What are memories? Memory is the state or process of sequential encoding, storage, and retrieval 1. The brain processes information learned (encoding), converts this information into a memory bank (warehouse) so that the individual can later pull information from this storage unit. Endel Tulving, a historical figure in describing memory, suggested similar and contrasting differences between two types of memory: episodic and semantic. Episodic memory stores the personal recollection of events at a specific time and place. Semantic memory stores factual information about the world and language without referencing when it was learned 2. Figure 1 depicts the concept by Bird and Burgess (2008) 3 that the hippocampus is vital for long-term episodic memory. An example of episodic memory could be hitting a baseball for the first time.

In contrast, semantic memory could be that Major League Baseball (MLB) is the professional league for baseball players. Episodic memories can be subcategorized into flashbulb memories, memories of vivid moments that are emotionally linked 4. Memory can also be distinguished into limited immediate information, short-term memory, and long-lasting information, long-term memory, as evidenced by amnesia studies 5.

But what happens if we are unable to form new memories? Memory loss is the inability to store or process new memories. Bilateral damage to either of the hippocampus regions of the brain makes it challenging to establish new memories (anterograde amnesia) and retrieve memories before the onset of amnesia (retrograde amnesia) 12. The longer the period of amnesia, the higher the chance of permanent impairment of brain functioning 13. Memory loss tends to be associated with the older population but can also occur in younger people 14. In addition, various conditions and behaviors can lead to memory loss, including drugs and alcohol 15.

There are two types of memory loss: partial and complete. Partial memory loss is limited to events immediately before or after a traumatic event. In contrast, total memory loss, as described by amnesia, is the complete loss of memories from a certain period of time 16. Furthermore, memory loss can also be permanent or temporary (vacillate). Vacillate memory loss occurs when a person slips in and out of being able to remember events accurately 17. Finally, there are multiple forms of memory loss, such as benign senescent forgetfulness, dementia, multiple infarct dementia, depression, and head trauma.

Benign senescent forgetfulness is when memory is affected by most recent events, although this type of memory loss does not affect an individual’s social or professional life 18. One of the features of benign forgetfulness is its selectivity. It affects unimportant facts, such as forgetting one’s wallet at home. In addition, an individual with mild forgetfulness is aware of their deficit and often uses notes as a reminder 19.

Dementia is another form of memory impairment that includes memory loss and other problems like language deficits, lack of visual-spatial skills, and impaired judgment 20. Dementia’s memory impairment affects the brain and interferes with an individual’s ability to have a social or professional life. One of the key facts about dementia is that there is only awareness of the disease in the earliest stage 21. As dementia progresses, disorientation about the time of day further affects a person’s environment. One of the critical differences between dementia and benign forgetfulness is that individuals with early dementia may write themselves notes. Still, they may misinterpret the information or forget to check the reminder 22. An example of dementia would be an individual who needs to pick up groceries and will write a note as a reminder to pick up groceries. However, this individual would continuously pick up groceries because they may have forgotten that this task has already been fulfilled. In addition, people with dementia are often disoriented by their time and environment, leading them not to recognize other people, especially people they should know. This can be difficult for families and caregivers 23. In the latest stages of dementia, a person may not even recognize their own reflection.

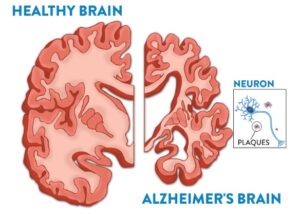

One of the most common forms of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease. Laakso et al. (2000) suggest that in individuals with Alzheimer’s, there seems to be an accelerated rate of hippocampal volume loss 24. However, when this study observed hippocampal loss after the three-year follow-up, there was no improvement in diagnostic accuracy for patients having Alzheimer’s 25. As seen in Figure 2, a brain affected by Alzheimer’s, has a shriveled-up cortex. This damages the neuronal connections typically, allowing neurons to travel and send signals throughout the brain.

Depression can cause memory impairment due to problems that relate to attention and concentration 33. Depression correlates with dementia, making differentiating the two memory impairments difficult. One of the primary differences between depression and dementia is that people with depression are almost always aware of their memory deficit and are moderately distressed 34. People with dementia are unconscious of their memory deficit and not in distress, except in the early stages of dementia 35. Characteristics of people with dementia include their ability to express stable emotions compared to people with depression who lack enthusiasm, interest, and concern. Individuals suffering from depression are often withdrawn and disturbed 36. Anxiety can also lead to distorted memory. Distorted memory can confuse individuals to the point where they are unsure what is real and what their brain has conjured 37.

Head trauma can also lead to amnesia if exposed to repeated head injuries 38. In younger people, memory loss is often associated with repeated trauma to the brain (i.e., concussions) because of physical activities (i.e., sports). Honig et al. (2021) found that repetitive concussive and sub-concussive trauma can lead to long-term processes of neurodegeneration and memory decline 39. The study also found that repeated concussive and sub-concussive head trauma can lead to a neuronal loss on the dentate gyrus and CA1—a subfield of the hippocampus. In addition, the repeatedly concussive mice in the study showed vascular abnormalities in their dorsal hippocampi. Each of the aforementioned forms of memory loss is associated with the hippocampus and other structures of memory, such as olfactory and gustatory memory.

The olfactory system (sense of smell) has a multitude of functions in physiological regulation, emotional responses (i.e., anxiety, fear, pleasure), reproductive functions (i.e., sexual and maternal behaviors), and social behaviors (i.e., recognition of conspecifics, family, clan, or outsiders) 40. Interestingly, the olfactory system has its own distinct type of memory known as olfactory memory. An example of olfactory memory in action is when an individual smells something familiar, which reminds them of a specific memory. Semantic memory within the olfactory system refers to an individual’s knowledge or experience with a particular odorant 41. Odor identification and odor recognition describe odor memory 42. For instance, olfactory memory is subjected to familiarity (e.g., This smell is familiar) or hedonic qualities (e.g., This smell is fantastic) 43. Episodic memory in the olfactory system occurs when an individual is exposed to various odors and asked to recognize the odors at a later time 44. Classical conditioning can play a role in the olfactory system by pairing an unconditioned stimulus (a specific smell) with a conditioned stimulus (a particular sound) to produce a conditioned response. The conditioned response is that whenever the sound is heard, and the scent is smelled, this could trigger a reaction like hunger. Bahuleyan & Singh (2012) suggests that how smells are perceived, stored in memory, and recalled years later, has not been fully understood 45. Long-term memory of the olfactory system requires the release of glutamate and norepinephrine—two neurotransmitters that send messages in the brain and can be linked to memory loss. Why there is, a loss of olfactory memory in the brain is unknown at this time. There is limited research on the correlation between the hippocampus and the olfactory system. Future studies should look into how these parts of the brain are connected regarding memory. It can be suggested that memory loss or any neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s, cause neurons to diminish, become plaques, and decrease brain size—leading to a decline in neuronal connection. The decline in the neuronal connection may explain why the olfactory system is affected by memory loss since the hippocampus is not processing the information necessary for smell and memory.

For humans and other large land organisms, the gustatory system (sense of taste) records sensations that begin with stimulation from food or other substances 46. Humans most commonly recognize four preferences through the tongue’s taste buds (Figure 3): salty, bitter, sweet, and sour 47. Usually, the sweetness comes from sugars, saltiness from the table and mineral salts, bitterness from various factors, and sourness from acids 48. As seen in Figure 1, the gustatory system has direct projections to the amygdala, one of the essential structures for memory 49. Zald et al. (1998) found that exposure to an aversive gustatory stimulus activates the limbic system structures (amygdala, cingulate gyrus, hippocampus) 50. Therefore, lesioning in any of the limbic structures could lead to the inability to recognize the taste of foods. The neural processing of regulating the detection of flavors and initiation of automatic feeding is understood better than the mechanisms of taste memory 51. Resembling olfactory memory, there is currently limited research on how the gustatory system is directly related to memory or memory loss.

References

- Klein, S. B. (2015). What memory is. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 6(1), 1-38. ↵

- Thieman, T. J., & Mrazik, M. (2023). Memory storage. Salem Press Encyclopedia of Health. ↵

- Bird, C. M., & Burgess, N. (2008). The hippocampus and memory: insights from spatial processing. Nature reviews neuroscience, 9(3), 182-194. ↵

- Phillips, L. U., M. (2020). Flashbulb memory. Salem Press Encyclopedia. ↵

- Squire, L. R. (1986). Mechanisms of memory. Science, 232(4758), 1612-1619. Laakso, M. P., Frisoni, G. B., Könönen, M., Mikkonen, M., Beltramello, A., Geroldi, C., … & Aronen, H. J. (2000). Hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a morphometric MRI study. Biological psychiatry, 47(12), 1056-1063. ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Purves, D., et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Edition, Sinauer Associates, New York. ↵

- Purves, D., et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Edition, Sinauer Associates, New York. ↵

- Purves, D., et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Edition, Sinauer Associates, New York. ↵

- Purves, D., et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Edition, Sinauer Associates, New York. ↵

- Purves, D., et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Edition, Sinauer Associates, New York. ↵

- Squire, L. R. (1986). Mechanisms of memory. Science, 232(4758), 1612-1619. Laakso, M. P., Frisoni, G. B., Könönen, M., Mikkonen, M., Beltramello, A., Geroldi, C., … & Aronen, H. J. (2000). Hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a morphometric MRI study. Biological psychiatry, 47(12), 1056-1063. ↵

- Thieman, T. J., & Mrazik, M. (2023). Memory storage. Salem Press Encyclopedia of Health. ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Laakso, M. P., Lehtovirta, M., Partanen, K., Riekkinen Sr, P. J., & Soininen, H. (2000). Hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease: a 3-year follow-up MRI study. Biological psychiatry, 47(6), 557-561. ↵

- Laakso, M. P., Lehtovirta, M., Partanen, K., Riekkinen Sr, P. J., & Soininen, H. (2000). Hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease: a 3-year follow-up MRI study. Biological psychiatry, 47(6), 557-561. ↵

- Your brain and alzheimer’s. Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research Foundation. (2023, March 17). Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://www.alzinfo.org/brain/ ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Hartmann, P. M., MD. (2022). Anxiety. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Piotrowski, N, A., PhD, Cancellaro, and L. A., MD, & Hamdy, R. C., MD. (2022). Memory loss. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition). ↵

- Honig, M. G., Dorian, C. C., Worthen, J. D., Micetich, A. C., Mulder, I. A., Sanchez, K. B., … & Reiner, A. (2021). Progressive long‐term spatial memory loss following repeat concussive and subconcussive brain injury in mice, associated with dorsal hippocampal neuron loss, microglial phenotype shift, and vascular abnormalities. European Journal of Neuroscience, 54(5), 5844-5879. ↵

- Lledo, P. M., Gheusi, G., & Vincent, J. D. (2005). Information processing in the mammalian olfactory system. Physiological reviews, 85(1), 281-317. ↵

- Larsson, M. (1997). Semantic factors in episodic recognition of common odors in early and late adulthood: a review. Chemical Senses, 22(6), 623-633. ↵

- Larsson, M. (1997). Semantic factors in episodic recognition of common odors in early and late adulthood: a review. Chemical Senses, 22(6), 623-633. ↵

- Larsson, M. (1997). Semantic factors in episodic recognition of common odors in early and late adulthood: a review. Chemical Senses, 22(6), 623-633. ↵

- Larsson, M. (1997). Semantic factors in episodic recognition of common odors in early and late adulthood: a review. Chemical Senses, 22(6), 623-633. ↵

- Bahuleyan, B., & Singh, S. (2012). Olfactory memory impairment in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR, 6(8), 1437. ↵

- Fields, M. C., MD. (2022). Taste. Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science. ↵

- Fields, M. C., MD. (2022). Taste. Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science. ↵

- Fields, M. C., MD. (2022). Taste. Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science. ↵

- Zald, D. H., Lee, J. T., Fluegel, K. W., & Pardo, J. V. (1998). Aversive gustatory stimulation activates limbic circuits in humans. Brain: a journal of neurology, 121(6), 1143-1154. ↵

- Zald, D. H., Lee, J. T., Fluegel, K. W., & Pardo, J. V. (1998). Aversive gustatory stimulation activates limbic circuits in humans. Brain: a journal of neurology, 121(6), 1143-1154. ↵

- Masek, P., & Keene, A. C. (2016). Gustatory processing and taste memory in Drosophila. Journal of neurogenetics, 30(2), 112-121. ↵

- Fields, M. C., MD. (2022). Taste. Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science. ↵

12 comments

Mia Garza

This is a well-written article that emphasizes the significance of cherishing our memories. I have never thought much about the science behind memories and this article does a great job of explaining it in a way that is easy to understand. Not only does it explain memories but it goes into what affects our memories and the types of neurological problems.

Maximillian Morise

Once again, neuroscience proves to be one of the most fascinating fields of study and you have shown with your article just how deep it can go. The explanations on the various types of brain systems and how they work are what I found most intriguing. Congratulations on your article and nomination!

Jared Sherer

Very well written article. I think you did a great job with detail and providing a lot of important information. I think it is interesting that there are two types of memory loss. Partial and complete, which I never knew about. I learned that damage to either of the hippocampus regions could cause new memories to not form. I was interested in your article and I thought it was enjoyable to read as well. Awesome job on this work!

Isabel Soto

Congratulations on your nomination and for writing a great article! Memories are important to have because they can help shape you as a person. The ability to loose your memory is scary just because of how hard it is to treat. The author did a great job on making the article very informative and giving little important details. Overall it was a great read over a topic people should learn more about.

Andrea Tapia

Hi Joel, congratulations on getting your article published! When I had such first saw your title it made me curious what about memories where you going to talk about. After reading it I loved everything it said and the information behind it. How you talked about the different types of the brain and how they work. And really how memories work us not really knowing how we can remember things that had happened years ago. I was aware that depression had such an effect on memory loss because it’s devastating to know young kids now can’t remember a lot. It is such a hard topic to speak about, but you did amazing in explaining it!

Nnamdi Onwuzurike

Congratulations on your nomination! “Memories” is a beautifully written and thought-provoking piece that highlights the importance of cherishing our memories and the people and moments that make them. The article’s evocative imagery and poignant insights remind us of the power of our past experiences in shaping our present and future. The author’s candid reflection on the bittersweet nature of memories underscores the complexity and depth of human emotions, making this piece a truly captivating read.

Madison Magaro

Congratulations on your nomination and for writing a great article! Memories are important to have because they can help shape you as a person. The ability to loose your memory is scary just because of how hard it is to treat. The author did a great job on making the article very informative and giving little important details. Overall it was a great read over a topic people should learn more about.

Matthew Holland

Memory and the ability to lose it has always been a very interesting field of study for me and I am always impressed to read about such interesting findings when it relates to that field. I hope that this author write more about this subject as it was a very interesting read and it provided a lot of very good information on a topic not covered by many people.

Jonathan Flores

This topic hits especially close to home as I know many people that have suffered through dementia and other neurological problems that have caused memory loss. I think your article did a great job at explaining exactly what these things do scientifically and I appreciate that. Unfortunately, these neurological problems are tough to treat but I’m glad that you tackled such a heavy topic. This was a very well done article and Congratulations on being published!

Alanna Hernandez

Memories are the one thing I thinkn we take for granted the most from our brains and the thought of Alzheimer’s and dementia fears many people. but it’s not just those things that can make people lose their memory, like you had mentioned about depression, or trauma. While ell, these are heavy topics we continue to search for treatment through important research that needs to be written about more.

Hailey Koch

Great job on your article, you did a great job. I love the topic you choose because I was able to learn lots of new things that I didn’t know before about memory. Before I thought memories were just memories, that they were simple things you remembered from things that occurred from past time. It’s incredible to learn that “Depression can cause memory impairment” I was unaware that one that may be going through depression may have trouble remembering certain things. I thought this only happened to older people who may be going through something because of age.