At a quiet New York cemetery in 1959, a handful of people stand around a fresh grave as a casket is lowered. Any passerby seeing the small somber ceremony might assume that the body belonged to a person of little significance. In fact, this casket carries the body of a man who is responsible for one of the largest shifts in international law in human history. Without his efforts, it is likely that the gravest crime mankind has ever committed and continues to commit would still be a crime without a name.

By the end of World War II, the Nazi regime had orchestrated the murder of over 17 million civilians in concentration camps throughout Europe. 1 Despite these egregious atrocities, no one at the time referred to the Holocaust as an act of genocide, not because it was not an appropriate descriptor, but because Raphael Lemkin had not yet coined the word and defined the crime for the world. The outcome of his personal crusade to encode ‘Genocide’ in an internationally recognized and binding Convention to which the US would sign on became his legacy (the US signed on decades after his passing).

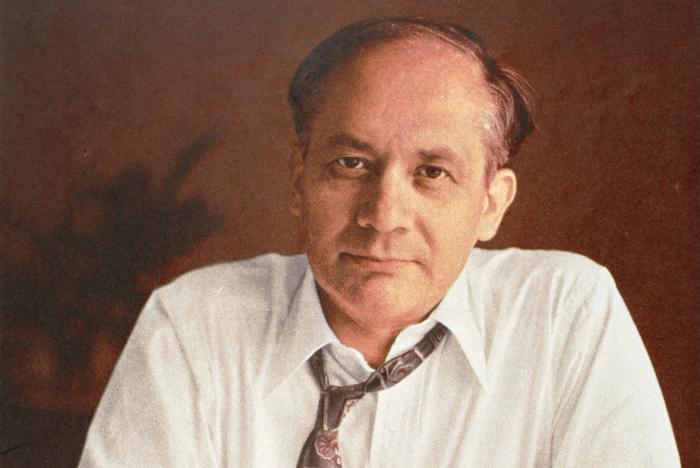

Lemkin was born to a Polish-Jewish family in 1900 in a small village called Bezwodne in what was then The Russian Empire. Home schooled by his mother, he proved to be a brilliant scholar. By the time he received his undergraduate degree from Jan Kazimierz University he had learned over 14 languages and showed strong aptitude and interest in international law. After a career as a prosecutor in Poland, he was forced to flee to Sweden to evade capture by the Nazi forces in 1939. However 49 of his relatives were tortured and/or killed, drops in the ocean of inhumanity that was the Holocaust. 2

After fleeing the Nazi invasion, Lemkin eventually made his way to the United States. There he became a prolific professor, lecturing at the law school at Duke University in 1941 and the School of Military Government at the University of Virginia in 1942. He also served as an adviser to the United States War Department specializing in international law. 3

The world first became aware of Lemkin’s concept of genocide after the publication of what would arguably be his most important work, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, in 1944. Primarily a legal analysis of the behavior of Nazi Germany in occupied territories during World War 2, the book also contained a full definition of the crime Lemkin dubbed “genocide.” 4 After this publication, Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to getting the international community to acknowledge genocide as a crime under international law.

Lemkin drafted a resolution for a treaty which would officially ban genocide under international law. He then took his resolution on the road, presenting it to any nation which would hear him, hoping to garner enough support to endorse a convention on the subject. After years of lobbying the international community, The United States UN delegation agreed to present Lemkin’s resolution to the General Assembly. Dubbed “The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” the resolution was adopted on December 9th, 1948. It would be another 3 years before enough countries signed on the the convention to make it enforceable. Much to Lemkin’s dismay, The United States was not one of the first 20 signatories. 5

Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to lobbying those nations which had not yet signed onto the convention, with the United States being his primary target. He invested every moment of his time and every cent of his modest wealth to landing that particular white whale. He eventually died of a heart attack, impoverished, unemployed, and underappreciated, in 1959. His funeral was a small affair, reportedly only attended by 7 people. 6 Yet, today, the is no Law School, no class that teaches Human Rights, nor any conversation of World War II and any of the subsequent Genocides that does not mention his name. More importantly, the Convention provided some tools to prevent or punish such cases.

The greater legacy of his life’s work would not be realized until several decades after Lemkin’s death. The United States would eventually sign the Genocide Convention, but not until 1988. The international community would eventually convict a man of the crime Lemkin coined, but not until the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1998 which found Jean-Paul Akayesu guilty of the Rwandan genocide. Three years after that, Radislav Krstic was similarly convicted for the murder of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in Yugoslavia. 7 Though he died nearly 40 years too early to see the fruits of his labor truly flourish, we can hope that his soul finds solace in the fact that, thanks to him, these heinous actions have a name and are viewed the world over as being among the worst crimes humanity has ever known. Eradicating the crime of genocide still eludes us but at least accountability is now more widespread around the world. 8

- Donald Niewyk and Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University, 2000), 43. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- Rafael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress, (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Department of International Law, 1944) pg. 79. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Jay Winter, “Prophet Without Honors” The Chronicle, June 3, 2013, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Raphael-Lemkin-a-Prophet/139515 . ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- United Nations, “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” United Nations Treaty Collection, 78:1, 1021 (9 December 1948), New York: United Nations, 1951, 278-311. ↵

196 comments

lsahadi

I wasn’t too familiar with genocide and the history of it. This article shed some light on the matter to me and how serious it really is. The subject matter was super interesting and the author did a great job conveying the story. Rafael Lemkin worked so hard and never got to see his work come into play. He did a good service and his work shouldn’t go unnoticed.

ajuarez15

I really like how this article goes more in depth about Lemkin’s accomplishments and who he was. It is very unfortunate how he did not get the recognition he deserved until years later. But we will for sure know him as the man who saved thousands of lives. Because of Lemkin, Genocides were officially banned under international law. I do however wonder why it took the United States 40 years to finally sign the Genocide Convention.

Fernando Garza

What a great article, the setup of the setting in the intro is a great attention grabber! However, as I would assume to be the intended effect, the article felt bittersweet. Listing out and telling us about Dr.Lemkin’s accomplishments and his background made me emotionally invested in him. Hearing not only how he passed but also that he hadn’t witnessed his accomplishments left behind a sour feeling, however knowing of the eventual progress his work saw even after he passed reminded me that somethings surpass individual lifetimes and have lasting effects on the world as we know it and shape it.

A'marie Pollard

Learning more about such a traumatizing event through your infographic has helped me to further my knowledge. I feel being better informed about this topic was both necessary and crucial as a college student. The hardships that Raphael Lemkin experienced is surreal. He is an exceptional man who dealt with a variety of different hardships but he never let that define him. He came to America and taught at Duke University. Raphael brings awareness to an important issue. Genocide is serious and it needs to be talked about more. Thank you for the infographic.

sbenavides11

Giving a brief introduction to Raphael Lemkin’s life was very interesting and helpful in understanding the timing of the storytelling of the article. It’s quite unfortunate that he spent the remainder of his life lobbying and trying to make a substantial difference. However because of this published article we as a community can come together and try to make a difference in his honor,such as advocating his legacy and cause.

jsanchez152

I had never heard of Raphael Lemkin before reading this article and his story is inspiring. It is not surprising that the person responsible for the coining of the term genocide had to suffer the loss of 49 relatives to the crime. I wonder why the US withheld from adopting the term for so long, hopefully not because they were afraid of being found guilty of the crime in the past…

But I digress, I appreciate you writing this article and giving the man who fought against the greatest human injustice some justice in spreading his name and attaching him to the infamous term “Genocide”.

mguerrero26

This article left me with a flabbergasted expression. Raphael Lemkin was underrated, overlooked, and unvalued. He was way ahead of his time and no one realized it. This was an interesting and engaging article. Great work on film highlighting the life of a man whom many people may not be familiar with but who played a vital and essential influence in today’s international legislation.

Ana Barrientos

Wow! I have never heard of Raphael Lemkin but his work is admirable. I wish he would’ve lived a little bit longer to see his work flourish and get recognized. I’m in shock to see that he isn’t talked about within the law community, since he is in important person in international law. This article was interesting and gave great detail about his life and work! Overall, great job!

Haley Aleman

I find it very surprising that even though the crime of genocide has been committed for far too long that one of the first convictions was not until 1998. I am further disturbed to learn that both of my parents had been born before 1988 when the United States signed the Genocide Convention. Even though the acceptation and enforcement of the Genocide Convention came much later than I would have liked, I am glad that Raphael Lemkin devoted so much of his time and efforts towards the Genocide Convention that would allow us in a legal sense to hold those who are guilty of these many and ongoing atrocities to be held accountable. Though his work was incredibly undervalued in his time, he is appreciated and held in high regard after his passing. Great article Matthew.

arealyvasquez1

It is truly fulfilling knowing that someone like Raphael Lemkin, who dedicated his life to accomplishing something for the greater good of the people, was able to achieve his goal of creating a world that implements accountability. He started his journey by seeking justice for his family that was wrongfully persecuted and turned it into a movement that would be taught to millions of people decades after his death. Even though he struggled to establish a worldwide consensus that genocide is known as the worst crime a person could commit, he persevered and continued his pursuit not only for justice for those who fell prey to the evil of others but for the people of future generations that wouldn’t have a voice after they are gone. Lemkin fashioned a new society that gave them their voice back, a voice that demanded justice and the impediment of future crimes.