November 7, 2021

Stop! Collaborate and Listen: Water Quality Cohesion in Bangladesh is Missing

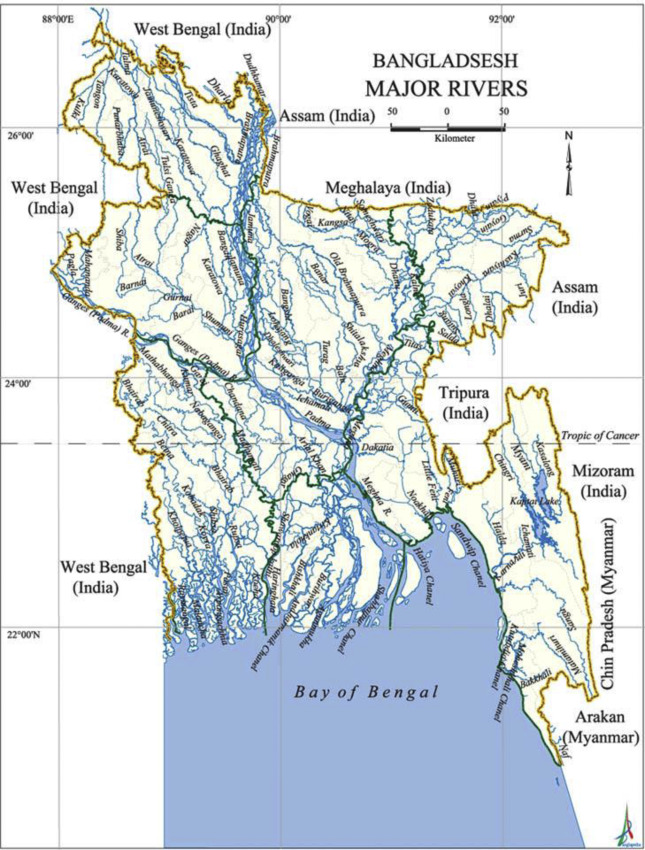

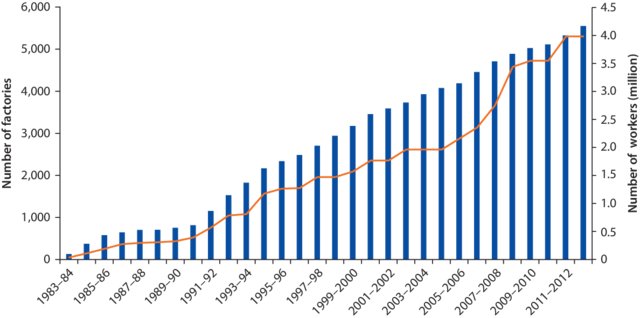

Nestled within a corner adjacent to northeastern India, spanning 57,300 square miles, lies one of the most densely populated countries in Southeast Asia, Bangladesh. The population of Bangladesh is spread out, with roughly 114 million people (76%) living in rural areas, and 36.4 million (24%) living in urban areas, with the largest concentration in the capitol, Dhaka.3 It is classified as a “riverine” country, with a vast amount of rivers and streams that flow from the higher elevations in the northern part of the country down through the rural and urban areas to the south. Four major river systems allow 230 rivers to interconnect throughout the land (Figure 2) which gives 97% of the Bangladesh population access to water. With 20 million residents, the mega-city of Dhaka relies on major rivers such as the Buriganga to sustain their existence. Unfortunately, these water systems are in peril from human-generated factors such as agriculture, industry, mining, power generation, unsanitary waste disposal practices, and other human factors. These factors affect the public health with high amounts of metal contaminants like arsenic, and bacteria such as E. Coli causing increased impacts to human health, and even death.4

In relation to the RMG industries that contribute most of the pollution into the water systems, where does this lack of monitoring come from? Many of the lower tier organizations such as the non-government and civil societies highlight the opaqueness of accountability the government holds the private industrial sectors resulting in pressure put on organizations like the Department of Environment (DoE). The DoE is dedicated to monitoring, evaluating, and enforcement. Although the agency plays a pivotal role in managing the compliance with respect to ETPs, it is often pressured to report that high amount of effluents are being captured by the ETPs, instead of the ETPs not performing optimally and requiring the industry to shut down for repairs. The potential for a conflict of interest between the industrial sectors and government agencies further denotes the lack of cohesion amongst the water management organizations and results in inefficient implementations of strategies including highlighting areas that need to be reevaluated.15

However grim it might seem for the water quality in Bangladesh, many of the management agencies look forward to continuing progress that began in 2009 with the re-election of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina (Figure 5). Standing on a platform devoted to restoring Bangladesh’s water quality while retaining its economic growth, she noted that “Conservation and protection of the environment is a time-honoured ‘responsibility’, not just a necessity.”16 In 2017 she gave a speech at the Dhaka Water Summit that highlighted some of the accomplishments she has overseen during her term in office. The rate of unsanitary human waste disposal in 2003 was 42%, but by 2017 the rate of unsanitary waste disposal was below 1%. She has taken an approach to restore surface water and reduce the amount of groundwater being used, resulting in 7,000 ponds being desalinated by sand filtering, with 4,700 reservoirs constructed to catch and preserve rain water. Plans to build reservoirs in industrial and housing areas are underway, with the installation of rainwater harvesting systems filtration systems for wastes and polluted water.17 Another breakthrough is the backing of the Bangladesh High Court that has ordered 231 out-of-compliance factories to shut down and repair systems to meet DoE clean water requirements18 The fact that the Bangladesh High Court has ordered factories to shut down until operations can meet DoE water quality regulations shows that collaboration is increasing among the agencies that hold power to promote change.

As progress continues and water quality increases, clean drinking water can be provided to the population of Bangladesh. This steady record of improvement showcases the importance of interagency collaboration, and how all individuals will need to adapt in order to maintain access to clean water. Although there is a long journey ahead to clean all the water in Bangladesh, the progress made today shows that collaboration is no longer missing, it is beginning.

- “How Much Water Is on Earth? – Earth How.” n.d. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://earthhow.com/how-much-water-is-on-earth/. ↵

- “Water Facts – Worldwide Water Supply | ARWEC| CCAO | Area Offices | California-Great Basin | Bureau of Reclamation.” n.d. Accessed October 29, 2021. https://www.usbr.gov/mp/arwec/water-facts-ww-water-sup.html. ↵

- Hossain, Md Amir. 2017. “Bureaucratic System in Bangladesh.” Review of Public Administration and Management 05 (02). https://doi.org/10.4172/2315-7844.1000214. ↵

- Hasan, Md. Khalid, Abrar Shahriar, and Kudrat Ullah Jim. 2019. “Water Pollution in Bangladesh and Its Impact on Public Health.” Heliyon 5 (8): e02145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02145. ↵

- “River – Banglapedia.” n.d. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/River. ↵

- “Bangladesh Case Study: Economic Development.” n.d. Economic Development, 53. ↵

- “Safety First: Bangladesh Garment Industry Rebounds.” n.d. Accessed October 29, 2021. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/NEWS_EXT_CONTENT/IFC_External_Corporate_Site/News+and+Events/News/Insights/Bangladesh-garment-industry. ↵

- Islam, Md. Saiful. 2021. “Ready-Made Garments Exports Earning and Its Contribution to Economic Growth in Bangladesh.” GeoJournal 86 (3): 1301–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-10131-0. ↵

- Kathuria, Sanjay, and Mariem Mezghenni Malouche. 2016. Toward New Sources of Competitiveness in Bangladesh: Key Insights of the Diagnostic Trade Integration Study. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0647-6. ↵

- Hossain, Laila, and Mohidus Samad Khan. 2020. “Water Footprint Management for Sustainable Growth in the Bangladesh Apparel Sector.” Water 12 (10): 2760. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12102760. ↵

- Restiani, Phillia. n.d. “WATER GOVERNANCE MAPPING REPORT: TEXTILE INDUSTRY WATER USE IN BANGLADESH,” 49. ↵

- Islam, Md., M. Uddin, Shafi Tareq, Mashura Shammi, Abdul Kamal, Tomohiro Sugano, Masaaki Kurasaki, Takeshi Saito, Shunitz Tanaka, and Hideki Kuramitz. 2015. “Alteration of Water Pollution Level with the Seasonal Changes in Mean Daily Discharge in Three Main Rivers around Dhaka City, Bangladesh.” Environments 2 (4): 280–94. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments2030280. ↵

- “Water Pollution River Because Industrial Not Stock Photo (Edit Now) 753258850.” n.d. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/water-pollution-river-because-industrial-not-753258850. ↵

- Lindamood, Danielle, Derek Armitage, Dilruba Fatima Sharmin, Roy Brouwer, Susan J. Elliott, Jennifer A. Liu, and Mizan R. Khan. 2021. “Assessing the Capacity for Adaptation and Collaboration in the Context of Freshwater Pollution Management in Dhaka, Bangladesh.” Environmental Science & Policy 120 (June): 102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.015. ↵

- Lindamood, Danielle, Derek Armitage, Dilruba Fatima Sharmin, Roy Brouwer, Susan J. Elliott, Jennifer A. Liu, and Mizan R. Khan. 2021. “Assessing the Capacity for Adaptation and Collaboration in the Context of Freshwater Pollution Management in Dhaka, Bangladesh.” Environmental Science & Policy 120 (June): 104–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.015. ↵

- “HE Sheikh Hasina | Champions of the Earth.” n.d. Accessed October 30, 2021. https://www.unep.org/championsofearth/laureates/2015/he-sheikh-hasina. ↵

- Hasina, Sheihk. 2017. “Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim.” https://pmo.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/pmo.portal.gov.bd/pm_speech/f02109f4_3886_452d_9a57_ab1cdc5dc43b/dhaka_water_conf_290717_eng.pdf. ↵

- “Bangladesh Court Orders 231 Factories Closed to Save River.” n.d. Accessed October 30, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/669408ee151214f18b0fa74533d9674c. ↵

- “Portrait Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Rally Stock Photo (Edit Now) 1707339541.” n.d. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/portrait-prime-minister-sheikh-hasina-rally-1707339541. ↵

Tags from the story

Recent Comments

Rafael Macedo

Firstly one of the things that caught my attention in this article is the quality of the pictures and graphs, they match perfectly with the text. I enjoyed reading this article because I think that we should discuss more bad hygiene conditions. Many of the global health issues we face today, such as infectious illnesses and lack of hygiene, are linked to decreased biodiversity and ecological degradation. We are not above any species, which is why the destruction of the earth is our own death.

18/11/2021

5:09 am

Kimberly Rivera

I loved how detailed this article was. It is sad to see how big corporations/ companies care more about the money of than the effects it has on the environment but I am glad that Bangladesh has taken the opportunity to work together in bettering its water system and reducing the waste that went into this. Hopefully, this long journey will be successful for the long run.

13/11/2021

5:09 am