It was 1950 when Rosalind Franklin stepped foot into Kings College. She had just left Cambridge University and was hopeful for new beginnings. She was determined to figure out what makes up all genetic information, DNA. Kings College wanted Franklin on their team to use her expertise in X-ray diffraction, and they offered her a three-year fellowship. At thirty years old, she was already a well-known scientist and wanted to use her knowledge to figure out the biological structure of DNA. After World War II, there was an explosion of science and technology. There was a race for who would provide the most research on the structure of DNA.1 Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) had just been discovered as the genetic code of all organisms, and Rosalind Franklin was inspired to be a part of this discovery.

Her love for the sciences began at an early age. Rosalind Franklin grew up in a comfortable environment. Both sides of her family were involved in social and political works. Ironically, her father was also on the road to becoming a scientist, but due to the war, he was limited to being a college professor. She was born in London and went to an all-girls school to prepare for her career. She attended Newnham College, a woman’s college at Cambridge University. There she received her Doctorate and left with her Thesis of “The Physical Chemistry of Solid Organic Colloids.” During this wartime, it was important to either choose marriage or to further one’s education. You could not hold an academic post and marry. Franklin dedicated herself to her research, and chose not to marry; she wanted to be treated as a scientist.2 Her father was hesitant in her decision, knowing that it was difficult for a woman to have this kind of career.

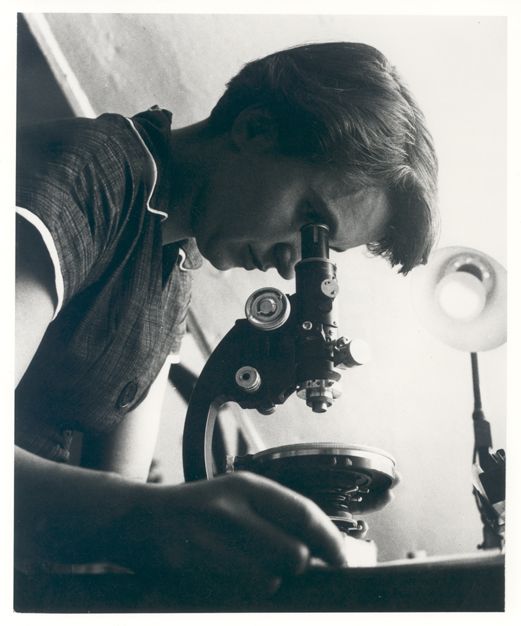

In the Cavendish Laboratory, Rosalind typically spent eight and a half hours each day. In her lab, she worked independently and diligently. Her research outcome was very impressive. She helped tremendously with the emergence of the coal industry and its contributions to the war. Franklin was a part of the British Coal Utilization Research Association (CURA), where she worked with crystallography and molecular biology.3 During this time, many other graduate students would be barely publishing anything, but Franklin had already published five scientific papers where she was the sole author of three of them. Her coal research is still being used to this day. After her research in the coal industry, she moved to Paris where she continued her scientific studies. Unlike her studies with the CURA, her laboratory in Paris consisted of a closed society of equals. Here she worked with Jacques Merging to study the techniques of X-ray diffraction. In X-ray diffracting, the X-ray beams are passed through a crystal and are recorded on film, where then the pattern was analyzed. During this time, Professor J.T. Randall offered her the Turner Newall Research Fellowship at Kings College in London. Here, she would assist in building an X-ray diffraction unit in the laboratory. However, she was not welcomed at Kings College. Similar to Cambridge and Oxford where she had previously studied, Kings College was male-dominated and did not take female scientists seriously. There were very few female scientists at Kings College. According to Maddox, there was only one other woman alongside of Franklin, and eight women in the senior department. Here she struggled with sexism, and felt out of place being both Jewish and a woman. For example, while the men had a private dining room, the female staff were relegated to the student’s cafeteria. This made Franklin angry, and she refused to share her X-ray crystallography until she was treated as an equal.4 Furthermore, being that she was a wealthy Anglo-Jew, she felt out of place in a school were the priesthood was a primary focus.

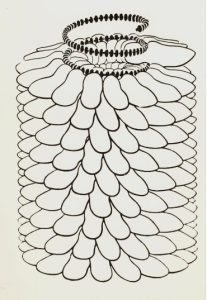

One of her colleagues, Maurice Wilkins, also did research at Kings College. There he worked on similar research to that of Rosalind, causing conflict between the two. Rosalind was unaware that another scientist was working on DNA. It did not help that the day Rosalind was brought to Kings College, Wilkins was absent.5 Rosalind was simply under the impression that she and Gosling were the only researchers at Kings College, while Wilkins was under the impression that Rosalind had been brought in to be his assistant in his research. This caused Wilkins to have a hatred for Rosalind. Wilkins had been known for his condescension of female scientists, being that throughout his career he had never supervised a female student. This created the conditions for the two scientists to have tension with each other, and it left Rosalind isolated with no companionship with her fellow colleagues. During the first eight months, she worked alongside of Gosling to create a micro camera, in hopes of using it to capture an image of DNA. In the fall of 1951, Rosalind had discovered the helical shape of DNA. After years of research, she was able to discover the B form of DNA, and she located the sugar-phosphate backbone of the molecule. “The highly crystalline fiber diagram given by DNA fibers is obtained only in a certain humidity range, about 70% to 80%,” she noted. “The general characteristics of the diagram suggest that the DNA chains are in a helical form.”6 Rosalind and Gosling were able to do this by using a DNA fiber and an X-ray beam for 100 hours of exposure. What they found was revolutionary. The rays produced a pattern on a photographic plate and exposed the structure of DNA and its helical form. After the fifty-first diffracted image, they were able to capture a clear photo of the DNA. This photo is known as “Photo 51” and it changed the future of science.7

Her research with high humidity is what made her research so unique. “When hydrated to absorb water, the fiber became longer and thinner. When placed over a drying agent, it changed back. This transformation explained why earlier attempts—made by Wilkins, among others—to understand DNA’s structure had been unsuccessful, as they had been looking at a blur of the two forms.”8 Francis Crick and James Watson were conducting similar research at Cambridge University. Wilkins would communicate his frustrations with Watson and Crick, explaining how “Rosie” would cause trouble. Rosalind Franklin later led a seminar discussing her work at Kings College. Watson and Crick then decided to use her seminar to conduct their model of the structure of DNA; however, their model was incorrect. Tired of not being taken seriously as a female scientist, Franklin left her studies at KCL to transfer to a secular institution within the University of London. “I may be moving from a palace to the slums,” she wrote to a friend on March 10, 1953, “but I’m sure I will be happier.”9 Back at King College, Ray Gosling gave the photographs he and Franklin had taken to Wilkins. “Rosy, of course, did not directly give us her data. For that matter, no one at King’s realized they were in our hands.”10

On January 30, 1953, Wilkins went to Franklin’s room to present to her his solved structure of DNA using her images. Franklin was unaware that they had used her images from her research, and surprisingly, it did not bother her. However, Franklin noticed how he was wrong in his findings and had made a chemical mistake in the phosphates of the backbone. He also suggested that the DNA was triple-stranded, which we know today is wrong. Watson and Crick returned to their studies and discovered that the two strands of nucleic acid were antiparallel.11 Finally, Watson and Crick began their publication. In their publication, they were ashamed that all of their experimental studies had been done at Kings College, and could be greatly attributed to Rosalind Franklin and her X-ray diffraction.

At Birkbeck College, Franklin was able to continue her research on the tobacco mosaic virus. During her research of the virus, Watson, Crick, and Franklin became close friends. From 1954 to 1958, they exchanged research, ideas, and conversations on the tobacco mosaic virus. She even toured Spain with Crick and his wife Odile in spring of 1956.9 After her vigorous research, she was able to complete a seventeen-paper publication. This led her to become increasingly important in the science community and led her to attend various conferences in the United States. Sadly, she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 1956. Even through her treatment regimen, three operations, and chemotherapy, Rosalind still continued her research for the next two years. This ultimately led to her death in 1958 at the age of thirty-seven. The discovery of the shape of the DNA helix got Crick, Watson, and Wilkins awarded a Noble Prize in 1962. They gave little credit to Franklin, saying that they were “stimulated by a general knowledge” of Franklin’s unpublished research.13 Back at Kings College where Franklin spent two miserable years of her career, they dedicated a building to her and Wilkins for their research. Her discovery of the structure of DNA unlocked the door to understanding the function of DNA. Without her discovery, we would have not been able to learn how DNA is copied and used by the cell to create proteins. Her work on coal, viruses, and DNA will forever be used in the world of science and her courage will never be forgotten. Rosalind Franklin was unable to get the recognition she deserved as a feminist icon for woman in science.

- Sarah Rapoport, “Rosalind Franklin: Unsung Hero of the DNA Revolution,” The History Teacher 36, no. 1 (2002): 317. ↵

- Hugh A. Stewart, “Franklin, Rosalind (1920–1958),” in Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia, ed. Anne Commire, vol. 5 (Detroit, MI: Yorkin Publications, 2002), 746. ↵

- Barbara Wexler, “Franklin, Rosalind,” in Genetics, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2018), 57. ↵

- Sarah Rapoport, “Rosalind Franklin: Unsung Hero of the DNA Revolution,” The History Teacher 36, no. 1 (2002): 323. ↵

- Sarah Rapoport, “Rosalind Franklin: Unsung Hero of the DNA Revolution,” The History Teacher 36, no. 1 (2002):319. ↵

- Hugh A. Stewart, “Franklin, Rosalind (1920–1958),” in Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia, ed. Anne Commire, vol. 5 (Detroit, MI: Yorkin Publications, 2002), 747. ↵

- Barbara Wexler, “Franklin, Rosalind,” in Genetics, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2018), 56. ↵

- Brenda Maddox, “The Double Helix and the ‘Wronged Heroine,’” Nature 421, no. 6921 (January 23, 2003): 67. ↵

- Brenda Maddox, “Franklin, Rosalind Elsie,” in Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, vol. 21 (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2008), 68. ↵

- Jenifer Glynn, “Rosalind Franklin: 50 Years On,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 62, no. 2 (2008): 254. ↵

- George B. Kauffman, “Franklin, Rosalind,” in Chemistry: Foundations and Applications, ed. J. J. Lagowski, vol. 2 (New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004), 125. ↵

- Brenda Maddox, “Franklin, Rosalind Elsie,” in Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, vol. 21 (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2008), 68. ↵

- Theresa Esquerra, “Exploration of Common Law Fraud in Scientific Discovery: The Case of James Watson, Francis Crick, and Rosalind Franklin,” Landslide 4, no. 4 (March 1, 2012): 37. ↵

16 comments

Olivia Lauer

Very interesting article! Before reading this I havent known very much about Rosalind Franklin. Its interesting knowing how into learning all about genetic information and how it comes to be what it is. She put a lot of work into becoming who she became. She was in the same place for 8 and a half hours. Congratulations are getting your work published!

Karly West

Such an interesting and informative article! I had never heard of Rosalind Franklin before this article but now I’m surprised she’s not more well-known for her talents. It’s so aggravating to learn that her research on DNA was unfairly not attributed or credited to her due to sexism and her work was given to male scientists who had no idea what they were doing! She should be recognized as a role model for women in STEM because sadly there is still sexism in this field.

Carolina Wieman

Rosalind is an incredible example of a woman being pushed aside for her STEM achievements while men swoop under and take their achievements. This woman not only spent hours upon hours within the lab testing her data but also realized that when the boys presented their data they presented it wrong! Once those realized and the men felt ashamed for their actions the credit was rightful out upon Rosalind Franklin.

Helena Griffith

I was inspired to ponder about historical women by this article. It is incredible that these folks claimed ownership of Franklin’s findings. I wonder how frequently this has occurred throughout history. Franklin’s account’s wording is excellent and brings her experiences to life. Congratulations on the honor; this article deserved it because it was so good.

Franchesca Tinacba

As someone who is going through a biology degree as a woman, it is so inspiring to see many other women conquer the social stigma of men and science. I believe this article did a fantastic job portraying Franklin’s life and her greatest accomplishment. Women like her make me feel as if I too can become something great in the scientific world.

Courtney Mcclellan

This article made me think about women who have been forgotten by history.It is astonishing that these men took Franklins research and declared it their own. It makes me wonder how many times this has happened throughout history.Franklin’s story is very impressive and the writing really brings her experiences to life. Congratulations of the award this article was amazing and it is well deserved.

Dylan Vargas

Reading this article made me think more on how the discovery of the structure of DNA and how it was a struggle for Rosalind Franklin to even get knowledge. The article goes into detail of her journey on sexism and her science and discovery. I enjoyed the way the story was told, the start of her education to the lead onto Kings College where see wasn’t taken seriously and the eventual find of the structure of DNA based on her X-ray diffraction. It makes me think how women, even one of science, where treated and how they were pushed into the shadow even when it comes to a massive discovery like DNA structure.

Sophia Phelan

This is such an important story especially given the underrepresentation of women in science. I enjoyed this article and the way you told it.

Hoa Vo

I have heard of Rosalind Franklin during my genetic class but did not really know much about her until I read this article, and I wished that I knew this amazing woman earlier. She is a real talented scientist with a huge contribution to the research of DNA complex structure. However, it is sad that her hard work is not recognized and get credit because of the gender discrimination system at that time where woman did not have the same position as men had. Fortunately she got credit at the end and it’s my honor to receive these knowledge from her finding.

Grace Malacara

It’s upsetting to read about women who were marginalized just because they were female. So many accomplishments have gone unnoticed, so many great and significant women have gone unnoticed in history. However, this was a pretty interesting piece to read; I loved learning about Rosalind Franklin because I had never heard of her before. Her experience is inspirational, and I admire her for being tough and refusing to accept disrespect from coworkers simply because she was a woman. Finally, congrats on your nomination!