The earth is dying, and it is our fault. We are currently living in the midst of the sixth mass extinction event–the Holocene extinction.1 The last case of such extinction was 65 million years ago when an asteroid destroyed 76 percent of all species on the planet, including the dinosaurs. However, this time, there is no giant space rock hurtling towards us that we can cast all of our blame onto. “For the first time in the history of life on Earth, one species is killing countless others. For the first time, one species, Homo sapiens–that’s us–is waging a war against nature.”2 We are doing so both intentionally and unintentionally, but our ignorance cannot be an excuse. Moral consequentialism can explain that, in this case, the purpose of our actions does not matter as much as the result of them, and the result is dozens of species going extinct every single day.

As Aldo Leopold says, “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.”3 It is true, this world has many wounds, and The Wildlands Project has compiled a list of the seven primary ecological wounds to the land. These include the direct killing of species, loss and degradation of ecosystems, fragmentation of wildlife habitat, loss and disruption of natural processes, invasion by exotic species and diseases, poisoning of land, air, water, and wildlife, and global climate change.4 Humans are doing all of these things. We are torching the Amazon rainforest to clear it for cattle and farming, tossing explosives into the oceans to wipe out large schools of fish all at once, and throwing away 2.5 million plastic water bottles every hour. In short, the actions of humans are killing the earth and all species that inhabit it. Thankfully, the actions of humans can also save the earth, and rewilders seek to do just that.

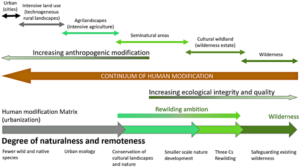

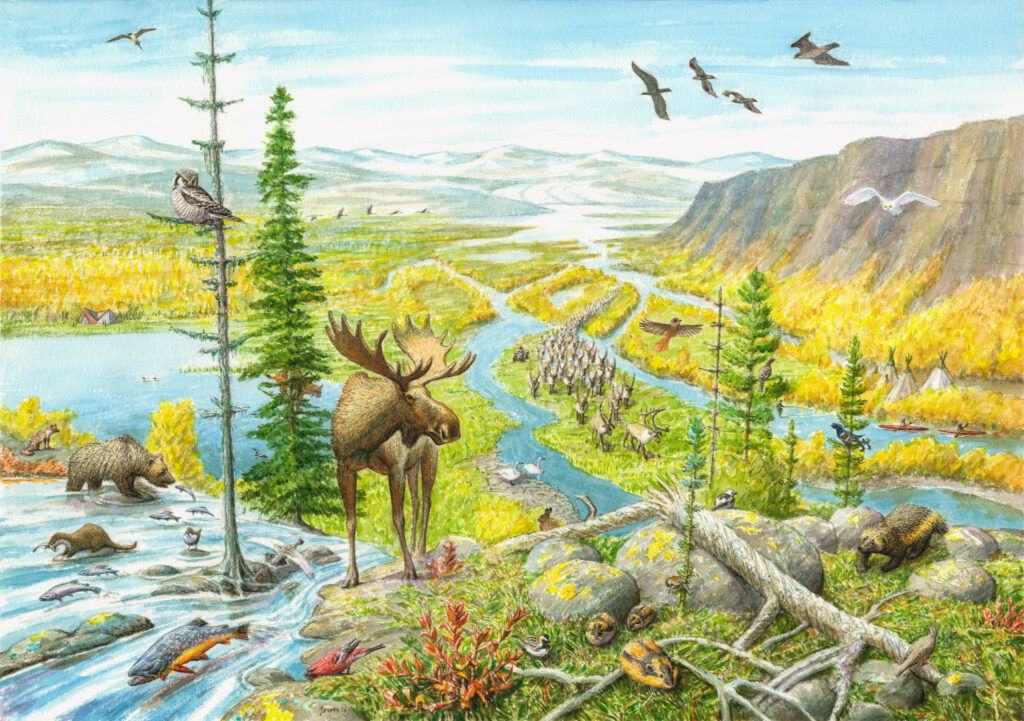

Sir David Attenborough says, “To restore stability to our planet, we must restore its biodiversity, the very thing we have removed. It is the only way out of this crisis that we ourselves have created. We must rewild the world.”5 Rewilding is a relatively new idea to conservation that has been picking up speed recently, especially in Europe. As it is still finding its footing, there are many definitions circulating. One such definition comes from Boitani and Linnell, who claim, “rewilding is the passive management of ecological succession with the goal of restoring natural ecosystem processes and reducing human control of landscapes.”6 Soulé and Noss describe it as “the scientific argument for restoring big wilderness based on the regulatory roles of large predators.”7 Jepson and Blythe say rewilding “refers to ‘spaces of innovation’ in conservation philosophy, science, and management, characterized by a desire to restore ecosystem processes at various scales, often through the introduction of functional species and restoration of natural disturbance and dispersal”8 The Society for Conservation Biology recognized that there was a limited utility of rewilding due to confusion over the lack of a solid definition, so they surveyed 59 rewilding experts, held workshops with people from all around the world, and did an extensive literature review to create this unifying definition:

Rewilding is the process of rebuilding, following major human disturbance, a natural ecosystem by restoring natural processes and the complete or near complete food web at all trophic levels as a self-sustaining and resilient ecosystem with biota that would have been present had the disturbance not occurred. This will involve a paradigm shift in the relationship between humans and nature. The ultimate goal of rewilding is the restoration of functioning native ecosystems containing the full range of species at all trophic levels while reducing human control and pressures. Rewilded ecosystems should–where possible–be self-sustaining.9

That being said, many rewilders do not want to give the term a definition at all. They share a fear of becoming too constrained; of having policy-makers telling them what they can and cannot do, and limiting their innovation. To complicate matters further, rewilding varies geographically.10 North American rewilding focuses more on recreating the past and heavily involves carnivores, whereas European rewilding is future-orientated and centered around grazers. So far, four different types of rewilding have been identified: trophic, paleo, translocation, and passive.

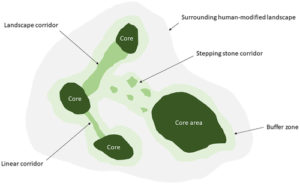

Trophic rewilding introduces species to an area with the goal of restoring top-down food chain interactions. It is commonly referred to as the “three C’s,” or cores, corridors, and carnivores.11 “Cores” pertains to protected areas of land. However, most cores are too small to effectively preserve biodiversity, so corridors must be established between them in order to reduce wildlife isolation. If you want to practice profound conservation in a continent, you have to do it at the scale of that continent. Large carnivores are the last piece of the puzzle. They are the key to keeping the ecosystem healthy by regulating other predators and prey. Without them, nature does not seem as natural, and the wilderness does not seem as wild. The poster child for tropic rewilding is Yellowstone National Park.

When people started to raise livestock in the United States, many ranchers set out to kill natural grazers, such as elk, because they saw them as competition for their herds.12 This decline in prey forced wolves to turn to the livestock as a food source, frequently attacking farms. As the public’s fear increased, farmers and ranchers started a war against the wolves. They were baited and trapped, poisoned and shot. Within a mere 40 years, 100,000 wolves were killed in Montana and Wyoming alone. 13 Humans were easily victorious in this one-sided war. Even the National Park Service pitched in to help, exterminating all of the wolves from Yellowstone by the 1930s.14 However, as researchers started to see the detrimental effects that the loss of these animals was having on the ecosystem, public opinion began to shift. As a result, wolves were added to the endangered animals list in 1967.15 Since then, there have been a few plans to reintroduce wolves to their original habitats, but one, in particular, stands out. After an extensive four-year study, 31 wolves from Canada were captured and released into Yellowstone National Park in 1995.

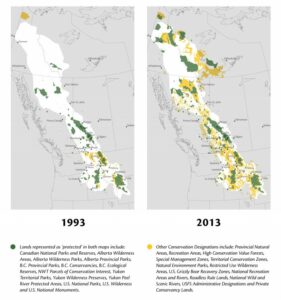

This action had conservationists rejoicing, but ranchers were shaking in their boots with fury. The plight of the ranchers cannot be completely disregarded, but the science is undeniable. Wolves have been the catalyst for ecosystem revival, and their reintroduction has even affected species that are seemingly unrelated to them, such as beavers.16 Without wolves, elk no longer had to be vigilant. They could relax, moving lackadaisically from place to place. This caused overgrazing, especially in places that used to be dangerous for them, such as the river. The elk’s new habits decimated the willow population there, leaving riverbanks barren. The absence of shrubs and trees meant that there was no material for beavers to build their dams, causing the population to leave. When wolves came back, elk had to be vigilant again, allowing plant life to recover and prompting the return of beavers. The wolf population has been steadily increasing, and so have complaints from ranchers and hunters. Wolves do not understand the boundaries of protected areas and have been known to visit a farm or two. The government and some wildlife conservation groups have offered compensation for wolf-related casualties of livestock, but that is unsustainable.17 This is where the corridors element of trophic rewilding comes in. A safe passageway through habitats is a necessity for larger animals, such as the wolf.18 The Yellowstone to Yukon (or Y2Y) initiative is working on just that. Beginning in 1993, Y2Y has been working on acquiring and protecting the 2,100 miles of sparsely populated land between Yellowstone National Park in the United States and the Yukon region in Canada by prohibiting road projects and other developments that would interfere with the habitat and movement of wildlife.19 Over 460 groups have joined the cause, from landowners to businesses to Indigenous tribes.20 As of 2023, 80 percent of the land has been conserved.21

Another type of rewilding is paleo, which refers to the desire to restore the ecosystem to what it was pre-civilization, including the megafauna that existed at the time. 22 One of the first widely recognized rewilding projects, Oostvaadersplassen (from here on to be referred to as OVP), stemmed from this now fundamental idea of rewilding.

The foundation of OVP was laid when a piece of man-made land intended for industrialization was abandoned in the 1970s.23 The deserted land quickly sprouted reed marsh and willow scrub, which attracted a multitude of geese. The habits of the geese shaped the ecosystem, and soon wetland pools were born, attracting even more bird species. By 1983, OVP was designated as a nature reserve, put under the jurisdiction of the Staatsbosbeheer, the state forest agency (from here on to be referred to as SBB).24 However, forest succession was hot on the tails of the open area, and ecologists worried that tree saplings the geese could not eat would soon take over the grasslands. Luckily, biologist Frans Vera had an idea to reintroduce extinct species that played the crucial role of grazing. Of course, they did not have the technology for that, so they brought in the next best thing: cattle and horses. It was a great success, and around 10 years later they introduced deer as well. OVP lies in a densely populated area, just 20 miles from Amsterdam, so SBB decided to fence it in when they added these animals, a decision that would later prove fatal to the project. In order to follow rewilding ethos, SBB kept a hands-off approach to the management of the wildlife, causing the animal population to rapidly grow to over 5000 individual animals.25 This number would rise and fall due to harsh winters and food scarcity. These natural processes can be hard for people to witness, and concerned citizens started to protest OVP. SBB accepted a policy to cap populations by culling animals they believed would not survive anyways.26 After a particularly harsh winter in 2018, in which more than 60 percent of grazers were shot to prevent further suffering, the public was outraged, and activists responded by trespassing and illegally throwing bales of hay over the fences.27

In the height of the chaos, newspapers were printing photos of starving animals with headlines comparing OVP to a concentration camp. Since the area was fenced in, people argued that they were “kept” animals, not “wild” animals, so SBB should be required to feed them.28 These protests led to new policies, such as the relocation of animals, creation of shelters, and bringing in veterinary support.29 This was a win for animal welfare advocates, but a giant step back for rewilders, who considered OVP to now just be a glorified zoo. New OVP officials are working hard to repair its public image and boast about no animal having died from starvation in the last three years.30 They are shying away from letting nature run its course and instead making nature themselves by experimenting with human impact on the land. Multiple projects have been taken on by the rangers to completely control OVP, such as dividing it into blocks that each have a different habitat (grassland, marshland, woodland, etc), changing water levels to create wet and dry times, creating pools, and planting trees.31 OVP was a milestone for rewilding in its early stages, however, by the definition discussed earlier, it can no longer be considered a rewilding site. In fact, rewilders have alienated themselves from the project, Frans Vera himself even condemned current management strategies.32 To no surprise, OVP has also distanced itself from the concept of rewilding, instead calling the project “nature development.”33

A current example of paleo rewilding is the aptly named Pleistocene Park. Here, in a remote area of Siberia, researchers are attempting to re-create the ecosystem as it existed over ten thousand years ago during the Pleistocene epoch.34 Not only are they trying to produce the same plant life, but the same animals as well, including the extinct wooly mammoth. Many scientists believed these mammoths went extinct due to climate change, but the leader of the project, Sergey Zimov, has a different hypothesis. He believes that they survived the rapid temperature shifts only to be hunted down by humans.35 They are currently working to clone the wooly mammoth. Scientists have extracted preserved DNA from fossils and are working on editing the genes. If a successful embryo is created, they will place it into an elephant. The work started in 2021, and was given an additional 60 million dollars in funding in 2022. As of 2023, the company in charge has stated that de-extinction will happen by 2027.36 However, other scientists are skeptical. A group from the University of Copenhagen tried to bring back an extinct rat and found it much more challenging than expected. After everything, they were still missing 5 percent of the rat’s genome.37 To put that into perspective, human genomes only differ from chimps by 1 percent. Either way, Pleistocene Park is still a huge success. Scientists have replanted grasses, mosses, and lichens from the Pleistocene epoch, encouraged the restoration of permafrost by digging deep caves, and reintroduced similar animals to those that have gone extinct, such as elk, bison, and musk ox.38 They are excited about how well these techniques are working to combat climate change. Permafrost is a remarkable carbon reservoir, and grasses absorb and store greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere.39

Next, there is translocation rewilding, which occurs when the restoration of dysfunctional ecosystems is accomplished through species reintroduction.40 A good example of this is happening in the Galapagos islands. There, more than 9 thousand giant tortoises have been released into the wild.41 Their consumption of vegetation leads to seed dispersal, which is vital to keeping the ecosystem healthy. Although wildly successful so far, the project still has a long way to go, as the tortoise population is still only 10 percent of what it used to be, and they occupy only 35 percent of the available habitat.42 Madagascar has implemented a similar project, reintroducing Aldabra giant tortoises from a nearby island that are both genetically and aesthetically similar to the original Madagascan giant tortoises that have gone extinct.43 This is especially important for the plant species in Madagascar, which have evolved to grow spines and multiple leaf shapes to defend themselves from hungry herbivores. Without the tortoises, those traits would disappear.44

It is also important to analyze the practice of covert rewilding– the arguably hilarious subgenre of translocation rewilding. Covert rewilding is when a species is translocated in secret and/or illegally because the project was denied official permission.45 In 1996, Tasmanian devils were released into Australia in three precisely planned locations, allowing them to remain undetected for years until the population was big enough that an attempt to eradicate them would prove to be counterproductive.46 The wildlife vigilantes that executed this plan remain unknown. In 2007, “beaver bombers” released beavers in the United Kingdom after the request to reintroduce them was protested by farmers and shot down by the government.47

Finally, passive rewilding refers to when human control of landscapes is limited or nonexistent. This is the end goal of rewilding projects.48 Richard Bunting states this objective plainly in his definition of rewilding, calling it “the large-scale restoration of ecosystems to the point where nature can take care of itself.”49 Bunting is a spokesperson for the Scottish Rewilding Association, which is a collaboration of 20 rewilding organizations. He is currently pushing for Scotland to become the first-ever rewilding nation and has set a lofty goal of 30 percent of the land being rewilded by 2030.50 Scotland is doing well so far, with three large rewilding projects currently enacting big changes: Carrifran Wildwood, Mar Lodge, and Cairngorms Connect, which all focus on removing invasive trees and replacing them with native species. Mar Lodge is the most extensive, at over 37 thousand acres.51 The whole of the United Kingdom is home to over 80 other smaller rewilding initiatives as well.52

Ultimately, rewilding can mean many different things to different people, but the chief objective of rewilding is to make progress. The fact that this movement has been picking up speed lately is evidence of a human desire to compensate for past mistakes. There are even people rewilding in their own neighborhoods. Residents of a suburban block in Melbourne Australia have turned their yards into gardens, growing 2 thousand dollars worth of edible plants per year.53 They have recently added bird baths and even a pond for frogs and dragonflies. If everyone took on such projects at the local level, then the state of the world would be drastically different. At the end of the day, we as individuals must choose to act. We have the power to change the world through rewilding.

- Josephine Campbell. “Holocene Extinction.” Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science, 2020. ↵

- Dave Foreman. Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century. Island Press, 2004. ↵

- Dave Foreman. Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century. Island Press, 2004. ↵

- Dave Foreman. Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century. Island Press, 2004. ↵

- “What Is Rewilding?” Wild World Rewilding, 2022. ↵

- Luigi Boitani & John D. C. Linnell. Rewilding European Landscapes. Springer. 2015 ↵

- Dave Foreman. Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century. Island Press, 2004. ↵

- Cain Blythe & Paul Jepson Rewilding: The Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery. Icon Books Ltd. 2020. ↵

- Carver, Steve, Convery, Ian, Hawkins, Sally, Beyers, Rene, Eagle, Adam, Kun, Zoltan, Maanen, Erwin V. et al. “Guiding principles for rewilding.” Conservation Biology 35, no. 6, 2021. ↵

- George Holmes, Kate Marriott, Charlie Briggs, and Sophie Wynne-Jones. “What Is Rewilding, How Should It Be Done, and Why? A Q-Method Study of the Views Held by European Rewilding Advocates.” Conservation & Society 18, no. 2, 2020 ↵

- Dave Foreman. Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century. Island Press, 2004. ↵

- Caroline Fraser. Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution. Metropolitan Books. 2009. ↵

- “Wolves in Yellowstone Park,” PBS (Public Broadcasting Service). ↵

- Michael Wilton. “Wolves in U.S. Parks.” Salem Press Encyclopedia. 2019. ↵

- Michael Wilton. “Wolves in U.S. Parks.” Salem Press Encyclopedia. 2019. ↵

- Caroline Fraser. Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution. Metropolitan Books. 2009. ↵

- Michael Wilton. “Wolves in U.S. Parks.” Salem Press Encyclopedia. 2019. ↵

- Caroline Fraser. Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution. Metropolitan Books. 2009. ↵

- Charles C. Chester. “Yellowstone to Yukon: Transborder Conservation across a Vast International Landscape.” Environmental Science and Policy 49. 2015. ↵

- Jodi Hilty. “Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y): Connecting and Protecting One the of the Most Intact Mountain Ecosystems.” Conservation Corridor, 2022. ↵

- “Establishing Wildlife Corridors & Habitat Protections in US & Ca: Y2Y.” Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. 2023. ↵

- Helen N. Kopnina, Simon R. B. Leadbeater, and Paul Cryer. “Learning to Rewild: Examining the Failed Case of the Dutch ‘New Wilderness’ Oostvaardersplassen.” IJW, 2020. ↵

- David Schwartz “European Experiments in Rewilding: Oostvaardersplassen.” Rewilding Org. 2021. ↵

- David Schwartz “European Experiments in Rewilding: Oostvaardersplassen.” Rewilding Org. 2021. ↵

- David Schwartz “European Experiments in Rewilding: Oostvaardersplassen.” Rewilding Org. 2021. ↵

- David Schwartz “European Experiments in Rewilding: Oostvaardersplassen.” Rewilding Org. 2021. ↵

- Helen N. Kopnina, Simon R. B. Leadbeater, and Paul Cryer. “Learning to Rewild: Examining the Failed Case of the Dutch ‘New Wilderness’ Oostvaardersplassen.” IJW, 2020. ↵

- Bert Theunissen. “The Oostvaardersplassen Fiasco.” Isis. 2019. ↵

- David Schwartz “European Experiments in Rewilding: Oostvaardersplassen.” Rewilding Org. 2021. ↵

- Pheobe Weston. “’We Make Nature Here’: Pioneering Dutch Project Repairs Image after Outcry over Starving Animals.” The Guardian. 2022. ↵

- Pheobe Weston. “’We Make Nature Here’: Pioneering Dutch Project Repairs Image after Outcry over Starving Animals.” The Guardian. 2022. ↵

- Pheobe Weston. “’We Make Nature Here’: Pioneering Dutch Project Repairs Image after Outcry over Starving Animals.” The Guardian. 2022. ↵

- Pheobe Weston. “’We Make Nature Here’: Pioneering Dutch Project Repairs Image after Outcry over Starving Animals.” The Guardian. 2022. ↵

- Janine Ungvarsky “Pleistocene Park.” Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science. 2023 ↵

- Sergey A. Zimov “Pleistocene Park: Return of the Mammoth’s Ecosystem.” Science. 2005. ↵

- Tim Newcomb. “Scientists Are Reincarnating the Woolly Mammoth to Return in 4 Years.” Popular Mechanics. 2023. ↵

- Elizabeth Pennisi. “Bringing Back the Woolly Mammoth and Other Extinct Creatures May Be Impossible.” Science org. 2022. ↵

- Sergey A. Zimov “Pleistocene Park: Return of the Mammoth’s Ecosystem.” Science. 2005. ↵

- Sergey Zimov. “Scientific Background.” Pleistocene Park. 2023 ↵

- Paul Jepson. Rewilding: The Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery. Icon Books Ltd. 2020. ↵

- “Rewilding Giant Tortoises.” Galápagos Conservancy. 2022. ↵

- “Rewilding Giant Tortoises.” Galápagos Conservancy. 2022. ↵

- Crystal Gammon. “Rewilding Giant Tortoises in Madagascar.” Rewilding Earth. 2013. ↵

- Crystal Gammon. “Rewilding Giant Tortoises in Madagascar.” Rewilding Earth. 2013. ↵

- Micheal Bode. “Covert Rewilding of Tasmanian Devils to the Australian Mainland May Remain Undetectable for Years.” Phys.org. 2021. ↵

- Micheal Bode. “Covert Rewilding of Tasmanian Devils to the Australian Mainland May Remain Undetectable for Years.” Phys.org. 2021. ↵

- Michael Bode. “Covert Rewilding: Modelling the Detection of an Unofficial Translocation of Tasmanian Devils to the Australian Mainland.” Conservation Letters 14. 2021. ↵

- Paul Jepson. Rewilding: The Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery. Icon Books Ltd. 2020. ↵

- “A Call for the World’s First Rewilding Nation.” Earth Island Journal. 2021. ↵

- Jonathan Shipley. “A Call for the World’s First Rewilding Nation.” Earth Island Journal. 2021. ↵

- “Mar Lodge Rewilding Project.” Rewilding Britain, 2023. ↵

- “Rewilding Projects and Local Groups” Rewilding Britain. 2023. ↵

- Claire Dunn. “Getting Back to Nature: Rewilding in the City.” ReNew: Technology for a Sustainable Future, no. 136 2016 ↵

14 comments

addison

I love the dichotomous perspective that shows how humans choose to act in destructive ways, but can also choose to act in productive ways. It is so easy to think these problems will just solve themselves, or be worked on by someone else, but it is essential for individuals to commit to making good choices for this planet. There is a considerable need to realize that we as people can make the right choice and find ways to let nature shine in places it has been beaten down.

Emilee Luera

This essay is quite informative. I’d never heard of “covert rewilding” before, and the way it’s used makes sense. What an incredible accomplishment. I’d have thought that those who employ this strategy. It will be fascinating to see how rewilding develops as we go toward lifestyles.To some extent, this contradicts our own modern needs, but I can see how it may foster the growth of many ecosystems while still safeguarding what we have left.

Xavier Bohorquez

One of the best interpretations I’ve read on this topic. It will be interesting to see the shift in rewilding some specific species and I hope we can grow our environments in a healthier way. This pushes our own modern ideals to an extent but I can see how this can benefit the development of many ecosystems and conserve what we have left. Glad you won an award on this and I hope I can read more from you in the future!

Maya Naik

Wow, this article is incredibly informative! Your use of sources is impressive and I had never heard of covert rewilding before reading this piece. It’s fascinating to learn about. Those who practice this method must have a true passion for rewilding. I also appreciate the relevant and beautiful graphics that were included in the article. Great job!

Carina Martinez

I loved the beginning, you did not hold back. It was a great hook as well. I’m glad you shed light on this issue. Congratulations on your award!

Analyssa Garcia

Hi Tabitha,

Congratulations on your nomination for Best in Environmental Science! It is clearly well deserved. I really enjoyed reading about this and was fascinated by learning about the various ways of rewilding. This is truly such an important topic/issue and what’s cool is that many urban Econ development groups are aiming for more greenery and planting for new ecosystems. Wonderful job.

Illeana Molina

Congratulations on your nomination! Does help me to gain knowledge about topics I might not be familiar with. I love your imagery, and your title did have me hooked to then keep reading. This article is quite informative. The citations and references were admirable and I like rewilding as a hook and in the title. Environmental Education is an important topic and I look forward to seeing more.

Fernando Milian

This exciting article has reminded me of many concepts I learned in Environmental Science class. If one thing I learned when taking that course is that each species plays a crucial role in the ecosystem. Your text contains that essence and so many other notions of equal importance. As you well explain in this well-written article, rewilding the world is crucial for preserving biodiversity, restoring ecosystems, and, more urgently, mitigating climate change. Great article, and congratulation on your well deserved award!

Carollann Serafin

This by far is the most informative piece that I have read that really informs us about Environmental Education. The use of length and images but majority just speaking on your personal opinion really helped to grasp more of an understanding and insight on the topic. It should really help benefit the earth specially since its starting to decrease in staying alive.

Abbey Stiffler

Congratulations on your article’s nomination! This article is very educational. I had never heard of “covert rewilding” before I read this piece. All of the images you used were excellent, and they were both useful and attractive to look at. Those who use this technique definitely have a love for rewilding. As we progress towards lifestyles, it will be interesting to see how rewilding changes.