April 7, 2024

Rewilding North America: The Disconnect Between Policies and the Environment and Why it’s Destructive

Imagine a world devoid of nature, wildlife, plants, and greenery, virtually a barren wasteland. That is a possible future for our world if we continue to diminish the resources and landscapes that we have by also making it difficult for future generations to protect what is left. In a culture of doom and gloom, it is easy to wave the white flag and give up; however, critical movements such as rewilding, advocate conservation, restoration, and hope for a greener and brighter future. The only way this can be achieved is if the political world and scientific community remain in constant communication and collaboration to provide the best possible conditions for nature to thrive and persevere. The concept of rewilding is to rebuild wildlife diversity and abundance and giving natural processes the opportunity to enhance ecosystem resilience, with enough space to allow nature to drive the changes and shape the living systems.¹We know this is possible because rewilding in Europe has taken many shapes and forms that have allowed people to see how nature has prospered and the measures taken place to protect that prosperity. Rewilding is not a common term or practice in North America as it is primarily used in the European concept; in the United States specifically we are more familiar with the three C’s which are Cores, Corridors, and Carnivores. The 3 Cs encompass a rewilding initiative that aims to increase biodiversity, reverse extinction trends, and revive ecological machinery to mitigate climate change.² The process is completed by identifying a large area, or core, in need of ecological restoration, implementing a passage for animals way that effectively connects two, or more cores,

and finally, including the presence of carnivores which revive the ecosystem by balancing prey species or preventing diseases from spreading with the help of scavengers. This method of restoration is favored by policymakers and those with environmental management positions because there is a clear path to the desired results, however, rewilding itself is not so black and white. The debate over whether or not rewilding should have one distinguished definition is an issue that is persistently spoken amongst many conservationists and politicians; however, this turmoil is taking away from the reason rewilding was established in the first place. The two main objectives of this article are to inform the public on what rewilding is and why it can be effective, and what can be done to prompt policymakers to understand why rewilding should retain its experimental nature.

There are risks and uncertainties that come with rewilding projects because although its project members intend for a specific result to occur, nature is unpredictable and cannot be controlled. That is exactly why rewilding should remain a flexible term that caters to each geographic region specific to what the ecosystem needs to become self-sufficient.

The book Rewilding: The Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery by Paul Jepson and Cain Blythe is an extremely digestible and informative piece of literature that encompasses various factors of rewilding, from its origin to its application, and all of the concerns that come with adopting it. The first step in making any progressive policy drafted and implemented, is educating the public about the fundamental goals of such an ambiguous perspective of rewilding the world. Once the public and those native to the lands that are prospects for rewilding are informed of what rewilding entails, they can become part of the movement that creates positive changes to the landscape. Failure to connect the public with rewilding initiative is unfortunately already happened in some part of the world such as Latvia where local farmers and landowners opposed rewilding because it threatened agrarian culture landscapes. Western European NGO’s wanted to introduce wild horses onto abandoned farmland however national political movements resisted the movement, however these wild horses have successfully cleared invasive plants and made way for native plans and animal to return to the natural meadows. “Postcolonial environmental historians argued that the division between nature and society on which a wilderness model is based are largely absent in some parts of the world.”³The differences in costs and benefits from rewilding differ by social groups and the tension that rises can be accredited to methods of environmental governance which are encoded in legislation, subsidy regimes, and territories.³ Once we are able to address these issues we can then shift the focus on restoring natural landscapes that have been degraded due to human influence.

As mentioned previously in the article there is an issue with implementing rewilding as a conservation effort that the public has the power to solve and kickstart projects here in North America as in Europe. The social effects of conservation policies and practices are not well understood, especially in the United States; and unlike our European neighbors there is not as close of a connection between the public and nature. Efforts to inform U.S. residents of conservation and management policies is shown through a carefully cultivated list that presents the top 40- high priority research questions that are directed to inform current and future decisionmakers about ecological processes in the U.S. These questions were created through an open and inclusive process that included interviews with policy makers and scientists. In this article they stated that substantive communication among producers and user of knowledge is essential for developing credible, relevant, and legitimate solutions to conflicting demands for conservation and resource management. ⁴ One of the questions asked in this article is “What are the ecological, social, and economic costs and benefits of different mechanisms of conservation funding?” I believe it is important to single out this particular question because although public support is a major factor to implement rewilding, funding of the projects is also a concern worldwide. Their solution to this question is to look out for diverse mechanisms such as tax incentives and government oil and gas royalties which can be effective for conservation on public or private lands, depending on the regions specific private entities. These solutions are bound to look different from country to country but the first step into the future is making these compromises nationally understood so as to clear any long-standing issues with landowners and the public in general.

To say we are starting from scratch would be inaccurate due to the success that occurred in Yellowstone National Park with the reintroduction of grey wolves along with the proposed Western Rewilding Network which are large reserves spanning across the American West designed to protect and restore biodiversity and habitats for threatened and endangered species. ⁵Early management did not protect wildlife which lead to the deliberate elimination of wolves and cougars⁶, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to reintroduce wolves which led to a balance in the elk population and the prospected increased biodiversity of the area. It is because of the history with the neglect of wildlife in places like Yellowstone that national awareness of environmental issues arose and the creation and adoption of the Endangered Species Act passed in 1973⁷.

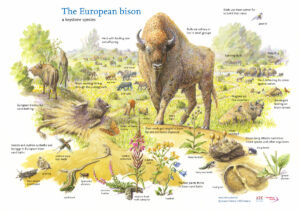

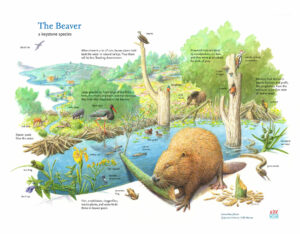

It is important to understand that to implement future projects such as this one there will be oppositions with landowners and specifically farmers who will protest the reintroduction of carnivores such as the grey wolf, but rewilding is not limited to the reintroduction of predators and should not be the poster child for rewilding. Although the Western Rewilding Network and the Yellowstone project primarily focusing on Grey Wolves and Beavers, there are a plethora of endangered species and keystone species, an organism that helps hold the system together, ⁸ that can be reintroduced through rewilding using the methods needed to properly integrate the animals into the ecosystem.

Since 2000 there has been an increase in the number of scientific articles with rewilding in the title or keywords on the Web of Science database and the Google Scholar database.³ Through my search for a better understanding on policies in rewilding not only in North America but worldwide, I was met with a lot of unanswered questions as I’m sure this article results in as well. To answer these unsolved questions, an approach that can be taken to inform future rewilding initiatives may include five key research areas: understanding the links between actions and impacts, improving risk assessment processes, predicting economic costs and benefits, identifying social impacts and developing a framework for monitoring and evaluation.⁹ The article that mentioned these key research areas attempts to make rewilding fit for policy and although that goes against what most conservationists seek for their projects, in order for rewilding to make it’s mark in the States there has to be a consensus on the parameters of what rewilding entails. Unfortunately, the U.S. lacks a strong voice for the environment which can be because of the unsteadiness that comes with presidential elections, not to mention how polarized the nation has become with issue that frankly shouldn’t be political in the first place. The book mentioned earlier in the article asks the question why rewilding so readily becomes political when it is put into practices and concepts from cultural and social theory attempt to answer them. The way they construct the methodology of the issues with applying rewilding is by splitting it up into narratives, frames, and institutions. Narratives signify the building blocks or components that are combined to create the stories that are told to the world, frames are the manner in which people interpret concepts and how they relate them to existing frames to attempt to understand them, and finally the institutions for conservation operating today use linear thinking based on causality.¹⁰ It is because of the conceptual resources that redirect the public opinions on rewilding instead of what it actually is; an ongoing, flexible process that aims to allow nature to be self-sustaining while reducing human impact through restoration of species and ecological processes.³

North and South America have the potential to step into a greener wilder future through promoting biodiversity unique to the varying landscapes of their regions. Rewilding Europe has proclaimed their vision is to put forward a new conservation efforts with wild nature and natural procedures as key elements where rewilding is applicable to any type of landscape or level of protection.¹¹ Because there is such a strong European heritage with wild nature, they are able to wield their appreciation for the environment and innovate new way to protect it and let it flourish. They consistently release a strategic plant for rewilding in which they introduce their objectives and goals and how they attempt to delivery said strategies.

They showcase a total of 10 different projects ranging from Spain to Ukraine all with unique reintroductions that have allowed the landscapes to become wilder and more self-sustaining. They are approaching rewilding with a proactive initiative, using the resources they have to prevent their gorgeous landscapes from losing their natural image, and unfortunately if the States only retaliate in a reactive approach much biodiversity will be lost. Giving nature back the power to maintain its inhabitants in a way protects their future and quality of life will be no easy feat, but there are projects put into place that have laid the foundation for optimistic results. Considering the global biodiversity crisis that is occurring, it is key to focus of restoring and conserving biodiversity at local and global scales.¹²We will never be able to return nature to its original pristine composition, however it is our duty as inhabitants of this planet to do everything in our power to work together with nature in preserving the environment that we have. It all starts with a conversation and as long as everyday people are fighting for a cleaner environment, we have the power to elect sound-minding politicians that align with the views of progressive organizations such as Rewilding Europe, and give our world a fighting chance. Europe has set the bar with rewilding initiatives, but the United States and many other countries all have untapped potential in creating a social and moral movement that aims to protect the one and only planet we have; but it all starts now and it starts with you.

1.“What Is Rewilding?” n.d. Rewilding Europe. https://rewildingeurope.com/what-is-rewilding/#:~:text=Rewilding%20means%20working%20at%20scale.

2. “Cores, Corridors, and Carnivores” 2024. Wildlifeconservationtrust.org. 2024. https://www.wildlifeconservationtrust.org/cores-corridors-and-carnivores/#:~:text=The%20Three%20C.

3. Lorimer, Jamie, Chris Sandom, Paul Jepson, Chris Doughty, Maan Barua, and Keith J. Kirby. 2015. “Rewilding: Science, Practice, and Politics.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 40 (1): 39–62. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021406.

4. Fleishman, Erica, David E. Blockstein, John A. Hall, Michael B. Mascia, Murray A. Rudd, J. Michael Scott, William J. Sutherland, et al. 2011. “Top 40 Priorities for Science to Inform US Conservation and Management Policy.” BioScience 61 (4): 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2011.61.4.9.

5. Ripple, William J, Christopher Wolf, Michael K Phillips, Robert L Beschta, John A Vucetich, J Boone Kauffman, Beverly E Law, et al. 2022. “Rewilding the American West.” BioScience, August. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biac069.

6. Boyce, Mark S. 2018. “Wolves for Yellowstone: Dynamics in Time and Space.” Journal of Mammalogy 99 (5): 1021–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyy115.

7. National Park Service. 2016. “Wolf Restoration – Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service).” Nps.gov. National Park Service. 2016. https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/wolf-restoration.htm.

8. National Geographic Society. 2023. “Keystone Species.” Education.nationalgeographic.org. May 9, 2023. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/keystone-species/.

9. Pettorelli, Nathalie, Jos Barlow, Philip A. Stephens, Sarah M. Durant, Ben Connor, Henrike Schulte to Bühne, Christopher J. Sandom, Jonathan Wentworth, and Johan T. du Toit. 2018. “Making Rewilding Fit for Policy.” Edited by Martin Nuñez. Journal of Applied Ecology 55 (3): 1114–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13082.

10. Jepson, Paul, and Cain Blythe. 2022. Rewilding : The Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Mit Press.

11. “Three-Year Strategic Plan 2019-2021.” n.d. https://rewildingeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Rewilding-Europe-Strategic-Plan-2019-2021_website.pdf.

12. Genes, Luísa, Jens-Christian Svenning, Alexandra S. Pires, and Fernando A. S. Fernandez. 2019. “Why We Should Let Rewilding Be Wild and Biodiverse.” Biodiversity and Conservation 28 (5): 1285–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01707-w.

Tags from the story

Environmental Science

Nomination-Journalistic-Explanatory

rewilding

Rewilding Europe

The Environmental Protection Agency

United States

Andrea Realyvasquez

Hello! My name is Andrea Realyvasquez and I am in my sophomore year here at St. Mary’s University, studying to receive a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Science. If you are more interested in my other works feel free to click on my profile!

Author Portfolio Page