De-extinction is the process of bringing an extinct species back to life by using genetic sequencing and cloning technologies to bring the extinct creature back to life using distant relatives. The idea of reviving animals that have been extinct for thousands of years is getting closer to reality because of significant advancements in areas like genetic engineering and cloning 12. But because we can now do so, these developments have sparked discussions over whether it is morally acceptable to revive a species and play god in the process.

On the one hand, humans have a moral right and responsibility to revive species whose extinction was largely caused by human activity, whether it was through overhunting or a change in the environment caused solely by industrialization. This argument states that the loss of biodiversity and ecological functions because of an extinction event can be partially restored through the de-extinction of a key species. By bringing back species like the woolly mammoth, the dodo bird, the passenger pigeon, and other species like them, some believe that we could repair ecosystems and help mitigate some of the environmental damage inflicted by human actions and right our wrongs to said species in a sense.

On the other hand, one could also argue that de-extinction raises many ethical questions and risks causing the revived species more harm than good. Reviving an extinct species could result in a genetically unstable creature that is more likely to die quickly or in agony, according to this argument. If this isn’t the case, it might disrupt modern ecosystems and disturb the natural balance that has grown since the disappearance of the species. Additionally, funding for contemporary conservation efforts for endangered species would be a more effective use of the funds required to save a species from extinction.

This essay will look at two sides of the argument to whether or not is is a good idea or a bad idea to bring back a species just because we can. Should we concentrate our efforts on protecting the extinct and soon-to-be-extinct species, or is it reasonable to try to bring those long gone back to life?

Case for De-Extinction

One of the primary arguments in favor of de-extinction is that bringing extinct species back to life can restore ecosystems that have been upset by the extinction of certain important or keystone species. The loss of a keystone species can be devastating and cause many problems within an ecosystem if not cause its collapse. An example of such would be if coral were to go extinct. In the absence of coral, many species that use it as a home or for shelter would instantly lose one of the most important parts of their ecosystem. The restoration of a keystone species could undo the harm caused by their absence within a set amount of time.

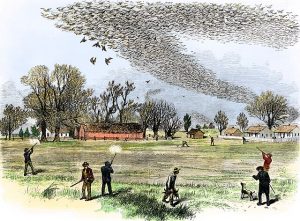

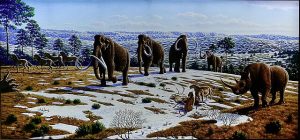

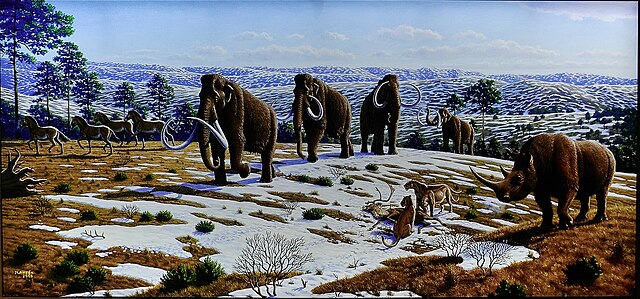

Woolly mammoths, for instance, were formerly essential to the Arctic tundra’s ecosystems thousands of years ago. By clearing forests and establishing open areas, these enormous creatures contributed to the upkeep of the grasslands, providing habitat for a diverse range of plants and animals to strive in. Since humans are most likely to be the reason for the demise of mammoths, the tundra has changed, allowing woods and shrubs to develop where the grasslands used to be located. Restoring mammoths could bring back the former ecosystem that they had once inhabited and potentially stave off the effects of climate change. By grazing and traveling in herds, mammoths might help trap carbon in the soil by allowing for other types of fauna to flourish, reducing greenhouse gas emissions 3. Similarly, the revival of other extinct species could help fix broken food webs and restore ecosystems to their former glory. For example, the dodo bird, which went extinct in the 17th century, was crucial to the pollination and spreading of certain plant seeds on the island of Mauritius. Since their disappearance, certain plant species have been left struggling to thrive, as they lack the specialized seed dispersion systems originally provided by the bird 4. Reintroducing the dodo could help these plant populations flourish as they once had. Some argue that humanity has a moral duty to make amends for species that became extinct as a result of human intervention, such as overhunting or habitat degradation. Because of overhunting, species like the passenger pigeon, which once numbered in the billions, went extinct in the early 20th century. Some people think that reviving such species will undo the harm that humans have done to the ecosystem and restore some of the biodiversity that used to be present.

Another argument for de-extinction states that it could lead to advancements in science and technology. The process of bringing back extinct species involves techniques such as cloning and CRISPR. These technologies have proven to have applications beyond just de-extinction. Currently, the way that de-extinction works involves using CRISPR technology to make precise edits to an organism’s genome, potentially enabling them to “recreate” extinct species by introducing their genes into the genome of a closely related living species. Advancements in developing techniques like this could improve the fields of genetics, medicine, and conservation biology. Insights gained from studying the genomes of extinct species could shed light on the evolutionary adaptations that allowed them to thrive in their environments, providing us with valuable information on how species evolve in response to environmental changes. These tools could be applied to endangered species in the present by editing the genome of these endangered animals to make them more resilient to disease or environmental stress 56. In a theoretical case, de-extinction technology could rescue species that are on the verge of extinction by improving their chances of survival.

The main ethical argument in favor of de-extinction is that humans have a moral obligation to restore the species that we have personally wiped off the face of the planet. This argument is based on the idea that if humans caused the extinction of a species, either directly through hunting or indirectly through habitat destruction, we have a moral responsibility to bring it back if at all possible. This argument states that to right our wrongs we must do justice to those extinct species and give them a chance at living once more. The extinction of species like the woolly mammoth, the dodo bird, and the passenger pigeon is attributed to humans hunting them to extinction. By reviving these species, we would be taking responsibility for our past actions and restoring the former ecosystem that has changed due to their absence. In this context, de-extinction can be seen as an obligation that helps the environment by restoring a keystone species, rights our past wrongs, and additionally enhances our understanding of science and technology 78. In this sense it is not entirely about “playing god” but about taking responsibility for our ecological footprint as a species from the past and present, as well as attempting to correct the imbalances we have created in nature. This however is not a sentiment that everyone can agree with due to some disagreements in how de-extinction may be carried out or how it could negatively affect the ecosystem.

The Case Against De-Extinction

While the argument for de-extinction indicates that it could restore ecosystems and biodiversity, some are opposed to the concept since the reintroduction of extinct species may have unpredictable and potentially dangerous ecological outcomes that we can never completely account for. Ecosystems are complex, and the interactions between species aren’t easy to determine even when looking back at ecosystems that have previously existed. Introducing a species that has been absent for hundreds or thousands of years could disrupt the balance of the ecosystem that has had hundreds if not thousands of years to adapt and change in the species’ absence. This argument states that the revived species could act as an invasive species in modern-day ecosystems. With the absence of predators or competitors from when they had previously existed, these species may proliferate uncontrollably, outcompeting local species for resources and potentially pushing them to extinction 9. As an example, if the woolly mammoth were reintroduced to the Arctic tundra, it is uncertain how it might engage with present-day species like caribou or musk oxen. The woolly mammoth may outcompete those species for food or alter the environment in ways that harm other species. They could additionally become territorial and begin attacking or pushing other species out of necessary or scarce grazing lands. Additionally, the ecosystems that existed when these species were alive have dramatically changed in their absence. Climate exchange, habitat destruction, and the introduction or evolution of modern species have reshaped ecosystems in ways that might make it hard if not impossible for them to survive in these new environments. Even if a species like a passenger pigeon were effectively brought back, it is almost impossible to predict whether or not the forests could sustain the massive flocks that had existed before. The habitats that those species once thrived in may not exist in a form that could maintain them to the point that bringing them back to life is pointless if we are just going to watch them disappear from the planet again.

Another issue that surrounds de-extinction is the overall health of the animals that are revived. The method of cloning and genome editing is still relatively new, and the animals that can be produced via these techniques are regularly afflicted by chronic if not immediate health defects or issues. Cloned animals generally tend to have shorter lifespans and are more vulnerable to genetic defects than animals born via natural reproduction 10. Some argue that bringing an animal back from extinction is unethical if it’s going to be afflicted by chronic health conditions all of its life just to die again in more agony than the last time it roamed the earth. Even if the genetic techniques utilized in de-extinction were perfected, the revived species would probably face hard situations in adapting to modern environments. In many instances, these animals would likely end up being kept in captivity for the rest of their lives, as their natural habitats do not exist, are too dangerous for them to continue to live in, or are too much of a danger to the biodiversity of that environment. This brings up the point of whether or not it is right to bring back an extinct species if the only place it can thrive is a zoo or wildlife reserve for the rest of its lives. Some argue that this would be tantamount to creating an exotic zoo rather than actual de-extinction and would take away necessary funds that would otherwise be used for protecting species that already exist.

De-extinction offers interesting but controversial possibilities for modern science. While the idea of bringing back species that have long been extinct is fascinating and a test of modern scientific technologies, it raises moral, ecological, and practical questions. People who argue for de-extinction state that we have a moral responsibility to right the wrongs of the past and repair the biodiversity that has been lost because of human actions. In this sense, de-extinction is a way to repair ecosystems, advance cutting-edge technological understanding, and atone for environmental destruction as a result of human interference.

However, the dangers associated with de-extinction are just as conventional. The reintroduction of extinct species could disrupt modern-day ecosystems, cause unpredictable ecological consequences, and divert assets away from urgent conservation efforts. On top of this, the ethical concerns surrounding animal welfare the artificial situations in which revived species are probably forced to live, or the whole failure to reimplement them into their surroundings can not be ignored.

The question isn’t simply whether we can bring extinct species back to life but whether or not we should. While de-extinction gives interesting scientific possibilities, the moral and ecological implications ought to be carefully considered before taking any steps toward reviving species that have long disappeared from the Earth. In the long run, our main interests ought to be on preserving the species and ecosystems that still exist on this planet and making sure that we don’t let them become extinct as well.

- Martinelli, Lucia, Markku Oksanen, and Helena Siipi. 2014. “De-Extinction: A Novel and Remarkable Case of Bio-Objectification.” Croatian Medical Journal 55 (4): 423–27. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2014.55.423. ↵

- Shapiro, Beth. 2015. “Mammoth 2.0: Will Genome Engineering Resurrect Extinct Species?” Genome Biology 16 (1): 228. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0800-4. ↵

- Poquérusse, Jessie, Casey Lance Brown, Camille Gaillard, Chris Doughty, Love Dalén, Austin J. Gallagher, Matthew Wooller, et al. 2024. “Assessing Contemporary Arctic Habitat Availability for a Woolly Mammoth Proxy,” Scientific Reports 14 (1): 9804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60442-7. ↵

- “Extinctions on the Island of the Dodo Are Pushing Plants towards Extinction.” n.d. Accessed October 13, 2024. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/march/extinctions-island-dodo-pushing-plants-towards-extinction.html. ↵

- Sherkow, Jacob S., and Henry T. Greely. 2013. “What If Extinction Is Not Forever?” Science 340 (6128): 32–33. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1236965. ↵

- Sandler, Ronald. 2014. “The Ethics of Reviving Long Extinct Species.” Conservation Biology 28 (2): 354–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12198. ↵

- Lean, Christopher Hunter. 2020. “Why Wake the Dead? Identity and De-Extinction.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 33 (3): 571–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-020-09839-8. ↵

- Odenbaugh, Jay. 2023. “Philosophy and Ethics of De-Extinction.” Cambridge Prisms: Extinction 1 (January):e7. https://doi.org/10.1017/ext.2023.4. ↵

- Genovesi, Piero, and Daniel Simberloff. 2020. “‘De-Extinction’ in Conservation: Assessing Risks of Releasing ‘Resurrected’ Species.” Journal for Nature Conservation 56 (August):125838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2020.125838. ↵

- Graeff, Nienke de, Karin R. Jongsma, Josephine Johnston, Sarah Hartley, and Annelien L. Bredenoord. 2019. “The Ethics of Genome Editing in Non-Human Animals: A Systematic Review of Reasons Reported in the Academic Literature.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, May. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0106. ↵

- https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ ↵

- “Bringing Extinct Species Back from the Dead Could Hurt—Not Help—Conservation Efforts.” n.d. Accessed October 13, 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/bringing-extinct-species-back-dead-could-hurt-not-help-conservation-efforts. ↵

3 comments

arosales11

Hi Brandon, while I have heard about the whole extension, now cloning situation before in conversations in school , i’ve never actually sat down to read about it. your article helped me learn more about the animals extinction and why it could be benefiting to the world , all in your perspective.

Zoe Klupenger

Hi Brandon! This was an interesting take on your infographic, and I really liked it. This is a subject I am not familiar with, so this was very informative and fun to learn and read about. I like the way everything was organized, and the pictures and visuals you included with it. Nice! Were there any interesting facts you found that you did not include?

Cesia Gonzalez

I enjoyed reading your piece! It’s full of valuable information and the images help the reader understand the reading as they go. I like how at the beginning you showed both sides of the story, and as you move on you begin to make the reader question whether it is ethical and ecological. I’m glad I got to read your piece. Great job!