On April 5, 1870, at just thirty-two-years old, Victoria Woodhull announced her run for president of the United States. During the election of 1872, neither party, Democrat or Republican, had any significant issues to debate. Slavery had just been abolished in 1865, which had been a significant goal of the Republican Party. So what was left to discuss? At the time, the women’s suffrage movement was at a crossroads of whether to continue its efforts with strategy or action, or perhaps a mix of both. Victoria Woodhull determined that moving forward with action for women’s suffrage was the best method for achieving the results she wanted. She decided that because the political climate had calmed a bit, it would be the perfect time to announce her run for president. She published a letter of announcement in The New York Herald, which brought attention to the fact that no significant issues were voiced during the election. So, she produced one, “whether women shall…be elevated to all the political rights enjoyed by man. The simple issue is whether women should not have this complete political equality.”1 Woodhull’s run for president held up a crucial precedent set by Elizabeth Cady Stanton just four years before when she ran for Congress. The ability of women to run for government positions while being unable to vote displayed the paradoxical laws set around women’s suffrage in the United States.2

White American women were citizens in the 1800s, but were never given the full rights of their male counterparts. However, that doesn’t mean progress wasn’t being made. In 1860, Susan B. Anthony pioneered New York’s Married Women’s Property Law. This law gave women the right to their property, wages, and children. Furthermore, the property they acquire would remain theirs if they were to marry.3 Gaining control over the very children they created was a fantastic win for women, but they wanted the biggest authority setting them apart from men: suffrage. Women across America had worked tirelessly for decades to bring attention to the discrimination holding them back from their full citizenship. Thankfully, women like Victoria Woodhull were around with extreme ways to draw attention to the matter.

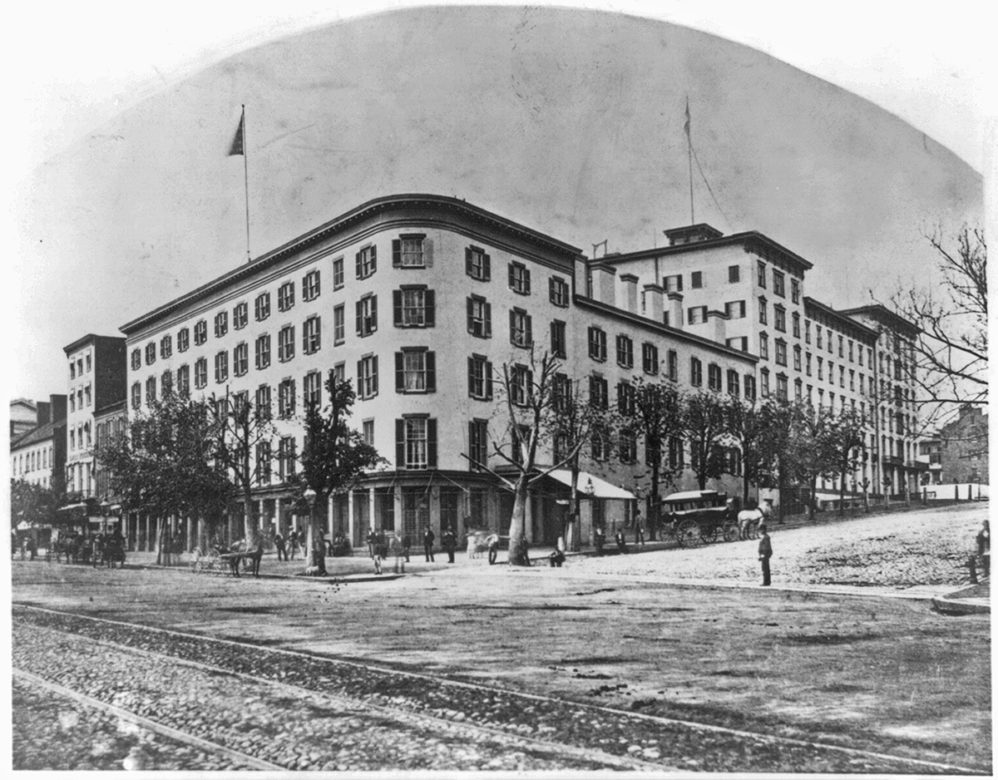

Woodhull knew that if she wanted to make any progress at all, she would need to get into the heart where change happens in the United States. So, in the fall of 1870, she made her way to the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. The Willard Hotel would become her base camp to enact her main plan of procuring the sixteenth amendment. The Willard Hotel was known as a hub for members of Congress, senators, and lobbyists to discuss issues and make deals. She initially intended to go to Washington to get the ball rolling for women’s suffrage, but soon found out that wasn’t going to be possible during her time in DC. During Woodhull’s conversations in the Willard Hotel, she was informed that leaders of the opposing sides for women’s suffrage would naturally bicker to no end. Many Democrats urged her to fight for her own presidency instead of worrying about the 16th Amendment. Woodhull was stubborn and didn’t want to abandon her intentions because of hearsay. What really led her to hear the truth was her relationship with General Benjamin Butler. Butler was a close associate of President Grant, and he greatly benefited from the spoils system. She learned from Butler’s insider knowledge that the 16th Amendment was at an indefinite standstill.4

Before going back to New York on January 1, 1871, Woodhull’s work with Butler had become well known and created a new momentum in the suffrage movement. She accepted that the 16th Amendment wouldn’t get much attention, so she changed her efforts. She argued her interpretation of the 14th Amendment, which had never made any exclusions based on sex. Her publications of this interpretation had even led the author of the 14th amendment, John A. Bingham, to question the power of his language. With Butlers’ help, Woodhull urged a petition for Congress to enforce the 14th amendment under her interpretation, which would allow women to vote. With the help of Butler’s connections in Congress, she obtained the right to present herself to the House Judiciary Committee. Her presentation occurred at the same time as the Women’s Convention in January.5 On January 11, 1871, Victoria Woodhull entered the committee room, becoming the first woman ever to address a congressional committee. Woodhull presented alone, but she certainly didn’t lack support. Her lover and mentor, Benjamin Butler, her sister Tennesse “Tennie” Woodhull, and multiple women in support, like Susan B. Anthony, were all there to stand, or rather sit, in solidarity. Woodhull struggled at the beginning of her speech. She had published articles and lobbied for years, but this was her first time publicly addressing a group. She clearly expressed the fallacies of the 14th Amendment in conjunction with the Constitution. Woodhull’s speech was so powerful that the New York Herald wrote, “Other speeches were made, but Woodhull had captured the committee and, the others were not needed.”6 The feeling of all the women attending the convention after Woodhull’s presentation had never been felt before by women in politics. Women had been lobbying for rights for decades, wives of politicians quietly whispering for women’s suffrage. Now, it had been done! Victoria Woodhull took the stand in a congressional Committee creating a fierce presence of women in American politics.7

During Woodhull’s time in the White House, she was able to speak with the president himself, Ulysses S. Grant. President Grant agreed that women’s suffrage was a worthy cause. She was indistinct about her conversation with the President; she was confident about stating “The President is with us [women’s suffrage leaders].”8 Unfortunately, President Grant’s support would never manifest into something tangible for women’s suffrage. So, Woodhull published her opinion of Grant’s administration in her paper. Essentially, she said that he [President Grant] was surrounded by weak men, which resulted in his weakness and that would be his ruin.9

Woodhull’s time spent in Washington and the conversations she had left her only more resentful of the Democratic and Republican Parties. Washington’s impression spurred her formation of the Cosmo-Political Party. Woodhull announced this new party along with her nomination for the presidency in the Weekly. This political party would not fight for the 16th Amendment; rather, it declared that voting was an inalienable right of all citizens, no matter whether male or female. She opened her campaign for President by renting out Lincoln Hall for a public address. The plain fact that Woodhull could afford to rent such an extravagant hall won the respect of many other suffrage leaders that had previously seen her as incompetent. Those same suffragettes appreciated her passion for the movement. Reporters that gathered to cover the event noted that Lincoln Hall had never seen a larger audience before. The mass that flocked to see her filled the auditorium quickly and people had to begin searching for other seating arrangments. Paulina Wright Davis, a fellow suffrage leader, introduced Victoria Woodhull, and then she began her address. Woodhull spoke about her time in Congress and about a conversation she had with John A. Bingham, which was very telling for how women were treated at the time:

“When I was before Congress I said to Mr. Bingham, ‘I want to vote because I am a citizen.’ He replied ‘You are not a citizen.’ ‘What am I?’ I asked. ‘You are a woman’ he said. 10

Woodhull went on to captivate her audience for an hour and fifteen minutes. She explained her lines of reasoning, compared women’s rights to freedmen’s rights, and voiced her concerns about taxation without representation. When she closed, there was a consensus among the audience that she had been effective in opening her campaign and delivered an exceptional speech. Just shortly after, she delivered a message in New York, where she yet again received applause and praise for her poise and ability to enchant an audience.11

Woodhull was only at the beginning of her campaign and had much more to do in the months following her Lincoln Hall address. She delivered her famous Succession Speech on May 11, 1871. During this speech, she once again charmed her audience with her intellect. Being well-educated and informed was noticed by her listeners and by the reporters that would post about her. Her credibility was growing and so was her popularity. Gaining support is a presidential candidate’s number one goal, and Victoria Woodhull was quite good at it. For her events, like the Succession speech, she was diligent about providing complimentary tickets to suffrage leaders whom she intended on winning over. These traits are all so fitting for a presidential candidate: tenacity, ambition, and charisma; but, she had the tendency to be radical. This extremity is exhibited in her Great Succession Speech, where Woodhull declares that if women aren’t given the vote, they [suffragists] would start their own government. Woodhull’s approach to suffrage caused a divide in the movement. Many suffrage leaders went all in on backing her. Some may have argued that their support was based purely on an emotional high from her lectures. But others, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, were cautious and hesitated to fully back Woodhull. This caution caused many reformers to take a backseat to the idea of Woodhull running for president. These doubts, however, did not slow her down. Woodhull designed her presidential uniform, flaunting it to the press, and she even practiced her signature for autographs. Her inflated sense of confidence, paired with her incredible speaking skills, kept her campaign afloat.12

Woodhull was able to maintain a fierce campaign, but her brokerage was being neglected. Most of the brokerage’s deals were more of a gamble than an investment, and paired with her sister’s lack of fiscal responsibility, the firm began to go under. So, Woodhull’s brilliant plan was to start writing papers exposing other bankers who were using their insider knowledge. She figured the paper sales would sustain them more than the brokerage profits. The muckraking was able to sustain her just until around March of the following year. Unfortunately, right around that time, Woodhull’s promised donations to the suffrage movement stopped coming through; she had to downsize and was unable to throw the extravagant parties she had at first.13 Desperate to secure her name on the ballot, empty promises began pouring out. She gave an estimation of funding that would be obtained, based really just on wishful thinking. She continued to fumble her campaign as it got closer to nomination time. Her ultimate mistake was made out of hopelessness when she made, yet another, persuasive speech to be the nominee for the Equal Rights Party. Woodhull had to abandon her own creation of a political party, as it hadn’t developed any support. She was convincing enough to get her name on the Equal Rights Party ballot, with Frederick Douglas as her running mate. Interestingly enough, Douglas had no idea about his name on the ballot. It may have been a good idea to quit while she was ahead, but she persevered. She was going broke and her past endorsers slowly began to resent her for her outlandish behavior.14

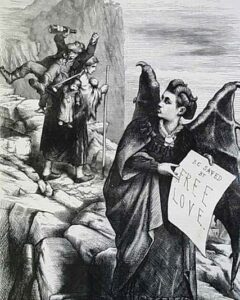

Just months before the election, Woodhull was called to court for not paying her debts. She was living in her office, sleeping on borrowed furniture. The humiliation of being penniless put a damper on her intentions to be president, and slowly her public image started to fade from relevant political news. In a last-ditch effort, she began writing a paper again, and got herself into a scandal when she made remarks about a local scandal. Woodhull’s opinions were torn apart in an interview, and that sent her into a spiral of questioning the construct of marriage and endorsing sexual experimentation. Because the scandal she commented on was within the realm of marital affairs, it caused outrage among those who viewed those topics as immoral and threatening to the youth. A concerned citizen obtained a warrant for the arrest of Victoria Woodhull and colleagues. So, on November 2, 1872, Woodhull was arrested by US marshals along with her sister. They were charged with sending obscene literature by mail, among various other crimes, and sentenced to appear in Federal court the following Monday, November 4. The sisters were released from the court that same day, but were immediately rearrested for other indictments. The sisters spent the night in jail and woke up on November 5, election day. It was then, in cell 11 of Ludlow Street Jail, that Victoria Woodhull was informed of President Ulysses S. Grant’s reelection.15

Finally, the sisters were released from jail on December 5, thanks to some wealthy sympathizers. Woodhull’s first order of business was to make a public address in her paper, only to find it had been banned. Woodhull never addressed the fall of her campaign; rather, she shifted her aim and continued with speeches concerning confidence and sexual debauchery, among various other seemingly random topics.16 Her speeches were short-lived as she soon fell ill of reported chest pains and barely survived. Though she survived, many say her spirit didn’t, and Woodhull wasn’t ever the same after her recovery.17 In 1877, Woodhull moved to England. She began a new life and did her best to hide any evidence of her scandals. She was simple and much different than the Victoria Woodhull that the suffrage movement in the United States had come to know so well.18

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 78. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 77-79. ↵

- “Antebellum Women’s Rights | American Experience | PBS,” Public Broadcasting Service, accessed March 20, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/lincolns-womens-rights/. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 94-97. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 99-101. ↵

- Mary Gabriel, Notorious Victoria: The Life of Victoria Woodhull, Uncensored, First (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books, 1955). 77 ↵

- Mary Gabriel, Notorious Victoria: The Life of Victoria Woodhull, Uncensored, First (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books, 1955), 73-78. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 105. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 106. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 111. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 110-115. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 1935), 117-127. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 128-131. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 209-213. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 228-232. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 235. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 250. ↵

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran For President, First (Bridgehampton, New York: Bridge Works Publishing Company, 277. ↵

13 comments

Lauren Sahadi

This article was great. I had no idea about this woman. It’s great that you highlighted an important part of history that I’m sure not a lot of people know. The way you told her story was amazing. It’s inspiring for women. Victoria was very courageous for running for president in a time when women weren’t seen as equals. Very powerful article.

Daniel Gutierrez

I am in complete udder shock! I can’t believe I was uninformed about such a historic and pronounced character Victoria Woodhull stands now as such an existence that changes the narrative of what can be done in so many peoples mind. Hearing of the great achievements that she has done and now the fact that she is still being talked and that this article does such a great job in doing that helps her character reach so many more people

Andrew Ponce

Hey Alexandra! This is an amazing article. It’s amazing to see stories based around historical heroes that not many people know about. This article covers the story of such an influential figure that impacted not only women, but the surrounding community of people all around. This article serves as an inspiring message to those who want to make an impact on the community around them. In the article, Victoria, courage serves as a powerful reminder for women and people in general to continue to fight for what they believe in. Amazing Article!

Sudura Zakir

This tale is so motivating! I’m very glad you published about this remarkable woman. We discussed a lot about her in my gender politics class, which I’m now enrolled in. She took a position for women’s rights despite the commotion it caused, but she succeeded in proving her point. Because modern women can read her narrative and learn not to be scared of the difficulties brought on by men, it is now motivational. Great writing and a fantastic article. Well done!

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

Love how this highlights the challenges and prejudices faced by women in the political arena and sheds light on the courage and determination of women like Victoria Woodhull. The article is well-written, informative, and encourages readers to reflect on the progress made towards gender equality in politics and the work still to be done. Very inspiring!

Bijou Davant

Honestly, this is a story I was so unfortunately unaware of! It is really interesting to me to see Victoria run for president, especially knowing women weren’t even granted suffrage for another 50 years! I really think people feel threatened by powerful and intelligent women!

Alexis Zepeda

Hello Alexandra! This is a great informational article. It is common for most people to only associate Susan B. Anthony with the fight for women’s suffrage, and it is refreshing to hear about other women who have fought for women’s suffrage as well. Prior to reading this article, I did not know about any women who ran for president in the 1800s. Given there has yet to be a female president in the United States, Woodhull’s story has the ability to continue to inspire women.

Maya Naik

Hi Alexandra! I find this story truly inspiring! It’s great to see that you’ve highlighted this remarkable woman. In my current gender politics course, we’ve discussed her extensively. Despite the controversy her actions caused, she stood up for women’s rights and made a powerful statement. Her story is especially motivating because women today can draw strength from it and learn not to be deterred by challenges posed by men. Your article is excellent, and your writing is impressive. Well done!

Juan Aguirre Ramirez

Hey Alexandria, your article was really interesting since it is a very important piece of history that needs to be shared more. It’s great to see historical figures like Victoria Woodhulh, her story is truly inspiring, and it’s encouraging to see how she stood up for women’s rights in a time when it wasn’t widely accepted. Her courage and determination serve as a powerful reminder for women today to continue fighting for equality and not let discrimination or opposition hold them back.

Gaitan Martinez

Yes! I have never heard the story of a woman running for president, and this story was very interesting. Of course, since it was the 19th century, it was obvious she wasn’t going to win because women were not equal yet, they couldn’t even vote at the time! However, we all like an underdog story, and wait until there is a woman president. Victoria Woodhull’s story was inspiring and glad you are trying to get her recognition.