On March 14, 1903, John Muir received a letter. This wasn’t an unusual event for the famous naturalist. People wrote to him all the time, sharing with him their love for nature and reveling in his wisdom. However, this was an exceptionally important letter. It was from President Theodore Roosevelt.

“Our generation owes much to John Muir.” —Theodore Roosevelt1

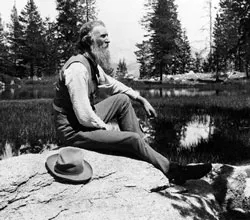

John Muir grew up with a father hardened by years of poverty. Scolded for any form of childish behavior in the house, Muir turned to the wilderness for solace. It was there, in the rocky cliffs of Dunbar, Scotland, that his love for nature was born.2 In school, Muir would devour any book about nature he could get his hands on. One night, as he was attending to his schoolwork by the fire, learning about bald eagles and gold in the US, his father told him he didn’t need to study those things anymore, for they’d be moving to America in the morning. The voyage across the Atlantic was long but filled with joyous anticipation for the “wonderful schoolless bookless American wilderness.”3

Muir loved his new farm home in Wisconsin and spent his days marveling at the all-encompassing nature around him. He kept busy with chores but made time for working on gadgets, becoming a prominent inventor. He went to university, but not for a degree; he went simply for the joy of learning, only taking classes that interested him. However, soon the walls of college became too claustrophobic, and Muir longed for real-world experience. He said, “I was only leaving one University for another, the University of Wisconsin for the University of the Wilderness.”4 Muir set off for Canada, taking up odd jobs to get by.

Later, while in Indiana working at a carriage company, he suffered a traumatic injury. As he was trying to tighten a leather belt on a machine, his tool slipped and punctured his cornea. Muir became blind. He was ordered to lie in a dark room to recover, and was shocked by how the damage to his eye affected his entire body; he was confined to bedrest and couldn’t even eat for the first few days.5 After a month-long miraculous recovery, Muir set his sights on nature. He knew what it was like to be deprived of the beautiful scenes the world offers, and he didn’t want to miss out on a single breathtaking view. Thus began his time of wandering, as he made his way from Indiana all the way to Florida by foot. He never made a plan, instead vowing to take the route least traveled.

After completing his pilgrimage, he wanted to journey further to South America, so he picked up a job working at Hodgson Mill to save up for the trip. Unfortunately, just three days after starting, he contracted malaria. Muir lived in a delirious state for months. The Hodgson family was benevolent and nursed him back to health. Muir has said he owed them his life. One evening, giddy with the delight of recovery, he climbed onto their roof to watch the sunset. There, he spotted a ship in the distance. After inquiring with locals, he learned it was soon headed to Cuba. The Hodgsons knew of his wish to travel to South America, so with their support, Muir was able to board, and he sailed for the first time since his fateful childhood trip to the United States. He landed in Havana and spent four weeks studying the plants of the island, spending countless hours in the botanical garden examining agave, and even more on the shores inspecting beach purslane.6 Unluckily, Muir contracted malaria yet again. He decided the humid climate was not doing him any good, and resolved to relocate somewhere drier. This caused him to end up in the desert of California. While there, he recovered, and immediately fell in love with the Sierras, which he described as “the most divinely beautiful of all the mountain chains.”7 He built a cabin nestled in a meadow near Yosemite Falls, and though he went on to travel the world, he always found his way back to California.

Muir went on to publish many articles about his studies and became a world-renowned naturalist. Through his efforts, Yosemite National Park was created, along with Sequoia, Mount Rainier, Petrified Forest, and Grand Canyon. In 1901, he released the book Our National Parks, a collection of his notes on those parks. It was published when industrialization was finding its footing in American society and helped persuade people to consider wilderness conservation more seriously. One of the people put under the spell of Muir’s writing was President Theodore Roosevelt.

Theodore Roosevelt grew up wealthy in New York City. He had access to a lavish education and went on trips abroad with his family often. He constantly pushed himself, becoming very athletic and physically fit, as well as assertive and intelligent. He had a flair for the dramatic and attracted a lot of attention as the youngest member of New York’s legislature. His flaws were as equally apparent as his virtues, but this transparency only attracted people to him more. When his wife died after recently giving birth to their daughter, Roosevelt retreated into nature to find solace. He spent two years recovering in the wild and wrote about his observations. When in New York again, he jumped back into the political sphere, making his way up to Vice President. The president, William McKinley, was assassinated, and Roosevelt was catapulted to the position, becoming the youngest to ever hold it.8 A few years after his inauguration, Roosevelt read John Muir’s book Our National Parks, and immediately sent him a letter, asking Muir to guide him through his favorite park, Yosemite. Roosevelt’s letter said, “I do not want anyone with me but you, and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.”9

Muir was reluctant at first. He already had a different trip planned for Europe, and wasn’t keen on the idea of having to babysit a government official in the woods. However, it’s not every day you get the opportunity to camp with the president. Of course, he had ulterior motives; Muir wanted to push for environmental protection laws. Regardless, Roosevelt had ulterior motives too. He had read about ranchers and developers destroying the wilderness for their own use, but wanted to see for himself if the land’s resources could really be depleted so easily. Not only that, but he was going on a campaign tour in California.10

Roosevelt wanted to be alone with Muir, but that was just not feasible for a president. After a long debate, Roosevelt was able to convince his staff to only make two men accompany them, along with three pack mules to carry supplies and no security. On May 15, 1903, they all arrived in Yosemite National Park. The journey to get there was not the smoothest, literally. The train didn’t go all the way to the park, so they had to ride in a bumpy stagecoach for ten hours. Roosevelt was in awe but exhausted from the journey, so the pair had a relatively quiet night. A large dinner was prepared, and then forty blankets were laid on the ground for Roosevelt to sleep on. Muir slept on a small cloth from his knapsack and covered himself with branches for warmth. Neither used a tent, and they were thankful for the stunning clear sky.11

While traversing the wilderness via horseback on the second day, a huge snowstorm started. Muir and Roosevelt were pelted with icy flakes on their way to Sentenial Dome, a granite cliff known for a pine tree that grew on its peak. They braved the assault until near its base, where they decided to make a camp in a meadow, surrounded by silver fir trees. Muir built a large fire, and Roosevelt sat with him, the two bonding over the adventure of the day, and regaling each other with other audacious stories of their own.12

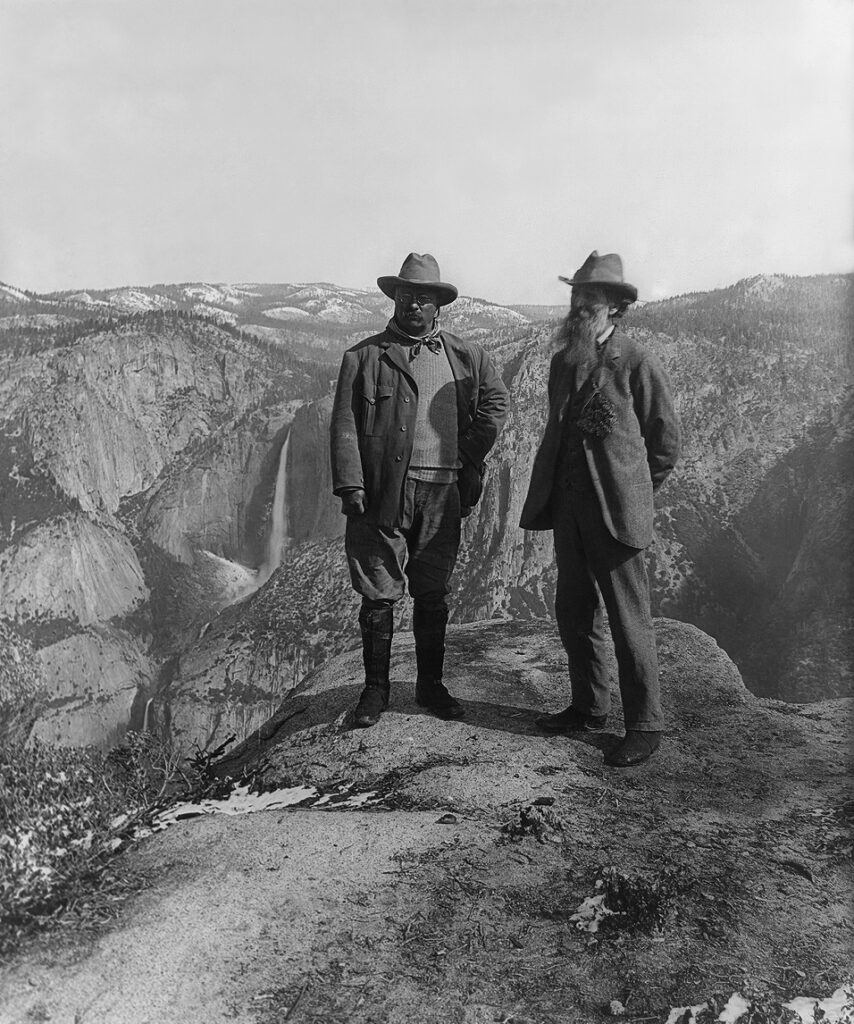

The morning of the third day was Roosevelt’s favorite; he recalled waking up covered in a thin layer of snow and looking around to see icy branches glistening in the light of dawn. The four men traveled on horseback to Glacier Point, a spectacular viewpoint featuring a rock that hung over the edge. It’s said that Roosevelt, upon arriving there and looking down over the valley, experienced such overwhelming joy that it brought him to tears—the President, crying over the beauty of nature. There, a photographer was waiting for the crew, and the most famous picture of Roosevelt and Muir was taken.13

The famous duo encountered multiple groups of people crowded together at popular spots trying to catch a glimpse of them. However, this trip meant a lot to Roosevelt, and he did not want to turn the park into just another backdrop for his presidential campaign. So, instead, he chose to remain cut off from the outside world for one more night. Dodging the crowds, the crew ended up on the valley floor, setting up camp with a dramatic view of El Capitan, a granite monolith. Throughout the trip, Muir and Roosevelt rarely stopped talking, whether it was while hiking or in between bites of supper. Muir shared all the knowledge he’d acquired over the years about the trees, wildlife, and geology. Roosevelt later said that “John Muir talked even better than he wrote.”14 Muir, speaking of Roosevelt in a letter to his wife, wrote, “I never before had a more interesting, hearty, and manly companion.”15 The pair became close over the trip, but that doesn’t mean they always agreed. One day, when Roosevelt was telling Muir a hunting story, Muir snapped, calling him immature because of his fondness for killing things. Roosevelt conceded in the moment, but never changed his mind about hunting. Luckily, he was able to be persuaded into other things, the things Muir truly wanted: protection and conservation. That final night, seizing his last opportunity to have a fireside chat with the President, Muir pushed his agenda of political action onto Roosevelt.16

Roosevelt was won over. Whether it was the giant trees reminiscent of cinnamon sticks, the breathtaking aerial view of the greenery colliding with the granite, or Muir’s whimsical way with words, something clicked for the President, and he became hell-bent on the conservation of nature and preservation of its beauty. The next day, he arrived in Sacramento and gave a speech there, saying,

“In California, I am impressed by how great the state is, but I am even more impressed by the immensely greater greatness that lies in the future, and I ask you that your marvelous natural resources be handed on unimpaired to your posterity. We are not building this country of ours for a day. It is to last through the ages.”17

He further showcased his commitment by sending a telegraph to the Secretary of the Interior that night, asking for federal control of Yosemite and granting Muir’s wish to expand its borders to include Mariposa Grove and other forest areas along the region.18

Unfortunately, Roosevelt’s commitment to preserving the unspoiled beauty of Yosemite National Park began to diminish after a devastating earthquake occurred in San Francisco in 1906. Though the quake lasted less than a minute, the damage was intense and caused several fires that burned for days. It killed 3,000 people and left half the metropolis population homeless.19 Congress reacted with an outpouring of aid to the city, and officials began planning how to rebuild essential infrastructure, such as water and power. An idea was proposed to construct a dam in Yosemite, to turn the Hetch Hetchy valley into a reservoir. Muir was vehemently against this recommendation. As the debate continued, Muir wrote to Roosevelt, imploring him to protect Hetch Hetchy. Roosevelt responded that he’d do everything in his power to do so. However, most people in politics did not care about the protection of Yosemite the way he did, and the conservation of the valley was becoming an unpopular opinion. In 1908, Roosevelt sent a crushing letter to Muir, saying “I must see that San Francisco has an adequate water supply… the greatest good for the greatest number of people.”20 Five years after the camping trip, President Theodore Roosevelt signed off on damming the Tuolumne River and flooding Hetch Hetchy Valley, dramatically changing Yosemite National Park forever.

Muir and other preservationists were incredibly upset with the decision and used this new example of a martyred landscape to bolster their position, effectively blocking plans to build dams in Grand Canyon National Park and Dinosaur National Monument. Muir continued fighting for environmental issues until his untimely death in 1914. Less than two years later, the National Parks Service was created. He never got to see his dream come to fruition. Yet, not all was lost. Muir was able to witness other incredible changes while he was alive, specifically, those enacted by Roosevelt. He may have disappointingly chosen infrastructure over preservation when it came to Yosemite, but he was a champion for nature nonetheless, establishing 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, 4 national game preserves, 5 national parks, and 18 national monuments. In total, he protected over 230 million acres of public land.21

It is undeniable that the 1903 camping trip between John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt changed the course of American history. As demonstrated, nature has the power to change everything. Sometimes all that’s needed is a guide. Someone who can point out all the wonders of the world and revel in their beauty with us. Muir was that guide for Roosevelt, I am that guide for my friends and family, and you can be that guide for others. Our generation has to be that guide for the people in power who have the final say between conservation and disregard. We must always push for conservation, just as Muir did, before there are no wild places left to go on life-changing camping trips.

- Theodore Roosevelt, “John Muir: An Appreciation,” Outlook 109, (1915). ↵

- John W. Bailey, “John Muir,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2022, https://discovery.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=fc2ea33a-b7ce-3e40-9405-e376f011156c. ↵

- John Muir, The Story of My Boyhood and Youth (Houghton Mifflin, 1913), 55. ↵

- John Muir, The Story of My Boyhood and Youth (Houghton Mifflin, 1913), 287. ↵

- Stephen J. Taylor, “Misc Monday: John Muir’s Vision Lost and Found – Historic Indianapolis: All Things Indianapolis History,” Historic Indianapolis | All Things Indianapolis History, 2017, https://historicindianapolis.com/misc-monday-john-muirs-vision-lost-and-found/. ↵

- John Muir and William Frederic Badè, A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916), 164-166. ↵

- Harold Wood, “John Muir: A Brief Biography,” John Muir Biography – John Muir Exhibit, 2023, https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/life/muir_biography.aspx. ↵

- William I. Hair, “Theodore Roosevelt,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2023. ↵

- Ellen Terrell, “Roosevelt, Muir, and the Camping Trip: Inside Adams,” The Library of Congress, 2016, https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2016/08/roosevelt-muir-and-the-camping-trip/. ↵

- Ellen Terrell, “Roosevelt, Muir, and the Camping Trip: Inside Adams,” The Library of Congress, 2016, https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2016/08/roosevelt-muir-and-the-camping-trip/. ↵

- Timothy J. Curry and Kierman O. Gordon, “Muir, Roosevelt, and Yosemite National Park as an Emergent Sacred Symbol: An Interaction Ritual Analysis of a Camping Trip,” Symbolic Interaction 40, no. 2 (2017), 248 ↵

- Timothy J. Curry and Kierman O. Gordon, “Muir, Roosevelt, and Yosemite National Park as an Emergent Sacred Symbol: An Interaction Ritual Analysis of a Camping Trip,” Symbolic Interaction 40, no. 2 (2017), 249-251 ↵

- Timothy J. Curry and Kierman O. Gordon, “Muir, Roosevelt, and Yosemite National Park as an Emergent Sacred Symbol: An Interaction Ritual Analysis of a Camping Trip,” Symbolic Interaction 40, no. 2 (2017), 251-253 ↵

- Theodore Roosevelt, “John Muir: An Appreciation,” Outlook 109, (1915), 27-28 ↵

- Peter Carlson, “TR Goes Camping with John Muir: The Few Days the President Spent Roughing It with the Naturalist Led Directly to the Protection of Vast Swaths of Forest Lands,” American History, (2016), 14 ↵

- Timothy J. Curry and Kierman O. Gordon, “Muir, Roosevelt, and Yosemite National Park as an Emergent Sacred Symbol: An Interaction Ritual Analysis of a Camping Trip,” Symbolic Interaction 40, no. 2 (2017), 253-256 ↵

- Timothy J. Curry and Kierman O. Gordon, “Muir, Roosevelt, and Yosemite National Park as an Emergent Sacred Symbol: An Interaction Ritual Analysis of a Camping Trip,” Symbolic Interaction 40, no. 2 (2017), 257 ↵

- Ellen Terrell, “Roosevelt, Muir, and the Camping Trip: Inside Adams,” The Library of Congress, 2016, https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2016/08/roosevelt-muir-and-the-camping-trip/. ↵

- “San Francisco Earthquake, 1906,” National Archives and Records Administration, https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/sf. ↵

- Timothy J. Curry and Kierman O. Gordon, “Muir, Roosevelt, and Yosemite National Park as an Emergent Sacred Symbol: An Interaction Ritual Analysis of a Camping Trip,” Symbolic Interaction 40, no. 2 (2017), 258-260 ↵

- “The Conservation Legacy of Theodore Roosevelt.” U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021, https://www.doi.gov/blog/conservation-legacy-theodore-roosevelt ↵

2 comments

Andrew Ponce

The title of this article already captures the reader, as it gives little context as to what the article contains; however, it entices the reader to learn more about it. This article also begins with a captivating fact, mentioning one of the greatest presidents in the country’s history. This article does more for the reader logistically and fundamentally. Teaching the reader about historical events, while also providing an easy and interesting flow of rhetoric that allows the reader to easily understand the information. Amazing work on this publication.

Sudura Zakir

Awesome article and I really liked the images here. Those reflect the story much better and lots of sources give a strong impression on your writing. Mentioning Roosevelt as a major character besides Muir made the context more interesting because I am familiar with Roosevelt but not Muir. I enjoyed the whole campaign story and the title was a major hook to your article which drew my attention to read it. Nice work!!!