Former First Class (FPFC) Robert M. Storeby was just like most men in the United States. He was proud of joining the army to contribute to his country as a way of showing gratitude. However, he did not know what was waiting for him. The reality that Storeby saw was one he wished that he could not remember. Born and raised in northwestern Minnesota to a family that struggled to get along, Storeby was fascinated by the landscape of the Asian country. Storeby traveled across the world to fight in a country where everything was underdeveloped and nearly destroyed after a previous war against the French. However, the scenes of the flourishing paddy fields, intertwined tropical jungles, and imprisoning patches of high elephant grass, were different from the frosted pastures of his hometown, of which he was used to. As an infantryman, Storeby had seen a considerable amount of operations; therefore, if he could choose, he would rather remember about the time he was pinned down, and half of his unit was injured. Nonetheless, the image of a Vietnamese village woman never once left his mind. She was twenty years old at the time, and came from a remote hamlet of Cat Tuong, in Phu My District, which was about a few miles west of the South China Sea.1

On November 17, 1966, one day before a reconnaissance was to take place in a small village, Storeby and two other squad members, Cipriano S. Garcia and Joseph C. Garcia, were told by Sergeant David Edward Gervase and Private First Class, Steven Cabbot Thomas, who were both members of C Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry, and 1st Cavalry Division, that they planned to kidnap a blossoming, charming girl during the upcoming reconnoitering mission, and at the end of the fifth day, they would kill her.2 He recalled that Gervase insisted that it would be “good for the morale of the squad.”3 Storeby had not been on the same page with them from the beginning. Though he could do nothing about it, he did not get involved in the crime. However, he did report the incident to a commander.

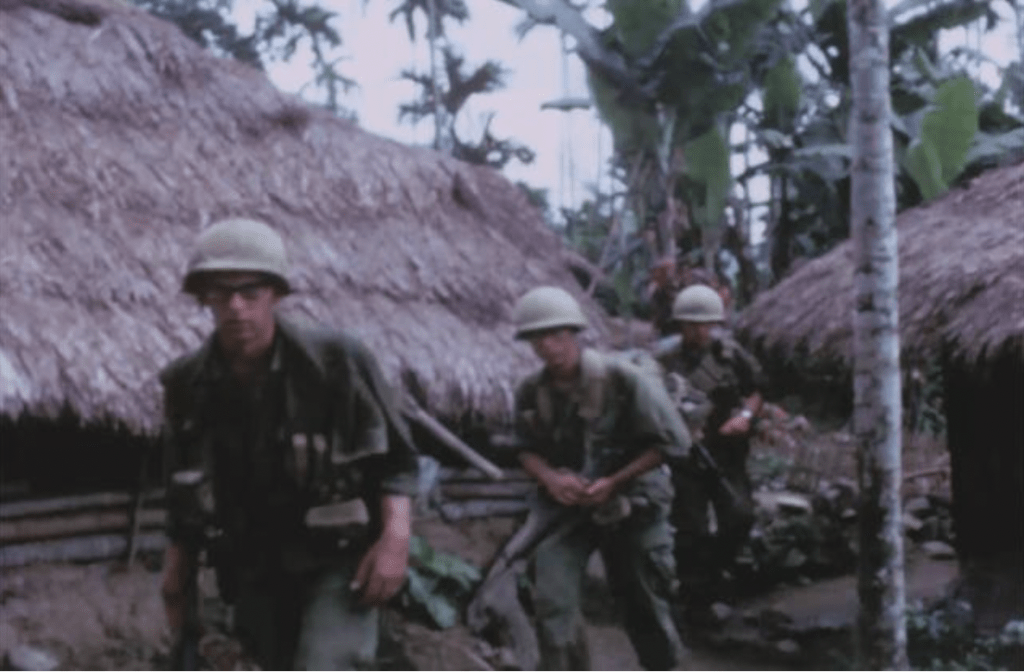

At exactly 5:00 a.m on November 18, 1966, a few hours before the reconnaissance mission happened, they began to mission that the Lieutenant described as “extremely dangerous.”4 Five commissioned men, including Storeby, went on a counterespionage mission in a tiny rustic village looking for their target. The men were approaching the town, and Storeby was cursing himself for having agreed to go along with his comrades. In distrust and confusion, his heart pounded rapidly as the adrenaline ran through his veins. He saw that Thomas did not lose a second in carrying out his plan. With Garcia following him, the Sergeant had commenced a well-organized hunt through the hamlet. He had not found a single girl from five or six cottages that they raided. Then Joseph spotted a white hut and shouted, “There’s a pretty girl in there! She has a gold tooth!” Immediately, Gervase said, “That’s the girl we’ll find.”5 Storeby remembered that the unit then quickened their steps to jerk her from the hut where she was sleeping with her family.6 They then used a rope to bind and gag her and took her on duty.

Storeby did not remember much about the girl’s looks; however, he did remember that she had a “bodacious gold tooth and that her eyes were purely dark brown, and could be significantly sententious”.7 Like most bucolic women, she dressed in traditional loose-fitting black pajamas called “áo bà ba.” He knew her for only twenty-four hours before she was stabbed three times then shot in the head, which ultimately led to her death. They were the last people that she ever saw. For the time she had lived, Storeby hardly exchanged a word with her, since neither of them spoke the other’s languages. He did not know her name at that time; it wasn’t until her sister identified her in a court-martial proceeding that he eventually learned her name—Phan Thi Mao—the name that would, later on, shadow him for the rest of his life.8

Leaving the hamlet with the girl as their prize, the squad moved west toward the main tracks. There was a cry of agony that ceased them when they hardly had departed twenty meters away from the village. It was Mao’s mother, Storeby recalled, who was chasing them with the hope of begging them to release her daughter. One of the members testified at the court, “The mother came out, like they always do, started crying, talking. We just tell them to dee dee (đi đi)”- meaning to go away.9 Having reminisced about the scenery, Storeby remembered noticing an austere woman waving her scarf, which is known by the Vietnamese as “khăn rằng.” She thrust herself toward them in great desperation. Ultimately, she reached them, talking in her panting that the scarf was Mao’s and that she would like Mao to have it with her; she was prostrated with tears flowing down her cheeks. Perchance, from deep down, the mother realized that she would never see her innocent, naive child again. The situation was incommodious, Storeby recalled. Having received the scarf, Thomas spread a smile across his face, and Stroreby was conscious of his intention. Just then, Thomas used the scarf to stuff her mouth to prevent her from yelling for help. Later on that day, after settling down in a forsaken hovel, and having a wholesome snack outside the hootch, Gervase looked at his fellow man as if he was up to something, and said that “It’s time to have some fun.”10

Sensing Storeby’s disapproval, the Sergeant confronted him, wanting to know whether he would go into the hut with him or not. Storeby shook his head. Thomas warned him that he was in danger of being reported as “a friendly casualty” for not joining them in a horrible crime. Still, he shook his head. Thomas did not give up. He tried to attack Storeby’s masculinity by calling him “queer” and “chicken.”11 Despite his effort, Storeby still gave him a solid, firm no.

The Sergeant was the first who went into the hut, and soon after Storeby heard a pitchy, painful moaning coming from inside the hootch. Storeby deeply felt sorry for the girl; a young virgin that went through so much pain. The sound of her sobbing kept repeating as the other four soldiers kept molesting her. Storeby was outside at that time; he could not do anything but feel sorry for the girl. Having satisfied their desires, the others took off and left Storeby alone to guard her and their weapons. Storeby then said that “even though they were two different people, speaking two different languages, and that he could not understand her back then, somehow, there was a connection between them. He felt like he knew her well enough, her futile cries in the latency on the hill 192”.12 He did not know how to act around her, how to behave.13

After thinking, Storeby decided to go into the hutch to check on her. He said, “When Mao saw me come into the hootch, she thought I was there to rape her. She began to weep, and backed away, cringing.”14 He noticed that Mao was very jaded and ill, and she seemed to get worse as time went by. He had a feeling that Mao was injured; however, he did not know for sure because she was covered by her black pajamas. The soldier gave her crackers, water, and beef stew—it was her first meal since she was kidnapped from her home. Storeby remembered that she kept staring at him with her wary doubtful eyes as if she was trying to figure out what game he was playing with her. Mao then hardly mumbled something that Storeby guessed was “Thank you.”15 Storeby wanted to tell her that he was sorry for his fellow men’s act, for their horrible crimes, yet the language barrier made that very difficult. He wished he and she could communicate, so that Mao could tell him what she wanted, because, after all, it is her life that is in danger, not his. Storeby stepped outside to be by himself. It was then that he started to have all the conflicts in his consciousness. He was in two minds as if he should let her flee or keep her there. Little did he know that his members were then four hundred meters away, on the Hill 192, and it would take them about an hour to return back to the hut. He had the chance to rescue the girl, to save this person’s life, yet as a self-restrained soldier, he could not use the excuse that she overpowered him. He felt powerless.

The night went by. In the morning, they woke up shortly after six. It was then that he knew what would happen to Mao. They were about to kill her and report it as a K.I.A- Killed in action.16 However, it was then that they were attacked by the Viet Cong. In the middle of the firefight with communist Viet Cong, for fear that she would be seen with the squad, Thomas took her to a secluded area and without hesitation or mercy, he stabbed her three times. Despite her being stabbed, she was still alive. She then tried to flee from them in spite of knowing her chance of surviving was small. Thomas finally caught her and cold-bloodedly shot her in the head with his M16 rifle.17 The event happened so fast that Storeby had not been fully aware of the situation.

Having found out that they killed Mao in this way, he began to have guilty feelings that urged him to take actions against them, to make them pay for what they did. With that in mind, Storeby went up to the chain of command, to the captain. However, he turned a blind eye on the horrendous act that was committed by the American soldiers. Storeby then was threatened by those who had been involved in the crime. They threatened to kill him; however, he still insisted on reporting their crime to higher authorities. His effort paid off, as a court-martial took place in Viet Nam. The army had to fly the judge, whose name was Durbin, all the way from America. It was at the court that Mao’s sister, Loc, identified her sister’s body, and it was there that Storeby testified to the whole story. It was then that the ugly truth of war was revealed internationally. The court ended with Thomas being sentenced to prison for life despite the prosecutor’s proposal that he should have received the death penalty. Gervase was sentenced for ten years, Joseph Garcia received fifteen years in jails, and Cipriano had four years of confinement.18 Consequently, four of them were dishonorably discharged from the Army.

Even though Storeby’s fellow men were sentenced to prison, his life was still in danger. This led to him being placed in the witness protection program. It was not until Daniel Lang published a book about the story that the world was made known of the incident. Twenty years after the trial, the court-martial, and the story of Storeby and Phan Thi Mao, the Columbia Pictures company was inspired to produce the movie Casualties of War.19

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Frederic L. Borch III, Judge Advocates in Vietnam: Army Lawyers in Southeast Asia 1959-1975 (Darby PA: DIANE Publishing CO., 2003), 71. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Tom Fitzpatrick, “There is yet more to Casualties of War,” Phoenix New Times, August 30, 1969. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,”New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Daniel Lang, “Casualties of War,” New Yorker 45 no. 41 (1969): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1969/10/18/casualties-of-war. ↵

- Frederic L. Borch III, Judge Advocates in Vietnam: Army Lawyers in Southeast Asia 1959-1975 (Darby PA: DIANE Publishing CO., 2003), 71. ↵

- Frederic L. Borch III, Judge Advocates in Vietnam: Army Lawyers in Southeast Asia 1959-1975 (Darby PA: DIANE Publishing CO., 2003), 71. ↵

- Frederic L. Borch III, Judge Advocates in Vietnam: Army Lawyers in Southeast Asia 1959-1975 (Darby PA: DIANE Publishing CO., 2003), 71. ↵

39 comments

Guadalupe Altamira

I know war can make people do terrible things because it’s war but I wasn’t aware it was to this extent. The cruel and hurtful things they did to women during that time are just disgusting. We expect our soldiers to return with honor that they served their country but behind all, that honor is men who did awful things. The poor women having to live those memories of what happened is just horrible and it makes it worse that they didn’t get justice in the end. Great article to shed light on this topic

Phylisha Liscano

This story is so upsetting, I can’t imagine how that poor girl felt. Those men are so disgusting. for taking advantage of their title.The fact that many look up to them for their courage but yet behind scenes they are doing such horrible acts. Makes it so hard for me to trust those men. Image the women who are now have joined the army, it’s very upsetting that they have to worry about their safety from American soldiers.

Donal O'Sullivan

Judging by the comments it is pretty clear people don’t realise the perpetrators of this heinous crime did practically no time in prison. Meanwhile the whistleblower had to enter witness protection. So many whistleblowers end up persecuted or committing suicide. What happened to the company commander who took no action on receiving Storeby’s report? He should have been punished for leaving Storeby ‘out in the cold’.

Edward Cerna

This is such a horrible to story to read and it is truly upsetting that American soldiers acted like this. I am happy that Thomas got sentenced to life and not death so that he can sit in a prison cell forever and regret what he did. This article demonstrates just how evil mankind can be and especially during a time of war. Although he did not save her, in a way he redeemed himself by getting justice to those who were involved. This was a very excellent article.

Evangelina Villegas

This is truly an upsetting story to read and even more heartbreaking in knowing that it is a completely true story at that. This just shows one of many atrocious acts that were committed in the face of war. Oftentimes many people who experience war, either fighting in one or trying to survive from one, will be forever changed, some will even go as far as to cause others to suffer for their own pleasure. The Vietnam War was a never ending war that led to the suffering of both sides and it was, in reality, a pointless war that was filled with nothing but hopelessness. The most gut- wrenching part of this article was the mother. As her daughter was being taken away, she had given her daughter’s scarf to her knowing that was going to be the last time she would ever see her child. Knowing that you are losing your daughter to a fate that will be worse than death and knowing that there is nothing you can do has to be the most terrible thing in the world. The sad and awful thing about wars is that war often brings out the worst in humanity, rape and genocide being some of the most known ones to be recorded. People will eventually lose sight of who they are and will start to view others as their enemies not as other human beings. It is truly sad to know that because of wars so many people will never get the chance to live.

Ryan Cooney

I remember my dad letting me watch casualties of War when I was 11. It was such an upsetting movie and then to find out it was based on a true story a few weeks after watching it stuck with me to this day. That poor young woman got no justice. She never got a chance to live a long life marry have children or pursue a career.

Zachary Johnson

She did get justice because of Robert M. Storbey,

he was who Michael J. Fox’s Character was based on.

If not for him seeking justice, those bastards that committed the rape and murder would’t have been locked up.

Janie Cheverie

This truly is an unsettling story about the terrible things these men did to women. This article demonstrates the abuse of power against those who were unable to defend themselves. They did something wrong and their actions deserved consequences. This demonstrates how dark these events can truly be and will never be forgotten. Storeby standing by his morals at the risk of his own life was very admirable and reflects who he is as a person.

Nicolas Llosa

This article describes how the soldiers in Vietnam survived and all the actions that they did. A few years ago I read the book “The Things They Carried” and it talked about the Vietnam War. All the things they did were really cruel but they also experienced really bad things. Going to war isn’t easy and the problems that people have after going to war are really difficult.

Reagan Clark

This is truly despicable. Nothing about this story is ok. Nothing. Not even the soldier’s actions in the end. While he might have gotten her justice, he was part of the reason that she died. He could have released her to giver her a fighting chance when he was guarding her by himself but he did not. He was a coward who did not want to face his actions. The Vietnam war was one of the biggest downfalls of US history. It was a war that should never have been started. The US soldiers ruined countless lives. Horrible. Nothing about this war or their actions were honorable. Nothing about them ever will be. Nothing.

Mia Hernandez

This article was difficult to read. I can not believe that the men would do those monstrous things to girls. They took complete advantage of of their power and were not honorable men to the uniform. I found it disgusting when he said it was a “friendly casualty.” I don’t understand why they thought they were going to get away with it. They did something wrong and it deserved a consequence. I appreciate that Storeby stuck to his morals and said something about it even though there was a possibility of him getting punished. It was very admirable.