In South America lies the Amazon Basin, a powerhouse of environmental energy for the rest of the world — “It stabilizes our planet’s climate, contains 20% of the world’s flowing freshwater, and drives global weather systems.”1 Also in the Amazon are indigenous people that hold valuable environmental, cultural, and spiritual connections to the land. Many of the indigenous peoples have shown examples of sustainable actions and living that benefit themselves, the Amazon Rainforest in which they reside, and, inevitably, the rest of the world. Protectors of this valuable and unique region, indigenous people themselves are vulnerable to the threats that occur within it. 2

The Amazon contains an overall population of 47 million inhabitants, with over 2 million of them being indigenous peoples from over 500 distinct groups.3 The Amazon has been inhabited by humans for at least 12,000 years.4 Through this time, many indigenous groups have preserved both cultural practices and ecological knowledge that serve as evidence of sustainable ways of living. For example, according to Vergera et al., “Indigenous peoples have been found to use 200 different species of trees as sources of timber, 100 of which are also used to produce non-timber goods and have domesticated at least 83 plant species.” Their practice of using a large variety of plant species is in sharp contrast to the modern, ever-present agricultural method used today, “…in which only nine plant varieties account for 66 percent of global agricultural production.” The commercial method of using a select few plants in areas has proven demanding, causing soil degradation.5 In the case of indigenous peoples in the Amazon, the variety in plant life helps avoid soil degradation and biodiversity loss. Additionally, some indigenous groups in the Amazon Basin use a variety of strategies for food production, including shifting cultivation, home gardens, agroforestry, hunting and fishing, and more. 6 It is clear from these examples alone that indigenous practices have much to offer in caring for the Amazon.

With the Amazon being rich in plant life (see Fig. 1), the indigenous people help protect more than 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity.7 Plants in the Amazon Basin are not only a source for food for many indigenous people, but are used as medicine as well. One study documented an indigenous community using 467 plant taxa for medicinal purposes. 8 The plants were used for a variety of purposes, including envenomation (treating venomous snake and insect bites), reducing infections, treatments for pregnancy (such as prenatal care, facilitating childbirth and accelerating labor) and treating digestive system disorders. For the application of these medicinal plants, external use was the most common method at 85.9%. Additionally, the plant specialists in this community cared for certain plant species in a small forest garden near the village for emergencies. The study also acknowledged the effectiveness of the medicinal herbs formed from the home gardens, since they have been used frequently by those indigenous communities.9 Similarly, in a rural area in the Ecuadorian Amazon, medicinal plants were observed to “…fulfill health care needs and contribute to local well-being.”10 In the same study, a third of the species cultivated in the home gardens studied were medicinal plants.

These types of traditional uses of plants in the Amazon region suggest that there may be new products for the world in fighting diseases, and indigenous people understand the value of the array of species the Amazon has to offer. The gardens that provide medicinal resources for indigenous people simultaneously reduce pressure on the natural ecosystems of the Amazon region. Home gardens by indigenous people showcase their biocultural knowledge, and the gardens themselves are representations of biodiversity conservation.11

A significant way in which many indigenous tribes are guided in their way of living and caring for the Amazon are often in spiritual beliefs. For example, the Urarina people from the Peruvian Amazon believe in spirits that guard wetland ecosystems and provide protection “…to ensure that its non-human inhabitants prosper”. From this perspective, indigenous people engage in sustainable actions for spirits to indirectly exert that control, and “…awarding greater autonomy and land rights to indigenous peoples may also be beneficial for environmental conservation in the Peruvian Amazon”. 12

Indigenous people have proven to be protectors of the Amazon. In the Brazilian Amazon, there has been shown a significantly large difference in native vegetation loss between indigenous territories and unprotected areas. Rates in native vegetation loss between 2005 and 2012 “…were 17 times lower in Indigenous territories than in unprotected areas of the Amazon.”13 Additionally, recent studies suggest that “…forests in indigenous areas have deforestation rates that are 2-3 times lower than in non-indigenous lands and store significantly more carbon”.14 This stark difference in carbon storage suggests that greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change are better controlled in indigenous areas.

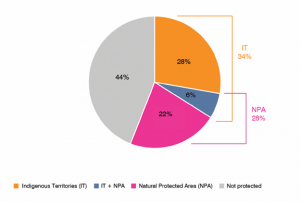

Unfortunately, indigenous areas are increasingly under threat. According to Amazon Watch, “…indigenous peoples occupy 400 million hectares of the Amazon, but there is no legal recognition of their property rights in one-third of this area”. Percentages of indigenous territories and non-protected areas in the Amazon can be seen in Fig. 2. Indigenous areas in the Amazon rainforest often face external threats to their land, such as from mining, illegal logging, and cattle production, forcing indigenous communities to fight for land ownership.15 Indigenous ownership of their territories is critical, since indigenous people have protected the Amazon for millennia, and areas of indigenous territories have shown reduced deforestation rates compared to non-indigenous lands.

The Amazon is a rich environment, but the taking of indigenous lands can have significant risks, such as losing the opportunities to further study medicinal plants to find cures for diseases. Furthermore, continued harm to indigenous areas can accelerate deforestation, reducing carbon storage in the Amazon Rainforest.16 Competition for land has intensified in recent years, especially between indigenous people, governments, and companies. This competition has increased the danger to indigenous groups, where people have been “…harassed, arrested, and murdered for their efforts to protect their land”. Latin America itself is “…consistently ranked as the region with the most killings of land and environmental defenders”. 17 The Amazon, its indigenous inhabitants, and, as a result, the rest of the world, are under threat.

In fighting for their land, indigenous people have been assisted by organizations such as Amazon Watch, that have aimed to give the people a stronger voice against large companies engaged in extractive activities like mining and logging. 18 Along with this help, world leaders have set international policies to improve the Amazon Rainforest, such as “…pledges to halt deforestation and reverse land degradation by 203o, which was signed by over 100 world leaders at the COP26 summit.” 19

Some indigenous communities have worked together to fight for land protection themselves. One such example is Instituto Raoni (Raoni Institute), an organization created by the Kayapó, an indigenous group in the Brazilian Amazon. Instituto Raoni works with the Kayapó and other indigenous groups and use strategies such as trail cameras to document illegal logging in their territory. Additionally, these organization help indigenous communities implement strategies to promote and improve sustainable living and biodiversity. Indigenous communities face many challenges to the protection of their lands, but they have shown through many examples of working together as a community with non-governmental organizations or other world leaders, that they will fight back to protect their lands and the Amazon Basin as a whole.20

The Amazon Basin is filled with communities, many of which help benefit the lands through carbon storage, species protections, and defending against extractive companies. Many indigenous communities have been shown to understand the significance the Amazon provides with intact forests and greater biodiversity, and they operate and live within it (see fig. 3.). The fight for the protection of indigenous lands remains ever-present, since several areas where indigenous people live are not formally recognized as indigenous territory. A significant step towards certifying indigenous communities’ areas is through demarcation, or the process of having clearly drawn, legal boundaries around territories that belong to indigenous people.21 Demarcation legalizes the definition of indigenous areas, and the communities are better able to defend it against land threats such as deforestation and mining.

The Amazon Basin is an invaluable resource for South America and the rest of the world, and indigenous lands have shown to positively impact its environment. Indigenous people have shown they are capable of protecting plant species and forests entirely. Though indigenous people face several threats to their home, they have increasingly received support from organizations and communities around the world in order to ensure they keep their territories. Indigenous people are present in the forest, making their voices heard against threats to their land, and they will always aim to protect it.

- Amazon Watch. Annual Report July 2023 – June 2024. fy2023-annual-report.pdf . ↵

- Amazon Watch. Annual Report July 2023 – June 2024. fy2023-annual-report.pdf . ↵

- Vergara A, Arias M, Gachet B, Naranjo L G, Roman L, Surkin J, Tamayo V, Bueno P, Gagen M, Ferreira M et al. 2022. Living Amazon Report 2022. https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/living-amazon-report-2022/ . ↵

- Vergara A, Arias M, Gachet B, Naranjo L G, Roman L, Surkin J, Tamayo V, Bueno P, Gagen M, Ferreira M et al. 2022. Living Amazon Report 2022. https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/living-amazon-report-2022/ . ↵

- Vergara A, Arias M, Gachet B, Naranjo L G, Roman L, Surkin J, Tamayo V, Bueno P, Gagen M, Ferreira M et al. 2022. Living Amazon Report 2022. https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/living-amazon-report-2022/ . ↵

- Affonso, H., Fraser, J. A., Nepomuceno, Í., Torres, M., & Medeiros, M. (2024). Exploring food sovereignty among Amazonian peoples: Brazil’s national school feeding programme in Oriximiná, Pará state. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 52(1), 178–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2024.2310149 . ↵

- Ndlovu, Mel. Why Indigenous Land Rights Are Key to Protecting the Amazon. 2025 May 30. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/why-indigenous-land-rights-matter/. ↵

- Horáčková J, Chuspe E, Ladislav Kokoška, Sulaiman N, Clavo M, Ludvik Bortl, Zbynek Polesny. 2023. Ethnobotanical inventory of medicinal plants used by Cashinahua (Huni Kuin) herbalists in Purus Province, Peruvian Amazon. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 19(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-023-00586-4. ↵

- Horáčková J, Chuspe E, Ladislav Kokoška, Sulaiman N, Clavo M, Ludvik Bortl, Zbynek Polesny. 2023. Ethnobotanical inventory of medicinal plants used by Cashinahua (Huni Kuin) herbalists in Purus Province, Peruvian Amazon. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 19(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-023-00586-4. ↵

- Caballero-Serrano V, McLaren B, Carrasco JC, Alday JG, Fiallos L, Amigo J, Onaindia M. 2019. Traditional ecological knowledge and medicinal plant diversity in Ecuadorian Amazon home gardens. Global Ecology and Conservation. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00524. . ↵

- Caballero-Serrano V, McLaren B, Carrasco JC, Alday JG, Fiallos L, Amigo J, Onaindia M. 2019. Traditional ecological knowledge and medicinal plant diversity in Ecuadorian Amazon home gardens. Global Ecology and Conservation. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00524. . ↵

- Fabiano E, Schulz C, Martín Brañas M. 2021. Wetland spirits and indigenous knowledge: Implications for the conservation of wetlands in the Peruvian Amazon. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability. 3:100107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2021.100107. . ↵

- Modelli, Lais. 2022. In Brazilian Amazon, Indigenous lands stop deforestation and boost recovery. Mongabay. https://news.mongabay.com/2022/05/in-brazilian-amazon-indigenous-lands-stop-deforestation-and-boost-recovery/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CPrevious%20studies%20have%20shown%20that,to%20Indigenous%20or%20Quilombola%20people. . ↵

- Ndlovu, Mel. Why Indigenous Land Rights Are Key to Protecting the Amazon. 2025 May 30. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/why-indigenous-land-rights-matter/. ↵

- Ndlovu, Mel. Why Indigenous Land Rights Are Key to Protecting the Amazon. 2025 May 30. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/why-indigenous-land-rights-matter/. ↵

- Ndlovu, Mel. Why Indigenous Land Rights Are Key to Protecting the Amazon. 2025 May 30. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/why-indigenous-land-rights-matter/. ↵

- Veit P, Gibbs D, Reytar K. 2023. Indigenous Forests are Some of the Amazon’s Last Carbon Sinks. Carbon Fluxes in the Amazon’s Indigenous Forests | World Resources Institute. ↵

- Amazon Watch. Annual Report July 2023 – June 2024. fy2023-annual-report.pdf . ↵

- Banjo, Fadeke. The Amazon Rainforest: Our Planet’s Lungs at Risk – Why We Must Act Now. 2025 May 14. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/the-amazon-rainforest-our-planets-lungs-at-risk/. ↵

- United Nations Development Programme. 2018. Instituto Raoni, Brazil. Equator Initiative Case Study Series. https://www.equatorinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Instituto-Raoni-Brazil.pdf. ↵

- Ndlovu, Mel. Why Indigenous Land Rights Are Key to Protecting the Amazon. 2025 May 30. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/why-indigenous-land-rights-matter/. ↵