April 7, 2024

Modern Changelings: Understanding How Our Depictions of Autism have Changed Over Time

An Autism Narrative

It was around 10:30 AM, and Alex1 found himself walking to an unfamiliar office at school. This was not where he was supposed to be at this time, and this bothered him, but not as much as why he was there. He returned from spring break vacation to find a note on his door requiring that he meet with campus security. This would be the second time this happened, and Alex was worried about what could have required it this time. What would his parents think? He climbed up the stairs to the office and opened the door. He told the receptionist he was there for a meeting and was led into a backroom. The room was bare, save for a table and three chairs. In one chair sat an unfamiliar woman in business attire. In the other chair was a slightly more familiar face. He had met that face when he was called in the first time because a student had seen him looking up guns and was scared. Before the meeting started, he asked if he could put his mom on the phone, which he could do. He sat the phone in the center of the table and put it on speaker. The two other participants introduced themselves to the mother on the phone. The campus officer then read Alex’s Miranda Rights, which the officer reassured was just procedure, and then got into the real purpose of the meeting. The officer explained that Alex had made a disturbing joke to a classmate in Spanish class, after said classmate lost a card game. The joke in question was “Now you get executed by firing squad.” Alex was confused. He remembered making that joke but hadn’t even thought about it after he said it. What was the big deal? It turns out, that the people who were at that table reported him for it, a total of five people came forward, one of them was a student who had reported him previously. Alex was quick to explain what he thought was obvious, it was just a joke. Alex’s mom was quick to ask more questions to the two attendants. It turns out the joke was not the only thing reported about Alex. There was also his habit of scribbling random drawings on his paper which explained the rules of the game, and his habit of going to the restroom at near specific times. Alex almost wanted to laugh. Seriously? He doodled a picture of a monstrous snake out of boredom, and went to the bathroom, and they feared him for it? The conversation took a turn for the better as solutions were worked out and information came to light. Alex was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome (later folded into high functioning autism) when he was five years old, and his strange behaviors have previously gotten him into conversations with authority figures. From joking about writing on paper in his own blood, to making a joke about overthrowing the prom king and queen in a revolution, Alex had stood out. This was no different to Alex, another “nothing burger” of a situation. It was determined that Alex could go back to class, and plans were made to inform the repeat reporter of Alex’s condition. Since then, Alex gave barely any thought about the situation, although he did wonder why he was singled out. This sort of differential treatment is a common experience among those with autism spectrum disorder. In fact, Alex arguably got lucky. He was born in the 21st century, where Autistic people are not considered changelings who replaced a “normal” child, but as human beings. He was never subjected to inhumane treatments like electroshock therapy, nor was he ever put into a near death situation via outdated therapeutic techniques. He is considered white, and therefore less likely to be harassed by police which, compounded with his condition, could have resulted in his arrest or worse. He was born with well-off parents who cared enough about him as a person to help him succeed in a world which considered people like him as a burden or a potential risk. That cannot be said for a lot of people with autism spectrum disorder, high functioning or not. This sort of mistreatment dates back centuries and is as much a product of the media as it is a product of outdated medical theories. It is a reality that continues in some form today. What is different about today, at least from a Western perspective, is Autistic people are fighting back, and having their voices heard. Over the course of the 20th to 21st century, what autism was classified as changed over time to become more complex, and as such more people were diagnosed with the condition, therefore becoming self-advocates capable of inspiring real change.

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, is a tool used by psychologists to diagnose mental conditions. According to the fifth edition of the publication autism spectrum disorder is characterized by two primary symptoms. Firstly, Persistent deficits in social communication. This is usually in the form of deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, deficits in nonverbal communication, or deficits in developing relationships. For example, an autistic child might not engage in imaginative play as much as his peers, or an autistic adult might not look in someone’s eyes while talking to them. The second symptom is repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. This can manifest in repetitive motor movements, insistence on sameness and strict adherence to routines, highly restricted interests, or an over or under reaction to physical stimuli. For example, an autistic person might be interested in medieval Europe, and as such only want to talk about medieval Europe, or an autistic person might go to dinner at a very specific time.2 However, “If you have met one person with autism, you have met one person with autism,” as explained by Dr. Stephen Shore, an Autistic educator. It is a quote that has gained traction within the Autism community, as it highlights the different ways autism can manifest in a person.3 This is why autism is considered a spectrum disorder, with a wide range of symptoms and complications. In simple terms autism occupies three levels in the DSM-5, categorized by how much assistance an autistic person needs. At level three, a person requires a lot of support, at level 2 a person requires substantial support but much less than level three, and at level one, a person only requires some support.4 Occasionally the term autism may be capitalized or not, it really depends on the context. Non-capitalized autism is used to refer to people with a medical diagnosis of autism but not identify culturally with autism. Whereas Autism refers to people who identify with Autistic culture but may or may not have a diagnosis.5

Early Autism History

While the modern, clinical understanding of autism dates back to the early 20th Century, people with autism have existed for as long as humanity has been around. In Europe, people with autism were considered much in the same way as people with other disabilities, in that they were considered changelings. Changelings, in this instance means a fairy child that replaced a couples “real child.” Rhyming, and the repetitive speech patterns associated with conditions like autism and hypercalcemia were interpreted as “Changeling Poetry.”6

The first clinical description of autism begins with the 1908 description of Heller’s Disease, where at three or four years of age, a patient regressed in language skills. While the individuals studied might have had autism, the first true use of the term was in 1911. German Psychiatrist Eugene Bluer used the term autism to refer to the replacement of an unsatisfactory reality with an individual’s inner world. 7 In this case, autism was considered a most severe form of schizophrenia, an idea which stuck through the 1960s.8 One of the most comprehensive of these was from Russian psychiatrist Ssucharewa. While Ssucharewa wrote her paper on “Schizoid Personalities”, her case histories proved similar to the case histories of modern-day high functioning autism. Such elements include patients who were easily frightened, had repetitive language, restless sleep, had exceptional musical talent, or had awkward movements. 9 However, the more widely publicized research was Kanner’s 1943 paper, “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact,” which noted a difference between patients with schizophrenia and patients with what would become autism. In the latter case, the condition manifested much earlier and yet still enabled average or even above average intelligence in certain areas.10 It was through the process of writing this paper, that Kanner diagnosed the first person with autism, Donald Triplett. Despite Kanner’s grim prognosis of Triplett, he would go on to earn a college degree in French and work as a bank teller in the bank founded by his parents. 11 Through the 1960s and 1970s, treatments for autism emerged from the belief of the condition as a disease, an illness to be eradicated. This view justified experimentation with LSD, electric shocks, isolation, and pain-inducing behavior change techniques. 12 This began to change in the 1960s. Firstly, with Rimland’s Diagnostic Checklist for Behavior-Disturbed Children. The 1964 checklist placed emphasis on the assessment of the core symptoms of autism and while still building off the conception of autism as childhood schizophrenia, the heading of autism symptoms as parts to be assessed continues to the modern era. Just two years later, in 1966, Ruttenberg built off the Diagnostic Checklist with the introduction of The Behavior Rating Instrument for Autistic and Atypical Children. This marked the first attempt to diagnose autism based on clinical observations, rather than just using parent reports. 13 The information gathered from this development led autism to be considered more of its own unique condition and not just the earliest manifestations of Schizophrenia. As a result, Ruter in 1978 proposed a new definition of autism, one that focused on delayed or otherwise unordinary social behavior and abilities, alongside restrictive interests, which proved highly influential in 1980 DSM-III, which included autism in a new class of condition, the pervasive developmental disorder.

Autism enters the Mainstream

Between DSM-III and DSM-IV, DSM-III-R was released in 1987 as a revision of the previous DSM-III. The 1987 revision upgraded how autism was described. Firstly, it changed the name from infantile autism to autistic disorder. This change might seem minor, but it emphasizes autism as a lifelong condition, not just one relegated to children. DSM-III-R also developed a set of 16 diagnostic conditions for autism, that were divided into the three main conditions of Autism: problems with communication, restricted interests, and impairments in social reciprocation. While the understanding of Autism was still limited in DSM-III and its revision, the understanding of autism as a separate condition resulted in an explosion of interest in Autism. 14 The late 1980s is when autism was first introduced in mainstream media as autism, most famously in the form of the movie Rain man (1987). Despite the film’s title being a pun on the name Raymond, the autistic character is less of a character and more of a MacGuffin. The film instead focuses on Tom Cruise’s character, a selfish salesman in financial trouble, who learns that he has an autistic older brother committed to an institution by his parents. When he finds out that Raymond (or specifically his institution) was granted the inheritance by their late father, Tom Cruise’s character tries to gain custody over his older brother to access the inheritance. Initially annoyed with Raymond, when he finds out that he is a savant with numbers, he uses him to win money at the casino. In the end the two bond. 15 While the film is dated in its depiction of autism, it was an important first step in getting the word “autism” out into general use. After all, it would not be until 1994 that Raymond would have the chance to be diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome via the DSM-IV. 16 Unfortunately, it also set in stone a formula for how Autistic characters were represented, a formula that would not see any change for years.

According to Anthony D. Baker in “Recognizing Jake: Contending with Formulaic and Spectacularized Representations of Autism in Film,” the early films that followed Rainman with Autistic characters tended to follow a formula. Firstly, the neurotypical main character is introduced. In Rain Man‘s case, this main character is the aforementioned selfish businessman played by Tom Cruise. In Mercury Rising (1998) the neurotypical character is a renegade FBI agent played by Bruce Willis. Then the autistic character is introduced, and endowed with some special savant skill, usually with numbers. In Mercury Rising, the autistic character is nine-year-old Simon, who requires strict routines in his life and avoids direct eye contact. His savant skill is what sets the plot in motion, as he is able to crack a super secret government code just by looking at it, and thus is made a target by the government. In the movie Cube (1997), where a group of prisoners must escape a high-tech, mysterious, and dangerous structure, the autistic character is Kazan, who rocks back and forth. While in such a situation, Kazan would be left behind to die, it is his complex calculating abilities which enables him to calculate the numerical patterns of the numbers along the cube’s hatches. Sometimes, the power granted to the autistic character is of a supernatural variety, like how Cody in the movie Bless the Child (2000) is able to heal people with just her touch. The autistic characters vulnerability is then highlighted, usually by showcasing the Autistic characters vulnerability, via a reliance on caregivers such as institutions or parents. These safeguards are then removed, and the Autistic character is put in a dangerous situation. In Mercury Rising, Simon’s ability to crack the government code makes him a target of the NSA, who murders his parents and continually try to murder him. In Bless the Child, Cody’s birth mom joins a Satanic cult, and seeks to regain custody over Cody to use her powers of healing to further their goals. The autistic character being in danger gives the perfect opportunity for the neurotypical protagonist to swoop in and save the day, with the protagonist having grown as a character and showcasing themselves capable caregivers. In Mercury Rising, this manifests in Bruce Willis’s character hugging Simon after the adventure ends, in Bless the Child, Cody returns to living with her aunt, and in Cube, Kazan is the only character able to escape the cube, thanks to another inmate holding a dangerous inmate back. The problem with these stereotypical plots, beyond being generic, is what they teach the audience. While rates of autism diagnosis are increasing, film remains the primary way of exposure for the general public to Autism. Which in turn influences how the general public thinks of Autism, and by extension Autistic people.17 For example, the prevalence of savants makes audiences think that being Autistic must mean being a savant. In actuality, being a savant is not common among autistic people. This discrepancy between how many autistic people are savants, and how many autistic characters are savants can lead to frustration or disappointment among neurotypicals when an autistic person does not turn out to be a savant.18 What’s more, the fact that these savant characters are not given any kind of character growth implies that autistic people are incapable of change. That they are uncaring robotic supercomputers. On a more troubling result, these films carry an implicit message. That an autistic person only has worth if they have some freak special skill. If applied to real life, this would make the majority of autistic people “worthless.” 19

Over time, these portrayals have only slightly improved. Autistic people are still overwhelmingly represented by white males in tv and movies in the west. Newspapers still mainly focus on autistic children, and a third still showcase signs of negative stigmatization through viewing autism as a disease. There has been some positive growth in terms of video game and social media representation, but, while these are still important media sources, they haven’t had the authorization through years of existence. Fiction literature has seen some improvements, but 81% of Autistic characters in literature are children, which contributes to the infantilization of Autistic people. 20 According to “Still Infantilizing Autism? an update and extension of Stevenson et al. (2011),” the infantilization of Autistic people is done through an overrepresentation and overfocus on Autistic children. As a 2022 update to a 2011 study, the article utilized the same techniques used by Stevenson highlighting the infantilization in not just movies or TV, but in newspapers, books, and charity ads. Of the Charity websites, five of the eight websites had language reflecting both autistic adults and children , up from three in 2011. However, four of the six websites that had photos used only autistic children. The usage of children in these cases reflects a purposeful marketing technique, as children generate more sympathy than adults. Of the 124 movies and television shows studied, 58% of the autistic characters were children, a decrease from 68% in 2011. For fictional books, 75%-85% of the autistic characters portrayed were children. For news media, 59% of the articles featured Autistic children, down from 79% in 2011. However, the study noted that of the news stories that featured autistic adults, a third had their parents mentioned thereby still infantilizing the autistic adults. 21 One of the biggest contributors to autism stigma, however, does not come from TV or movies, but from a charity organization.

One of the largest autism charity groups, Autism Speaks, has had a very troubled past. The story of Autism Speaks began in 2004, when a boy named Christian was diagnosed with autism. Inspired by this diagnosis, Christian’s grandparents Bob and Suzanne Wright established the organization in 2005. Autism advocacy was far from a new idea at the time. What made Autism Speaks different was who ran it, more specifically, Bob Wright. Bob Wright was the CEO and Chair of NBC Universal, and as such had contacts with members of the Media elite, and access to resources. The organization was further advanced by their first donation from their friend Bernie Marcus. How much was this donation? Twenty-five million dollars. This donation, and the Wright’s already existent resources, enabled Autism Speaks to absorb related organizations who had less funding. By 2014, Autism Speaks had raised almost $60 million dollars.22 For much of its history, the organization focused less on helping autistic people and more on preventing the existence of more of them. Their focus was on the goal on finding a cure for Autism, as well as funding research into the genetic causes of Autism, rather than focusing on helping autistic people with legitimate common medical problems, such as gastrointestinal complications.23 In 2014, only 4% of Autism Speaks budget was invested in directly beneficial services for autistic people or their families. Its name was also extremely ironic, given how, for most of its history, Autism Speaks had little actual input from Autistic people. Only in 2015 were two Autistic individuals added to the Board of Directors.24 Before then, the most prominent Autistic voice in Autism Speaks, John Elder Robison, resigned from the organization on November 13, 2013. This was because Autism Speaks had announced an Autism summit to be held in Washington D.C, without a single autistic person scheduled for attendance. To make matters worse, in early November of 2013, Suzanne Wright posted an article suggesting that millions of autistic people were lost, taken from their families by Autism. Not only is this a call back to early changeling myths about Autism, but it also reflects a lack of change in the Wrights in their almost decade long “advocacy” effort.25

Most damning for the organization, however, has been its fundraising attempts. In 2009, it released the film I Am Autism, created by award winning director Alfonso Cuaron, with a script written by Billy Mann, who was part of the Autism Speaks board of directors.26 The video starts with a threatening voice over, the personification of Autism in the organization’s mind. This voice over is produced alongside screams and cries of children, over perfectly healthy children, and one adult. The voice claims that it works faster than actually lethal diseases, such as AIDs, cancer and diabetes, and that it will bring ruin to any marriage, bank account, or community. This threatening tone is dropped for an upbeat tone in which parents, teachers, brothers, sisters, and everyone in an autistic person’s life (excluding the autistic person themselves of course) claims that they will fight back with genetic resources and hope, as well as more unconventional and ineffective means, such as voodoo, prayer, or herbs.27 While I Am Autism is ostensibly a piece of cheap scare marketing, it is not the worse film Autism Speaks produced. Less than two years after its founding Autism Speaks released the short film Autism Every Day. Beyond its white washing of people with autism by showcasing exclusively white autistic children, the film dehumanized the autistic children by almost always showcasing them as having a meltdown. 28 On top of which, the parents were told not to bring in therapists, do their children’s hair, or vacuum their house during the process of filming in favor of securing a more “authentic” look into life with an autistic relative. 29 While these can loosely be excused as incredibly unethical attempts at fundraising help for the children, what cannot be excused is the statements of one Alison Tepper Singer, a former executive for Autism Speaks. In response to inadequate classrooms for her autistic child, she considered putting her autistic offspring in her car and then driving off a bridge. The only reason this murder-suicide was not committed was because of Singer’s neurotypical child. All this was said, while her Autistic daughter was in the same room as her.30 At best, including such a statement in a fundraising film is ludicrously irresponsible, and extremely devoid of ethics or a respect for human life. At worst, it treats Autistic people as less worthy of life than neurotypical people and justifies their abuse. To Autism Speaks credit, their website suggests they are trying to change. After all, Bob Wright resigned from his position a short period after the passing of his wife in 2016. 31 The FAQ section of the website acknowledges their removal of the film, I Am Autism and dropping the phrase “cure” from their mission statement. It even apologizes for its “missing the mark” in representing autism. 32 It will, however, take more than corporate speak to fix a decade and a half of ablest rhetoric. It will be Autism Speaks future actions, not its current words, that will tell if the organization truly wishes to redeem itself.

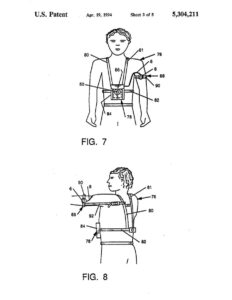

In the meantime, the rhetoric espoused by Autism Speaks in which autistic people are tragedies is nothing new. This climate of fear and dread around autism has resulted in the pursuit of “cures” for the condition. Autism cures occupy a spectrum of ideas, as suggested by the Autism Speaks film, I Am Autism. From dietary restrictions, vitamin supplements, and chemical injections, 33 to vaccine refusal, buying “natural” products, and traditional Chinese medicine, there was no product that desperate parents would try to “get their children back”. Those who promoted these treatments also promoted “causes” of autism, such as harmful chemicals in modern American manufactured products, Wi-Fi signals, or vaccines.34 The therapies to “fix” autism cost parents thousands of dollars and worse, harmed the autistic people they were practiced on. 35 For example, in 2005 Abubakar Nadama, a five-year-old autistic boy, was taken to Dr. Roy Eugene Kerry at the Advanced Integrative Medicine Center in Pennsylvania by his mother. There, Abubakar was injected with a chelate. Chelation therapy is a technique used to remove heavy metals such as lead, mercury or arsenic from the body by introducing chemicals that grab these metals in the bloodstream and enable their easy excretion. Dr. Kerry believed that since Abubakar’s autism was caused by heavy metals introduced from vaccines, that the chelation process would remove these chemicals from the blood and “save” Abubakar. What actually occurred, was tragic. Little less than an hour after Abubakar was injected, he died of a heart attack.36 In a much later occurrence, Misha Summers, who was diagnosed with autism at age 3, was subjected to numerous pseudo-medicines by his father John. These medicines contained bark, boldo leaf, water that would supposedly “remember” chemicals, ethanol alcohol, and numerous other ingredients. Alongside John’s refusal to vaccinate Misha with either a pneumonia vaccine or a chickenpox vaccine, the results were harmful. Misha suffered from red rashes, diarrhea, constipation, lethargy, and recurring fevers. Black rings formed under his eyes, his skin was pale, and he stopped gaining weight. Thankfully, after eighteen months, John came to his senses and stopped subjecting Misha to this treatment.37 It would not only be alternative medicine that would subject Autistic people to abuse, however. Just south of the historic city of Boston, there is a compound known as the Judge Rotenberg Center. Here, not only is there violence against autistic and other mentally divergent individuals, but also a dark intersection between the racist elements of the United States, and unregulated capitalist culture. The Judge Rotenberg Center, or JRC, was founded in 1971 and remains in operation as the only institute in the United States to still use electric shock therapy. 38 The center was founded by Matthew Israel, under the name of the Behavior Research Institute (BRI). Israel was inspired by the novel Walden Two, by B.F Skinner which described a utopian society that functioned on behavior modification techniques. 39 For the first two decades of its existence, the BRI didn’t use electric shocks.40 However, from the first few years of its operation, parents were rightfully concerned with the conditions their children were subjected to. Matthew Rossi, who had offered his home and summer camp to Israel on Prudence Island for the treatment of two adolescents, had entrusted his son, diagnosed with schizophrenia, to him. In a letter to Harvey Lapin on September 9th, 1976, in which he claimed that Dr. Matthew Israel was not the right person to be treating children, as evidenced by a four key incidents, such as a parent finding their fifteen year old daughter being held by their hair against a wall, use of a closet converted to a padded cell for people who did not conform, replacing staff who disagreed with his methods, and the death of a pigeon who was also subjected to behavior modification.41 The problems really became apparent with the use of electric shock devices. The BRI first utilized the Self Injurious Behavior Inhibiting System, or SIBIS. The SIBIS was designed by Mooza Grant with the goal of regulating self-injurious behavior. It was essentially a helmet hooked up to an electronic source that, whenever the helmet was struck, would shock the wearer’s limbs with a voltage of 85 volts.42 After using the device on 29 students, Israel would view this device as insufficient, and issue a request to the FDA for approval of a new device that would be three times more powerful. The FDA rejected, not due to the obvious moral problems, but because they feared that the electric shock wouldn’t be powerful enough to discourage unwanted behavior. As a result, Israel developed the Graduated Electronic Decelerator or GED, in 1992. The GED was a device that straps around the waist via a belt pack. The cord ran through a small hole in the back of the belt pack, under the student’s clothing.43

This would later be replaced by the GED-4, also developed by Israel, because the GED was still considered insufficient in strength. The GED-4, on the other hand, could deliver 60 volts and 15 milliamps in two second bursts. For reference, a taser only deploys an average current of 2 milliamps, over the course of nineteen short pulses. 44

This would later be replaced by the GED-4, also developed by Israel, because the GED was still considered insufficient in strength. The GED-4, on the other hand, could deliver 60 volts and 15 milliamps in two second bursts. For reference, a taser only deploys an average current of 2 milliamps, over the course of nineteen short pulses. 45 To further illustrate the point, a volt is around 1000 milliamps. So, 60 volts would be equivalent to around 60,000 milliamps. 46 For reference, at over 2000 milliamps, a person goes into cardiac arrest. 47 So the patients with this device on them were essentially walking around with the equivalent of a bear trap around their neck, ready to snap at any moment. While the BRI, later named the Judge Rotenberg Center, likely never used the GED-4 at its full power at once, the lowest shocks given were twice the tolerable pain threshold for most humans. The students at the BRI, and the later Judge Rotenberg Center were clearly abused using these kinds of outdated techniques. The JRC also used other methods that are deemed as forms of torture, as detailed by former JRC resident Jennifer Msumba, who had been a resident at the JRC for seven years. 48 In her letter to Nancy Weiss in December 2012, Msumba described searing pain in her lower left leg after being shocked there and losing all feeling in that region below the knee for a year. The shocks were painful enough that she would often have a limp for one or two days after getting shocked. She described being threatened and witnessing non-verbal students being scared into submission by feinting shocks, which the staff laughed about. The shocks were administered for “horrible” behaviors like waving your hand in front of your face for more than five seconds, uncontrollable verbal tics, or even just tensing your fingers or bodies. She describes one experience when she was suddenly woken up during the night via an electric shock (students had to wear the GEDs even while they slept) and when she cried out and asked why, she was simply shocked again. The reason for this? A piece of plastic was found in her self-care box, probably something that broke off a container, and the staff considered this a weapon. Sometimes, the staff would restrain residents on a restraint board and shock them multiple times for one behavior, all in view of other residents. This is not even accounting for the humiliation, such as Msumba being forced to wear a diaper despite having never needed a diaper before since she was a baby.49

The center was able to get away with these behaviors because of powerful allies. After all, the reason behind the name change to the Judge Rotenberg center in 1994 was to honor the late probate court judge who was responsible for supporting the use of aversive therapies during the certification process, and who supported a lawsuit against the center’s critics.50

It has seen support from the federal government, state legislatures, state agencies, courts, and even the aforementioned organization, Autism Speaks. 51 The FDA only issued a ban on electrical stimulation devices on March 4th, 2020, and that decision was stayed due to request from the JRC, and the Covid-19 pandemic. That decision was further overturned on July 6 of 2021 by the U.S Court of Appeals in a two to one decision. 52

Most concerning of all, is how the ableism of the Judge Rotenberg Center intersects with racist elements of American society. Over 85 percent of the JRC’s current population are Black or Latine.53 Minorities are referred to the center from local education agencies, adult disability service systems, and the juvenile criminal legal system.54

In fact, the few people punished for the physical abuse committed, tended to be low-paid line workers who were largely immigrants of color, whereas the mostly white administration sees little consequence. The Judge Rotenberg Center is just the place where the most extreme form of violence occurs. Similar institutions permit mistreatment of students by abuse, torture, or even murder. According to activist Mel Baggs, an institution can be as small as a single person, so long as the agency of an individual is placed in the hands of another.55

Raising an autistic child, or any neurodivergent child, can be taxing on parents. Parents of autistic children are more likely to face serious psychological problems then parents of other developmentally disabled children, due to the vast spectrum autism occupies and the lack of a cohesive treatment that works on every autistic person.56 There is also a stigma that comes with being a parent with an autistic child, such as feelings of embarrassment when their child acts in an inappropriate way or being asked to not bring their autistic children to family gatherings.57 But does the autistic person deserve to die from this? Do they deserve to be subjected to torturous therapies, dangerous pseudo medicines, physical abuse, or humiliation? Is having a child with Autism worse than having a child die from polio, measles, or COVID? Are the many Autistic authors, activists, parents, scientists, or people cited thus far just burdens that can barely be considered humans? Do we define a person’s humanity on a ratio of annoyance to usefulness? The answer is clearly no, and Autistic voices clearly state so.

Neurodiversity

Over the course of the 21st century, more and more Autistic voices have spoken up, forming the neurodiversity movement. According to Nancy Bagatell in the article “From Cure to Community: Transforming Notions of Autism,” the emergence of this movement can be attributed to three key developments: The widening of autism diagnosis to include Asperger’s Syndrome and High Functioning Autism, the emergence of the disability rights movement and the popularity of computer technology in the form of the world wide web. The expansion of Autism diagnosis caused more people to get diagnosed. Those people who now found themselves diagnosed came from a wide range of life paths and had varying levels of support needs. 58 As such, some could talk for themselves and explain their perspectives as Autistic people. The development of the self-advocacy movement can be traced to Sweden in the late 1960s. The director of the Swedish Association for Persons with Mental Retardation, Dr. Bengt Nirje, established a club for neurodivergent (then labeled people with mental retardation) and neurotypical people to meet. The people who met via the club would organize a later meeting, attend it, and then return to the club and explain their experiences. The goal of the club was to provide neurodivergent people with as close to a “normal” social life as possible, and to encourage neurodivergent people to define their own role in society. Dr. Nirje mentioned that there would be risk, and that was the point. Neurodivergent people should be allowed to fail, because that is what being human is. 59 The idea of self-advocacy spread to the United States in the 1970s, with the establishment of People First in 1974. By 1994, there were 505 similar self-advocacy organizations in the United States, from the 14 identified in 1974.60

Autistic people also began to write about their experience, most notably in the books Emergence: Labeled Autistic by Temple Grandin in 1986, and Nobody, Nowhere, by Donna Williams in 1991. While the two books were revolutionary in promoting the radical notion that autistic people could actually think, speak, and write for themselves, they were still written for neurotypical people, and in the climate of autism as a disease. This meant that both books had to conform to that notion. In the case of Emergence, the book begins with an introduction from scientist Bernard Rimland, both reassuring skeptics that she was “actually autistic” and to celebrate Grandin’s “recovery.” The book continues this rhetoric of autism as a tragedy, with her description of her “regression into autism” at six months being informed by her mother’s perspective. There was also an incorrect contextualization of an incident where Grandin “almost killed her mother and younger sister.” The incident in question? Well, while her mother was driving, Grandin threw an uncomfortable hat out the window and her mother lost control of the car in response. The latter book, Nobody, Nowhere, was a bit more positive, with Williams admitting some enjoyment in solitude, and emphasizing the importance of some of her stims, but the book still fell back into the paradigm of autism as a tragedy. The book does criticize how William’s family treated her, with her personhood and agency constantly reduced to her being either a “retard” or a “nut,” but William’s also assumes some level of guilt for their abuse, as the abuse was “understandable” even if it was unacceptable. The real paradigm shift was in “Don’t Mourn for Us” by Jim Sinclair. The article challenged the idea of autism as a tragedy, and instead focused on the societal factors that caused autistic people to be labeled as burdens. Sinclair claimed that the grief from a parent learning that they have an autistic child was not because the child was autistic, but because the parent consumed the cultural assumption that the children of parents are supposed to be “normal.” Xe 61 also, combated the idea of autistic people being in their own unreachable world, by imploring parents not to try to communicate with their child through the parent’s preferences and perspective, but instead to communicate with the child from the child’s perspective and preference. Sinclair’s radical stance would cost xim professional opportunities, and even made xim homeless for a time. However, xyr ideas of autism as something to be understood, rather than a tragedy, encouraged the formation of the first self-advocacy groups for Autistic people. 62

The first self-advocacy group specifically for Autistic people began, ironically enough, through a meeting at an organization run by Neurotypical people. While the majority of the verbal Autistic people who founded Autism Network International met via the pen-pal lists, a few did meet in person via the autism conferences the organization put on. Despite the name autism conference, the environment was not comfortable for Autistic people. Between the crowds, lots of noise, fluorescent lights, and perhaps worst of all, the constant moaning of presenters or attendants claiming that autistic people were defective humans who bring only grief to their families, it was decided that it would be better for Autistic people to have their own organization. As such the Autism Network International was established in the early 1990s. Initially, this organization relied on letters and pen pal lists in order to communicate, but it was the introduction of the internet that allowed for the organization to extend its reach. 63 Communication via the internet enabled autistic people to communicate free from physical restraints and boundaries, such as extensive external stimuli or “word freeze.” It is this combination of factors that has allowed the development of Autistic communities. 64 Social media has also proven to be a way of organizing. Most social media sites do not require a person to go through a publication process, editorial review, or extensive background checks to post a person’s thoughts. While this can be harmful in allowing the spread of fake news, it also provides a way for anyone to have their voices heard, or in this case read, by anyone else in the world. Autistic individuals have taken advantage of this, and begun fighting back against stereotypes and misrepresentation, creating more positive sources of Autism information. 65 As mentioned with ANI, the internet has allowed movements to spring up and advocate for change. For example, Meg Evan’s Star Trek Fanfiction website Ventura33, became a gathering point for autism activism when a genocide countdown was added in 2005. The genocide countdown was established in response to the growing mainstream optimism in finding the Autism genome and in being able to screen for prenatal tests within ten years. This could mean that a mass eugenics campaign could ensue, in which the world was rid of Autism through aborting fetuses with the signs of Autism, especially since the prevailing views of autism at the time were overwhelmingly negative. The countdown clock was taken down in July 2011, as Evans felt that the various autism advocacy groups had changed enough of the cultural understanding of autism so that pre-natal scanning for eugenics purposes wouldn’t be an issue. 66

That’s not to say that there has not been push back. According to Jim Sinclair, negative reactions to the self-advocacy of not just Autistic people, but to self-advocacy efforts by disabled people in general came in three forms. Firstly, the denial that the person mounting challenges to the status quo are really members of that group. In Sinclair’s case, this came from the Autistic Society of America in 1992. In response to xyr attempts to organize due to the failures of ASA to meet the promises to promote autistic self-advocacy, some of the board members began rumors that Jim was not really autistic. This was in spite of the fact that xyr records were reviewed by two psychologists of the ASA advisory board, both of whom confirmed that xe was autistic. A second tactic was to claim that the self-advocators condition was somehow different, that xyr experience or wants could not be applied to everyone with that condition. Such was the case with Michael Kennedy, who despite irrefutable evidence that he did in fact have Cerebral Palsy, critics claimed that he was higher functioning than the rest. This not only serves to put down those with more severe manifestations of a condition, but it also divides a self-advocacy community between those who have a say, and thus should be ignored because they don’t represent the latter group who is more disabled and thus don’t have the capacity to have a say. The third tactic Sinclair noted was to appeal to prejudice. Claiming that the advocator doesn’t know what is best for themselves, and thus need to have their agency stripped from them in favor of what “normal” people think is best. 67 Some criticism has come from autistic people themselves, suggesting that the majority of the Autistic people in the Neurodiversity movement have a less severe form of the condition and that the parents who adopted pro-cure attitudes are not monsters who want to torture their kids, but are merely parents that feel overwhelmed by the more extreme and disabling aspects of autism. Autism is a spectrum disorder, so these complaints have a point. But just because the Neurodiversity movement is not desperately scrambling for a total cure, does not mean that they don’t want to mitigate the uglier aspects of the condition. On the contrary, the neurodiversity movement seeks to improve access to the essential services necessary for all Autistic people, especially those with higher needs.68 The movement is not asking for disruptive behaviors like hurting others to become acceptable, but that actions considered “weird” such as hand flapping, playing by oneself, or rocking back and forth should be, if the actions are not hurting the person doing them.69

Conclusion

Ultimately, Autism remains a stigmatized neurological difference. A society’s understanding and treatment of an Autistic person can still be influenced by a variety of factors. For example, those of lower socio-economic standing, low-English proficiency groups, and those belonging to a racial minority have a harder time accessing the resources for Autistic people in the United States. Members of these groups might even not be diagnosed, further delaying helpful practices.70 This is not even getting into how an African-American parent of an autistic child might encounter racist assumptions that they aren’t capable of providing a good home for or understanding their child. 71 For instance, Michael D. Hannon’s article “Acknowledging Intersectionality: An Autoethnography of a Black School Counselor Educator and Father of a Student with Autism” highlights this through its telling of a meeting discussing his autistic son’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP),

“My wife and I wanted to maintain the range of services indicated in his current individualized education plan, but the school felt differently. They believed his school performance data (e.g., grades, standardized test scores, teacher reports) justified less support. He was doing really well, they said. On our scheduled meeting date… My wife and I were ushered to a conference meeting room with our son’s predominantly White faculty, specialists, and administrators. While neither of us wanted to present as being pushy, aggressive, or contrary, we agreed to firmly advocate for the broadest range of educational services… I was sitting next to my son’s White female language arts teacher during this meeting. At one point, we disagreed about a consequence for missing an assignment. At that specific moment, I recalled with others in attendance her telling me that if my son did not fully complete assignments, he would be penalized. I communicated that his being penalized failed to acknowledge how his executive functioning challenges contribute to submitting an incomplete assignment as a result of misunderstanding multi-step directions. She retorted by saying she never communicated he would be penalized. As I continued to challenge her recollection, she raised her voice, interrupted, and over-talked me, and asserted I was absolutely wrong. I considered the implications if I took the same posture with her. Doing so put me at risk of being perceived as aggressive or hostile. No one in the room acknowledged her aggressive behavior….their entire team was resolved that his IEP needed to change and that the change would be made. This was when I realized my invisible status… I was an invisible Black father, and we were invisible Black parents who needed to comply with the school’s position.” Hannon’s input was only acknowledged when he threatened to use his connections as faculty member of a state institution’s College of Education and Human services and his knowledge of special education to file a complaint to the state’s board of education.72 There is also a difference in stigma levels between countries. For example, in South Korea, autistic children are informally classified as “border children,” so as to avoid the stigma from autism that could result in a person’s failure to reach the cultural value of educational success. In certain parts of Africa, Autism is considered a sign of supernatural phenomenon, resulting in an autistic individual being more harshly stigmatized, such as being asked to leave public transport, or even subjected to dangerous “cures.” 73 The cultural contexts of these communities and their influence on Autism stigma would be better researched by either a native of said culture, or by someone who has more experience in said culture. However, as illustrated throughout this article, Autistic people have formed their own communities and fought back. As the diagnostic criteria for autism shifts and changes, the rate of autism diagnosis will similarly shift, growing or receding. In any case, between Autistic activism online and in the physical world, hopefully people like Alex, Misha, Sinclair, and others won’t be seen as mentally disabled people who need fixing, but as individuals with different ways of thinking to be appreciated. In the meantime, what can the average person do? Well, just reading about autism and being more knowledgeable is a good start. According to Jannessa L. Kitchin and Nancy J. Karlin in a 2022 study, knowing about autism treatments, knowing that there is no known cause of autism, or even just knowing someone with autism decreases the likelihood of a person to endorse autism stigma. 74 There are a plethora of Autistic advocacy websites that feature Autistic people telling their stories, such as Autism Network International or the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. There are countless of videos by Autistic people explaining their experience with the condition. Some of this advice can be applied to humanity in general. If a person does not know about a group, culture, or identity, hearing the perspectives of a person from that community will be helpful.

- Name changed to protect identity ↵

- “Autism Spectrum Disorder.” In DSM-5, 50–52. Washington, DC London, England: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. https://ia902503.us.archive.org/11/items/APA-DSM-5/DSM5.pdf. ↵

- Frasier-Robinson, Michele, and Aimee Graham. “Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Guide to the Latest Resources.” Reference & User Services Quarterly 55, no. 2 (2015), 113. ↵

- “Autism Spectrum Disorder.” In DSM-5, 50–52. Washington, DC London, England: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. https://ia902503.us.archive.org/11/items/APA-DSM-5/DSM5.pdf. ↵

- Raymaker, Dora M. “Shifting the System: AASPIRE and the Loom of Science and Activism.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 164. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Eberly, Susan Schoon. “Fairies and the Folklore of Disability: Changelings, Hybrids and the Solitary Fairy.” Folklore 99, no. 1 (1988), 62–68. ↵

- Fitzgerald, Michael M. “The History of Autism in the First Half Century of the 20th Century: New and Revised.” Journal for ReAttach Therapy and Developmental Diversities 1, no. 2 (2018), 71. ↵

- Mogro-Wilson, Cristina, and Kay Davidson. “Autism Spectrum.” In Handbook of Social Work Practice with Vulnerable and Resilient Populations, edited by Alex Gitterman, 3rd ed., 74. Columbia University Press, 2014. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/gitt16362.8. ↵

- Fitzgerald, Michael M. “The History of Autism in the First Half Century of the 20th Century: New and Revised.” Journal for ReAttach Therapy and Developmental Diversities 1, no. 2 (2018), 72. ↵

- Kanner, Leo. “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact.” Nervous Child: Journal of Psychopathology, Psychotherapy, Mental Hygiene, and Guidance of the Child 2 (1943), 241–46. ↵

- Carlson, Marla. “Performing with Autists.” In Affect, Animals, and Autists, 127–28. Feeling Around the Edges of the Human in Performance. University of Michigan Press, 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.9209652.8. ↵

- Mogro-Wilson, Cristina, and Kay Davidson. “Autism Spectrum.” In Handbook of Social Work Practice with Vulnerable and Resilient Populations, edited by Alex Gitterman, 3rd ed., 74. Columbia University Press, 2014. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/gitt16362.8. ↵

- Rosen, Nicole E., Catherine Lord, and Fred R. Volkmar. “The Diagnosis of Autism: From Kanner to DSM-III to DSM-5 and Beyond.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 51, no. 12 (2021), 4258. ↵

- Rosen, Nicole E., Catherine Lord, and Fred R. Volkmar. “The Diagnosis of Autism: From Kanner to DSM-III to DSM-5 and Beyond.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 51, no. 12 (2021), 4254–55. ↵

- Prochnow, Alexandria. “An Analysis of Autism Through Media Representation.” ETC: A Review of General Semantics 71, no. 2 (2014), 139–40. ↵

- Hattenstone Simon. “‘Why Do They Have to Be Brilliant?’ The Problem of Autism in the Movies; Over 30 Years since Dustin Hoffman Twitched His Way to an Oscar in Rain Man, Our Experts Give Their Verdict on a Season of Portrayals of the Neurodiverse, from Sia’s Music to What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? – Document – Gale General OneFile.” The Guardian, September 15, 2021. ↵

- Baker, Anthony D. “Recognizing Jake: Contending with Formulaic and Spectacularized Representations of Autism in Film.” In Autism and Representation, edited by Mark Osteen, 229–34. Routledge Research in Cultural and Media Studies. 12. 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016: Routledge, 2008. ↵

- Draaisma, Douwe. “Stereotypes of Autism.” Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 364, no. 1522 (2009), 1478–79. ↵

- Baker, Anthony D. “Recognizing Jake: Contending with Formulaic and Spectacularized Representations of Autism in Film.” In Autism and Representation, edited by Mark Osteen, 234–37. Routledge Research in Cultural and Media Studies. 12. 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016: Routledge, 2008. ↵

- Mittmann, Gloria, Beate Schrank, and Verena Steiner-Hofbauer. “Portrayal of Autism in Mainstream Media – a Scoping Review about Representation, Stigmatisation and Effects on Consumers in Non-Fiction and Fiction Media.” Current Psychology, July 22, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04959-6. ↵

- Akhtar, Nameera, Janette Dinishak, and Jennifer L. Frymiare. “Still Infantilizing Autism? An Update and Extension of Stevenson et al. (2011).” Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management 4, no. 3 (September 1, 2022), 224–32. ↵

- Rosenblatt, Adam. “Autism, Advocacy Organizations, and Past Injustice.” Disability Studies Quarterly 38, no. 4 (December 21, 2018). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v38i4.6222. ↵

- Robison, John Elder. “My Time with Autism Speaks.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 247–48. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Rosenblatt, Adam. “Autism, Advocacy Organizations, and Past Injustice.” Disability Studies Quarterly 38, no. 4 (December 21, 2018). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v38i4.6222. ↵

- Robison, John Elder. “My Time with Autism Speaks.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 248–52. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Rosa, Shannon Des Roches. “Things Left Unsaid: ‘I Am Autism’ 10 Years Later.” THINKING PERSON’S GUIDE TO AUTISM, September 13, 2019. https://thinkingautismguide.com/2019/09/things-left-unsaid-i-am-autism-10-years.html. ↵

- I Am Autism Commercial by Autism Speaks, 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UgLnWJFGHQ. ↵

- Rosa, Shannon Des Roches. “Things Left Unsaid: ‘I Am Autism’ 10 Years Later.” THINKING PERSON’S GUIDE TO AUTISM, September 13, 2019. https://thinkingautismguide.com/2019/09/things-left-unsaid-i-am-autism-10-years.html. ↵

- Liss, Jennifer. “Autism: The Art of Compassionate Living.” WireTap Magazine, July 11, 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20080523223522/http:/wiretapmag.org/education/38631. ↵

- Rosa, Shannon Des Roches. “Things Left Unsaid: ‘I Am Autism’ 10 Years Later.” THINKING PERSON’S GUIDE TO AUTISM, September 13, 2019. https://thinkingautismguide.com/2019/09/things-left-unsaid-i-am-autism-10-years.html. ↵

- Robison, John Elder. “My Time with Autism Speaks.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 253. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Autism Speaks. “Questions and Answers.” Accessed March 18, 2024. https://www.autismspeaks.org/autism-speaks-questions-answers-facts. ↵

- Shute, Nancy. “Desperate for an Autism Cure.” Scientific American 303, no. 4 (2010), 83. ↵

-

Summers, John. “Autism’s Cult of Redemption.” Skeptic 28, no. 4 (October 1, 2023), 28–36. ↵

- Shute, Nancy. “Desperate for an Autism Cure.” Scientific American 303, no. 4 (2010): 83. ↵

- Offit, Paul A. “Death of an Autistic Child From Chelation Therapy – Op-Ed.” Parents Pack, September 1, 2005. https://www.chop.edu/news/death-autistic-child-chelation-therapy-oped. ↵

- Summers, John. “Autism’s Cult of Redemption.” Skeptic 28, no. 4 (October 1, 2023), 34–35. ↵

- Neumeier, Shain M., and Lydia X. Z. Brown. “Torture in the Name of Treatment: The Mission to Stop the Shocks in the Age of Deinstitutionalization.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 216–17. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “How We Got To This Place.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 25–29. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Neumeier, Shain M., and Lydia X. Z. Brown. “Torture in the Name of Treatment: The Mission to Stop the Shocks in the Age of Deinstitutionalization.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 216–17. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “How We Got To This Place.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 26–27. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “The Food and Drug Administration Permits the Use of Electric Shock on People with Disabilities.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 141–43. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “Staging the Next Battleground.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 186–89. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “The Food and Drug Administration Permits the Use of Electric Shock on People with Disabilities.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 150–52. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “The Food and Drug Administration Permits the Use of Electric Shock on People with Disabilities.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 150–52. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- “Milliamps to Volts – CalculatorMix.” Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.calculatormix.com/conversions/electrical/milliamps-volts/. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “The Food and Drug Administration Permits the Use of Electric Shock on People with Disabilities.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 150–52. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “Chronology.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 331–34. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “A Long Story.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 1–6. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “Bad Faith or Responsible Government? Another Attempt to Limit the Use of Aversives.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 219–20. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Neumeier, Shain M., and Lydia X. Z. Brown. “Torture in the Name of Treatment: The Mission to Stop the Shocks in the Age of Deinstitutionalization.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 216–17. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Nisbet, Jan. “Chronology.” In Pain and Shock in America: Politics, Advocacy, and the Controversial Treatment of People with Disabilities, 336–38. Waitham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2021. ↵

- Latine is a gender natural term for Latino/as. It’s usage here instead of Latinx is due to Latine coming directly from the Spanish speaking world, and because it is easier to pronounce for Spanish speakers. McGee, Vanesha. “Latino, Latinx, Hispanic, or Latine? Which Term Should You Use? | BestColleges.” Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/hispanic-latino-latinx-latine/. ↵

- Brown, Lydia X. Z. “There Is No Abolition or Liberation without Disability Justice.” In FUTURE/PRESENT, edited by Daniela Alvarez, Roberta Uno, and Elizabeth M. Webb, 224. Arts in a Changing America. Duke University Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.10121667.41. ↵

- Neumeier, Shain M., and Lydia X. Z. Brown. “Torture in the Name of Treatment: The Mission to Stop the Shocks in the Age of Deinstitutionalization.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 219–20. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Mogro-Wilson, Cristina, and Kay Davidson. “Autism Spectrum.” In Handbook of Social Work Practice with Vulnerable and Resilient Populations, edited by Alex Gitterman, 3rd ed., 84. Columbia University Press, 2014. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/gitt16362.8. ↵

- Turnock, Alice, Kate Langley, and Catherine R.G. Jones. “Understanding Stigma in Autism: A Narrative Review and Theoretical Model.” Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management 4, no. 1 (March 1, 2022), 82. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0005. ↵

- Bagatell, Nancy. “From Cure to Community: Transforming Notions of Autism.” Ethos 38, no. 1 (2010), 34–36. ↵

- Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities. “Parallels In Time | A History of Developmental Disabilities | Part One.” MN Department of Administration. Accessed March 24, 2024. https://www.mn.gov/mnddc/parallels/seven/7b/1.html. ↵

- Bagatell, Nancy. “From Cure to Community: Transforming Notions of Autism.” Ethos 38, no. 1 (2010), 36. ↵

- In the source cited, Jim Sinclair is described with Xe/Xim, which are neo-pronouns for people who don’t identify with either side of the traditional gender binary. While I don’t know why Sinclair chose Xe/Xim over the more conventional and understandable They/Them, I will use the pronouns described out of respect. Devin-Norelle. “Gender-Neutral Pronouns 101: Everything You’ve Always Wanted to Know.” Them, May 22, 2020. https://www.them.us/story/gender-neutral-pronouns-101-they-them-xe-xem. ↵

- Pripas-Kapit, Sarah. “Historicizing Jim Sinclair’s ‘Don’t Mourn for Us’: A Cultural and Intellectual History of Neurodiversity’s First Manifesto.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 37–49. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Sinclair, Jim. “History of ANI.” Autism Network International, January 2005. https://www.autreat.com/History_of_ANI.html. ↵

- Bagatell, Nancy. “From Cure to Community: Transforming Notions of Autism.” Ethos 38, no. 1 (2010): 36–37. ↵

- Mittmann, Gloria, Beate Schrank, and Verena Steiner-Hofbauer. “Portrayal of Autism in Mainstream Media – a Scoping Review about Representation, Stigmatisation and Effects on Consumers in Non-Fiction and Fiction Media.” Current Psychology, July 22, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04959-6. ↵

- Evans, Meg. “The Autistic Genocide Clock.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 141–49. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Sinclair, Jim. “History of ANI.” Autism Network International, January 2005. https://www.autreat.com/History_of_ANI.html. ↵

- Ginny, Russell. “Critiques of the Neurodiversity Movement.” In Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline., edited by Steven K. Kapp, 316–19. Portsmouth, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. ↵

- Bagatell, Nancy. “From Cure to Community: Transforming Notions of Autism.” Ethos 38, no. 1 (2010), 47–48. ↵

- Malomet, Maayan. “Disparities in Care.” In Occupational Therapists’ Stigma toward Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Focus on Socioeconomic Status and English-Language Proficiency, 5. Muhlenberg College. Accessed March 24, 2024. https://jstor.org/stable/community.31080979. ↵

- Turnock, Alice, Kate Langley, and Catherine R.G. Jones. “Understanding Stigma in Autism: A Narrative Review and Theoretical Model.” Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management 4, no. 1 (March 1, 2022), 81. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0005. ↵

- Hannon, Michael D. “Acknowledging Intersectionality: An Autoethnography of a Black School Counselor Educator and Father of a Student with Autism.” The Journal of Negro Education 86, no. 2 (2017), 154–58. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.2.0154. ↵

- Turnock, Alice, Kate Langley, and Catherine R.G. Jones. “Understanding Stigma in Autism: A Narrative Review and Theoretical Model.” Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management 4, no. 1 (March 1, 2022): 81. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0005. ↵

- Kitchin, Jannessa L., and Nancy J. Karlin. “Awareness and Stigma of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Undergraduate Students.” Psychological Reports 125 (2022), 2072–83. ↵

Tags from the story

autism

Neurodiversity

Nomination-Academic-Explanatory

Nomination-Social-Sciences

Trenton Boudreaux

I am a born and raised Texan! I am currently enrolled at St Mary’s University – San Antonio. I am majoring in History with a minor in Creative Writing. I appreciate learning historical facts from around the world. When traveling, I look forward to exploring local historical sites and museums. I first realized my talent for creative writing in middle school. My hope is to one day become a fiction author and write fantasy novels inspired by events in history.

Author Portfolio PageRecent Comments

Vianna Villarreal

Very effective and heart felt topic. This is so interesting to learn about especially with autism being such a large spectrum. It is not always going to look the same in every case or have the same outcome compared to others. So just seeing ways people can better understand or better educate themselves through acknowledging this is so important for society. We must remember autism for being uncontrollable and something we must learn to accommodate with.

24/04/2024

7:41 pm

Joseph Reed

I am glad that you wrote this article in order to bring more awareness to autism and the history behind it; while I had known some of the stigma and such surrounding autism, I did not know the full extent of the discrimination, and as well as this, I did not realize that the more egregious negative perceptions and actions towards autistic people were occurring so recently; within the past decade. It seems that there is a lot of work to be done yet, with regards to reducing negative perceptions and stigma. But, at least progress is being made, and with education and awareness, perhaps this goal can be achieved one day.

26/04/2024

7:41 pm

Jonathan Flores

Wow, this article is extremely interesting and well written. First, I must compliment how well you structured your ideas and developed them throughout this very in-depth article. In addition, you expertly covered a complex topic of science that is still developing today. In this way, I appreciate how you challenged preconceived notions, and demonstrated the evolving approach to Autism through your style. Congratulations on publishing and good job.

24/04/2024

7:41 pm