By the end of the Meiji Restoration, one of the three great nobles, Saigo Takamori, had retired. His retirement was a silent and powerful protest against the government and its policies regarding land reform, western ideals, and the now disassembled samurai class. It was a stance he was firm on, and Saigo wished to stay retired in his home province of Satsuma, creating schools for disaffected samurai.1 However, this was not to be. Within a couple of years, a series of actions by both Saigo’s students and the Meiji government pressured Saigo to come out of retirement and declare his intentions to march to the Emperor’s capital. The ensuing war, the Satsuma rebellion, was the war where the last true samurai, and their way of life, went to die.

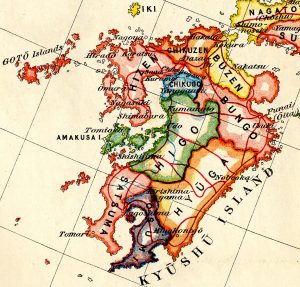

Saigo Takamori retired from his government office in 1873 in silent protest of the Meiji government. From then until 1876, he began to distance himself from political affairs. This was a solid yet silent statement to them in that he did not approve of their policies, like the adoption of western ideals that the government seemed to get accustomed to, and their lack in having a “sense of honor,” with the government’s failure to attack Korea.2 It was, in a way, a repeat of the Sono joi, a sentiment that brought the emperor to power in the first place. It was also one that helped Saigo Takamori and the other two great nobles rise in power. He traveled back to Kagoshima, in the Satsuma province. There he created a number of academies called Shi-gakkō for samurai, whose numbers were boosted by the Meiji Government’s most controversial policy to those of the samurai class. They were affected by the restructuring of the social order, resulting in the dismantling of the samurai class. These reforms heightened after Saigo left office. Samurai privileges, previously only for them, were taken away. One right for samurai that was revoked was their ability to kill commoners who disrespected them. Another reform was the taking away of the samurais’ ability to wield swords, which was implemented on March 28, 1876.3 With these reforms came rebellions all across the changing nation.

In 1874, a rogue samurai leader led 12,000 other samurai to reinstate their daimyo.4 Another two rebellions rose up in 1876, both based in Kyushu. These rebellions were each put down, and their leaders were executed.5 Saigo observed the rebellions with conflicting emotions. However, the opinions of the samurai in Saigo’s academies were much more profound, especially among radicals in the Shi-gakkō schools, who freely spoke of wanting to spark a rebellion. This open talk of rebellion worried the Meiji government, and in late 1876, they sent spies to discourage members of the Shi-gakkō from speaking of or attempting rebellion. When this failed, the Meiji government sent a warship in January of 1877, planning to remove munitions from the province. During this time, Saigo was hunting in Konejime, a location on the east of Satsuma. The plan reached the students before the ship got to the province, and this action of the Meiji government infuriated them. A small group of these students raided the powder house in Somuta, in the city of Kagoshima on January 30, in response to the incoming vessel. They captured about 60,000 rounds of ammunition before the ship was able to disarm the province. Worse still for the Meiji government, the leader of the spies they sent to Kagoshima was captured near the same time as the raid, and he was tortured to confess to the planning to assassinate Saigo and allow the Meiji government to wipe out pupils of the Shi-gakkō. These confessions were almost certainly fake, due to the fact that the spy leader was tortured, and that no suspicious troop movements had been made by the Meiji government. However, it was all that the Satsuma samurai needed to begin the preparation for war.6 On February 3, Saigo returned from his hunting trip, and after a few days, he declared his decision to march to the Meiji government in Tokyo. Saigo Takamori and his Satsuma rebels, made up of samurai, would face off against the new imperial army, made up of Conscript peasant soldiers.

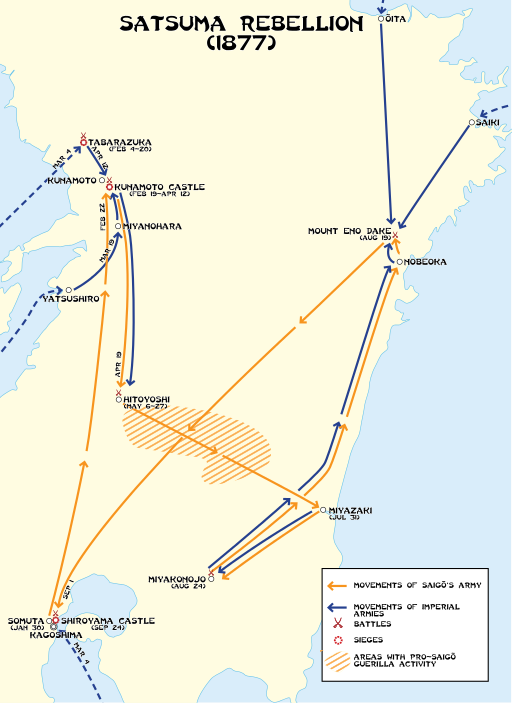

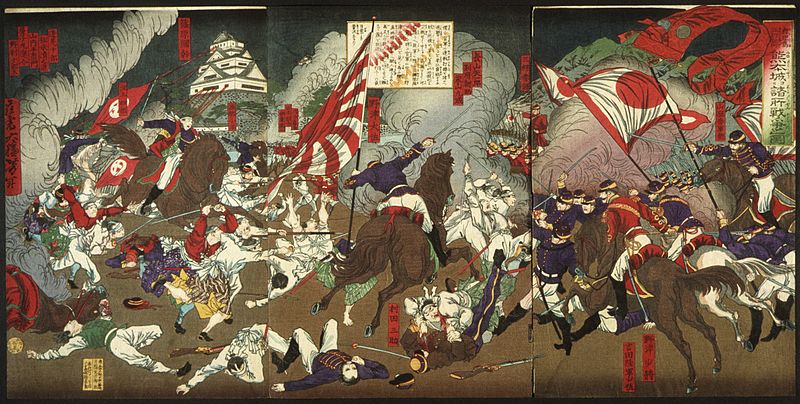

Under the leadership of Saigo Takamori, Satsuma’s army was built up to about 15,000 samurai, with the majority of them made up of students from Saigo’s military academies. They armed themselves with guns, as well as the traditional samurai swords.7 They then marched out of Kagoshima to begin their campaign. The Satsuma forces made their way to Kumamoto, the capital of the Higo province, north of the Satsuma province, arriving by the 20th of February. This city of 44,000 contained a castle, one that Saigo needed to take at all costs, in order to be able to march to the capital of Japan. It had stone and dirt terraces, intersected by moats and canals. Its curved walls were lined with turrets.8 It was one of the strongest castles in Japan. At first, the leader of the garrison at Kumamoto, Major General Tani Tateki, hoped to be able to defend the town, and he prepared for its defense, razing any houses near the castle, and digging in. Soon after the arrival of the Satsuma rebels, skirmishes started all around the castle.9 But by February 23, Tani ordered a retreat into Kumamoto castle, being vastly outnumbered by over 3 to 1, in the attempt to defend the entire town. His own numbers ranged around 3,800, with a number of policemen allowing the number to increase above 4,000.

This retreat into the castle allowed Saigo’s forces to attack the massive fortifications. They attempted to get into the castle by storming the walls, but they were repelled time and time again by the castle’s garrison, made up of conscripted peasants and armed policemen. This was a resistance the samurai didn’t expect, because the samurai saw the defenders as inferior to them and their lifelong training. Unable to keep up a long, high intensity battle, the Satsuma rebels dug in for a siege. The imperial soldiers picked off any rebels who tried to bring in field guns, and in time, Saigo’s forces were able to break through the gates with the few artillery pieces they were able to use. They were quickly taken care of by landmines, placed strategically in the path of charging samurai. During the lulls of the siege, the commoner forces in the castle were entertained by their fellow soldiers, while the samurai sat in their fortifications outside the castle. However, despite these disadvantages and failures, and despite the losses in the rebel forces, Saigo’s rebel army continued to grow. His cause, despite the vague main objective, “Talking to the government,” resonated with many disaffected samurai. Disaffected samurai from the Gakkōtō, a conservative group of samurai, joined Saigo’s forces by the thousands. Similarly, a group of samurai formed by radical students of the Ueki Gakkō, called the Kyōdōtai, also joined up with Saigo’s rebel forces. The press also began to cautiously support him, without committing illegal acts under the Meiji Government’s media laws. They created a slogan for Saigo, as well as bringing his rebellion into the mainstream media. Artists also began to draw him as a heroic figure.10 These groups of samurai, along with other volunteer rebels, caused Saigo’s forces to balloon to approximately double its previous size. With these troops, Saigo intended to continue the siege, committed to attacking the castle. However, the Imperial Japanese government had other plans.11

The imperial government, seeing the rebel uprising, scrambled its troops. The long siege allowed Imperial Japan to plan and execute its next move. With Saigo’s entire military force tied up at the siege of Kumamoto castle, they sent a force of 1200 infantry, 800 marines, and 700 armed police aboard three men-of-wars to Kagoshima. Despite likely expecting a fight, the Imperial Japanese performed their landing on the early days of March with little resistance. Empty of samurai, the army was able to take the governor of the city into custody, freed the spies who were taken prisoner, and stripped the city of any remaining gunpowder the army could find. Once these deeds were done, the army returned to Nagasaki, where they had embarked from, leaving Kagoshima in charge of a loyal family.12 Saigo had lost control of his home city, and more than four-thousand spare barrels of gunpowder, a massive loss. His army was now without a home city, with no cities near him, like Kagoshima, that he could reasonably go to without breaking the siege. Imperial Japan also sent a large force of imperial troops to relieve the castle that had been under siege since late February.13 In response to these relief forces, Saigo sent his own force to try and stop the Imperial forces from breaking the siege, leaving a few thousand at Kumamoto castle to keep it locked down. The two armies met at Tabaruzaka, a hill about twenty miles (or thirty-two kilometers) from the castle, and both had about 10,000 soldiers each. For the next eighteen days, the Imperial army launched assaults at Tabaruzaka hill, attempting to dislodge the rebels. The battle was a bloody one, with casualties of about 4,000 soldiers on each side. The rebels, despite the advantage of higher ground, were low on ammunition and were struggling to fight during pouring rain. The water made their flintlock weapons useless, and the Satsuma rebels were forced to resort to swords, engaging in close quarters combat to defend their position atop the hill. On the 18th day, after holding hill since March 3, the Imperial forces broke through, forcing the battered Satsuma rebels to retreat to the town of Ueki, to the east of the hill. They held their ground there until April 2, when they were forced out of the city. From there, the Imperial Army marched to Kawashiri, and defeated the Satsuma rebels there as well. This blow broke the siege of Kumamoto castle, relieving its forces, which by this point were severely depleted and had approximately 20% casualties. Saigo and the Satsuma rebels then fell back and regrouped at Hitoyoshi, holding there until May 27. After combat for three weeks, the Imperial army attacked the city in full, and Saigo once again was forced to retreat.14 From here on out, the rebellion became a staggered retreat for Saigo, with guerrilla warfare as the main tactic. An army of well-trained samurai had been broken and beaten back by peasants with rifles.

This victory was a decisive turn in the tide of the war in favor of Imperial Japan. The Imperial army had proved itself in battle, showing that a force of peasants could come out victorious over a trained, well-off samurai force. With the rebels now unable to fight the Imperial army with conventional means, they took to guerrilla warfare, going on a long, winded retreat through the mainland island of Kyushu. Saigo was no longer trying to reach Tokyo. That goal was out of the question with the Imperial army having the advantage. Instead, his goal was to get away from the Imperial army and return to their home cities. With the retreat, they lost their field guns and much of their ammunition. In many engagements, the samurai now resorted to swords, abandoning their guns due to this shortage of ammo. Saigo split his forces, likely to both go faster to stay ahead of the imperial army, and to avoid a single decisive battle. The few times Saigo and his Satsuma rebels turned to fight in conventional battles, like in the southern city of Miyakonojo where he sent a large majority of his forces to, they were defeated. Once the rebels in Miyakonojo were defeated, the Imperial forces turned back north to pursue Saigo to Nobeoka, a coastal city in the eastern section of Kyushu, where Saigo and his troops once again fought the Imperials in mostly conventional combat on August 10. His 3,000 troops, however, were not only outgunned but vastly outnumbered by almost six to one against the Imperial army. Despite holding off for a week, the samurai were yet again beaten back by conscript peasants, and were pushed westward to a mountain range. There, the Imperial army attempted to encircle and destroy the Sastuma rebels on August 18, but Saigo and his rebels, amazingly, escaped the encirclement by getting through a thick forest, yet again on the run.15

After escaping the encirclement, on September 1, Saigo was able to slip back into Kagoshima. He had only a few hundred samurai with him. These samurai were the last remnants of Saigo’s tens of thousands strong force that he previously had. There in the Sastuma province, he set up at mount Shiroyama, a hill near Kagoshima. Trapped with nowhere to go and with ever dwindling supplies, it was here that Saigo and the Satsuma rebels planned to make a final stand. On September 23, the commander of the Imperial forces, General Yamagata, sent a letter to Saigo Takamori, asking him to abandon his struggle. In General Yagamata’s view, there was nothing left to gain from fighting, and that Saigo Takamori had already proven his valor and honor through this struggle. There was no response.16 On their side of the mountain, the Imperial army wasted no time setting up defenses. Earthworks were raised, trenches were dug, men were sent to cover these new defenses, and by September 10, mortar-batteries were set up along these earthworks. Bombardments on the saumurai positions began, and the shelling killed a couple hundred Satsuma rebels before they could even react in a strong fashion. The shelling also allowed the Imperial forces to creep ever closer, while the Satsuma rebels were essentially powerless to stop them, with feigned attacks tiring the samurai and making them lower their guard, even as the imperial army was at their doorstep. The shelling continued for weeks, and on the 24 of that month, it only intensified in strength. Shells poured onto the Satsuma rebels before dawn. With the darkness hiding their movements, the Imperials quickly ascended the slopes of the hill and surprised the rebels, who were not ready for an actual attack after the feints they endured before. The battle quickly swung in favor of the Imperial soldiers, with the samurai having to fight with swords and the occasional small arms. Saigo was among one of the first to fall. Mortally wounded, he was dragged away by one of his closest friends. Likely unable to commit seppuku because of his wounds, his head was cut off by his friend, before he rejoined the battle.17 By 6 AM, at dawn, only forty samurai remained. Accepting death, they charged down the hill in one last rally. The Satsuma rebels, with their swords and the bushido code, were cut down by the gunpowder weapons of the Imperial army. With the end of the battle, the age of the samurai had officially come to an end. The peasant army they despised were the ones standing victorious, on a hill littered with the bodies of men clinging onto a dying era.

The battle of Shiroyama resulted in only thirty dead on the side of the Imperials, and the entire few hundred samurai holed up in Shiroyama. But the rebellion as a whole saw Japan, both the rebels and the Imperial forces, take over 25,000 in casualties. 13,399 people were killed, and 21,523 were wounded. Like in all wars, however, many of the wounded would later die of their wounds. Many towns that saw fighting between the Imperials and Saigo’s rebels were met with destruction. The wooden houses were easily destroyed by the mortars and artillery of the Imperial Japanese and the guns of the samurai before their retreat. Kumamoto was reduced to ash, and Kagoshima was almost entirely turned to rubble.18 The Satsuma Rebellion was a rebellion where the samurai, and their way of life, met their end. The newly victorious Imperial army had effectively proven its strength, usefulness, and power in a trial by fire, defeating one of the three great nobles that helped create it. Saigo Takamori and his samurai died in the rebellion, but the spirit they created lived on. Saigo Takamori today is hailed as a popular hero in Japan. He remains an example of loyalty, honor, and pure motive.19 The code of the samurai was also inserted into the new Imperial army. An army made up of all classes and of people from all backgrounds, they were to continue the ideals that Saigo and the samurai had left behind, in a force now under one banner.

- Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 4th edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 86. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, 1st edition (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 194-195. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, 1st edition (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 198. ↵

- The daimyos were the great lords who were vassals of the shogun in feudal Japan ↵

- Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 4th edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 85. ↵

- Augustus Henry Mounsey, The Satsuma Rebellion: An Episode of Modern Japanese History (Forgotten Books, 2018), 127-130 ↵

- Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 4th edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 86. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, 1st edition (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 203-204. ↵

- Augustus Henry Mounsey, The Satsuma Rebellion: An Episode of Modern Japanese History (Forgotten Books, 2018), 144 ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, 1st edition (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 205-206. ↵

- Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 4th edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 86. ↵

- Augustus Henry Mounsey, The Satsuma Rebellion: An Episode of Modern Japanese History (Forgotten Books, 2018), 150-152. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, 1st edition (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 207. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, 1st edition (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 207-208. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, 1st edition (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 208-209. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, 1st edition (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 210. ↵

- Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 4th edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 210-215. ↵

- Augustus Henry Mounsey, The Satsuma Rebellion: An Episode of Modern Japanese History (Forgotten Books, 2018), 233-234. ↵

- Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 4th edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 86. ↵

14 comments

Ben Kruck

This an interesting article. The samurai are an important part of Japanese culture, but it feels like that they aren’t discussed much. I actually thought the samurai ended much earlier than that, it’s interesting that they ended in the nineteenth century instead. The samurai may have died physically, but their spirit ended up into the new imperial army, with some of their teachings transferring over as well.

Jordan Davenport

There is so much history about Japan and the Samurai, this article is very well done. So many historical details and the structure makes it come alive. This battle was everything for the samurai, not just their lives, but their culture and way of life. This also shows that no matter what surrender was not what the samurai believed. They fought until the very end, a powerful fighting spirit that lives on in the course of history.

Steven Valdez

This was such an excellent article! As far as I can remember, I have always been fascinated by the history of samurai. You did such an awesome job detailing their battle tactics and how far they would go to win battles. The samurai were always such extraordinary people and it was nice to read an astonishing story on events such as this. The Japanese Art you included made your article even more interesting to read about!

Gabriella Parra

I feel like samurai are a well-known part of Japanese culture, but we never truly dive into their history. It’s amazing that the samurai died but their spirit lived on in the Imperial army. This story was fascinating, and I enjoyed seeing the Japanese art while I read (especially because it’s so different from western art) thanks to your use of images. Congratulations on such a great article and your nomination!

Jesslyn Schumann

Hi Matthew! First, congratulations on your nomination. The detail within the article was probably the best I have read thus far. It really allows for someone like me, who has almost no knowledge of this topic, to really understand what happened during this tragic time. I think it is so interesting that though they died in the war, their ideas have been carried on and their legacies remains to this day. Good luck with the awards!

Justine Ruiz

I loved reading this article because I have always been fascinated with history. I had never known about the background of the sumuari nor even thought about how they were extinguished. It was intriguing to read about this rebellion! Great article!!

Chris Ricondo

Congratulations on the nomination and on such a well-written essay. So learning about Saigo Takamori and his insurrection was fascinating. It’s a shame that the samurai’s faith was shattered in war, but I have a great deal of respect for the samurai because of their life codes.

Mauricio Rebaza Figueroa

Excelent article! I really had no clue about this topic before reading your project. This story and how you wrote about it made it a really interesting topic to read about. The sources you used were really good and strong to help with the trust-worthiness of your article. You also used used really good images that helped me while reading. Overall, you did a really good job.

Andrew Ponce

This article really tells the interesting and true aspect of not only the warrior aspect of East Asia, but the cultural aspect of Japanese culture. Many people get their information on samurais and aisan culture through movies, however this article goes into depth with how and why the samurai was important to its people. Not only this, but also in a way that engages the reader and utilizes images to help the reader along with the story they are telling. Great job, and congratulations on the nomination!

Phylisha Liscano

Hello Matthew, great article, and congratulations on the nominations for best descriptive article and best in political history. This was a very well-written article and I really enjoyed reading your article. I knew a little about samurais but I did not know the whole story pertaining to the Satsuma Rebellion. A very interesting article and I enjoyed getting to read about the Satsuma Rebellion. Overall excellent article.