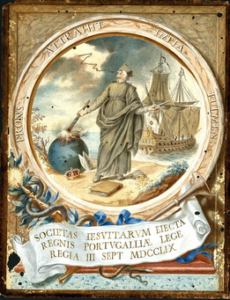

On September 3, 1759, one year from a near fatal attempt on his life, King Joseph I declared that the Society of Jesus would be expelled from Portugal and all its territories. This act created a domino effect in Europe to the detriment of the Society and led to its 41-year suppression within the Roman Catholic Church. But how could a group with exceptional missionary skills and close ties to the pope come under such immense scrutiny that it would lead to banishment? The answer seems to lie with the Marquis de Pombal.1

Born in the small village of Soure in the Coimbra district of Portugal in May 1699, the infant later known as the Marquis de Pombal was given the name Sebastiao Jose de Carvalho e Mello. Inspired by the Age of Enlightenment, he began his early studies at the University of Coimbra. After a brief period in the army, he returned to his studies of history, politics, and legislation at the Academia Real da Historia Portuguesa. His uncle, Paulo de Carvalho, recommended Sebastiao’s service to Portugal’s Prime Minister, Cardinal Joao de Mota. This proved to be a career-opening opportunity.2

Carvalho’s first royal task from King John V in 1733 was to undertake the documentation of the history of the Portuguese monarchs. However, in the same year that his talents were attracting government attention, he found himself married to Teresa Maria de Noronha e Almada, a widow and niece of the Count of Arcos. They moved to his family property in Coimbra where he continued his studies and tended the land. However, after about five years, his desire for a more distinguished life grew, and they returned to Lisbon.3

In 1739, King John V appointed Carvalho as an Ambassador to Britain, and, thus, he began his career as a statesman. His years of diplomatic service allowed him to study English history, their constitution, and their legislation. He observed the court of King George II, as well as England’s economic, social, and political practices, and he avariciously read works from the Duke of Sully and Cardinal Richelieu. His ambition was inspired by these men, secretly coveting to be a ruler of kings. His reputation and success in England spread farther than it had at home. Upon his return to Lisbon in 1745, he was almost instantly dispatched to Vienna to arbitrate a delicate affair between the Vatican and the Holy Roman Empress Maria Teresa. During Sebastiao’s service abroad, he was exposed to anti-Jesuit sentiments through the royal courts of Britain and Vienna. There was much discussion of the Society’s increasing wealth, control over education, and independence from local laws and from crown rule.4

While managing the negotiations and the concessions at the Vienna court, Sebastiao received news that his wife was dead. He continued his duties to all parties’ satisfaction, but carried grief in his heart. While he continued his service as Ambassador to Austria, the Empress introduced him to her court, and he won the affection of the Countess Leonore Daun. After receiving the blessing of her family and of the crown, the two wed in ceremonial elegance and splendor at Vienna. Carvalho continued his service in Austria until early 1750, just prior to King John V’s death.5

As King Joseph I ascended to the throne in Portugal following the death of his father, he wasted no time to appoint the Carvalho as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. This was the commencement of his reign and domination in politics that would last until the King’s death in 1777.6 Seen as a relatively weak monarch, King Joseph relied heavily on his ministers. Carvalho quickly gained the confidence of the king and rose in influence over state politics and economic reforms. Proceeding with care as to not provoke opposition from nobility and clergy or lose favor with the king, Sebastiao began his ministry to save Portugal. Pombaline reforms, as they would be later called, targeted progress to increase Portugal’s self-sufficiency. As a relatively small country, Portugal relied heavily on Britain for manufactured goods and one of its main colonies, Brazil, for economic support throughout King John V’s reign. The fruits of Carvalho’s career were seen in the growth of the navy, revived trade, agriculture and industrial progress, and increased revenue.7

However, Carvalho held much contempt for the nobility and for the Society of Jesus. He felt threatened by their aristocratic order, their close ties to the pope, their control of education, and their independence from the crown. His Anti-Jesuit campaign found crucial aid in his brother Francisco Xavier de Mendonca Furtado, a colonial governor in Brazil, his cousin Almeida e Mendonca, ambassador to the Vatican’s curia, and Bishop Dom Miguel de Bulhoes of Brazil. Together, they launched a propaganda war full of conspiracy theories, and they boasted the hypocrisy and extravagance of the holy order.8

An early targeted area for his anti-Jesuit campaign was Jesuit missions in Brazil known as reductions. Because the Jesuits in South America built up their own autonomy, Carvalho resented their independence and wealth. He viewed the Society as a direct opposition to growth and prosperity in Portugal and Brazil. Following the Treaty of Madrid in 1750, it was also believed that the Jesuits aided the local native Guarani tribes in resisting relocation between Spanish and Portuguese territory by provided them with weapons and fighting alongside the indigenous people.9

Tensions between the Portuguese crown and the Society continued to build. On All Saints Day 1755, the great Lisbon earthquake shook more than the ground. The earthquakes, tsunami, and fires devastated three quarters of the city. The devout victims were terrified and implored their Lord’s help and salvation. In the aftermath, some religious figureheads, like the Italian Jesuit missionary Gabriel Malagrida, were viewed as exploiting the situation and the religiously devoted.10 Malagrida claimed the earthquake was retribution and punishment for the past and present sins of the city’s citizens. However, Carvalho made his presence known to the people of Lisbon to create order, discipline, and triage. He expressed that the cause of the earthquake had nothing to do with God and explained the situation as the earth’s interior exhaling.11

Following the earthquake, the King developed severe claustrophobia and bestowed even greater authority to Carvalho. With the king’s withdrawal, Sebastiao’s level of power grew to a new height, and the tension with the nobility and the Jesuits reached a crescendo. In September of 1758, King Joseph was almost fatally wounded in an assassination attempt. While returning from an evening with his mistress, the king’s carriage was ambushed. Carvalho wasted no time and established a tribunal to investigate the Tavora Affair as it would become known, because the accused conspirators were the Tavora family. The royal commission targeted Luis Bernardo de Tavora, his wife and sons, the Duke of Aviero, Malagrida and other Jesuits.12

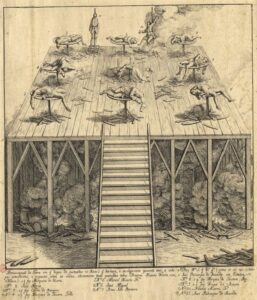

Following this inquisition and a confession by Aviero, who found issue with Carvalho’s anti-nobility reforms, about sixty people were convicted. The Duke of Aviero had letters noting that, in order “to destroy the authority of king Sebastian, we must annihilate that of King Joseph.”13 Carvalho sentenced the Tavora family and the Duke of Aviero to death – they were either decapitated, burned alive, or strangled and bound up on the wheel. Since Malagrida was the personal confessor for the Tavora family, the royal tribunal implicated the Jesuits, stating that they had had a hand in the assassination attempt as well.14

Following the Tavora affair in January 1759, the long-standing tensions between the crown and the Society of Jesus reached its boiling point. Claiming that there were close ties between the conspirators and the Society, and that religious enthusiasts were instruments of ambition, dozens of Jesuits were placed under house arrest. Carvalho also began sequestering all Jesuit holdings, real and personal, in Portuguese territories, including reductions in Brazil. Convinced the kingdom would not know peace or prosper while the Jesuits remained in Portugal, he wrote to Pope Clement XIII in April 1759 to express the issues at hand. He claimed the Society’s principles and doctrine were too dangerous for Portugal’s safety and that the order had slipped away from the foundations on which it was instituted. He continued to list Jesuit infractions against the nation and the church.15 Then, in September, one year following the assassination attempt of King Joseph, the Jesuits were officially suppressed and expelled from Portugal. The state seized all Jesuit land, estates, and other assets. Anyone attempting to defy the crown’s authority on this matter was jailed and some were even executed, including Jesuit missionary Malagrida who was burned at the stake in 1761.16

Carvalho’s clash with the Society of Jesus bolstered his pride and ambition. He was able to topple an established holy institution. The seizure of assets and properties enriched the royal crown. For Sebastiao, a man greatly influenced by the Enlightenment, the expulsion and suppression of the Society fit into his larger plan to eliminate Catholicism and degrade the Holy See to show how it was powerless in domestic affairs. His impact went far beyond the boundaries of Portugal and held territories. This would mark the beginning of a tidal wave of expulsion and suppression of the Society of Jesus from other European nations. Following these expulsions from France, Spain, Parma, and Poland, the papacy was under considerable pressure to find a solution alongside these kingdoms. Seen as the only way to bring peace, Pope Clement XIV formally suppressed the Society of Jesus in 1773.17

Carvalho was rewarded by King Joseph with an additional title, Count of Oeiras following his dutiful handling of the Tavora Affair. In 1770, the official promotion to Marquis de Pombal was added, and he continued to effectively control Portuguese affairs until King Joseph I’s death in 1777. Following King Joseph I’s death, his eldest daughter Queen Dona Maria I would succeed to the throne. Having been educated by the Jesuits, she loathed Pombal and swiftly forced him out of office. Though he was no longer in control of affairs in Portugal, his legacy had been strongly established.18

- Robert Maryks Lectures on “The Jesuit Suppression,” 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7oR0pbjhuA. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 38-41. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 41-42. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 42-49. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 49-55. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 56-57. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 61-63. ↵

- Dale K. Van Kley, Reform Catholicism and the International Suppression of the Jesuits in Enlightenment Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 151-152. ↵

- James Lockhart and Stuart B Schwartz, Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 383-392. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 85-90. ↵

- Dale K. Van Kley, Reform Catholicism and the International Suppression of the Jesuits in Enlightenment Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 152. ↵

- Dale K. Van Kley, Reform Catholicism and the International Suppression of the Jesuits in Enlightenment Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 154-155. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 196. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 197-206. ↵

- John Athelstane Smith, Esq, Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal, Volume I (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1843), 217-222. ↵

- Dale K. Van Kley, Reform Catholicism and the International Suppression of the Jesuits in Enlightenment Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 155. ↵

- Robert Maryks Lectures on “The Jesuit Suppression,” 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7oR0pbjhuA. ↵

- Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “Marquis de Pombal | Biography & Facts | Britannica,” October 28, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marquis-de-Pombal. ↵

12 comments

Sudura Zakir

In the 18th century, the Marquis de Pombal was crucial in the Jesuits’ expulsion from Portugal and its territories. Pombal was a divisive personality, well known for his autocratic behavior and modernizing policies for Portugal. At the time, his actions toward the Jesuits drew sharp criticism, but they were also considered as an essential step in strengthening the Portuguese monarchy. Although Pombal’s legacy is still up for debate, there is no denying his impact on Portuguese history.

Zachary Kobs

This article was really intriguing, and there were a few things that stood out to me. One of the big takeaways is how much political power and influence can shape history. The Marquis de Pombal was this guy who became really important in Portugal, and he used his position to basically kick out the Jesuits and suppress them for over 40 years. The article talks a lot about how Enlightenment ideas were really influential at the time and how people like Pombal were using their new knowledge to try and change things in their country. But it’s also important to recognize that he and his allies were using some pretty sketchy tactics, like propaganda and scapegoating, to turn people against the Jesuits. It makes me wonder about the role of ethics in politics and how we can make sure people are using their influence for good. Congratulations on your nomination!

Aaron Astudillo

Hey Barbara, congratulations on the nomination. As a political science major, this article definitely captured my attention as it goes in-depth to the politics that goes within all the different aspects of society. Thus, the article of Marquis de Pombal and his impact on history is excellently written and the Jesuit Society.

Maximillian Morise

This is an amazingly detailed article about the politics within the Roman Catholic Church, in European society, and how it affected people of all walks of life. I had never heard of the Marquis de Pombal before now, but now I understand the sheer effect that he had on the Jesuits as a whole. Congratulations on your brilliant article, and your nomination!

Jared Sherer

The detail in this article is amazing. I had not heard of the Marquis de Pombal before reading this article, but it is an intriguing subject. I believe I will delve further into this historical figure because of this article. Circumstances and hard work took Carvalho far in his career, along with knowing and impressing the right people. It is ironic that, after a life of going against the Jesuit Society, immediately after his death, the Society started to regain its stature. This is an interesting topic that I may research further. Very well written and the images are first rate as well.

Abbey Stiffler

It’s wonderful that there was so much documentation of the Marquis de Pombal. On September 3, 1759, one year after a nearly catastrophic try on taking his life, King Joseph I declared that the Society of Jesus would be expelled from Portugal and all its territories. This caused a chain reaction in Europe to the Society’s disadvantage and resulted in its 41-year suppression within the continent. Congrats on the nomination!

Luke Rodriguez

This was a fantastic read! Also, congrats on the nomination! It was well-deserved. The article was well-written and detailed. The way this article was formatted was also incredible and kept me wanting to read line after line. I have no complaints about this article, which has a well-deserved nomination.

Nnamdi Onwuzurike

Congratulations on your nomination! The Marquis de Pombal played a pivotal role in the expulsion of the Jesuits from Portugal and its colonies in the 18th century. Pombal was a controversial figure, known for his authoritarian style and reforms aimed at modernizing Portugal. While his actions towards the Jesuits were harshly criticized at the time, they were also seen as a necessary step in consolidating the power of the Portuguese monarchy. Pombal’s legacy continues to be debated, but his influence on Portuguese history is undeniable.

Guiliana Devora

This is an amazing article and the author did an incredible job of telling it. Congratulations as well for the nomination of Best Publication in the Humanities. The way this article was formatted was incredible as well and it kept me wanting to read line after line. I have no complaints about this article and this article has a very well deserved nomination.

Marissa Rendon

What an interesting article this was! By far one of the most interesting articles I have definitely read. I love the images you used. The images that were used throughout the article truly put this piece together. I hope you are proud of your work because this article was excellent!