In the year 1936, Adolf Hitler made a decision that laid the foundation for the Second World War. The remilitarization of the Rhineland is viewed among historians as one of the first major violations of the Treaty of Versailles committed by Adolf Hitler, and it marks the first official step that led to the Second World War. Despite this action, taking place almost a century ago, there is still a certain mystery behind Hitler’s decision to take the risk to remilitarize. Many historians agree and acknowledge that there was clear and present pushback from many of his generals, as well as many risks associated with taking this action. So, what potential reasoning did Adolf Hitler have for rejecting the opinions of his leading generals, and risking potential conflict with France and its allies, risking his empire in its early years in order to remilitarize the Rhineland? While historians who have researched this question have differing views, they all agree that Hitler had clear strategic reasoning for taking this action, whether that be out of his fear and disgust over the Franco-Russian Alliance, or as a challenge to the vastly unpopular Treaty of Versailles, or to build on his growing popularity among the German people.

I argue that Adolf Hitler, while attempting to build on his growing popularity among the German people, made the decision to remilitarize the Rhineland, not only to put Germany on an equal playing field and reestablish it as a global superpower, but also to challenge the Treaty of Versailles and the Western powers. Adolf Hitler made this controversial decision to remilitarize the Rhineland in defiance of his generals because he knew the strategic benefits of doing so outweighed the unlikely possibility of any resistance from France or the other Western powers.

Adolf Hitler’s rise to power can be traced back to his role as an informant for the military. In early- to mid-1919, Hitler was chosen to be an informant for the German military, to monitor the meetings of political groups meeting in and around Munich. Hitler was on assignment to monitor the German Workers’ Party; he did not care much for the movement as he felt it was a “boring organization.” This changed, however, as Hitler gained popularity among the party’s leadership for challenging the opinion of one of its guest speakers. After attending this initial meeting, Hitler found himself drawn towards the movement.1

Adolf Hitler quickly grew within the party, with crowds attending each meeting, not for the purpose of partaking in the party, but to listen to Hitler’s speeches. Hitler’s role in the party grew exponentially due to his popularity, and he eventually rebranded the party as the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), and Hitler became the face of the NSDAP with most of the public not being aware that he was in fact not the chair of the party, but only a speaker at the meetings where thousands attended.2

As his popularity grew, and the party began to expand within Munich, Hitler and the NSDAP began to plan a Putsch in 1923 as an attempt to overthrow the government; however, this “Beer Hall Putsch” failed, and Hitler was arrested and imprisoned for his role. The NSDAP was also banned from partaking in elections. During his time in prison, Hitler wrote his now infamous book, Mein Kampf. After his brief stint in prison, Hitler returned empowered to a weakened movement. Hitler, for much of his early days, was an unknown, with only people in Munich and the surrounding area knowing about him. However, after his attempted putsch and subsequent trial, and with the publishing of his book, he became more well-known. With this new reputation, Hitler began to reshape his party and movement. The goal of this rebranding was to allow for the NSDAP to participate in elections, and by 1925, Hitler’s party had not only been allowed to partake in elections, but Hitler himself made a dramatic return to the political scene.3

Adolf Hitler and his party had difficulty gaining traction for the remainder of the 1920s, especially under the presidency of Paul von Hindenburg. This lack of popularity was apparent in the election of 1928, where the NSDAP gained relatively few seats in the Reichstag. Hitler, despite the lack of support, continued to give speeches and continued his movement. 1929 and the crash of the US stock market gave Hitler the opportunity he had been waiting for.4

The impact of the Great Depression was one of the final blows to the already unpopular Weimar Republic. The election of 1930 began to show the cracks in the Weimar Republic, and how the people of Germany were ready for change. In the 1930 election, the NSDAP had received 6.4 million votes—a major increase from the mere 800,000 they received just two years earlier. The root of this success came from the economic crisis and the Weimar Republic’s inability to properly handle the situation. This led to a severe distrust of the system, and the German people wanted something new, something reliable, and the populace saw these traits in the promises of the Nazi party.5

The year 1932 was the last year of the Weimar Republic. Elections held throughout the year showed that Hitler would one day rule Germany; it was just a matter of time. The first election of 1932 was the presidential election where war hero Paul von Hindenburg sought reelection against Adolf Hitler. Hindenburg failed to receive a majority vote, only receiving 49 percent. The German constitution dictated that the victor must receive over 50 percent of the vote to assume the office of the president. This forced a run-off election the following month for the office of the presidency between Hindenburg and Hitler, with Hindenburg winning, having received 53 percent to Hitler’s 36 percent.6 The results of these two elections showed that Hitler’s power was increasing with many of Hindenburg’s supporters voting in favor of Hitler, requiring Hindenburg to rely on the support of the Socialist Party, which he disliked. The two remaining elections of 1932 only increased the number of seats in the Reichstag for the Nazi party, making it the largest party in Germany. After President Hindenburg repeatedly refused to appoint Hitler Chancellor of Germany, in January 1933, Hindenburg had no other choice but to appoint Hitler chancellor, or allow the current Chancellor, Kurt von Schleicher, to stage a coup. This brought about the beginning of the end for the Weimar Republic.7

In the first year of Adolf Hitler’s chancellorship, many hoped that he would be easy to control, and while he made it seem like it, that was simply not the case. Upon entering office, Hitler immediately called for the dissolution of the Reichstag and planned for new elections to be held in March of 1933. Before the election could be held, the Reichstag caught fire, playing directly into the hands of Hitler and his party. They were able to use this fire to outlaw the Communist party (KPD), as it was believed that a Communist was responsible for the fire, taking yet another blow to democracy in Germany. The weakening of the other political parties allowed for Hitler and the Nazi party to expand their control of the Reichstag in the election of March 1933.8

March of 1933 saw yet another blow to democracy, when Hitler easily got the Enabling Act passed, allowing for Hitler to issue laws without needing the signature of President Hindenburg to put those laws into effect, effectively placing dictatorial power in the hands of the Chancellor. However, this was not the final blow; the final nail in the coffin of the Weimar Republic was also the nail in Hindenburg’s coffin when he died in mid-1934, allowing Hitler to become the sole leader of Germany.9 Adolf Hitler had finally become the sole leader of Germany and began to make many controversial actions without any resistance from the allies; one such action was the remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936.

On March 7, 1936, Adolf Hitler gave a speech to the Reichstag in which he announced that he had made the decision to remilitarize the Rhineland. This was announced along with the denunciation of the Treaty of Versailles. In this speech, Hitler detailed his reasonings and justifications for remilitarization, including his hatred of the Treaty of Versailles, claiming that it was unfair to Germany. This speech also saw Hitler claim that he did not seek conflict with any nation, and that he was even open to the possibility of one day rejoining the League of Nations, if the allied forces agreed to renegotiate the Treaty of Versailles. Hitler argued that he was simply pursuing equality for a Germany that had been terribly wronged in the Treaty of Versailles. One such wrong was the requirement that Germany demilitarize while other nations had the freedom to militarize at a moment’s notice to any region of their country. This is one of the key reasons, Hitler argued, for remilitarization of the Rhineland.10

Hitler went on to argue that he would have accepted the continued demilitarization as promised in the Rhine Pact of Locarno had France also promised to demilitarize. Hitler continued to argue that the Franco-Soviet Pact recently concluded was not only a direct violation of the Rhine Pact but also was a major threat to German security. In his speech, Hitler claimed that the alliance formed between France and the Soviet Union threatened the national security of Germany, and as a result, Germany had no other choice than to remilitarize the Rhineland. However, Hitler supported his decision by arguing that he in fact did not violate the Rhine Pact. He claimed that once France formed an alliance with the Soviet Union, that Pact ceased to exist, allowing him to take any action necessary to defend his nation. Hitler concludes his speech, by clarifying that the decision to remilitarize was not a threat to any nation, and that it was solely for the security of Germany.11

“In negotiations in recent years, the German Government has consistently stressed that it intended to abide by and fulfill all of the obligations arising from the Rhine Pact as long as the other contracting parties were willing, on their part, to stand by this Pact. This obvious condition can no longer be deemed to exist as regards France. France responded to Germany’s repeated friendly advances and assurances of peace by violating the Rhine Pact by virtue of a military alliance with the Soviet Union directed exclusively against Germany. Hence the Rhine Pact of Locarno has lost its inherent meaning and ceased, in a practical sense, to exist. As a consequence, Germany no longer views itself as bound for its part to this lapsed Pact. The German Government is now compelled to react to the new situation created by this alliance, a situation aggravated by the fact that the Franco-Soviet Agreement has been supplemented by a treaty of alliance between Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union with arrangements which are exactly parallel. In the interest of the primal right of a people to safeguard its borders and maintain its possibilities of defense, the German Reich Government has today re-established the full and unlimited sovereignty of the Reich in the demilitarized zone of the Rhineland.”12

The decision to remilitarize the Rhineland has been thoroughly discussed and researched by many historians. While each historian argues that Hitler had a different primary focus for his decision, they all agree that it was made for a strategic benefit. For the purposes of this article, I will be analyzing the arguments made by Ian Kershaw, Gordon Craig, Ruth Henig, and Zach Shore.

In his book entitled Hitler: Profiles in Power, Ian Kershaw argues at length what he believes Hitler’s reasoning was for deciding to remilitarize the Rhineland. Unlike other historians, Kershaw does not focus on the international strategic benefits and instead focuses primarily on Hitler’s popularity in Germany. Kershaw argues that if Hitler wished to be viewed as a nationalist and spread nationalism among the German populace, then he must reacquire the territory that had been taken from the German people. The idea of remilitarizing the Rhineland was relatively popular among the German masses, and if Hitler were successful in remilitarizing, as he was, his movement would gain popularity, even among those who did not identify with the Nazi party. Kershaw continues by arguing that Hitler chose to remilitarize at a strategic moment when the relationship between Britain and France was at its weakest, almost guaranteeing a lack of resistance to his movement.13

Kershaw further argues that the decision to remilitarize is one of the few actions taken by Hitler that had the potential of resulting in success without fear of retaliation. Kershaw argues that Hitler knew that if he acted in defiance of his generals and of the foreign office and was successful, it weakened the people’s respect and trust in those in office that opposed his actions. Being successful further cemented his position as Führer, and weaken the people’s trust in elected governments. Hitler was right in his beliefs as, after the success of the remilitarization, he garnered the support of the masses, and the masses whether Nazi or not, trusted Hitler as their leader.14

In his book Germany: 1866-1945, Gordon Craig argues that Hitler’s primary reasoning for remilitarizing the Rhineland was to establish prestige for Germany once again. The remilitarization was a major victory for the Nazi regime and brought about a sense of German nationalism that Hitler was rallying behind, as well as the subsequent effect of deteriorating France’s alliances with what the remilitarization uncovered.15

Craig argues that Hitler decided to remilitarize as a way to reveal the extent to which France had gone to defend the Rhineland. Craig acknowledges in his book, that France was ill-equipped to handle an invasion from Germany, and that French Generals had become aware of the potential risk of German retaliation caused by the Franco-Russian Pact. France in defensive measures was determined on expanding the Maginot Line along the Belgian border to combat an invasion from Germany. Craig argues that France was primarily focused on self-defense and had begun to ignore treaties established with Belgium in 1920 and 1925. Craig argues that Hitler exploited this action from the French and decided to remilitarize to weaken France by deteriorating its alliances. Hitler was successful in this, as Belgium shortly after the remilitarization took a stance of neutrality and withdraw from treaties signed with France.16 The weakening of France and the remilitarization of the Rhine proved to the world that Germany was once again a global power and was a force to be reckoned with.

In her book The Origins of the Second World War: 1933-1941, Ruth Henig makes the argument similar to what Adolf Hitler claimed his reasoning was for the remilitarization of the Rhineland. Henig argues that Hitler’s decision was a direct response to what they believed was a violation of the Rhine pact, and the potential threats posed to Germany by the Franco-Russian alliance. Henig continues her argument by acknowledging that the remilitarization of the Rhineland was not a surprise and both France and Britain had been aware of the impending move. Henig uses this acknowledgment to further her argument that Hitler had chosen to cross the Rhine river as a direct challenge to the Treaty of Versailles. She also argues that Hitler’s decision to remilitarize the Rhine was based on Britain wanting to renegotiate the terms of the Versailles treaty, and reduce the harsh terms placed on Germany in 1919.17 Henig’s argument makes it clear that Hitler decided to remilitarize as a way to open the door for renegotiating of the Treaty of Versailles to be more favorable to Germany.

In an article published in the Journal of Contemporary History entitled “Hitler, Intelligence and the Decision to Remilitarize the Rhine,” author Zach Shore argues that Hitler may have been made aware of the fact that France would not retaliate if Germany remilitarized. Historians agree that France was ill-equipped and unwilling to retaliate against Germany; however, this knowledge could not have been known to Hitler and his generals at the time. Shore argues that it is very possible that Hitler had been made aware of France’s unwillingness to fight, instead of basing his action on intuition and instinct, as most historians have argued.18

Shore further discusses the knowledge obtained by Foreign Minister Constantin Freiherr von Neurath, who had been given information detailing the situation in France that showed that France was aware of the remilitarization and was both unprepared and unwilling to retaliate against Germany. Shore argues that if Hitler had this information, it is very possible that he decided to defy the opinions of his generals to confidently move forward with the remilitarization and reap the strategic benefits without fear of potential retaliation from France or the other Western forces. While Shore was unable to guarantee that Neurath gave this information to Hitler, he was able to assume that it had, since Neurath was one of the few leaders close to Hitler that continued to push him towards remilitarization and was the only leader that reassured Hitler that France would not retaliate.19 So, while there is no proof that Hitler had been given the information acquired by Minister Neurath, it is clear that Neurath had the information and was one of the only leaders to continuously push Hitler towards remilitarization and to reassure Hitler that he would not face resistance.

While each historian focuses on a different aspect, whether it be to establish Hitler’s popularity as a nationalist, to weaken the Western powers, or to challenge the Treaty of Versailles, it is clear that the decision to remilitarize was made with strategic benefits in mind. It is clear that Adolf Hitler was capable of acting confidently, knowing that France would not act in retaliation, making the remilitarization of the Rhineland an action that guaranteed strategic benefits with little to no risks.

While the question why Adolf Hitler made the decision to remilitarize the Rhineland may never have a definitive answer, Hitler made a calculated decision in which the benefits outweighed any potential risks. It is clear that Hitler was aware of his military’s strength and could not risk his young empire on an action that resulted in resistance from France unless he was confident retaliation was unlikely. Hitler wanted his empire to grow and expand his popularity, effectively cementing his position as leader. To achieve this goal, Hitler started by rallying the nation, starting with the unification of all German peoples, including those in the Rhineland. The action of remilitarizing was a direct violation and challenge to the incredibly unpopular Treaty of Versailles, being successful proved that Hitler was a reliable leader for the German populace. Hitler knew that a calculated invasion of the Rhineland allowed for him to surge in popularity, that the benefits of such an action outweighed the potential risk of retaliation, and that there would be no retaliation to this action.

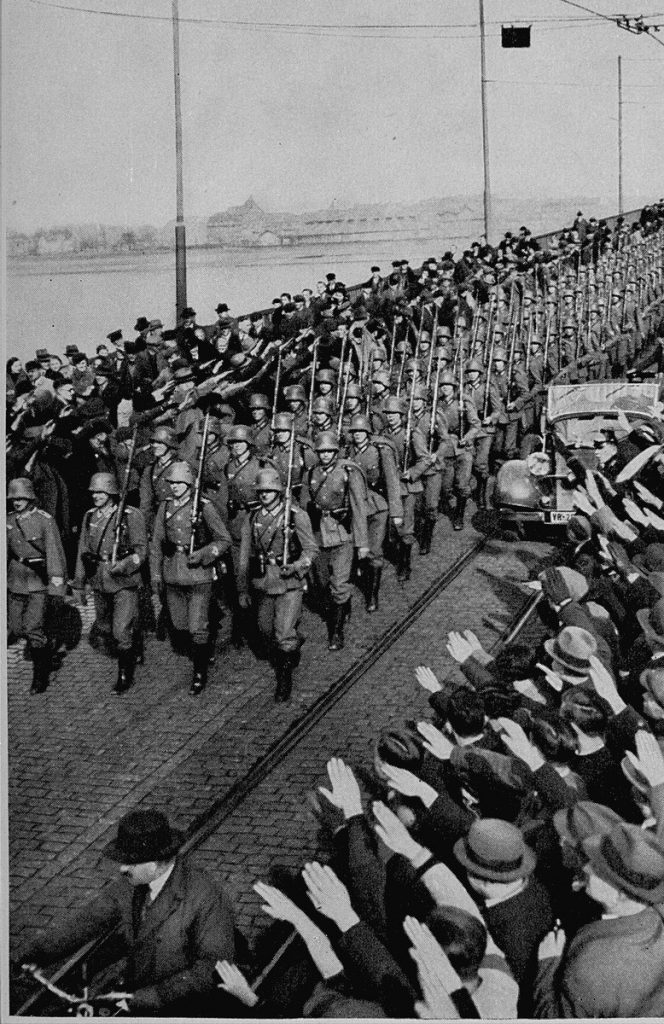

As argued by historians Kershaw and Gordon, the action of remilitarization was crucial in establishing a sense of nationalism in Germany and building upon Hitler’s existing popularity. The action of remilitarizing the Rhineland to unify the German people did in fact make Hitler extremely popular among Germans, even those who were not members of the Nazi party. Hitler had done what even his own generals feared doing, and as such placed populace support strictly behind Hitler, and weakened the people’s trust in other governing bodies.14 The impact on Hitler’s popularity was immediate, as upon entering the demilitarized zone, Hitler’s army was met with a cheering crowd throwing flowers at the men, while priests blessed them as they marched. Hitler went so far as to call for a referendum on March 29, 1936, in which the vast majority of Germans had voted in approval of the decision to remilitarize; along with this referendum was the support from most Germans of his direct defiance of the Treaty of Versailles.21 The growth of popularity and nationalism were key contributing factors in Hitler’s decision to remilitarize the Rhineland; however, it was not the only factor. Hitler shared the anger that the German populace had towards the Treaty of Versailles and wanted to challenge not only the Treaty but the Western powers that had forced it upon them.

After taking power in 1933, Hitler had made it clear that he would denounce the Treaty of Versailles on the grounds that it was unfair to the German people.22 As argued by Gordon and Henig, Hitler was interested in challenging the Treaty of Versailles and weakening the nations that imposed it upon them. Knowing that France and Britain were aware of an imminent reoccupation of the Rhineland and that they were not likely to retaliate, Hitler took this as an opportunity to display the weakness of the Treaty and the weakness of the allies for not enforcing it. In taking such an action, Hitler showed the Western powers that he would rather take militaristic action to get what he wanted rather than through political discourse.23 The unwillingness to retaliate against this action opened the door for further violations of the Treaty of Versailles and laid the foundation for the Second World War. Hitler, knowing that he was still in the process of expanding his military, would not have made the decision to remilitarize unless he was confident that the benefits of doing so outweighed any potential risks.

As agreed upon by historians, France was aware of a potential remilitarization of the Rhineland by Germany, but chose not to retaliate or intervene. In his book 1940: The Fall of France, French General André Beaufre acknowledges that upon joining the General Staff, that he was made aware that the French army was not prepared for conflict and the leadership was weak. The French Government asked the General Staff if they were capable of intervening in the Rhineland and combatting the invading German troops. The Staff said they were ill-equipped to combat Germany as it required full mobilization.24 As argued by Shore, Hitler was aware of France’s inability and unwillingness to retaliate, whether it be from Foreign Minister Neurath or from his own intuition, given the declining relationship between France and its allies.19 Hitler’s knowledge of France’s weakness made him confident that he could easily remilitarize the Rhineland and gain the strategic benefits such as growth in popularity and nationalism, challenging the Treaty of Versailles, while simultaneously displaying the weakness of the Western powers, all while maintaining the confidence that his actions would not result in retaliation.

After conducting research on the topic, understanding the arguments made by a variety of historians as well as their reasoning, it is clear that multiple factors contributed directly to the decision to remilitarize. The decision to remilitarize was strategically planned by Adolf Hitler, in defiance of his generals to build on his popularity as the sole reliable leader, weakening other branches of his own government. It also displayed the weaknesses of the Western allies in their ability to enforce the Treaty of Versailles, something that he continued to exploit until war was declared on Germany by the allies in September 1939.

While historians may never know the exact reason as to why Hitler made the decision to remilitarize the Rhineland, there is a consensus that Hitler had clear strategic benefits in mind. The decision to remilitarize will always be a clear contributing factor that pushed Europe towards the Second World War and shape the world for generations.

Adolf Hitler wanted to cement himself as the leader of Germany and strategically planned actions such as the remilitarization to build on popularity among the populace. Hitler fed on the anger of the German people to the Treaty of Versailles, and in the early years of his rule, he challenged the treaty and the alliance that imposed it. Adolf Hitler was aware that his military and his government were not incredibly powerful and did not take risky actions unless there was a guarantee of no retaliation from France. Hitler was extremely successful in this decision, as he benefited greatly from remilitarizing. Not only did Hitler build upon his popularity among the German populace even among non-members of the Nazi party, but he was also capable of weakening France by deteriorating its relationship with neighboring nations. He showed the world that Germany was no longer going to sit idly by while the western powers continued to weaken them, and instead, they were going to become a global power once again, and one that was a force to be reckoned with.

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography (New York, W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 2010): 72, 75-76. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography (New York, W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 2010): 81, 96-97. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography (New York, W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 2010): 127-135,162-163. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography (New York, W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 2010): 190-191,194-195. ↵

- Gordon Craig, Germany 1866-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978): 542-543. ↵

- Larry Eugene Jones, “Hindenburg the Conservative Dilemma in the 1932 Presidential Elections,” German Studies Review 20, no. 2 (1997): 244-245. ↵

- Gordon Craig, Germany 1866-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978): 559-560, 568. ↵

- Gordon Craig, Germany 1866-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978): 571, 573-576. ↵

- Gordon Craig, Germany 1866-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978): 577-578, 589-590. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler Hubris (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 1998): 586-587. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler Hubris (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 1998): 587-588. ↵

- Adolf Hitler and Norman Hepburn Baynes, The Speeches of Adolf Hitler: April 1922-August 1939 (New York: Howard Fertig, Inc., 1969): 308. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: Profiles in Power (London and New York: Pearson Education Limited, 1991): 124. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: Profiles in Power (London and New York: Pearson Education Limited, 1991): 124-125. ↵

- Gordon Craig, Germany 1866-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978): 691. ↵

- Gordon Craig, Germany 1866-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978): 690-691. ↵

- Ruth Henig, The Origins of the Second World War 1933-1941 (London, Routledge, 1985), 40. ↵

- Zach Shore, “Hitler, Intelligence and the Decision to Remilitarize the Rhine,” Journal of Contemporary History 34, no. 1 (1999): 5. ↵

- Zach Shore, “Hitler, Intelligence and the Decision to Remilitarize the Rhine,” Journal of Contemporary History 34, no. 1 (1999): 5-6. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: Profiles in Power (London and New York: Pearson Education Limited, 1991): 124-125. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler Hubris (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 1998), 588-590. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler Hubris (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., 1998): 587. ↵

- Ruth Henig, The Origins of the Second World War 1933-1941 (London, Routledge, 1985), 40-41. ↵

- André Beaufre, 1940: The Fall of France (London, Cassell, 1967), 43. ↵

- Zach Shore, “Hitler, Intelligence and the Decision to Remilitarize the Rhine,” Journal of Contemporary History 34, no. 1 (1999): 5-6. ↵

16 comments

Jaedon E

Great article! Congratulations on your award. It was well-earned! One thing I personally do find interesting is when learning history, seeing how different government operations motives were led and how they wanted to accomplish that is astonishing to me. Hitler being a very iconic and historical game-changer, it is never boring learning about his other attempts within his time of paving his was to the top.

Azeneth Lozano

Congratulations on your well-deserved award. There was a lot of information revealed about Hitler’s plans with Rhineland and his rise to the top. The article gives details as to some of the reasons why Hitler had certain motivations on his path to the top. In addition, the story shows how Hitler manipulated his country into believing and trusting him over everything.

Sydney Nieto

Congratulations on your article. I’ve heard of Hitler but didn’t know that he wanted to remilitarize the Rhineland. By reading this I was surprised to see how Hitler was able to partake in an election after going to prison. This article also showed how smart he was as he got people to weaken their trust in the government and put their trust into him.

Melyna Martinez

This article shows the road of a bit of Hitler’s thinking before World War II, coming to see what lead him to turn on his government. Using things like the Treaty of Versailles to solidify his political power, and used much of his information and resources to show the lengths he would go to. Giving an understanding as to why Hitler wanted to remilitarize the Rhineland, allowing us to understand his background and rise to power.

Eugenio Gonzalez

First of all, congratulations on your winning article. The author does an excellent job telling readers about Hitler’s beginnings in the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). I did not know about this phase of Hitler, where he tried to overthrow the government but failed and was imprisoned. I like how the author talks about Hitler’s motivations for remilitarizing Rhineland.

Brandon Vasquez

This was an amazing article! Hitler’s remilitarization of the Rhineland was one of the biggest decisions he could have made at the time and I agree with you that it was done not only to equal the playing field but also to defy the Treaty of Versailles. If Hitler didn’t remilitarize this part of the country he would in no way have been able to attack the surrounding countries and continue his plans.

Nicholas Quintero

I thought this article was extremely well done. The way sections were broken up and the pacing of the material covered was very easy to follow and interesting. That along with the language that was used was not trying to be overcomplicated or had any issues with redundancy. I also enjoyed part of the open ended aspects, such as not knowing why Hitler did certain things when advised not too, it engages you and makes you reflect and think.

Vianne Beltran

Hi Aaron,

I think your award is well-deserved. It did an excellent job of explaining Hitler’s rise to power and the reasons he made the decisions he did. I think it’s interesting that most people in Germany were interested in remilitarization. It’s no wonder Hitler made the choice to risk it despite disagreement from other higher ups. It clearly was worth it to Hitler and it does seem it worked out in his favor unfortunately.

Katelyn Canales

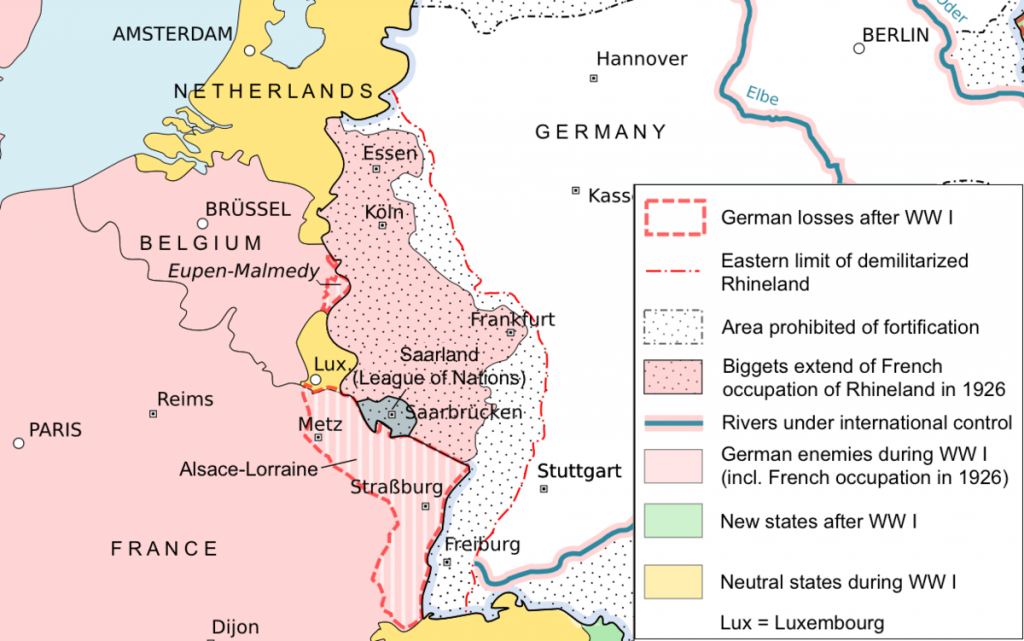

Mr. Sandoval, first I wanted to congratulate you on getting your article published, and getting an award! Congratulations! I was most excited to read your article, because I have always had a fascination with learning the mind of Hitler. A very interesting article, I had never heard of Hitler wanting to remilitarize Rhineland. The story kept me on my toes, escally where we begin to see why we ended up in WW2. I enjoyed looking at the map, the legend was easy to read and gave the article more context. The photo of the map gave me a better understanding of where exactly the story is heading. I can definitely agree with you that Hitler’s popularity as a nationalist, gained him even more of a motive to have a drive to weaken the Western powers. Excellent work! I can’t wait to read/learn more from you in the future!

Phylisha Liscano

A very well-written article and extremely interesting. Before now I had no knowledge of Hilter wanting to remilitarize Rhineland. Your article was detailed and provided many facts. I can tell you did lots of research and I enjoyed getting the chance to read and take a look at the images you provided. Overall interesting topic and good job.