At a quiet New York cemetery in 1959, a handful of people stand around a fresh grave as a casket is lowered. Any passerby seeing the small somber ceremony might assume that the body belonged to a person of little significance. In fact, this casket carries the body of a man who is responsible for one of the largest shifts in international law in human history. Without his efforts, it is likely that the gravest crime mankind has ever committed and continues to commit would still be a crime without a name.

By the end of World War II, the Nazi regime had orchestrated the murder of over 17 million civilians in concentration camps throughout Europe. 1 Despite these egregious atrocities, no one at the time referred to the Holocaust as an act of genocide, not because it was not an appropriate descriptor, but because Raphael Lemkin had not yet coined the word and defined the crime for the world. The outcome of his personal crusade to encode ‘Genocide’ in an internationally recognized and binding Convention to which the US would sign on became his legacy (the US signed on decades after his passing).

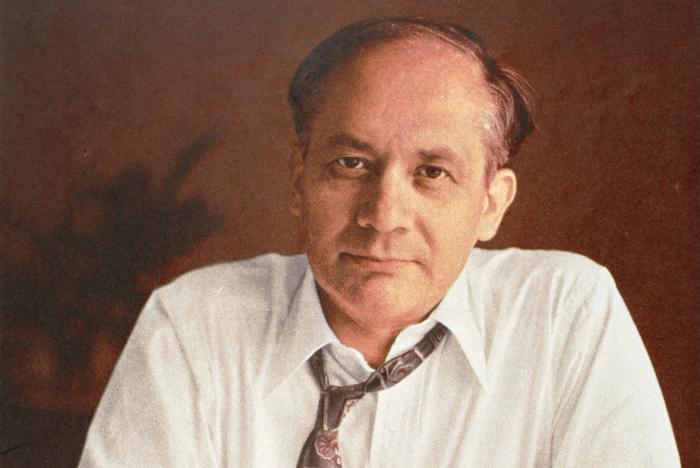

Lemkin was born to a Polish-Jewish family in 1900 in a small village called Bezwodne in what was then The Russian Empire. Home schooled by his mother, he proved to be a brilliant scholar. By the time he received his undergraduate degree from Jan Kazimierz University he had learned over 14 languages and showed strong aptitude and interest in international law. After a career as a prosecutor in Poland, he was forced to flee to Sweden to evade capture by the Nazi forces in 1939. However 49 of his relatives were tortured and/or killed, drops in the ocean of inhumanity that was the Holocaust. 2

After fleeing the Nazi invasion, Lemkin eventually made his way to the United States. There he became a prolific professor, lecturing at the law school at Duke University in 1941 and the School of Military Government at the University of Virginia in 1942. He also served as an adviser to the United States War Department specializing in international law. 3

The world first became aware of Lemkin’s concept of genocide after the publication of what would arguably be his most important work, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, in 1944. Primarily a legal analysis of the behavior of Nazi Germany in occupied territories during World War 2, the book also contained a full definition of the crime Lemkin dubbed “genocide.” 4 After this publication, Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to getting the international community to acknowledge genocide as a crime under international law.

Lemkin drafted a resolution for a treaty which would officially ban genocide under international law. He then took his resolution on the road, presenting it to any nation which would hear him, hoping to garner enough support to endorse a convention on the subject. After years of lobbying the international community, The United States UN delegation agreed to present Lemkin’s resolution to the General Assembly. Dubbed “The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” the resolution was adopted on December 9th, 1948. It would be another 3 years before enough countries signed on the the convention to make it enforceable. Much to Lemkin’s dismay, The United States was not one of the first 20 signatories. 5

Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to lobbying those nations which had not yet signed onto the convention, with the United States being his primary target. He invested every moment of his time and every cent of his modest wealth to landing that particular white whale. He eventually died of a heart attack, impoverished, unemployed, and underappreciated, in 1959. His funeral was a small affair, reportedly only attended by 7 people. 6 Yet, today, the is no Law School, no class that teaches Human Rights, nor any conversation of World War II and any of the subsequent Genocides that does not mention his name. More importantly, the Convention provided some tools to prevent or punish such cases.

The greater legacy of his life’s work would not be realized until several decades after Lemkin’s death. The United States would eventually sign the Genocide Convention, but not until 1988. The international community would eventually convict a man of the crime Lemkin coined, but not until the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1998 which found Jean-Paul Akayesu guilty of the Rwandan genocide. Three years after that, Radislav Krstic was similarly convicted for the murder of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in Yugoslavia. 7 Though he died nearly 40 years too early to see the fruits of his labor truly flourish, we can hope that his soul finds solace in the fact that, thanks to him, these heinous actions have a name and are viewed the world over as being among the worst crimes humanity has ever known. Eradicating the crime of genocide still eludes us but at least accountability is now more widespread around the world. 8

- Donald Niewyk and Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University, 2000), 43. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- Rafael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress, (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Department of International Law, 1944) pg. 79. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Jay Winter, “Prophet Without Honors” The Chronicle, June 3, 2013, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Raphael-Lemkin-a-Prophet/139515 . ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- United Nations, “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” United Nations Treaty Collection, 78:1, 1021 (9 December 1948), New York: United Nations, 1951, 278-311. ↵

196 comments

Sofia Resendiz

I have heard the word genocide many times before, especially when referring to the holocaust but I never thought of the origin of the word. Before reading this article I only saw genocide as another word we learn, but after reading this article I see value in the word. His works and attempts were great and it is sad to know that he died thinking his word was a failure.

Emily Jensen

Congratulations on your nomination for an award, truly a fascinating article to read! It is sad to think about that his recognition did not come full circle until after his death, that he was unable to see just how impactful his work was. It is incredible that he was able to accomplish all that he did in his relatively short lifespan.

Eric Ortega Rodriguez

Wow, this article is fascinating. I have never heard of Raphael Lemkin or what he did, and I wish I did. What he did in the aspect of human rights is incredible. He was able to give a name to something that did not have one before had which led to future crimes to have a name to go by. With his knowledge in international law, he was able to define what genocide is. Sadly, it was not until after his death that his work actually took off. Overall, a very interesting article and something I would like to look more into. Great work.

Jocelyn Moreno

I can’t believe that if he hadn’t fought to have genocide be seen as a crime, it would have been “allowed”. The article was very well written and your introduction was one I could not stop reading! What he had done is unrecognized by millions when he should be known by millions! Great article !!!

Cooper Dubrule

It is amazing to read a story about a man, Raphael Lemkin, who was once oppressed and under the constant danger brought forth by the Holocaust, escape and gain influence to fight for those who were once in his shoes. By defining what genocide was, Lemkin brought light upon how it is an issue to the masses. Overall great article. It was very informative. Congratulations on your nomination.

Megan Copeland

I think the article was very well written because it draws the reader in and makes them want to read the rest of the story. I think what he did for the human race was so awesome. He changed so many things in regards to human rights. I think is sad that he did not get to see his incredible impact on the world. Something that I found really interesting was that some people did not believe mass murder to be illegal.

Luke Lopez

This is a very interesting article on Raphael Lemkin and his coining of the word “genocide”. It is a shame that more countries did not sign off on Raphael Lemkin’s resolution for officially banning genocide internationally when he was still alive. Overall, this was a great article that detailed the life of Raphael Lemkin, and his coining of the word “genocide”.

Jose Fernandez

This is a great article! It is very informative and it has the necessary facts to allow the reader to understand the story. Congratulations on the nomination for the ceremony. I didn’t know about the work of Dr. Raphael Lemkin, and I think his impact on international law is outstanding. I didn’t know the origin of the word “genocide”. I also found interesting that he knew that many languages. Good job!

Ysenia Rodriguez

Congratulations on your article’s nominations in three different categories! That is an amazing accomplishment. Your article brought an interesting topic into light and one can only imagine where the world would be without the work of Raphael Lemkin. It is a shame that Lemkin did not live to see his life’s work become a very serious matter across the world, however his hard work did pay off thankfully. Good luck during the award ceremony!

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. What Lemkin did is truly incredible. He coined a phrase that people now recognize, and because of that recognition the international community can now hold people accountable for these heinous crimes. I wish that Lemkin could have been around to see his life’s work be put to use to hold others accountable. But unfortunately he did not. Still though he did define for us the word of genocide and now because of him we can hold others accountable.