Two hundred years after Frankenstein’s release, scholars and casual readers alike continue to study Mary Shelley’s most prominent work. On the surface, Frankenstein is simple horror: a gruesome monster turns against the scientist who created him and attacks his creator’s loved ones. One could argue that Shelley intended to warn readers against hubris, and that pushing outside the natural boundaries of science has consequences. However, a closer examination of the text reveals a social commentary in addition to the scientific one. Rather than begin Victor Frankenstein’s tale with his creation of the Monster, Shelley introduces the scientist as a dying man.1 The ailing scientist first reflects back on the events of his early years: his mother’s death and time spent with Elizabeth, a childhood companion who Victor later marries. As the story progresses, Shelley depicts not just the aftermath of the Monster’s attacks, but his interactions with Victor that precede the violence. When taken together, these moments weave a cautionary tale deeper than the apparent scientific warnings. In Victor’s treatment of the Monster, as well as the text’s depiction of women, Shelley paints a world in which the privileged class handles the outsider with disdain, and, in doing so, faces dire consequences.

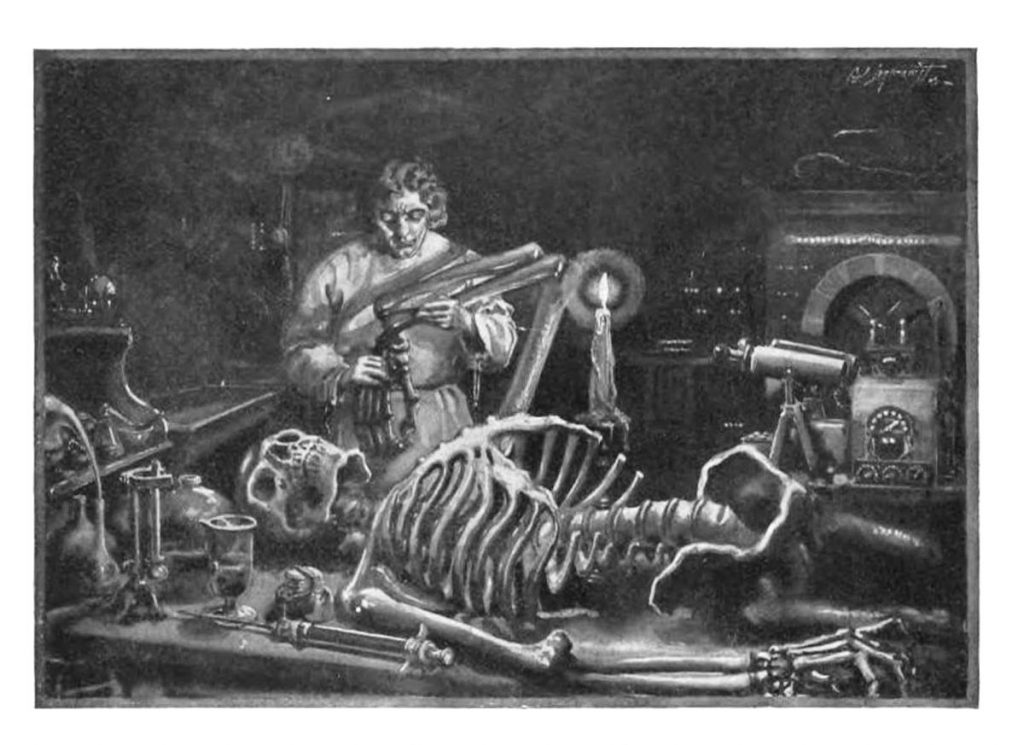

To fully grasp Shelley’s intent in Victor’s treatment of the Monster, the reader must first consider who Victor is before he brings the Monster to life. In the first seconds of his tale, Victor states that his “family is one of the most distinguished” in Geneva.2 Even when he moves away to school, the young man has a “servant” available to wait on him.3 Furthermore, by pursuing education, Victor seeks “to join the new class of learned men” who “replaced the landed gentry as the upper society in Europe.”4 Through both heredity and action, Victor manifests the privileged class. Of course, the Monster does commit atrocities throughout Frankenstein, but not in his first living moments; if the Monster were inherently evil, he would have killed Victor when he was first brought to life. Therefore, any interaction between the two should not be viewed as man versus creature, but rather as a privileged being versus an outsider.With this context in mind, Victor’s treatment of his creation is clearly problematic. In perhaps the text’s most gripping moment, Victor marvels at the Monster as “the shriveled complexion and straight black lips” come alive. “Beautiful!” Victor exclaims.5 He dwells on every aspect of the Monster’s appearance, amazed at his own handiwork until he sours at the “horrid contrast” between the Monster’s “teeth” and “watery eyes.”6 In this scene, Victor never considers that he has somehow usurped the natural order or even that the Monster might turn out to be evil. He simply dotes on the physical appearance of his creation. So, when Victor “rushe[s] out of the room,” it is because he is disgusted by the pure physicality of the Monster, and not because of some terrifying moral epiphany.7

Aside from Victor’s initial fright—which would be understandable were he not the Monster’s creator—his aversion to his own creation never improves. Following the murder of Victor’s younger brother, William, Victor returns home to Geneva and eventually travels to Mont Blanc. As Victor navigates “the field of ice” at the mountain’s base, the monster appears, confronts Victor, and convinces his creator to follow him into a hut.8 Here, Victor asserts that he now understands “the duties of a creator towards his creation,” and this statement might seem true, considering Victor finally speaks with and listens to the creature.9 However, one must also consider that the Monster is both physically more powerful than Victor and Victor believes the Monster has murdered young William, suggesting that Victor never really has a choice in accompanying his creation. Once inside the hut, the Monster details his failed encounters with humans since he last saw his maker, and finally begs Victor to create a second life so that he may have a companion. Victor initially complies, believing that with a mate, the two creatures may find solace together away from Europe.10 While conflicted about bringing a second life into the world, Victor only rips apart the lifeless body of this creation when he sees his first creature staring in through the laboratory window.11 In this series of interactions between the young scientist and his creation, Victor is always motivated by the Monster’s appearance rather than by his actions.

In addition to the major plot events involving Victor, Shelley uses two subtle moments to comment on the Monster’s place in society. Scholar Anne Mellor explains, “only two characters…do not immediately interpret the creature as evil.”12 The blind Father De Lacey, who the monster tells Victor he encountered during his travels, cannot evaluate the Monster’s appearance. And the ship captain, Walton, who finds the dying Victor at the story’s very beginning, hears Victor’s description of the Monster before meeting him. Both men treat the creature with kindness.13 While neither of these characters advances the main narrative forward in the manner Victor does, they both depict a humane response to the creature, and, in doing so, highlight Victor’s cruelty towards his own creation. Unlike Father De Lacey and Walton who come away from their encounters with the Monster unscathed, Victor faces extreme consequences for abusing his creation. Indeed, Victor’s family is both literally and figuratively torn apart by the Monster. And, upon finally deciding to rid the world of his creation, Victor chases the Monster into the Arctic, where he is consumed by the hostile elements and eventually “sinks…into apparent lifelessness.”14 In essence, Victor manifests privilege; he is born into an influential household and receives opportunities others cannot. Contrarily, Victor’s creation is jerked into a hostile world where he is judged entirely by his appearance. Victor’s treatment of his creation—the outsider—is motivated entirely by the superficial trappings of physical appearance, a trap that ends in disaster for Victor and thereby the upper class he represents.

Underneath the plot’s surface lies a less obvious but equally important commentary on how humans treat one another. “Frankenstein,” authors Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler assert, “is a novel of male voices.”15 Indeed, this novel relies on three different narrators—all of whom are male—and focuses almost entirely on male characters. As “many Gothic novels…written by women” feature a “heroine rather than a hero,” the reader must examine why Mary Shelley would relegate women in Frankenstein to the background.16 Two sections in this novel should be of particular interest to the reader. First, as a child, Victor does express interest in science, but he does not progress from reading to experimentation until later; immediately after his mother dies, he departs for the “all-male world of the university.”17 Once at Ingolstadt, isolated “from the feminine” influence that defined his childhood, Victor falls into the dark world of pushing outside science’s moral boundaries.18 Secondly, while Victor loves Elizabeth enough to marry her, she remains absent for most of the text, providing almost no value to the narrative until the end. Once the Monster kills Elizabeth, Victor finally resolves to destroy his creation. Therefore, Elizabeth’s only significant contribution to the text is as a passive recipient of another character’s action.

While one could argue that the lack of female representation in Frankenstein constitutes nothing more than Shelley’s desire to highlight the struggle between Victor and his creation, this argument fails to examine Shelley’s other options as an author as well as the context in which the book was written. Were Shelley only concerned with the scientific aspects of Frankenstein, she would have begun Victor’s narrative in a far more interesting place than his childhood, perhaps in the morgue searching for limbs to fuse together. Furthermore, the Monster’s first murder could have just as easily provoked Victor to action. These alternatives delineate that Shelley’s choice to include Victor’s mother and Elizabeth’s murder in the narrative was a deliberate one. Furthermore, it was “a common convention for women writers” in the early nineteenth century to publish their work anonymously as Mary Shelley did with her 1818 version of Frankenstein.19 This unfortunate reality of the time means Shelley would have been aware that female involvement in a work—as an author or as characters—could diminish the book’s reception, thereby reducing her opportunity to make a point about the treatment of women in society. Her later work, published after Shelley achieved financial independence from her husband, was “highly political.”20 Considering this context, it appears Shelley wanted to make a statement with her female characters but knew doing so would damage the book’s credibility, so she chose instead to make a statement with their absence.

In short, while Frankenstein does, of course, show scientific experimentation devolved into calamity, the cautionary aspect of this tale lies in the human interactions. As both a member of an elite family and an educated scientist, Victor manifest the privileged class who make decisions regarding the lives of others. Responsible for the creation of the outsider, Victor then treats that outsider with disdain, a choice which eventually leads to Victor’s downfall. Hidden inside this narrative is a commentary on a specific class of outsider: women. If Victor portrays the privileged class in society, then his mother is the feminine influence that goes unheard. Shelley’s warning here is significant: viewing the outsider as a monster and ignoring the voices of society’s unseen members can prove disastrous.

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 21. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 27. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 54. ↵

- Lars Lunsford, “The Devaluing of Life in Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN,” Explicator 68, no. 3 (2010): 174. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 51. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 51. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 51. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 88, 91. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 91. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 131. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 148. ↵

- Anne Mellor, Mary Shelley (New York: Methuen, Inc., 1988), 129. ↵

- Anne Mellor, Mary Shelley (New York: Methuen, Inc., 1988), 130. ↵

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003), 188. ↵

- Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler, The Monsters: Mary Shelley and the Curse of Frankenstein (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2006), 186. ↵

- Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler, The Monsters: Mary Shelley and the Curse of Frankenstein (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2006), 186. ↵

- Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760-1850, December 2003, s.v. “Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus 1818,” by Peter Otto. ↵

- Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760-1850, December 2003, s.v. “Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus 1818,” by Peter Otto. ↵

- Bernard Duyfhuizen, “Periphrastic Naming in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein,” Studies In The Novel 27, no. 4 (1995): 477. ↵

- Continuum Encyclopedia of British Literature, April 2003, s.v. “Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft,” by Nora Crook. ↵

122 comments

Megan Copeland

Last year, my class read Marry Shelley’s book Frankenstein. I had never read it before and only knew that it had something to do with a monster. The book was so much more complex than I ever though it would be. I think you made a very good point on how the book had an underlying theme of how people treat one another. I think this article was very well written and researched. I also think the pictures played a big role in what made this article so good.

Irene Astran

I read this novel in high school and did not think much of the lack of female presence. I reread this novel in my Junior year and it was finally brought to my attention that she made this statement. This was a smart move in that she probably would not have been published. She spoke volumes through that silence and challenged us to read in between the lines.

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. I have never read Frankenstein, but the author did a great job explaining the overall novel. I feel like the message that Shelly was trying to convey is so important in the political and societal climate of today. So many people today fear the poor and the struggling because they view them as outsiders, just like the doctor in the film. alienating them or judging them based solely on their appearance is such a huge mistake, and it is one that is being made today

Daniela Cardona

I have been told to read Frankenstein for and english class more than once, so a lot of this was already known to me. Yet, the article was still well polished and intriguing. The writer used very good analytical skills and he explained things that many people tend not even realize when they read Frankenstein. The book is about so much more than a mad scientist creating life in the form of a ‘creature.’ When you read critically, Frankenstein is the story of a time, of society and of human interaction.

Jennifer Salas

I now see Frankenstein with a whole different perspective and I never knew much about the story other than the basics. It was really interesting and helpful when the author provided examples. Although I wish there could have been more female characters I really want to read this story.

Ximena Mondragon

This article is very interesting because I am actually reading Frankenstein in my literature class, and it’s an amazing novel. When Frankenstein was first released people thought that Shelley’s husband had written it but it was actually her. Overall, the author does a great job at analyzing the novel in an article and the arguments about it. I think more than ever her novel is impactful because scientist are now cloning animals and then humans. Her novel could also serve as a warning to those seeking knowledge beyond the laws of nature.

Tessa Bodukoglu

this was a very interesting article. I’ve always heard of the stories of Frankenstein, but I have never actually known what the real story was. I find it very interesting that the monster was built from scratch, and then later in the story, the monster just wants someone else to love him and to share his company with him. but overall, this was a very interesting read and I really enjoyed reading this.

Micaela Cruz

This article was extremely interesting to me, and why I say that is because the author dived deeper into the story of Frankenstein and revealed much more than what was on the surface. I read the story of Frankenstein during my sophomore year of high school and I did not realize the significant impact of the absence of women in the story. The analysis of the story provides a different perspective of the main protagonist, Victor, and how he was a bit of a selfish character towards his creation. Great article.

Ysenia Rodriguez

This article was amazing. It was well written, well prepared, and overall very interesting and insightful. You looked further than the simple plot and text of the novel and really dug deep into the subtle details (and lack thereof) to highlight reasoning for certain important moments in the text. I have not had the opportunity to read Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein-or even see a single movie about this character- but I would love to check out a copy of this novel as soon as I can.

Dylan Coons

A very interesting article about Mary Shelley and the masterpiece known as Frankenstein. I think this article does a great job explaining the role of the outsider and the different themes of this story, which includes several things that I think most people overlook when analyzing the book. I also agree with the author when it came time to discuss others who criticize the book for lack of female roles within the book.