In 58 BCE, Roman proconsul Julius Caesar, a member of the first Triumvirate and an important political figure in the Roman Government, was forced to flee the very city he helped rule. As debts from his political aspirations and a general souring of relations among members of the senate began to catch up with him, an opportunity presented itself.1 To the north of Italy, the massive frontier of modern day France and Belgium provided a persistent thorn in the republic’s side. For years, the tribes of Gaul had descended on Italy, raiding and pillaging. As a land ripe with spoils and slaves, acting hostile to Rome, no better opportunity could be offered to Caesar. If he stayed in Rome, his debts would be called in. Unable to pay them, he’d be cast out of Rome, and his family name would be sullied. But in Gaul, glory in combat and vast new territory awaited him, should he survive.

When Caesar departed for Gaul in March of 58 BCE, he had under his command four veteran legions, all of which had served under him through previous conquests. These men were the best the Roman military could offer, and they pledged themselves and their lives to Caesar.2 As proconsul, Caesar had the ability to raise additional troops should the need arise, and in Gaul, he was able to do so, with the aid of tribes friendly to Rome.3

As the legions moved into Gaul, they faced very unorganized resistance. The tribes of the Gauls were nomadic and proud peoples, with long and complex histories. Facing invasion from an enemy much more organized and well trained, the tribes would not organize to form any sort of coalition against the Romans. This gave Caesar several victories early into the conquest at little cost to his own forces. Supply trains ran unhindered to the front line, since there was no one left alive to harass them. The Romans, under Caesar, conducted total war on the peoples of the Gaul. Villages burned. Men killed. Women and children, enslaved. This was the fate that awaited any tribe proud enough to stand against the might of Rome. As news spread of Caesar’s victories, some tribes pledged fealty to Rome in return for being spared by the legions. The divisions among the tribes, whether they were long standing or trivial disagreements, made subjugating Gaul a task that was much easier than expected.4

By 52 BCE, a fair swath of Gaul had been brought under Roman control. As complete and total domination loomed over the remaining tribes, one among them finally sought to organize a revolt against Caesar. Vercingetorix, chieftain of the Arverni people, began to reach out to the tribes who were still unconquered. Through these alliances, Vercingetorix became the supreme commander of the united Gaulic forces, leading some of his men to refer to him as their king. Vercingetorix began a scorched earth campaign against Caesar. What the Gauls lacked in military tactics, they made up for in knowledge of the land. As the legions moved forward, expanding the front of the war, the Gauls would burn their own fields and villages, leaving no prize to be taken by Caesar, and more importantly, no food or supplies to sustain his legions.5

As supply lines with Rome became longer and longer the deeper he progressed into Gaul, and with every tribe either destroyed or subjugated and having all their supplies seized to fuel the war, Caesar was put in a situation he had not anticipated. However, he did not have many options. If he returned to Rome now, then Vercingetorix and his united forces would reclaim all the land Caesar had conquered thus far, rendering the conquest a complete failure, which would make Caesar look incompetent. If he continued to push forward, he risked alienating his legionaries by forcing them to endure conditions and rations they could not continue on. A gambit was placed in front of Caesar, and he chose to evoke the latter option.6

The Roman war machine marched on. In its path lied the capital of Vercingetorix’s tribe, Avaricum. Following his tactics thus far, Vercingetorix intended to raze the city to prevent the Romans from resupplying from it. The citizens pleaded with Vercingetorix to spare the city, and since the city had strong defenses and a decent garrison, he decided to leave the city to defend itself.7 This would prove to be a fatal mistake. For a grueling twenty-five days, Caesar’s men besieged the city, building siege towers and artillery to breach the city. The legionaries, starving from a lack of supplies, used their situation as motivation to take the city. Their lives, and Caesar’s conquest, quite literally depended on taking Avaricum.8

Victorious from the siege, Caesar next marched his resupplied and fed legion to the city of Gregoria. However, Vercingetorix was lying in wait. Using the days Caesar spent sieging Avaricum, he was able to burn every bridge in the area as well as raise a cavalry to use against the legions. The Romans were not prepared for this level of organized resistance. The Gauls held the high ground surrounding the city and could easily survive a siege if Caesar ordered it. Rather than retreat and muster more troops with more supplies, Caesar ordered his forces to push forward, thinking the brute force of his legions would frighten the Gauls into a retreat. This miscalculation and resulting blood bath left Caesar’s legions in disarray. In his commentaries on the battle, Caesar states that he lost at least forty-six centurions and some seven hundred legionaries, though these numbers are likely much higher.9 Caesar regrouped the surviving legionaries and retreated into friendly territory. Although the victory was a huge moral boost to the Gauls, it would not be enough to stop Caesar.

Following the disaster at Gregoria, Caesar regrouped with his Gaulic allies to resupply and levy more soldiers to fight for him, including a cavalry composed of Gauls from loyal tribes.10 With his legions’ strength brought back up, Vercingetorix faced fighting Caesar at a major disadvantage in open combat. Roman legions alone were quite fearsome, but reinforced with a fully equipped cavalry made them the dominant force on the battlefield. Rather than continue his scorched earth campaign, he decided to garrison his troops in the fortified city of Alesia. From here, Vercingetorix called out to his remaining allies to muster a relief army to reinforce him. When Caesar later arrived to meet the enemy, his options were limited. Rather than chance a direct assault, he ordered his men to encamp around the city and blockade Alesia. The legionaries built a massive wall around Alesia known as a circumvallation to prevent any reinforcements or supplies to be delivered to the city. Vercingetorix was effectively cut off from the rest of the world and was forced to immediately issue rationing orders to his men and the civilians in Alesia if they had any hope of outlasting the siege.11

As completion of Roman defenses were completed, captured scouts and deserters of Vercingetorix’s army informed the Romans that a massive relief army was marching towards Alesia. Knowing that his troops faced an insurmountable disadvantage being encamped against a wall in open combat against a larger force, Caesar ordered the construction of another wall. This wall, a contravallation, was built to withstand a siege from the approaching relief army.12 Essentially, the besiegers had now become the besieged. With the contravallation completely encasing the Romans, they cut themselves off from resupply and were forced into one of the most curious military engagements in history.13

Finally, the day had come for the Battle of Alesia. Once the relief army had appeared, Vercingetorix ordered his men to attack Caesar’s fortifications at the inner wall. As they attacked one wall, the relief army mounted an assault on the other wall. The legions were ordered to hold weak points and rain arrows down on the assaulting relief forces. In preparation of the relief army being larger than his own forces, Caesar ordered his Gaulic cavalry to encamp away from the main body of legionaries on another portion of the Roman encampment, in the rear flank of the Gauls. As the fighting grew closer into the Roman lines, with parts of the outer wall beginning to falter, Caesar himself joined the fray. He issued an order for the cavalry to attack the relief army as a diversion to give the legionaries an opportunity to push back the Gauls. The cavalry caught the Gauls off guard and from behind, decimating the relief army, and breaking their ranks in a hasty retreat, fearing a larger Roman relief army to arrive at any moment. Caesar’s gambit paid off and is remembered today as one of the most daring military maneuvers in all of military history. If it had failed, Caesar and his men would have surely been defeated at Alesia.14

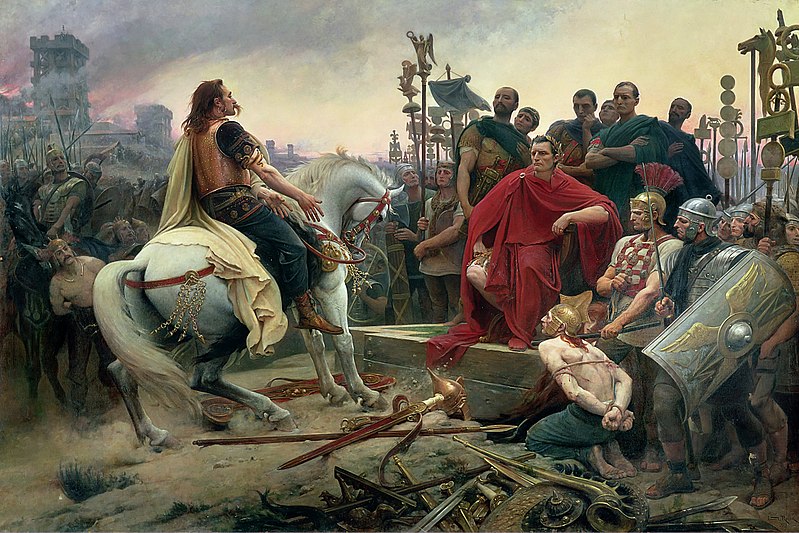

With the relief army dispersed, Vercingetorix had no options left. During the siege, all their supplies had been consumed. They did not anticipate Caesar to actually survive the relief army’s push. Faced with starvation if they continued to hold out and facing grim retribution if they pushed against the Romans in an effort to hold Alesia, capitulation was the only resort. Caesar issued demands for the leaders of Alesia and the Gaulic army to surrender themselves or face his wrath. The Gauls complied, and Vercingetorix surrendered to Caesar, thus ending the Conquest of Gaul.15

Following the victory at Alesia, those who opposed Caesar were killed or made slaves. Many women were given to legionaries as wives for their service. Vercingetorix was imprisoned for years following his defeat, until his death during Caesar’s triumph in a public execution. Caesar himself would be talked of with both praise and contempt in Rome. To the citizens, he was the conquering hero who tamed the wild Gaul and brought Roman civilization to the frontier. To the senate, he was a threat to the very existence of the republic. A man with that much popularity with the people and his legionaries, coupled with a vendetta with those who forced him to conquer Gaul in the first place was not something the senators could not allow. They ordered Caesar back to Rome to face trial for engaging in a conquest raised with Roman soldiers and the Roman banner illegally–alone. Caesar, rather, defied the senate instead, and crossed the Rubicon River with his soldiers two years after the Battle of Alesia. This act signaled the start of the Second Roman Civil War, marking the beginning of the end of the Roman Republic.16

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Julius Caesar.” ↵

- Gaius Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul (Penguin Classics, 1983), Book 1, Chapters 40 and 41 ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Julius Caesar.” ↵

- The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome. 2002, s.v. “Gaul,” by Don Nardo. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Vercingetorix.” ↵

- Gaius Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul (Penguin Classics, 1983), Book 7, Chapter 10. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Vercingetorix.” ↵

- Gaius Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul (Penguin Classics, 1983), Book 7, Chapters 16-28. ↵

- Gaius Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul (Penguin Classics, 1983), Book 7, Chapter 51. ↵

- Gaius Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul (Penguin Classics, 1983), Book 7, Chapter 56. ↵

- The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, 2002, s.v. “Siege of Alesia,” by Don Nardo; The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, 2002, s.v. “Battlefield Tactics,” by Don Nardo. ↵

- The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, 2002, s.v. “Battlefield Tactics,” by Don Nardo. ↵

- The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, 2002, s.v. “Siege of Alesia,” by Don Nardo. ↵

- The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, 2002, s.v. “Siege of Alesia,” by Don Nardo. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Vercingetorix;” The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, 2002, s.v. “Siege of Alesia,” by Don Nardo. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Julius Caesar.” ↵

88 comments

Kimberly Parker

The images used in this article helped paint a clearer image of what was going on. This article does a great job delving into Julius Caesars’ life and his relationship with the Roman Empire. Before reading this, the only thing I had really known about his was that he was assassinated and that he was a good military leader. But him fleeing from Rome because he was scared people were looking for political payment makes him look like a coward.

Vanessa Quetzeri

I never knew much about Julias Caesar but I have heard his name being mentioned before. It is impressive that someone could have so much power or such a large impact on people, that eventually became his followers. His militia was very organized and incredibly smart with their tactics, which then lead to Caesar’s success and the surrender of Vercingetorix.

Paul Garza

Before this article I did not know much or anything about Julius caesar except that he was stabbed to death by roman senators. Very interesting article that really goes deep into Caesars life and his relationship with the Roman Empire. I find it fascinating that caesar had such an impact on the people of Rome and his militaries that when he fled to Gaul they were loyal to him and were willing to follow him, even if it meant persecution by the Roman Empire. I also found interesting that caesar and his militia were so tactful and successful that Vercingetorix was struck with fear and ended up surrendering.

Michael Thompson

I really didn’t know what led up to the contempt that made the senators kill Julius Caesar, other than the obvious fact that he declared himself dictator for life, which they obviously hated. But the fact that he was able to save his role with the republic and have such a strong role came from this makes sense, as it was an obviously strong military battle for Caesar, making him look extra competent to rule.

Margaret Maguire

I knew a little bit about Julius Caesar before reading this article because I took Latin in high school but I had no idea that he fled from Rome because he was scared of people looking for political payment. He fled to Gaul with four legions and picked up more men on the way as needed. I knew that Romans fought very orderly and organized but I did not know that because of this, they won many battles against barbaric tribes while going to Gaul. This was a really neat article

Analisa Cervantes

In high school I learned about Caesar and his conquests for Rome and of the Letters he wrote. Before now I only had a general knowledge of his conquest in Gaul. Learning more about the Battle of Alesia and how Caesar defeated Vercingetorix’s forces is interesting. However this only seemed to seal both his fate and the fate of the Roman Republic.

Todd Brauckmiller

The only time I had herd of Caesar was when he was brutally stabbed to death. When hearing about the battle of Alesia I now have more knowledge of what Caesar actually did. Taking the Roman soldiers to fight really reminds me of Leonidas and his 300 warriors. Though it wasn’t technically legal but he did win the battle and became a hero for his people, doing what he though was right. The question of weather or not he should have been killed is something that would require more in depth reading and research. Enjoyed reading the article and I hope to find more like it in the future.

Gabriel Lopez

It’s crazy to learn that Caesar was so powerful that Vercingetorix had to burn his own villages just so Caesar couldn’t take it. It was fun to read how strategic Caesar was and how he did not give up after he mistakenly made an overconfident decision. I also really like the map that was provided since I had trouble picturing the multiple walls, so it made the article easier to understand. Great article overall.

Jake Mares

The snapshot into the minds of these military leaders gives an extraordinary view of originally unseen issues during war. The “counterplay” between the leaders dealing with the bombardment and then the relief army is something not highlighted much in many history books. Also, Caesar’s predicament between looking incompetent and losing much of his force gives a clear view of his priorities despite coming out victorious.

Amanda Quiroz

What a great article! I never heard of this battle before and it was interesting to read about Caesar and his determination for victories as he led the Romans. It’s interesting because people either praised Caesar or despised him for his conquest. The map also helped me be able to visualize the battle.