“But where is he? He isn’t coming, he won’t show up, he won’t come.” These words spilled out of the mouth of a Dominican priest, though the same variations of these words were echoing throughout Worms. No one believed that Martin Luther, the bold monk had enough gall to show his face when many such as him were being brutally executed. In Luther’s own words, “We shall enter Worms despite the gates of hell and the powers of darkness.” And that is just what he did.11

Those who were in Worms, who witnessed Martin Luther’s entrance into the city, described it as Jesus coming into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. Crowds of people gathered to see the stoic monk, unwavering, not a sign of fear painted his face. Roper states, “When he arrived at Worms on April 16, two thousand people thronged the streets trying to get a look at him.”12 There are accounts of a monk who stepped forward as Luther was exiting his wagon; the monk stepped forward and embraced Luther, proceeding to touch his simple black robe three times, as if he were a saint. When the time came, the spring afternoon of April 17, it was time for Luther to face the wolves. The press of people waiting to catch a glimpse of Luther stared in awe, in Roper’s records “Many climbed to the rooftops in their eagerness to see,” stated an observer.13 Many stared curiously at the man so strong and stoic with no fear in his eyes as he walked into the Diet. Luther passed princes and nobles who crowded into the room and were all dressed in their finest cloaks, golden chains, and jewelry. Luther stood in stark contrast against the finery of the court, his plain appearance symbolic of his views.

Inside the Diet, Luther had a brief rundown of what was going to happen. Luther would receive a line of questioning, where he would be asked to recant his teachings. The humble monk was led into the courtroom. In front of him was a bench and a pile of his books. “Let the titles of the books be read!” exclaimed the professor of law at Wittenberg who was acting on Luther’s defense. The extraordinary list of Luther’s works was read off to the nobles and the emperor. All that was expected of Luther’s answering was a simple yes or no, his voice, barely audible in the vast, grandiose room. Luther was asked if these books belonged to him, and whether he would recant his teachings and be reconciled with the Church. Pondering this question, he responded: “Because this is a question of faith and the salvation of souls, and because it concerns the divine Word, which we are all bound to reverence, for there is nothing greater in heaven or on earth.”14 He went on to say that it would be”rash and at the same time dangerous for me to put forth anything without proper consideration,” he then requested a recess, and for the Diet to be continued the next day.

Luther now had a second opportunity to speak, returning the next day. Luther had one strategy, to insist his argument be heard, and the Diet gave him the perfect stage to argue his beliefs. On April 18, Luther was met with an even larger audience with some of the nobility even forced to stand, and a hushed anticipation coated the air. The room was shrouded in a candle-lit glow, Luther standing tall against the backdrop of many curious eyes. Questions from the day before were again recited. In his new reformed answer, Luther again acknowledged his books, he also acknowledged the variety of topics he covered in his literature, with unwavering clarity. In some of his teachings, he preached God’s Word in its simplest form, in others he attacked the teachings of the Holy Roman Catholic Church. Luther spun an elaborate speech detailing his beliefs and teachings, tantalizing the court with the image of a relationship with God without corruption. Luther concluded his speech with the now famous words:

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise. May God help me. Amen.”

These words encapsulated the spirit of his speech, the essence of his being, and the face of the Reformation.

The tapestry that is sixteenth-century Germany is woven with the intricate threads of religious, political, and cultural forces that merged to create the complex political entity that was the Holy Roman Empire, with the church being a key figure in that ever-changing European landscape. Catholicism, being the dominant religion of the time, was deeply intertwined into the fabric of the German government. The Holy Roman Church was made up of a complex hierarchy of power, with much of it being in the hands of the pope. Corruption infested the church, and the sale of indulgences—a practice that offered salvation in return for earthly wealth—fueled discontent in the church. This practice of selling indulgences set the perfect scene for Martin Luther, a humble monk whose mission, “Out of love and zeal for the truth,” challenged the corrupt ideology of the church, and provided hope for those seeking a true and genuine connection with God.

These words echoed throughout the halls of Wittenburg Castle and were whispered throughout the court of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1520. For Martin Luther, his fate was set in the parchment letter that would determine his fate. This piece of parchment was an invitation summoning him to a lion’s den. The edict was a proclamation from the highest levels of authority, the Roman Catholic Church and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, a last-ditch effort to stop the spread of the theological wildfire Luther had sparked through his 95 Theses. The humble monk would have to fight for everything he believed in. Failure meant death, a fate that had been suffered by many before him who had been similarly summoned and met their certain death.

Before we delve into our story, we must set the scene. Barbra Stollberg-Rilinger in her book The Holy Roman Empire: A Short History described the empire this way: “While it existed, the Empire was most commonly imagined as a loose political body. It contained very different members or ‘limbs’ that formed individual ties to a common overlord, or ‘head’ (the emperor), through oaths of personal fealty.”1 This structure fostered a sense of unity all while allowing for regional autonomy, which created a unique political dynamic. The Holy Roman Empire was not only a political body, but also a spiritual one, with the Pope, and the church at the forefront of much of the politics, with the Papacy’s influence deeply intertwined in the fibers making up the Holy Roman Empire. Stollberg-Rilinger relates this about the empire: “According to an often-quoted quip by the eighteenth-century French philosopher Voltaire, the Holy Roman Empire was neither Holy nor Roman, nor indeed an empire at all.”2 The term “Holy” implies a spiritually focused and secure nation, “Roman” alluded to a historical legacy, and “Empire” suggested an integrated political body. The empire’s lax political structure, combined with its spiritual influences, created a dynamic where authority was dispersed among different political entities. This dispersion of power allowed for regional differences that defied the conventional expectations of centralized empires. The one common theme uniting the empire is the strong Catholic faith.

However, despite the façade of unity, the Holy Roman Empire was overflowing with internal strife. The intertwining of spiritual and political authority laid the groundwork for corruption within the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church defines the sale of indulgences as “a remission before God of the temporal punishment due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven, which the faithful Christian who is duly disposed gains under certain prescribed conditions through the action of the Church which, as the minister of redemption, dispenses and applies with authority the treasury of the satisfactions of Christ and the Saints.”3 Put in more modern terms, the sale of indulgences was the widespread practice where forgiveness for sins, as well as the reduction of one’s time in purgatory, could be purchased. Charismatic preachers, often associated with the Catholic Church, milked money from individuals, where the money then flowed into the lucrative pockets of the Holy Roman Catholic Church. These funds fueled the construction of extravagant churches and monuments, like St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, as well as the pockets of the “holiest” members of the Papacy. This practice of selling forgiveness with earthly contributions contradicted the fundamental theological teachings of the holiest text, the Holy Bible. The church’s hoarding of wealth through these indulgences and the Pope’s authority to grant indulgences challenged all that was known of spiritual authority.

The discontent that set root in these corrupt practices sowed the seeds of discontent across every corner of the Holy Roman Empire. The social and political landscape that was the Empire was awash with tension as the people fought a moral battle against the sale of indulgences and the abuses of power. This tumultuous environment set the stage for Martin Luther, a humble man of humble origin, to emerge as one of the most formidable figures of the time.

Martin Luther was born to humble beginnings, on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Germany. Luther was born the son of peasants and spent much of his early years growing up in a mining town. Luther grew up seeing the injustices the mine owners enacted on its workers and, in the words of historian Lyndal Roper, these “bitter experiences shaped Luther’s economic thought.”4

After his early childhood years, the Luthers made a huge financial sacrifice and sent their oldest of seven children, Martin, on his path to acquiring an education, and his academic journey eventually led him to continue his studies at Erfurt University in 1501. Lyndal Roper notes that Luther described the university as a “whorehouse and beer house; these two lessons are what students got from that gymnasium.”5 Around 1505, he then completed his studies at twenty-two years old with his Master of Arts, whereafter his father pushed him to study law. Luther seemingly had everything laid out for him, going into studying law. Roper explains that Luther’s family was keen on Luther “marrying into the local elite of the mine owners … and use his knowledge to advance his family’s interest.”6 Luther seemed to be quickly headed to the top, into the lifestyle his family always dreamed for him. But that is not what happened.

An unfortunate series of events played a massive role in creating the Martin Luther who changed history. A friend of Luther’s fell ill and passed away shortly after graduation, and his death deeply affected him. Roper explains that the death of Luther’s companion “appears to have plunged him into melancholy.”7

Luther also suffered a grave injury while traveling after mishandling his sword, slicing his leg, and causing it to swell to unnatural proportions. It was said that while Luther was experiencing his medical emergency, he cried out “O Mary, help!” and a doctor was summoned to treat his wound. Though later that night they would burst and again he called out to Mary to save him, and in the morning his wound had healed, appearing as though Mary had saved him.

The biggest and most momentous event happened while Luther was journeying back to Erfurt to meet his family. On July 2, 1505, Luther, while riding on horseback, found himself flung into a roaring thunderstorm. Luther dismounted his horse and was enveloped in the whipping winds and pouring rain with the loud cracks of lightning echoing in his brain. Most of those who encountered thunderstorms such as these seldom made it out alive. A bolt of lightning zapped the ground inches away from Luther, and he screamed out in terror “Hilfe mir, Sankt Anna!” (“Help me, Saint Anne!”) and the word he said next became a promise that shaped the whole trajectory of his future. “Ich will ein Mönch werden!” he shouted, “I want to become a monk!” He lived that day, and as he shrieked in the solemn vow he made to Saint Anne, he became a monk.

After this pivotal moment, Luther kept true to his vow and devoted his life to Christ. This event became the catalyst that kickstarted Luther on his journey to become closer to God. On July 17, just two weeks after the storm, Luther was accompanied by his closest friends to the doors of the Augustinian cloister of Erfurt. The Augustinian Order of Monks, which is officially known as the Order of Saint Augustine, was created in the thirteenth century. This group emphasized a communal life of prayer, service, and study. Luther continued in his pursuit of a closer and more authentic relationship with God.

Later on, in 1508, Luther was appointed to fill a position as professor at Wittenberg temporarily. This teaching position provided Luther the opportunity to practice and facilitate public discussions on the theological issues of the time. Luther was admired among his students and soon became well-regarded throughout the school.

Indulgences were pardons granted by the church that claimed to reduce the punishment that would be received in the afterlife due to the consequences of one’s mortal sin. These indulgences were marketed by the preacher Johannes Tetzel, a preacher who began the sale of indulgences in 1508. Roper relates that Tetzel took his newfound idea straight to “the mining region of St. Annaberg, named after the miner’s saint the mother of the Virgin Mary: Miners needed all the protection they could muster.”8 The Lutheran preacher of the town, Myconius, was recorded to have said later about Tetzel: “If they just put in the money and bought grace and indulgences, all the mountains around St. Annaberg would become the purest silver; and as soon as the coins clinked in the bowl the soul for whom they had put it in would fly straight to heaven with their dying breath.”9

Luther argued that salvation could not be bought through earthly wealth and that forgiveness from God came from repentance of one’s sins, which was accepted by faith alone (sola fide), which was not exactly the ideology of the Roman Catholic Church. Martin Luther’s criticism of the sale of indulgences was put into writing in his Disputation on the Power of Indulgences commonly known as the 95 Theses. Within Luther’s Theses, he scrutinized the authority of the Pope to grant indulgences, as well as the sale of the indulgences themselves. Luther asserted that the Bible, not the authority of the church or tradition, was the ultimate source of true religion (sola scriptura). Luther used scripture to attack all of the Church’s wrongdoing, such as criticizing the Church for hoarding earthly wealth when the Bible states that true wealth comes from spiritual grace, not material riches. Luther continued in his Theses by challenging the authority of the church hierarchy and urging Christians to live a life devoted to God rather than seeking salvation through monetary wealth.

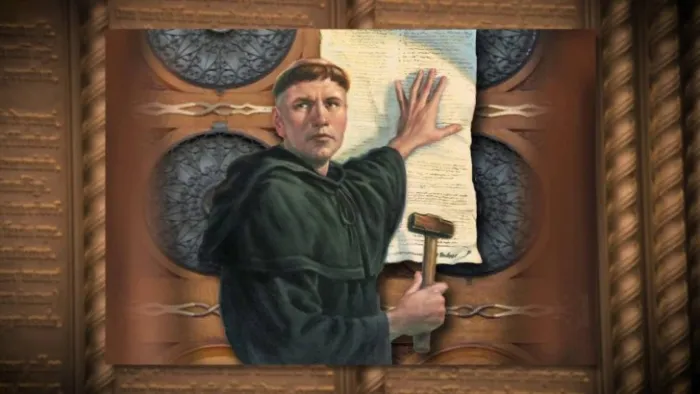

Attaching documents to the doors of the Wittenburg Castle Church was the equivalent of posting an announcement onto a bulletin board. Luther attached his Theses to the Wittenburg doors for all to see, and many did indeed see. The 95 Theses gained much traction among the educated student body, sparking discussions and debates among a multitude of academic and theological circles. Many students embraced Luther’s ideas and eagerly absorbed his writings and teachings. Luther’s message spread like wildfire in universities all across the vastness of the Holy Roman Empire. Luther’s ideas captivated the minds and hearts of the younger and reform-minded generation of scholars who were eager to challenge the traditional orthodoxy and pursue a more authentic practice of faith.

Luther’s Theses were not only nailed to the doors but also taken down and circulated among young scholars. Luther mailed his Theses to three religious figures. The Archbishop was one of the most powerful religious figures of the time. Luther’s Theses traveled through the hands of the Archbishop, who forwarded his Theses to the Pope. Luther also sought the opinion of the members of his theology department for their thoughts, which is a tradition when reviewing ideas put forth by professors who questioned church doctrine. These Theses became the catalyst of the Protestant Reformation, many of whom supported his teaching and came from among the common people. Luther advocated for a more accessible and more direct relationship between individuals and God (a “priesthood of all believers”).

Another of his key supporters was Fredrick the Wise of Saxony, the founder of the University of Wittenberg where Luther taught. Although the two did not interact much at the University, Fredrick believed that Luther was being unfairly attacked by Church officials, and went on to be one of Luther’s biggest supporters. Although many of the common people agreed with Luther’s teachings, he nevertheless faced much criticism. The church fought hard against what the pope described as the heretical teachings of Luther by sending out religious figures to oppose Luther’s teachings. Most of those who disagreed with his teachings were in great positions of power in Germany and the Roman Catholic Church. These powerful figures detested Luther’s teachings due to the social and economic impact of what he preached. Gorplam Aleandro was one of the many figures sent out by the pope to counter Luther. Aleandro took part in many debates and discussions attempting to persuade other scholars to reject Luther’s ideas.

After Luther’s Theses circulated throughout much of the Holy Roman Empire, the papal authority knew that they had a problem on their hands. Luther’s teachings challenged many of the practices, traditions, and rituals of the church. After the Leipzig debate, which was another one of Luther’s notorious debates over doctrine, Pope Leo X swiftly decided that the time had come to take action against Luther. Luther was then summoned to appear in Rome to account for his teachings, through the “Exsurge Domine.” This was a papal bull that was issued by Pope Leo X, on June 15, 1520, which was a response to the comments and teachings in Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. In this document, the pope condemned Luther for “41 distinct errors” in his 95 Theses. In this decree, the Pope gave Luther sixty days to recant his so-called errors publicly in Rome or face automatic excommunication. Three and a half years had passed since the publication of the 95 Theses, and Luther knew his life was at stake. With the weight of sixty days hanging over him to recant his teachings, Luther knew his time was running out. Being summoned to Rome to “answer for his views” was a death sentence. Many times in history, many who had challenged the thinking of the Roman Catholic Church had been executed due to the conclusions of the trials held, such as that of Jan Hus in Prague just one hundred years earlier. Despite knowing the risks at hand, Luther had no intention of making the journey to Rome, despite the protest among the religious officials who wanted to squash the change coming. As the months came and went, the papal authority got more and more frustrated with the humble monk.

The sixty-day timer came to an end on December 10, 1520, and the brisk winter morning was illuminated by a raging fire. The cool morning air was thick with anticipation, The students and teachers of the University of Wittenburg gathered by the town gate, circling a roaring fire. The members of the university poured the books of Luther’s rivals into the open flames. Hundreds of books pouring in, fueling the fiery inferno. Martin Luther himself stepped toward the flames, his figure illuminated against the backdrop of the early morning, and with a steady hand, tossed the papal bull into the fire, watching it burn—a revolutionary act, showing the pope that Luther would not bow down to his authority any longer.

Two weeks after his fiery act of defiance, Luther was officially excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church. All eyes turned to Charles V, the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Pope Leo urged the emperor to take action against Luther as soon as possible. However, the young emperor, who was only twenty at the time, refused to condemn any German citizen without giving them a chance to defend themselves in court.

Thus, on March 29, 1521, a message adorned with the sign of the imperial eagle was sent carrying the “Imperial Safe Conduct.” This document held the promise of a safe passage to the Diet that would be held in Worms. There, Luther was being summoned to recant his teachings. Luther had expected this. What he did not expect was an important official of the Holy Roman Empire, which seemed, according to historian Kenneth Appold, “a kind of victory for the Reformer. Rome had desperately sought to avoid such a scenario for it undermined the authority of its own supposedly definitive actions against Luther and ceded authority to a secular process whose outcome it would be at pains to control.”10 Luther’s journey to Worms became a proud procession for his cause, with many people following him as he made his trek to the city of Worms. Crowds gathered everywhere Luther journeyed, and an atmosphere of anticipation followed him like a cloud. Luther was not the only one to journey to Worms. It was the spirit and soul of reform itself, walking hand in hand into the lion’s den.

“But where is he? He isn’t coming, he won’t show up, he won’t come.” These words spilled out of the mouth of a Dominican priest, though the same variations of these words were echoing throughout Worms. No one believed that Martin Luther, the bold monk had enough gall to show his face when many such as him were being brutally executed. In Luther’s own words, “We shall enter Worms despite the gates of hell and the powers of darkness.” And that is just what he did.11

Those who were in Worms, who witnessed Martin Luther’s entrance into the city, described it as Jesus coming into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. Crowds of people gathered to see the stoic monk, unwavering, not a sign of fear painted his face. Roper states, “When he arrived at Worms on April 16, two thousand people thronged the streets trying to get a look at him.”12 There are accounts of a monk who stepped forward as Luther was exiting his wagon; the monk stepped forward and embraced Luther, proceeding to touch his simple black robe three times, as if he were a saint. When the time came, the spring afternoon of April 17, it was time for Luther to face the wolves. The press of people waiting to catch a glimpse of Luther stared in awe, in Roper’s records “Many climbed to the rooftops in their eagerness to see,” stated an observer.13 Many stared curiously at the man so strong and stoic with no fear in his eyes as he walked into the Diet. Luther passed princes and nobles who crowded into the room and were all dressed in their finest cloaks, golden chains, and jewelry. Luther stood in stark contrast against the finery of the court, his plain appearance symbolic of his views.

Inside the Diet, Luther had a brief rundown of what was going to happen. Luther would receive a line of questioning, where he would be asked to recant his teachings. The humble monk was led into the courtroom. In front of him was a bench and a pile of his books. “Let the titles of the books be read!” exclaimed the professor of law at Wittenberg who was acting on Luther’s defense. The extraordinary list of Luther’s works was read off to the nobles and the emperor. All that was expected of Luther’s answering was a simple yes or no, his voice, barely audible in the vast, grandiose room. Luther was asked if these books belonged to him, and whether he would recant his teachings and be reconciled with the Church. Pondering this question, he responded: “Because this is a question of faith and the salvation of souls, and because it concerns the divine Word, which we are all bound to reverence, for there is nothing greater in heaven or on earth.”14 He went on to say that it would be”rash and at the same time dangerous for me to put forth anything without proper consideration,” he then requested a recess, and for the Diet to be continued the next day.

Luther now had a second opportunity to speak, returning the next day. Luther had one strategy, to insist his argument be heard, and the Diet gave him the perfect stage to argue his beliefs. On April 18, Luther was met with an even larger audience with some of the nobility even forced to stand, and a hushed anticipation coated the air. The room was shrouded in a candle-lit glow, Luther standing tall against the backdrop of many curious eyes. Questions from the day before were again recited. In his new reformed answer, Luther again acknowledged his books, he also acknowledged the variety of topics he covered in his literature, with unwavering clarity. In some of his teachings, he preached God’s Word in its simplest form, in others he attacked the teachings of the Holy Roman Catholic Church. Luther spun an elaborate speech detailing his beliefs and teachings, tantalizing the court with the image of a relationship with God without corruption. Luther concluded his speech with the now famous words:

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise. May God help me. Amen.”

These words encapsulated the spirit of his speech, the essence of his being, and the face of the Reformation.

As Luther’s words of passion echoed through the revered halls of the Diet of Worms, even for those not interested in the theology of the time, Luther’s resistance showed that a humble monk could argue against the strongest powers of the time. As the Diet continued, “Burn him!” echoed throughout the court. Luther was suddenly whisked away from Worms just before his certain arrest, and he was brought to Wittenburg Castle, where he continued to make good on his “priesthood of all believers” teaching by translating the Bible into German, so that each individual might read God’s Word for himself. Luther’s actions spread from Worms and resonated across the continent, his bold defiance toward authority kickstarting the Protestant Reformation, and the waves of his actions forever altered the course of history.

- Barbra Stollberg-Rilinger, The Holy Roman Empire-A Short History (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2018), 11. ↵

- Barbra Stollberg-Rilinger, The Holy Roman Empire-A Short History (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2018), 12. ↵

- U.S. Catholic Church, Catechism of the Catholic Church : Second Edition, 2nd ed (New York: Image, January 1, 1997), 372. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 16. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 32. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 33. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 34. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 17. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 17. ↵

- Kenneth G. Appold, Taking a Stand for Reformation: Martin Luther and Caritas Pirckheimer (Lutheran Quarterly: John Hopkins University Press, March 1, 2018), 40–59. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 167. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 168. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 168. ↵

- Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther : Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, January 1, 2017), 169. ↵