying “hijos de la chingada” it is in a negative way, usually filled with hatred and a sense of superiority. If we connect this to La Malinche and Hernan Cortés, it is obvious that many reject and abhor coming from either background.9 It is disappointing to see that people in Mexico have still not forgiven her despite knowing the suffering she had, yet she forgave the main person that hurt her: her mother.10

La Malinche’s legacy as the mother of all mestizos is a complicated and contested narrative that conveys colonialism in the Americas in a way that connects to various groups of people. While her role as an intermediary between indigenous groups and Spanish conquistadors has been villainized by some and used as a way to reject one’s native roots, her influence transcends mere historical documentation and that is truly undeniable. She is the symbol of the union of cultures, the blending of opposing identities, and the creation of a new identity that defines a huge part of current Latin America.11 By acknowledging her as the mother of all mestizos, we recognize the rich and colorful culture that is built in Latin America in a way that recognizes the resilience and incontestable spirit of those like la Malinche.

- Cordelia Candelaria, “La Malinche, Feminist Prototype,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 5, no. 2 (1980): 1–6, https://doi.org/10.2307/3346027. ↵

- Angelica Aboulhosn, “La Malinche, Hernán Cortés’s Translator and So Much More,” Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities 44 No. 1 (2023): https://www.neh.gov/article/la-malinche-hernan-cortess-translator-and-so-much-more. ↵

- Ryan Purcell, “Life Story: Malintzin (La Malinche) (ca. 1500-1529),” Women & the American Story (blog), accessed April 3, 2024, https://wams.nyhistory.org/early-encounters/spanish-colonies/malitzen/. ↵

- Julee Tate, “Recasting La Malinche’s Role as Symbolic Mother in Eugenio Aguirre’s Isabel Moctezuma,” Hispania 102, no. 3 (2019): 397–408, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26867509. ↵

- “Cultural Insight: Woe Is the Malinchista,” November 2, 2023, https://www.mexperience.com/woe-is-the-malinchista/. ↵

- Farah Mohammed, “Who Was La Malinche? La Malinche was a key figure in the conquest of the Aztecs. But was she a heroine or a traitor? It depends on whom you ask.” JSTOR Daily, March 1, 2019, https://daily.jstor.org/who-was-la-malinche/. ↵

- Ann McBride-Limaye, “Metmorphoses of La Malinche and Mexican Cultural Identity,” Comparative Civilizations Review 19 no. 19 (1988). ↵

- Andrea Penman-Lomeli, “Consuming La Malinche, Destroying the Myth,” The New Inquiry (blog), February 9, 2017, https://thenewinquiry.com/consuming-la-malinche-destroying-the-myth/. ↵

- Octavio Paz, “The Sons of La Malinche,” in The Mexico Reader: History, Culture, Politics edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Timothy J. Henderson, (New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2022), 22-29, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478022978-009 ↵

- Tether A Campbell, “A Victimized Woman: La Malinche,,Historia, Vol. 13, (2004): 37-39. ↵

- Lisa Nevárez, “‘My Reputación Precedes Me’: La Malinche and Palimpsests of Sacrifice, Scapegoating, and Mestizaje,” in Xicoténcatl and Los mártires del Anáhuac” (2004). Decimonónica. Paper 67: 80-81, https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/decimononica/67 ↵

Tags from the story

Conquistadors

Doña Marina

Hernán Cortés

La Malinche

Malinal

Nomination-Political-History

Recent Comments

Luis Ramirez

A very well-written article. Upon starting to read this article you did a good job of introducing who the mother of all Mestizos Is. You also do a good job of explaining how she was sold into slavery to Cotres and that she would help him and translate for him as Cortes waged war in the New World. You did an amazing job of drawing emotion because for one she was sold by her own people and two even though she was with Cortes it was not an equal relationship. None the less a very well-written article.

23/04/2024

8:32 am

Vianna Villarreal

Very interesting and well developed article. I have been so lucky to have learned Spanish history and I think it is so important especially being Mexican-American to learn about the time of spaniard conquering and the struggles of adapting. This extraordinary woman was praised for being educated and being able to communicate with the conquistadores. Very informative article I enjoyed the topic and it was very interesting to read.

24/04/2024

8:32 am

Ana Barrientos

Hi Neyma! First and foremost I like the way you structured your article, and it was very informative and flowed nicely. You told her story very well, I personally have heard about La Malinche, she is a huge controversy in Mexico and I’ve heard people use her name as an insult to others as another way to say you’re a traitor.

22/04/2024

8:32 am