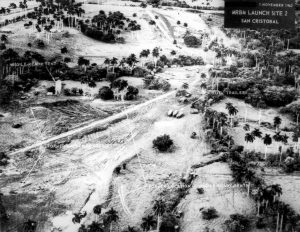

On Tuesday, October 16, 1962, the news of the day did not reach President John F. Kennedy through the newspaper; they were communicated to him with due secrecy by his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy: the Soviets had nuclear weapons on Cuban soil. Two days before, on October 14, a U-2 spy plane of the United States had taken pictures of the Soviets’ missile bases being set up in Cuba. The missiles had a range of 1,300 nautical miles, which made them able to reach Washington D.C. and several US states in a matter of minutes. After receiving this news, Kennedy called the Attorney General of the US, his brother Robert F. Kennedy.1

The two brothers quickly decided that the crisis should be handled by a select committee of advisors: the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or the ExComm. The majority of the members of the Committee were quick to suggest an air strike on the bases before the missiles were operational. However, Robert Kennedy suggested a more diplomatic approach. The Attorney General argued that if they sent military force against the Soviet forces in Cuba, the USSR would feel free to justify a military intervention in Turkey to remove the Jupiter Missiles that the US had placed there, which were there as part of a NATO strategy to deter potential Soviet aggression against Europe and as a deterrent for communism expansion.2

In a race against uncertain time, the ExComm reviewed its options: an air strike followed by a ground invasion of the island, or a naval blockade of the island. Some members of the committee argued that this was the moment to take Cuba away from Castro. Others argued that even if the invasion were successful, the Soviets could bomb the NATO missiles in Turkey, and the US would be obligated to bomb Soviet missile bases in Soviet territory, creating a domino effect of nuclear destruction. The idea of a naval blockade and a more diplomatic approach started to gain strength among the ExComm members, pushed by RFK, who convinced his older brother that diplomacy was a better solution.3

By October 18, President Kennedy had a meeting with the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Andrei Gromiko. The meeting was originally not to talk about the situation in Cuba but to talk about Berlin. However, during the meeting, Kennedy interrogated Gromiko about the possibility that the Soviets had nuclear weapons in Cuba, and the Soviet minister denied it. After the meeting, Kennedy said to some members of the ExComm, “Gromyko ‘told more barefaced lies than I have ever heard in so short a time. All during his denial that the Russians had any missiles or weapons, or anything else, in Cuba, I had the low-level pictures in the center drawer of my desk, and it was an enormous temptation to show them to him.'”4 At that point in the crisis, the USSR was not aware that the US knew about the missiles, which gave the Americans some time to decide their next move.5

After days of deliberation, the ExComm had not come to a decision. After RFK compared the potential air strike on Cuba with the Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor as a war crime, the advice for President Kennedy was to prepare a speech for the American public. The draft of the speech was a way to break down and answer questions for the naval blockade plans. Kennedy handed that responsibility to Ted Sorensen, one of the members of the ExComm, to draft a speech to help him and the ExComm clarify their thinking. The first draft provided a framework of basic policy around which an ExComm consensus could be formed and a presidential decision made. There was also a second draft advocating for the air strike. Ted Sorensen, who was in charge of drafting the first speech, found this draft many years after the crisis: “I have ordered–and the United States Air Force has now carried out– military operations with conventional weapons to remove a major nuclear weapons build-up from the soil of Cuba.”6 Although it is not known who the author of this draft was, what is known is that if the US had sent an air strike on Cuba, the Soviet forces were authorized to use nuclear weapons, making the air strike the beginning of a nuclear war. By Sunday, October 21, the ExComm finally approved the idea of the naval blockade.7

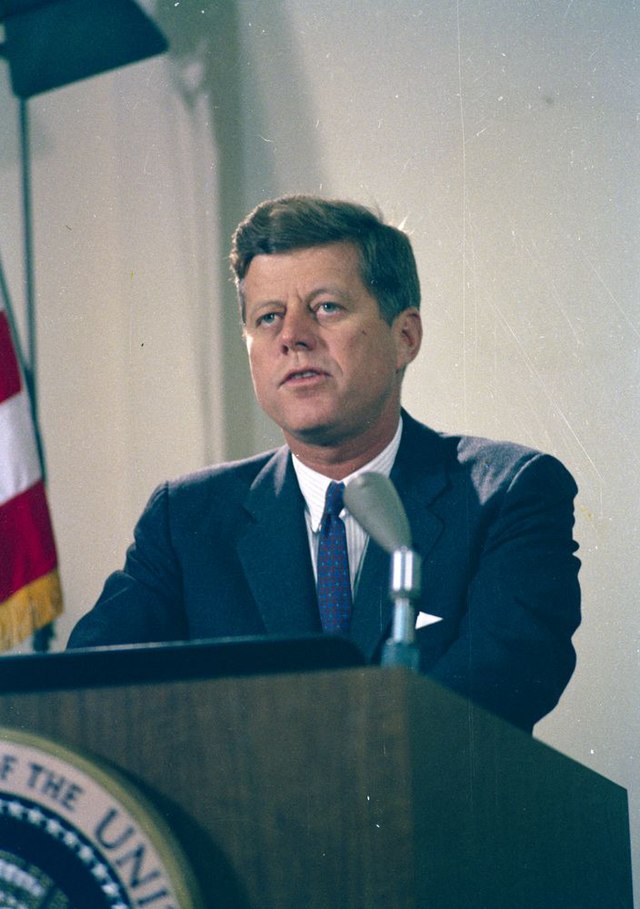

On Monday, October 22, at 7:00 PM, JFK addressed the nation and the world via radio and television. It was pointless to keep hiding the nuclear threat. After six days of intense discernment, Kennedy could not have asked his nation to be united as long as those in charge of deciding the future of the nation were not. JFK then called for a quarantine in Cuba. The US navy had orders to stop any ship that could have any materials that could be used for the construction of nuclear weapons and send them back to their port of origin. In his speech, Kennedy warned the Soviet Union that any aggression against the Western Hemisphere would be considered an act of war. JFK also emphasized that the US would not unnecessarily undergo the risk of a nuclear war: “We will not prematurely or unnecessarily risk the costs of worldwide nuclear war in which even the fruits of victory would be ashes in our mouth.”8 With this message, JFK was not attempting to show off the US military strength but to force the highest authority of the USSR, Nikita Khrushchev, to start diplomatic conversations with the US to stop the crisis. The ball was now in the Kremlin’s court, and it was up to its tenant to prevent the world from plummeting into the abyss of nuclear destruction.9

Shortly after the president communicated the news to the nation, Robert F. Kennedy met with the Soviet ambassador, Anatoli Dobrynin. The Soviet ambassador communicated to Kennedy that the USSR had not sent orders to their ships to change their course from Cuba, telling Kennedy that the Americans were not the owners of the seas. Robert left the meeting worried about the Soviet approach. By Tuesday, October 23, at 10 AM, the naval quarantine on Cuba became effective, but it was not until the news that six Soviet ships had either stopped or reversed their course from Cuba that the blockade was proved efficient. Despite this initial sense of relief, Khrushchev refused to remove the nuclear bases from Cuba, causing the nation’s military apparatus to move to DEFCON 2 (Defense Readiness Condition) for the first time in history. The attempts of the Kennedy brothers and the ExComm to prevent a nuclear war seemed far from their objective.10 The crisis escalated further when, at the United Nations meeting on Thursday the 25th, US Ambassador Adlai Stevenson and his Russian counterpart, Valerian Zorin, had a disagreement. The American ambassador asked Zorin if he denied that the USSR had missiles on Cuban soil; the Soviet ambassador refused to answer. Stevenson then showed him photographs of the military bases in Cuba. When the world seemed to be about to collapse in a Nuclear apocalypse, and the president started to ponder the need for a military invasion of Cuba, a letter from Khrushchev arrived with peace terms. The Soviets would get out of Cuba as long as the US committed to leaving Cuba alone and removed the Jupiter missiles from Turkey.11

However, Khrushchev’s demands arrived on Saturday, October 27. That same day, Soviet forces had shot down a U-2 plane, and the pilot, Rudolf Anderson Jr., died as a result. Anderson became the only fatality of the conflict. As a result, the ExComm met to decide the next step to deal with the crisis. John F. Kennedy said regarding the U-2 plane incident, “There’s always a son-of-a-bitch who doesn’t get the message.”12 The invasion seemed imminent, but it was thanks to the good diplomacy between Robert Kennedy and Dobrynin that it was clarified that the U-2 plane flew in a restricted zone, and there was no need for a military response. RFK, assisted by Sorensen, drafted the response letter to Khrushchev’s demands. RFK urged the ambassador to secure Khrushchev’s acceptance of the proposed terms, warning him that some members of the ExComm were ready to send an air strike on Cuba if necessary. Had the terms been rejected, RFK warned Dobrynin that there would be drastic consequences, although the Attorney General was bluffing with this last part to pressure the Soviets. The news that Khrushchev had accepted the pacific resolution of the conflict arrived early the next day.13

Early in the morning of October 28, 1962, the news arrived: the USSR accepted the peace and the missiles were to be removed in the following days. RFK was the first one to hear the message. Finally, he could feel relieved; his brother and the rest of the nation received the news shortly after. Despite the peace signing lacking typical protocol, where both leaders wore suits, exchanged pens, and shook hands in front of the cameras, JFK soon ordered the U-2 flights over Cuba to stop, and he brought an end to the quarantine, and, in the next six months, they removed the Jupiter missiles from Turkey. The Kennedy brothers could finally breathe again with the rest of the world after thirteen days when the whole world was on the verge of destruction.14

- James Hilty, Robert Kennedy : Brother Protector (Philadelphia, Pa: Temple University Press, 1997), 443-444. ↵

- Jonathan Colman, The Cuban Missile Crisis: Origins, Course and Aftermath (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 71-72. ↵

- Theodore C. Sorensen, Counselor : A Life at the Edge of History, 1st ed. (HarperCollins, 2008), 287-289. ↵

- Jonathan Colman, The Cuban Missile Crisis: Origins, Course and Aftermath (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 79. ↵

- Jonathan Colman, The Cuban Missile Crisis: Origins, Course and Aftermath (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 79-80. ↵

- Theodore C. Sorensen, Counselor : A Life at the Edge of History / Ted Sorensen., 1st ed. (HarperCollins, 2008), 294. ↵

- Theodore C. Sorensen, Counselor : A Life at the Edge of History / Ted Sorensen., 1st ed. (HarperCollins, 2008), 292-294. ↵

- Michelle Getchell, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Cold War : A Short History with Documents, Passages: Key Moments in History (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc, 2018), 83. ↵

- Michelle Getchell, The Cuban Missile Crisis and the Cold War : A Short History with Documents, Passages: Key Moments in History (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc, 2018), 83-84. ↵

- Lawrence Freedman, Kennedy’s Wars : Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam / Lawrence Freedman. (Oxford University Press, 2000), 194-196. ↵

- Ernest May and Philip Zelikow, John F. Kennedy : The Great Crises., 1st ed., vol. 3, The Presidential Recordings (W.W. Norton, 2001), 228-270. ↵

- Theodore C. Sorensen, Counselor : A Life at the Edge of History / Ted Sorensen., 1st ed. (HarperCollins, 2008), 301. ↵

- Theodore C. Sorensen, Counselor : A Life at the Edge of History / Ted Sorensen., 1st ed. (HarperCollins, 2008), 300-303. ↵

- Theodore C. Sorensen, Counselor : A Life at the Edge of History / Ted Sorensen., 1st ed. (HarperCollins, 2008), 303-307. ↵

2 comments

Micaella Sanchez

I found the story of the Cuban Missile Crisis to be particularly important, especially the tension between military action and diplomacy. Learning how close the world came to nuclear war made me reflect on the immense responsibility leaders carry. I admire how JFK and RFK prioritized peace despite the immense pressure. This crisis reminded me of the critical importance of calm, strategic decision-making when the stakes are life and death for millions.

Carlos Flores

This account of the Cuban Missile Crisis is a powerful reminder of the delicate balance between diplomacy and military action in times of crisis. The Kennedy brothers’ ability to navigate the tension with careful consideration and strategic communication saved the world from the brink of nuclear war. Their leadership and courage are truly inspiring—proof that calm, thoughtful decision-making in the face of danger can shape history.