The Golden Age of Piracy was a chaotic mess, involving heightened criminal activity in the ocean.1 Jailbirds, slaves, and women (in disguise) alike were given the ability to sail freely alongside their captains as any typical white naval officer would, even gaining their own small ships for themselves or important roles.2 Granted, life wasn’t easy for a babe born to an incarcerated mother, or an adulteress, like Anne Bonny. Later, an impoverished sailor on his special day vowed to this woman to be with her forevermore. Anne Bonny vowed her side of the ceremony. That same sailor was denied any fortune from her family because of her decision to marry so impulsively. Due to poverty thereafter, the man was forced to the Island of Providence—the pirate hotspot—for a job with which to fill his pockets. But it was rather boring being the dame, waiting around for success to take hold for her groom. In the very bar where she waited, a rugged fellow came in.

The seadog wasn’t too handsome. He smelled of booze, and his breeches were dirty and well-worn with debris and blood: calico under such grime. He chose wisely which dame he was to conquer. Anne, a lady of red locks and pale skin, already taken by oath in marriage, ignored this commitment and readily seduced such a hungry man. But there was something about him, this calico-trousered brute: he was smitten. So smitten, in fact, he poured out his pockets like a gambler on a winning streak. He had so many stories, so many jewels and treasures. This lass caught a glimpse of the great blue goliath—the sea—that lay in the ravines of the cracked earth as she was delivered to the colonies back in the early 1700s when she came as an immigrant child.3 It was almost natural to be near the sea.

On and on, the calico-covered man recited the same words. He suggested, maybe…just maybe, he could bribe, better yet, pay for the dame to travel far and wide with him. Any other lady would’ve taken considerable time in thought about the decision. After all, the pirate life was one of a fly: short and brutal with the constant threat of death. For one, Anne Bonny was a bonny lass who wasn’t afraid of death. So, she agreed.4

A fair warning to the audacious in spirit: such an agreement to venture forth into unknown territory with a pirate would receive punishment. Bonny became a mirror image of her mother, an adulteress. She was threatened by the abuse of whips by government officials after a quick confession of betraying the man she called “husband.” But what of the calico-covered man? His name was John “Calico Jack” Rackham. With great conviction, she was to board the ship with him, and much later, another would as well.5

“Aye…where do we begin?”

Quick Note:

Captain Charles Johnson, also possibly known as Daniel Dafoe in other copies of A General History of Pyrates, was responsible for the majority of Pirate lore and history. He self-proclaimed himself as a “faithful historian.”6 His work was written in the mid-1700s and wholeheartedly understood the critiques of those who read and thought that his works were dramatized about real people. Many researchers, historians, students, or fans of pirate literature can all pinpoint a large number of records written by him, and the two women in this article are mostly neglected throughout the mention of popular pirates.

Anne Bonny’s life started in a prison, born to a servant woman named Mary Brennan from a secret affair, often made to wear male clothes under the identity of a “Relation’s Child [her father] was to breed up to be his Clerk.”7 This happened in Cork, Ireland. The exact location is unknown, and her birth was estimated around 1698.8

Her half-siblings (2) died, so her existence remained the only one in her father’s life.9 Her maiden name was Cormac and she was indeed a bastard. She left to America and landed in Charles Towne, South Carolina, in her early years as a babe.10

171811

In her teens, she met with a retired sailor in Charles Towne, named James Bonny, and married him behind her father’s back, when her father had just thought of finding an appropriate spouse for her to receive “good Fortune,” and it angered her father greatly.12 So much so, her father kicked her out of the house, but she gladly followed her husband to the Island of Providence where he could find a job and support themselves.13

It wouldn’t matter for long, though, because in her boredom, she had exchanged intimate whispers with Rackham and was convinced to leave Mr. Bonny for a life of constant running, excitement, and money with her new pirate lover under the alias “Bonn.”14 She was “threatened with flogging” as punishment in a trial before Rackham had paid her ransom to convince James Bonny for the woman’s freedom to elope.15

She was in love with her Captain. Naturally, such intimate moments on a ship for several days at a time, being a young woman with impulsive desires, caused a pregnancy to emerge between her and her pirate lover. And hearing this, Rackham sent her away to Cuba to “Friends of his”—trustworthy, one would hope—and she delivered the babe there on the island. Debates on whether the babe lived, died, or was given to another mother to raise are muddy, but nonetheless, the babe was delivered.16

August 1720

Her health was restored. As soon as Rackham heard of her recovery, he came for her. During this time, the proclamation of the Governor of Jamaica was announced and she went with Rackham during his compliance to the surrender, benefitted slightly by her father’s fame, but her decision to drop her original husband was looked down upon. The peace of landlubber life would once again wear off from Anne’s perspective.17

But when she returned to piracy aboard the Revenge, she and the crew captured a Dutch trading vessel, adding more people to the crew count, including a handsome young stranger. One way or another, “for reasons best known to herself,” she had pushed her desires to know this young fellow: in return, the man confessed to her that he could not be intimate and revealed himself as a woman in the disguise of men’s clothes.18

This disguised woman would reveal herself by the name of Mary Read.

“No Boy or Woman to be allowed among them.”25

Unlike Mary, though, Anne didn’t disguise herself, but their friendship was firmly developed.26 So one would imagine what conversations would spark from an interaction such as this with the subject being so familiar to them both. It became evident of their bonding and deep connection to the point where Rackham became so intoxicated with jealousy, he threatened to get rid of Read rather violently. This would only subside from Mary revealing to him her secret of being a woman. His rather hasty behavior was tamed soon after.27

Fierce Stories

Anne Bonny was considered “of a fierce and couragious Temper” and a possibly apocryphal set of stories explains just how passionate she was. One of which involved intense violence and a knife against her father’s house servant. The other involved an attempted rape in which “she beat him so, that he lay ill of it a considerable Time.”28

She was noted by Charles Johnson that “[i]n all these Expeditions, Anne Bonny bore [Rackham] Company, and when any Business was to be done in their Way, no Body was more forward or couragious than she…” 29

Johnson suggests a story, which may or may not be accurate, but nonetheless provides consistency for Mary’s character, as she provided evidence many a time where her infatuations for a military fellow overthrew her focus. She was of “Cunning and Reserve,” and, “Love found her out in this Disguise, and hinder’d her from forgetting her Sex.”30

When the crew of the Revenge captured a ship, one young man stood out to her, fueling her passion to be near him, and again, another friendship ended with a revealing of her true identity. Long story short, their interactions led to an exposal of information revolving this young man and a duel which was supposed to take place offshore—as in pirate tradition—and she took the responsibility of the duel to ensure his safety and to protect his refusal to the challenge not to be recognized as a coward.31

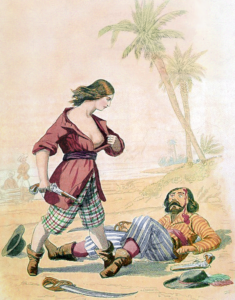

Out of noble romance, she “fear’d more for his Life than she did for her own…”32 Having said that, she met the man who challenged her lover, Tom Deane, and “she appointed the Time two Hours sooner than that when he was to meet her Lover, where she fought him at Sword and Pistol, and killed him upon the Spot.”33 This would be the source of the modern belief of women pirates showing their breasts before their victims to further embarrass their loss.34

The two women were noted by future testimonies of their appearance off the ship in which they commented that the women often adorned themselves in masculine fashion and handkerchiefs (or bandanas) on their heads: not without any weapons, of course.35 They also said:

“[They w]ere both very profligate, cursing, and swearing much, and very ready and willing to do any Thing on board.”36

“[They] did not seem to be kept, or detain’d by Force…of their own Free-Will and Consent.”37

September 1720

They had captured a woman by the name of Dorothy Thomas in a canoe. She was held as a prisoner on the Revenge, being irrationally pinned in a corner by Bonny and Read, and for many moments, the two pirates harassed with the crew violent language into taking precautionary measures, threatening to get rid of her. No one did.38

October 172039

There was an order commissioned against the pirates. Captain Johnathan Barnett gave chase in the distance aboard his vessel, the Tygre. Anne Bonny and her companions were on a time limit.40 Like the beast it was named after, the vessel lurked near port cities where Pirate activity was most notable.

November 172041

The crew had captured a few more ships, usually smaller vessels like fishing boats.42 They were in the humid, damp, and disease-infested waters of the Caribbean, where storms remain violent and cruel to the wooden trims of ships, snapping the beams of the sails with a delicate touch, and such violence only occurs outside of gunfire. The seas know no peace.

Rackham was already wary about the new naval order, and one could imagine his leading ladies were also rather vigilant about the situation. Upon reasons of celebration for the prior catches, Rackham had drank with the crew and then the terror came in the form of gunfire and a sloop. In cowardice, they ran below the deck to hide.43

Charles Johnson says:

“[P]articularly at the Time they were attack’d and taken, when they came to close Quarters, none kept the Deck except Mary Read and Anne Bonny, and one more.”44

Then again:

“[Anne Bonny] and Mary Read, with one more, were all the Persons that durst keep the Deck, as has been before hinted.”45

Appalled, Mary called to the crew and demanded their compliance to defending the ship, and when they refused from cowardice, she impulsively came down with a pistol, and well, what happened was much more than intimidation. Several were wounded and one was lost.46 From there, the three defended as best they could until Barnett had captured the crew.

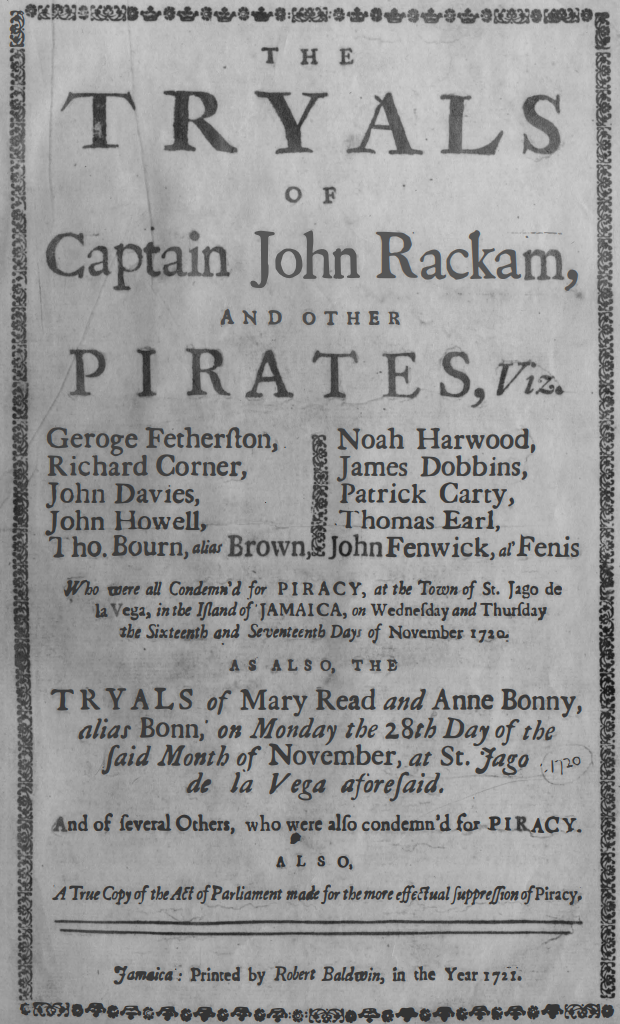

November 16, 172047

Rackham, after begging, had the opportunity to meet with his lover one more time before his execution.48 Oh, how exciting! A moment of reconciliation and utter emotion in an exchange between two people! What would his lover say on his final day? ‘I love you’? ‘I can’t live without you?’

She said, “[I’m] sorry to see [you here], but if [you] had fought like a Man, [you] need not have been hang’d like a Dog.”49

Wait, what? He was dragged away to be shown on the gallows of the port as a warning to sailors from then on.50

November 28, 172051

In the women’s trials, they were met with a familiar face: a washerwoman. 52

Dorothy Thomas was called to the stand, and she, predictably, explained how she was threatened to be killed by two belligerent women. She knew they were women by the “largeness of their Breasts.”53

The court referred several times back to Mary’s outbursts of passion, especially due to the witness account. And no matter how the question was asked to her about her outburst before the capture, she denied and denied again such violence.54

Despite how much evidence gathered against them, Mary Read of the two was also recorded to be strongly against piracy, only turning to it due to circumstance and necessity.55

Mary Read was of such noble character, she confessed her lover was “her Husband, as she call’d him,” never exposing his identity and was deemed a subject of great sympathy, though, the charges were largely against her.56 She also stated, when asked about her beliefs (largely incited by a curious Rackham beforehand):

“[…T]hat as to hanging, [I] thought it no great Hardship, for, were it not for that, every cowardly Fellow would turn Pyrate, and so infest the Seas, that Men of Courage must starve:— That if it was put to the Choice of the Pyrates, they would not have the punishment less than Death, the Fear of which, kept some dastardly Rogues honest; that many of those who are now cheating the Widows and Orphans, and oppressing their poor Neighbours, who have no Money to obtain Justice, would then rob at Sea, and the Ocean would be crowded with Rogues, like the Land, and no Merchant would venture out; so that the Trade, in a little Time, would not be worth following.“57

The jury ultimately decided: guilty.58

Wait, wait, wait!

They pleaded their bellies to the court, and a doctor was appointed to check if these things were true. Two women, already shocking to the court, were spared by the ideal timing of their wombs. 59

Mary Read had died of a fever during labor in the prison, but Anne Bonny disappeared from the scene. On April 28, 1721, Mary and her child were put to rest underground in Jamaica. 60

Anne Bonny, on the other hand, was claimed to be pardoned time and time again, and many suggest theories that she was taken in by men of her past.61 Oxford records suggest that she had more children after being delivered from prison as evidenced through descendants, possibly dying on April 25, 1782.62

But Johnson ends his commentary simply:

“[O]nly this we know, that [Anne Bonny] was not executed.“63

- Mark Cartwright, “Golden Age of Piracy,” World History Encyclopedia, October 12, 2021, https://www.worldhistory.org/Golden_Age_of_Piracy/. ↵

- Colin Woodard, The Republic Of Pirates: Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down (HarperCollins, 2008), 3. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 249. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 165. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 157, 172. ↵

- Marcus Rediker, “When Women Pirates Sailed the Seas.,” Wilson Quarterly 17, no. 4 (September 1, 1993): 102; Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 165. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 170-171; Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 249. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 249; David Cordingly, Seafaring Women: Adventures of Pirate Queens, Female Stowaways, and Sailors’ Wives (Random House Publishing Group, 2002), 81. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 165-171. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 249. ↵

- David Cordingly, Seafaring Women: Adventures of Pirate Queens, Female Stowaways, and Sailors’ Wives (Random House Publishing Group, 2002), 65-87. ↵

- Sally Driscoll, “Anne Bonny,” Anne Bonny, August 1, 2017; Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 172; Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 249. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 172. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 157, 172. ↵

- Sally Driscoll, “Anne Bonny,” Anne Bonny, August 1, 2017. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 172; Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 251. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 172. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 252; Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 162. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 252. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 157-158. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 158-159. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 161. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 161. ↵

- Marcus Rediker, “When Women Pirates Sailed the Seas,” Wilson Quarterly 17, no. 4 (September 1, 1993): 102. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 231. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 251. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 162. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 171. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 172. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 162. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 163. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 163. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 163-164. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 252-253. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 252. ↵

- Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. (Random House Publishing Group, 2013), 64. ↵

- Marcus Rediker, “When Women Pirates Sailed the Seas.,” Wilson Quarterly 17, no. 4 (September 1, 1993): 102. ↵

- Marcus Rediker, “When Women Pirates Sailed the Seas.,” Wilson Quarterly 17, no. 4 (September 1, 1993): 102. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 253. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 155. ↵

- Mark Cartwright, “Anne Bonny,” World History Encyclopedia, accessed February 18, 2023, https://www.worldhistory.org/Anne_Bonny/. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 152. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 155. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 160. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 173. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 161-162. ↵

- Sally Driscoll, “Anne Bonny,” Anne Bonny, August 1, 2017. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 173. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 173. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 156. ↵

- Sally Driscoll, “Anne Bonny,” Anne Bonny, August 1, 2017. ↵

- Marcus Rediker, “When Women Pirates Sailed the Seas.,” Wilson Quarterly 17, no. 4 (September 1, 1993): 102. ↵

- Marcus Rediker, “When Women Pirates Sailed the Seas.,” Wilson Quarterly 17, no. 4 (September 1, 1993): 102. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 162. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 161. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 164. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 165. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 156. ↵

- David Cordingly, Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates (Random House Publishing Group, 2013), 65. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 165; Sally Driscoll, “Anne Bonny,” Anne Bonny, August 1, 2017. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 173; Sally Driscoll, “Anne Bonny,” Anne Bonny, August 1, 2017. ↵

- Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History’s Most Notorious Women (Penguin, 2011), 254. ↵

- Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates (Dent, 1972), 173. ↵

27 comments

Sudura Zakir

The way you organized this article and the manner this narrative was told were both excellent. I often forget that pirates actually existed and that women would find methods to join them when I study their history. I think it’s brave that these two ladies, even if it did mean being pirates, took charge of their lives and futures. They experienced some freedom and adventure as a result. Thank you for sharing this amusing anecdote, and congrats.

Aaron Astudillo

Congratulations on the nomination and being able to find such information on a topic that many may not often think of. The history of piracy is often interesting, but it is taken a step further when you consider the role that women had on this age. Thus, the adventure of pirates is a great topic and even more interesting read.

Karicia Gallegos

Congratulations on your nomination! I had no prior knowledge of this until I read your article. I thought this article was really fascinating and instructive. It was a fantastic story about Anne, and I thought the writing was excellent. There was a lesson to be learned in the narrative, despite the fact that it didn’t have a particularly nice ending. I found your article to be very interesting. Overall, great job!

Maximillian Morise

A fascinating article on the Golden Age of Piracy and the role of women within it, with great images and remarkable research used throughout it. Congratulations on your nomination, as this is a very worthwhile and well-researched historical article on this topic!

Kristen Leary

This was a very interesting topic for an article that I don’t think I’ve ever thought about. Admittedly, I don’t know much about pirates, but I have certainly heard very little about women pirates. It was definitely an interesting read and I’m impressed by the amount of research that must have gone into this.

Noelia Torres Guillen

This story was well told, I really liked the way you organized this article. When I learn history about pirates, I forget that hey actually existed and that women would find ways to become pirates. I think that it’s brave for both these women took control of their life and future, even if it did mean being pirates. It gave them a sort of adventure and freedom. This was an entertaining story and congratulations on your nomination.

Abbey Stiffler

The introduction does a great job of drawing the reader in; it piqued my interest in this clever woman. Despite having different histories, they ended up in the same location and were forced to dress like men. It’s amazing to learn how women supplied positions that are typically associated with men. It is disappointing to find that the story still heavily emphasizes their sexuality.

Luke Rodriguez

This was a fantastic read! Also, congrats on the nomination! It was well-deserved. The article was well-written and detailed. This was a well-structured article, and I truly enjoyed reading this. Their backgrounds were different, but they both were in the same situation, disguised as men. They were daring individuals who relished the thrill of living the pirate life on the high seas amidst a tumultuous, unclean, and dangerous era of history.

Barbara Ortiz

Congratulations on your nomination for such a great article, Anayetzin. I love that you were able to find all this information on female pirates! You also provided a well written article and I like the timeline of events you provided as well. These are the kind of stories I hope to still be able to use in my teachings when I get my teaching certification for history.

D'vaughn Duran

Congratulations on being nominative! This article is very well sourced with great information. It is well structured and I enjoyed reading this article. I liked how you put the dates because it added more notification of the piece. This was a very interesting topic I didn’t know much about! This information was very engrossing with women pirates with their trial.