At a quiet New York cemetery in 1959, a handful of people stand around a fresh grave as a casket is lowered. Any passerby seeing the small somber ceremony might assume that the body belonged to a person of little significance. In fact, this casket carries the body of a man who is responsible for one of the largest shifts in international law in human history. Without his efforts, it is likely that the gravest crime mankind has ever committed and continues to commit would still be a crime without a name.

By the end of World War II, the Nazi regime had orchestrated the murder of over 17 million civilians in concentration camps throughout Europe. 1 Despite these egregious atrocities, no one at the time referred to the Holocaust as an act of genocide, not because it was not an appropriate descriptor, but because Raphael Lemkin had not yet coined the word and defined the crime for the world. The outcome of his personal crusade to encode ‘Genocide’ in an internationally recognized and binding Convention to which the US would sign on became his legacy (the US signed on decades after his passing).

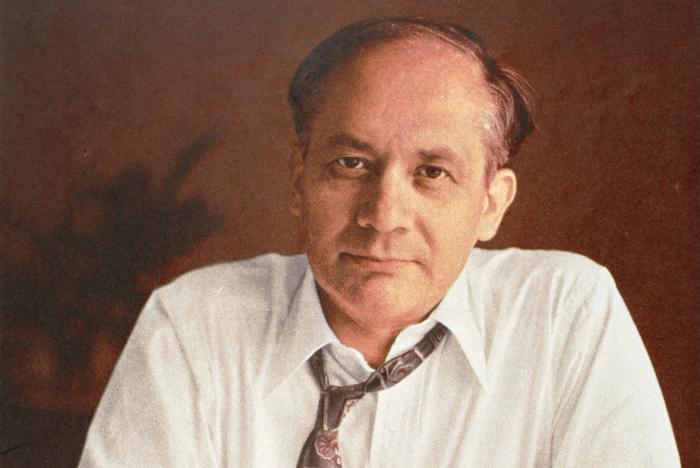

Lemkin was born to a Polish-Jewish family in 1900 in a small village called Bezwodne in what was then The Russian Empire. Home schooled by his mother, he proved to be a brilliant scholar. By the time he received his undergraduate degree from Jan Kazimierz University he had learned over 14 languages and showed strong aptitude and interest in international law. After a career as a prosecutor in Poland, he was forced to flee to Sweden to evade capture by the Nazi forces in 1939. However 49 of his relatives were tortured and/or killed, drops in the ocean of inhumanity that was the Holocaust. 2

After fleeing the Nazi invasion, Lemkin eventually made his way to the United States. There he became a prolific professor, lecturing at the law school at Duke University in 1941 and the School of Military Government at the University of Virginia in 1942. He also served as an adviser to the United States War Department specializing in international law. 3

The world first became aware of Lemkin’s concept of genocide after the publication of what would arguably be his most important work, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, in 1944. Primarily a legal analysis of the behavior of Nazi Germany in occupied territories during World War 2, the book also contained a full definition of the crime Lemkin dubbed “genocide.” 4 After this publication, Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to getting the international community to acknowledge genocide as a crime under international law.

Lemkin drafted a resolution for a treaty which would officially ban genocide under international law. He then took his resolution on the road, presenting it to any nation which would hear him, hoping to garner enough support to endorse a convention on the subject. After years of lobbying the international community, The United States UN delegation agreed to present Lemkin’s resolution to the General Assembly. Dubbed “The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” the resolution was adopted on December 9th, 1948. It would be another 3 years before enough countries signed on the the convention to make it enforceable. Much to Lemkin’s dismay, The United States was not one of the first 20 signatories. 5

Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to lobbying those nations which had not yet signed onto the convention, with the United States being his primary target. He invested every moment of his time and every cent of his modest wealth to landing that particular white whale. He eventually died of a heart attack, impoverished, unemployed, and underappreciated, in 1959. His funeral was a small affair, reportedly only attended by 7 people. 6 Yet, today, the is no Law School, no class that teaches Human Rights, nor any conversation of World War II and any of the subsequent Genocides that does not mention his name. More importantly, the Convention provided some tools to prevent or punish such cases.

The greater legacy of his life’s work would not be realized until several decades after Lemkin’s death. The United States would eventually sign the Genocide Convention, but not until 1988. The international community would eventually convict a man of the crime Lemkin coined, but not until the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1998 which found Jean-Paul Akayesu guilty of the Rwandan genocide. Three years after that, Radislav Krstic was similarly convicted for the murder of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in Yugoslavia. 7 Though he died nearly 40 years too early to see the fruits of his labor truly flourish, we can hope that his soul finds solace in the fact that, thanks to him, these heinous actions have a name and are viewed the world over as being among the worst crimes humanity has ever known. Eradicating the crime of genocide still eludes us but at least accountability is now more widespread around the world. 8

- Donald Niewyk and Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University, 2000), 43. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- Rafael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress, (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Department of International Law, 1944) pg. 79. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Jay Winter, “Prophet Without Honors” The Chronicle, June 3, 2013, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Raphael-Lemkin-a-Prophet/139515 . ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- United Nations, “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” United Nations Treaty Collection, 78:1, 1021 (9 December 1948), New York: United Nations, 1951, 278-311. ↵

196 comments

Ximena Mondragon

Congratulations on your nomination, overall this article is well written and informative. It also keeps the reader engaged and it flows very nicely. The introduction of this article shows how Dr. Lemkin was not well known even though he made such a great contribution to human kind. He named and identified such a terrible crime that now can be prosecuted and the victims can get justice.

Gabriela Murillo Diaz

What an interesting topic. I find it odd that you chose to write about a man who defined just a terrible action. While I find it odd, I also found your writing to be incredibly interesting. Describing this man and his impact by simply giving a word to an action is something I wouldn’t think to research. He did in fact leave a legacy because we use that word to this day and its use has a heavy connotation.

Gabriel Dossey

I think many of us are jealous of your acute ability to put life into paper with your writing. I agree completely with the fact you were nominated for best introduction. I swear to God that I felt I was there. I could see it happening and then you made it mean something. Keep up the good work man. Good luck!

Robert Rees

It’s a tragedy that Lemkin passed away before he could see that his hard work paid off. While he may not have eliminated the act of committing genocide, the fact that we have a way of categorizing this egregious crime and punishing those that carryout it is a legacy anyone should be proud to have. Raphael Lemkin is an international hero that deserves more recognition for his years of service for the global community, and this article is a tremendous first step in doing so. Good work Matt!

Montserrat Moreno Ramirez

I think this is a really engaging reading, it really makes you want to keep reading. I think that what Raphael Lemming did was a great plus for the human history. I never could have guessed how much a single person could contribute. Every time someone speaks abut genocide is a shocking a very sad topic or conversation, but thinking that without this and we wouldn’t have known what it is is just crazy!

Really well-written, congratulations

Nathan Alba

I thought this article was really well written, and wanted to say congratulations on your nomination! Genocide, as we know now, is a horrendous crime that is something only the utmost heinous commit. But it is crazy to think that there was a time where Genocide was not a thing. I also found it tragic that Lemkin did not really live to see the impact he left on the world. Regardless he did much to push humanity in the positive direction.

William Ward

There are a lot of terms and topics that we use/mention on a daily basis, without knowing where it came from. It was very interesting and informative to read about the term “Genocide” and how it came about. It is also inspiring how a man, Lemkin, who experienced genocide first hand, came about making such a great addition to human rights. Great article.

Raymond Nash Munoz III

I think I became so fascinated with this article because I found little correlations between this topic and that of my article. My article has to do with US and it’s horrifying internment of Japanese Americans. Which is what really gets me thinking about how it took the US so long to sign off on Lemkin’s resolution. I think it might’ve been because of the US’s atrocities in their own camps and that maybe they were afraid of being accused with Lemkins newly define word. That’s just one possibility, but above all this article was very well written and congratulations on your nomination!

Lorenzo Rivera

First of all, congratulations on being nominated for an award this semester. This article was both very well written, and extremely informative. You did a fantastic job of captivating the reader and clearly explaining the topic at hand, and it is clear that your research on Raphael Lemkin truly aided your development of this article. It was a really great read, and very enjoyable overall. Good luck!

Crystal Baeza

This article was well written and fascinating to read. I’ve never heard of Raphael Lemkin which is surprising considering all he did for the human race. If only he was able to live to see how his work was appreciated. If it wasn’t for Lemkin I wonder how the world would have been differently. It’s upsetting his motivation was to change how humans were treated due the mistreatment of his own family. This was a great read! I can see why you received a nomination, good work!