At a quiet New York cemetery in 1959, a handful of people stand around a fresh grave as a casket is lowered. Any passerby seeing the small somber ceremony might assume that the body belonged to a person of little significance. In fact, this casket carries the body of a man who is responsible for one of the largest shifts in international law in human history. Without his efforts, it is likely that the gravest crime mankind has ever committed and continues to commit would still be a crime without a name.

By the end of World War II, the Nazi regime had orchestrated the murder of over 17 million civilians in concentration camps throughout Europe. 1 Despite these egregious atrocities, no one at the time referred to the Holocaust as an act of genocide, not because it was not an appropriate descriptor, but because Raphael Lemkin had not yet coined the word and defined the crime for the world. The outcome of his personal crusade to encode ‘Genocide’ in an internationally recognized and binding Convention to which the US would sign on became his legacy (the US signed on decades after his passing).

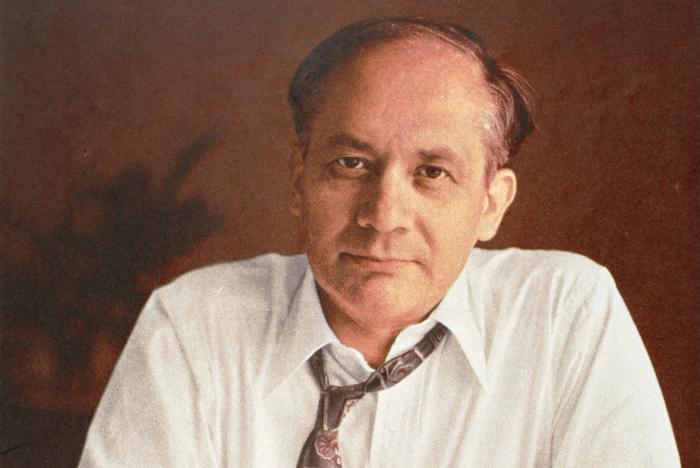

Lemkin was born to a Polish-Jewish family in 1900 in a small village called Bezwodne in what was then The Russian Empire. Home schooled by his mother, he proved to be a brilliant scholar. By the time he received his undergraduate degree from Jan Kazimierz University he had learned over 14 languages and showed strong aptitude and interest in international law. After a career as a prosecutor in Poland, he was forced to flee to Sweden to evade capture by the Nazi forces in 1939. However 49 of his relatives were tortured and/or killed, drops in the ocean of inhumanity that was the Holocaust. 2

After fleeing the Nazi invasion, Lemkin eventually made his way to the United States. There he became a prolific professor, lecturing at the law school at Duke University in 1941 and the School of Military Government at the University of Virginia in 1942. He also served as an adviser to the United States War Department specializing in international law. 3

The world first became aware of Lemkin’s concept of genocide after the publication of what would arguably be his most important work, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, in 1944. Primarily a legal analysis of the behavior of Nazi Germany in occupied territories during World War 2, the book also contained a full definition of the crime Lemkin dubbed “genocide.” 4 After this publication, Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to getting the international community to acknowledge genocide as a crime under international law.

Lemkin drafted a resolution for a treaty which would officially ban genocide under international law. He then took his resolution on the road, presenting it to any nation which would hear him, hoping to garner enough support to endorse a convention on the subject. After years of lobbying the international community, The United States UN delegation agreed to present Lemkin’s resolution to the General Assembly. Dubbed “The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” the resolution was adopted on December 9th, 1948. It would be another 3 years before enough countries signed on the the convention to make it enforceable. Much to Lemkin’s dismay, The United States was not one of the first 20 signatories. 5

Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to lobbying those nations which had not yet signed onto the convention, with the United States being his primary target. He invested every moment of his time and every cent of his modest wealth to landing that particular white whale. He eventually died of a heart attack, impoverished, unemployed, and underappreciated, in 1959. His funeral was a small affair, reportedly only attended by 7 people. 6 Yet, today, the is no Law School, no class that teaches Human Rights, nor any conversation of World War II and any of the subsequent Genocides that does not mention his name. More importantly, the Convention provided some tools to prevent or punish such cases.

The greater legacy of his life’s work would not be realized until several decades after Lemkin’s death. The United States would eventually sign the Genocide Convention, but not until 1988. The international community would eventually convict a man of the crime Lemkin coined, but not until the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1998 which found Jean-Paul Akayesu guilty of the Rwandan genocide. Three years after that, Radislav Krstic was similarly convicted for the murder of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in Yugoslavia. 7 Though he died nearly 40 years too early to see the fruits of his labor truly flourish, we can hope that his soul finds solace in the fact that, thanks to him, these heinous actions have a name and are viewed the world over as being among the worst crimes humanity has ever known. Eradicating the crime of genocide still eludes us but at least accountability is now more widespread around the world. 8

- Donald Niewyk and Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University, 2000), 43. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- Rafael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress, (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Department of International Law, 1944) pg. 79. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Jay Winter, “Prophet Without Honors” The Chronicle, June 3, 2013, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Raphael-Lemkin-a-Prophet/139515 . ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- United Nations, “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” United Nations Treaty Collection, 78:1, 1021 (9 December 1948), New York: United Nations, 1951, 278-311. ↵

196 comments

kparedes1

This article does an amazing job of emphasizing Raphael Lemkin’s impact on international law. It can easily be observable as to the type of person Raphael was because he continously fought against genocide. It is an eye opener to see how much someone loses behind doors for the greater good. People will always look at your greatness and rewards but never the struggles behind it. The infographics were well structured and visually eye-catching. The captions under each photo make the article more captivating in general.

egonzalez95

Good evening, Matthew. I hope all is well. I loved that you provided insight into this historical figure. I was surprised to find out who Raphael Lemkin was and what he did for the people. I understand now the various ways he went public to take on the fact that the Nazi War was a genocide, and people did not realize it since they were unfamiliar due to no one not being able to coin the term. As time passed, Lemkin was known to learn 14 languages, which is very impressive. I love that he was intrigued by international law and lobbied many countries, especially the United States, to acknowledge genocide as a crime under international law. The United States’ hesitation to approve of that law was the main reason Lemkin was still willing to fight and make the genocide known all over the world. I admire what Lemkin did in the past and how you, Matthew, can be a part of that solution with the rest of us. Thank you for this article. It was very informative for me to learn and gain insight into what happened to people from the past.

igutierrez14

Very sad story for this man who dedicated his life to a monumentally great cause. It makes us reflect on our own lives and realize that many of our efforts might not gain their full impact on others until we are long gone. Sad to hear of the U.S. low involvement.

A'marie Pollard

Learning about the history of Ralph Lemkin and his passion for international law is surreal. To think that Mr.Lemkin drafted a international ban on genocide. His dedication was undeniable. He travled looking to share his treaty with anyone who would listen. He dedicated his life to making a difference. I never heard of Ralph Lemkin but I am certain he will be a name that I will never forget.

Nicole Estrada

Whoa! Raphael Lemkin is a man I’ve never heard of, but I really admire the work that he created. I wish he had lived a little while longer to witness the growth and recognition of his work. Especially with the war going on and the Gaza-Palestine situation. Given his prominence in international law, I find it shocking that he isn’t more well-known in the world. His life and career were covered in great depth in this fascinating piece!

Gaitan Martinez

I do remember reading about this man, his story was astonishing and its absurd to find out the term, “genocide was created after the Holocaust.” You would think after all the atrocious history that humans are responsible for, the term, “holocaust” would’ve already been created. Reminds me of the term, “bucket list,” you would think that term had been around for a while; however, it was barely created after the bucket list movie. Which is crazy!

Fernando Milian

What a wonderful and well-written essay to commemorate the legacy of a great man this is. It is always challenging to condense the life of a notorious historical figure into an article, but the author of this text meets that challenge gracefully.

For a student of Political Science, the name Lemkin rings a bell. As the text highlights, coming up with a definition to encapsulate what we know today as genocide was a big achievement in those years when the international instruments for its condemnation were still not recognize. Nowadays, we take for granted (the existence of international law) because most of us were born in a time of great acknowledgement for the protection of human rights and the collective disapproval of massive crimes like genocide, but we shall remember that it was not always like that. In that sense, Wyatt’s essay accomplishes a tremendous service by giving the necessary recognition to figures like Raphael Lemkin.

Joseph Reed

Etymology, the study of where words come from, is an interesting and seldom looked at field; however, the background behind what caused the development of the word can be just as important as the word’s meaning. In this case, I did not know that the term genocide was so recent; I had figured that it originated around the turn of the 20th century.

Carina Martinez

Such a bittersweet account of the history of Raphael Lemkin and his contributions to the world. This was a very informational reading. I feel with the recent climate of the world and the current genocide happening in Palestine, this reading is very useful. It is very saddening to hear how Mr. Lemmings work went unnoticed during his lifetime, but he has helped named one of humanity’s worse crimes.

Lauren Sahadi

I have never heard of Raphael Lemkin before. Reading about how he left his mark on international law was very interesting. He had to witness the horrors of the Holocaust, and decided to try to make a change. He didn’t see the extent of his work, but he loves on through the Genocide Convention. This article was very well written and informative, great job.