The History of the New Orleans Flood Infrastructure

On September 9, 1965, Hurricane Betsy hit New Orleans, exposing vulnerabilities in the flood mitigation infrastructure, leading to major flooding, loss of life, and property damage 8. The crisis was further exacerbated by the widespread failure of the city’s pumping system. Designed only to remove water from the city at a steady level, the pumping system was immediately overwhelmed by the full force of a 10-foot storm surge that delivered a water input thousands of times greater than the designed output capacity. The situation was worsened further by the complete failure of New Orlean’s electrical grid, rendering any remaining pumps inoperable, leaving the city to fill with water. Ultimately the widespread failure of the infrastructure in the aftermath of hurricane Betsy was no surprise. Vulnerabilities in the flood infrastructure were known by the USACE, but the required standards, procedures, and design requirements were bypassed which made any pre-existing flaws acceptable.

In the wake of hurricane Betsy, the Flood Control Act of 1965 was enacted, ironically reinstituting the USACE with the same responsibility again, to design and construct an improved flood protection system against future hurricane threats, adhering to strict protocols and procedures this time. Thus, the USACE began to build a network of levees and flood-walls that were higher and stronger than earlier versions, creating a continuous barrier against storm surges. The project was estimated to take 13 years to complete, but began to experience significant issues almost immediately. The original $85 million budget ballooned to more than $738 million due to inflation and design changes. Combined with large funding cuts, 60-90% of the project was estimated to be completed by 2005, well after the 13-year schedule called for initially. Ultimately, by 2004, for the first time in 37 years, federal budget cuts had all but stopped major work on the New Orleans area’s east bank hurricane levee’s 9. Furthermore, by 2oo5 proposed budget cuts provided almost $300 million less in funding to the USACE that was needed to complete critical infrastructure improvements in and around New Orleans 10 . Thus, yet again, the USACE failed to build a system that would protect New Orleans against future storms due to budget and funding issues, leaving the city’s residents unaware of how vulnerable they were, until Hurricane Katrina began to form.

Set for Failure: The Arrival of Hurricane Katrina

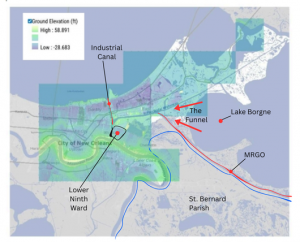

Following these two significant breaches to New Orleans flood protection levees, Hurricane Katrina began to make its initial landfall on the southeast coast of Louisiana at 6:10am. Despite having weakened from its peak intensity, Katrina made landfall as a high-end Category 3 hurricane with sustained wind speeds of 125mph. Due to it’s exceptionally large size, 400 miles wide, the entirety of the south eastern Louisiana coastline, including New Orleans, was now in the destructive path of the storm. At approximately 6:30am, Katrina pushed a 14-17 foot surge of seawater into the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet (MRGO) and Lake Borgne. Once entering, these two storm surges converged in eastern New Orleans, in an area known as “The Funnel” (Fig.3) where the levee system narrowed significantly an headed towards the Industrial Canal.

This intense pressure began to compromise the Industrial Canal’s structure integrity. The flood waters eroded the earthen embankments, causing concrete I-walls to bulge and tilt. The movement created cracks in the soil foundation, allowing water to seep underneath and cause the levees to fail. By 7:45 in the morning, the levees on the canal’s eastern side breached “explosively”, unleashing a wave of water nearly 20-feet high that destroyed houses and rapidly submerged the Ninth Ward. As the storm’s eye passed over, the winds shifted, driving a massive surge from Lake Pontchartrain directly into the city’s drainage canals, setting the stage for the levee failures in the London Avenue Canal and the 17th Street Canal, both which are located in the northern part of New Orleans where they run through residential areas to discharge water into lake Pontchartrain. These catastrophic levee failures finally sealed New Orlean’s fate15. Designed to protect the city from similar surges to those of Hurricane Betsy, Katrina’s storm surge quickly surpassed expectations and design limits, and the complex system of flood control systems failed to protect the residents of New Orleans.

Institutional Collapse

Bureaucratic Red Tape

After the collapse of communication between government officials and the state, and FEMA’s failure to provide enough resources, supplies, and food to the survivors of hurricane Katrina, several private companies and foreign countries took initiative and began deploying aid to the state of Louisiana to mitigate the humanitarian crisis. Companies such as Walmart and Home Depot sent millions of dollars worth of supplies to the survivors of Hurricane Katrina, but were faced with FEMA’s bureaucratic red tape. Similarly, the U.S received millions of dollars in aid from foreign countries, but turned down at least 54 of the 77 aid offers24. This was due to the strict national response framework at the time, which proved to be far too bureaucratic to support the response of a catastrophe25, and lacked the necessary policies and procedures to ensure the proper acceptance and distribution of in-kind assistance donated by foreign countries and militaries. As a result of the government’s inability to process foreign aid and resources, food, MRE’s (Meal, Ready-To-Eat), water, and medical supply shipments were left outside in the elements, where they were wasted and no longer usable. But, the waste of resources did not end there. Thousands of volunteers ranging from medical professionals, search and rescue personnel, to civilians, were turned away when they showed up in New Orleans to help in relief operations. Volunteers were turned away due to their names not being on a pre-registration sheet, a process that required numerous time-consuming approval signatures and data processing steps26, hindering the deployment of people to assist in rescue and recovery efforts. The muddled response to a dynamic event like Hurricane Katrina highlighted how adherence to a strict bureaucratic process can paralyze disaster relief efforts by preventing life-saving supplies from reaching people most in need – a natural disaster can be turned into a bureaucratic catastrophe through institutional failures.

Long Lasting Effects

Now, more than twenty years later, the devastation that occurred during Hurricane Katrina has left a scar on the City of New Orleans and its residents. The storm highlighted the flawed engineering, institutional failures, and the political neglect of the local and federal government. The location of New Orleans and the destruction of Hurricane Betsy in 1965 had moved local and federal government to develop a complex system of pumps, canals, and levees to protect the city. But, decades of chronic underfunding , design shortcuts, and political influence, left New Orleans to fend for itself in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina with an incomplete and structurally vulnerable system. Structurally vulnerable levees protecting New Orleans were not built for the most severe hurricanes 27. Levees such as those on the east side of the London Avenue Canal failed due to sheet pilings not being driven deep enough to cut off under seepage through the sand underlying the canal and levee28. This flaw in implementing the design allowed the bottom sediments to erode and uplift the sheet pilings during a massive storm like Katrina. This immediate engineering failure set the stage for the devastating institutional collapse of New Orleans local government and FEMA, paralyzing command and control at all levels and delaying relief 29 efforts within the city. New Orleans local government’s lack of push for evacuations played a significant role in the institutional collapse of FEMA. Ray Nagin, New Orleans’s Mayor at the time, was aware of the impending hurricane and was warned 56 hours before the arrival of Katrina to order mandatory evacuations. But, the local government failed to enforce evacuations, leading to the loss of thousands in the wake of Katrina, as evacuations were enforced only 19 hours before landfall, 30 when Katrina was at the city’s doorstep. As a result, a massive humanitarian crisis arose, as those who remained in the city were left without homes, power, and food. FEMA’s logistic system quickly became overwhelmed as a result, making it challenging to get supplies, equipment, and personnel 31 where needed. Together, the collapse of local law enforcement and lack of public communications 32, paved the path to FEMA’s collapse when it was needed the most.

Ultimately, Katrina served as a tragic lesson; the integrity of a city’s infrastructure designed to protect against natural disasters and the government response towards the disaster is crucial when it comes to the level of preparedness needed to address a catastrophe. Due to the accuracy and and timeliness of the National Weather Service and National Hurricane Center forecasts, further loss of life was prevented, 33 while FEMA was completely dysfunctional due to the failures in leadership, and a poor National Response framework that proved to be too bureaucratic for the demands of the disaster.

Hurricanes will continue to hit the region in the future – the impacts of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 highlight the importance of continued vigilance to develop robust, well-integrated, and well-funded plans for responding to the next significant natural disaster.

- Wikimedia Commons. accessed 2025 Dec 1. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=A+GOES-12+visible+image+of+Hurricane+Katrina+shortly+after+landfall+on+August+29%2C+2005&title=Special%3AMediaSearch&type=image. ↵

- National Archives. 2018. Hurricane Katrina | George W. Bush Library. wwwgeorgewbushlibrarygov. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.georgewbushlibrary.gov/research/topic-guides/hurricane-katrina. ↵

- Hurricane Katrina summary | Britannica. 2025 Sep 9. accessed 2025 Nov 5 ↵

- New Orleans 1841 1880 map.jpg – Wikimedia Commons. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_Orleans_1841_1880_map.jpg. ↵

- Hazards. Infrastructure Failure-Levee Failure – NOLA Ready. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://ready.nola.gov/hazard-mitigation/hazards/infrastructure-failure-levee-failure/ ↵

- Hazards. Infrastructure Failure-Levee Failure – NOLA Ready. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://ready.nola.gov/hazard-mitigation/hazards/infrastructure-failure-levee-failure/ ↵

- Hazards. Infrastructure Failure-Levee Failure – NOLA Ready. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://ready.nola.gov/hazard-mitigation/hazards/infrastructure-failure-levee-failure/ ↵

- Hurricane Betsy. 2013 Oct 15. Coastal Protection And Restoration Authority. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://coastal.la.gov/timeline/hurricane-betsy/. ↵

- A Brief History of Bush Cuts to Flood Control | Levees Not War. accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://www.leveesnotwar.org/a-brief-history-of-bush-cuts-to-flood-control/#:~:text=The%20next%20year%20.%20.%20.%20the,area’s%20east%20bank%20hurricane%20levees. ↵

- A Brief History of Bush Cuts to Flood Control | Levees Not War. accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://www.leveesnotwar.org/a-brief-history-of-bush-cuts-to-flood-control/#:~:text=The%20next%20year%20.%20.%20.%20the,area’s%20east%20bank%20hurricane%20levees. ↵

- City of New Orleans Map. accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://gis.nola.gov/apps/bfe_lookup/ ↵

- NOVA | Storm That Drowned a City | How New Orleans Flooded (non-Flash) | PBS. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/orleans/how-nf.html. ↵

- NOVA | Storm That Drowned a City | How New Orleans Flooded (non-Flash) | PBS. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/orleans/how-nf.html. ↵

- NOVA | Storm That Drowned a City | How New Orleans Flooded (non-Flash) | PBS. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/orleans/how-nf.html ↵

- NOVA | Storm That Drowned a City | How New Orleans Flooded (non-Flash) | PBS. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/orleans/how-nf.html. ↵

- ioerror. 2005. English: New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina Disaster. Sign on balcony “HELP NO FOOD NO WATER.” accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Driving_through_New_Orleans_after_Hurricane_Katrina_Disaster_Help_Sign.jpg. ↵

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) | Homeland Security. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.dhs.gov/employee-resources/federal-emergency-management-agency-fema. ↵

- A failure of Initiative. accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/katrina/govdocs/109-377/execsummary.pdf ↵

- Author T. FEMA Failures in Katrina Aftermath Serve as Stark Warning | Sierra Club. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/fema-failures-katrina-aftermath-serve-stark-warning. ↵

- Author T. FEMA Failures in Katrina Aftermath Serve as Stark Warning | Sierra Club. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/fema-failures-katrina-aftermath-serve-stark-warning. ↵

- Hurricane Katrina: Lessons Learned – Chapter Four: A Week of Crisis (August 29 – September 5). accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/reports/katrina-lessons-learned/chapter4.html#:~:text=As%20a%20result%2C%20local%2C%20State,of%20what%20was%20occurring%20in ↵

- Cato.org. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.cato.org/blog/hurricane-katrina-remembering-federal-failures#:~:text=The%20House%20report%20found%20that,a%20lack%20of%20system%20interoperability ↵

- Cato.org. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.cato.org/blog/hurricane-katrina-remembering-federal failures#:~:text=The%20House%20report%20found%20that,a%20lack%20of%20system%20interoperability ↵

- admin. 2007 Apr 30. Report: U.S. Turned Away Foreign Aid Offered After Hurricane Katrina. Insurance Journal. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/national/2007/05/01/79164.html ↵

- Hurricane Katrina: Lessons Learned – Chapter Five: Lessons Learned. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/reports/katrina-lessons-learned/chapter5.html#:~:text=The%20National%20Response%20Plan’s%20Mission,the%20response%20to%20a%20catastrophe ↵

- Hurricane Katrina: Lessons Learned – Chapter Five: Lessons Learned. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/reports/katrina-lessons-learned/chapter5.html#:~:text=The%20National%20Response%20Plan’s%20Mission,the%20response%20to%20a%20catastrophe. ↵

- A failure of Initiative. accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/katrina/govdocs/109-377/execsummary.pdf ↵

- Lessons Learned & Reducing Vulnerability. accessed 2025 Nov 30. https://www2.tulane.edu/~sanelson/New_Orleans_and_Hurricanes/lessons_learned-reducing_vulnerability.htm#:~:text=Failure%20of%20the%20levee%20on,Figure%206. ↵

- A failure of Initiative. accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/katrina/govdocs/109-377/execsummary.pdf ↵

- A failure of Initiative . accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/katrina/govdocs/109-377/execsummary.pdf ↵

- A failure of Initiative . accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/katrina/govdocs/109-377/execsummary.pdf ↵

- A failure of Initiative . accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/katrina/govdocs/109-377/execsummary.pdf ↵

- A failure of Initiative. accessed 2025 Dec 2. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/katrina/govdocs/109-377/execsummary.pdf ↵