It’s May of 1916, war rages across the world as Great Britain and her allies are locked in a life or death struggle against the mighty German Empire. Chaos and death reign on the battlefields of France and Russia. However, separate from the carnage of trench warfare and No Man’s Land, lie two powerful forces: the British and German fleets.1 The British Grand Fleet consisted of thirty-three dreadnought battleships, the most powerful ships that had ever been built, and over one hundred other smaller vessels; it was the most powerful fleet in the world. The German High Seas fleet consisted of eighteen dreadnought battleships and was supported by over one hundred smaller vessels as well, and it was second only to the British fleet. For the duration of the war, the two sides had waited with bated breath for an opportunity to engage each other. Finally, at the close of May 1916, that opportunity presented itself.2

At the end of May 1916, the British government became aware that the German High Seas Fleet was planning a major operation. They did not know where it would take place, but, at noon on the 30th, the government ordered the Grand Fleet to proceed to the North Sea. Commander of the fleet Sir John Jellicoe and his second in command, Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty, jumped into action immediately upon receiving orders. They sent signal flags up the mast of their ships indicating to the fleet that combat orders had been received. Immediately, the naval base at Scapa Flow was filled with the sights and sounds of blowing whistles, rowboats moving to and fro delivering crew members to their assigned ships, and black smoke billowing out of the funnels of the great steel behemoths. By nine that evening, the Grand Fleet was ready to put to sea. Altogether, Jellicoe and Beatty commanded a force of 150 ships, including 28 dreadnought battleships and 9 battlecruisers. It was an extremely powerful force.3

Meanwhile, across the North Sea at the German port of Wilhelmshaven, the High Seas Fleet was making its own preparations to put to sea. Commander of the High Seas Fleet, Reinhard Scheer, had been waiting for weeks for the opportunity to sail his fleet into the North Sea. Finally, with the opportunity at hand, Scheer had prepared 16 dreadnoughts along with 5 battlecruisers. In all, his fleet numbered just 99 ships, but the Germans were not to be underestimated, as they were extremely skilled seamen. One hour past midnight on the 31st of May, the High Seas Fleet was at sea, steaming north to hunt for the enemy fleet. So it was that the two most powerful fleets in the world were now on a collision course, each vying for a decisive victory, but only one side could win.4

The rivalry between the British and German navies can be traced back to the 1880s. When Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany ascended to the throne in 1888, Germany’s foreign policy changed considerably. Before Wilhelm’s accession, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had been content with Germany’s place as the leading power on the European continent. However, the new Kaiser had a different idea for Germany’s place in the world. He believed that the German Empire should be the greatest nation, not just on the continent, but also in the world. To achieve that goal he needed one thing, a powerful navy. Since he was a small child, Wilhelm dreamed of a navy that he could be proud of. All the way back to his holidays at Osborne House in England with his grandmother Queen Victoria, the Kaiser remembered the beautiful ships of the Royal Navy at Portmouth. Now, as emperor of Germany, he had the opportunity to build his own fleet, and in doing so, increase the power of his nation. Within four months of the beginning of his reign four new battleships were ordered. Thus, the German navy began to grow, but it was not the Kaiser who would catapult the German Navy to first rate status; rather, it was a man by the name of Alfred Tirpitz.5Alfred Tirpitz, “The Father of the German Navy,” was at one time a mere sailor in the fledgling German fleet. No one could have imagined that he would become the most important figure in German naval history. However, his fortune changed, dramatically, at a dinner party in 1890 when Kaiser Wilhelm asked Tirpitz what his vision for the future of the navy was. When Tirpitz replied, “Germany must have battleships,” the Kaiser became so enthusiastic that nine months later he asked Tirpitz to become Chief of Staff to the High Command, and to develop a strategy for a new German fleet.6 From that moment on, Tirpitz’s star was on the rise, and by June of 1897, he was appointed Navy Minister. It was in this role that Tirpitz would transform the German navy into a force to be reckoned with.7

Immediately upon entering office, Tirpitz delivered a memorandum to the Kaiser entitled “General Considerations on the Constitution of Our Fleet According to Ship Classes and Designs.” In it he stated that Great Britain was the most dangerous enemy in regard to Germany, and that the new German fleet must be powerful enough to challenge the Royal Navy. Tirpitz believed that in order to challenge the Royal Navy, nineteen battleships would have to be built within nine years. The implications of this memorandum were extraordinary. Britain had been designated as the enemy of Germany, and this was the main reason for the construction of a new German fleet. Tirpitz then launched a public relations campaign in which he successfully convinced not only the German Parliament, but also the German people that a powerful fleet was a necessity for national defense. Finally, in March of 1898, the German Parliament passed the 1898 Naval Bill, which set aside funds for the construction of nineteen battleships. It was a huge success, but it was clearly not enough, and in 1900, a second Naval Bill was passed that set aside more funds for an additional nineteen battleships. The new Naval Bill set Germany on a very dangerous path: a collision course with Great Britain.8

Indeed, the British government had been watching developments in Germany with increasing alarm. When the second Naval Bill was passed it felt like an insult. The whole existence of Great Britain depended on her mastery of the seas, and the nation had always prided itself on having the world’s greatest navy. Now, Germany was poised to take that distinction from her. The British government was not going to sit idly by as the Germans usurped their position as the leading naval power. Under the direction of First Sea Lord, Jacky Fisher, the British government, weary of German naval expansion, consolidated its battleships closer to Great Britain. Also, Fisher oversaw the construction of H.M.S Dreadnought, the revolutionary vessel that became the model battleship for every other navy in the world. After that, Britain and Germany became embroiled in building bigger and better battleships, preparing for the battle they knew was coming.9

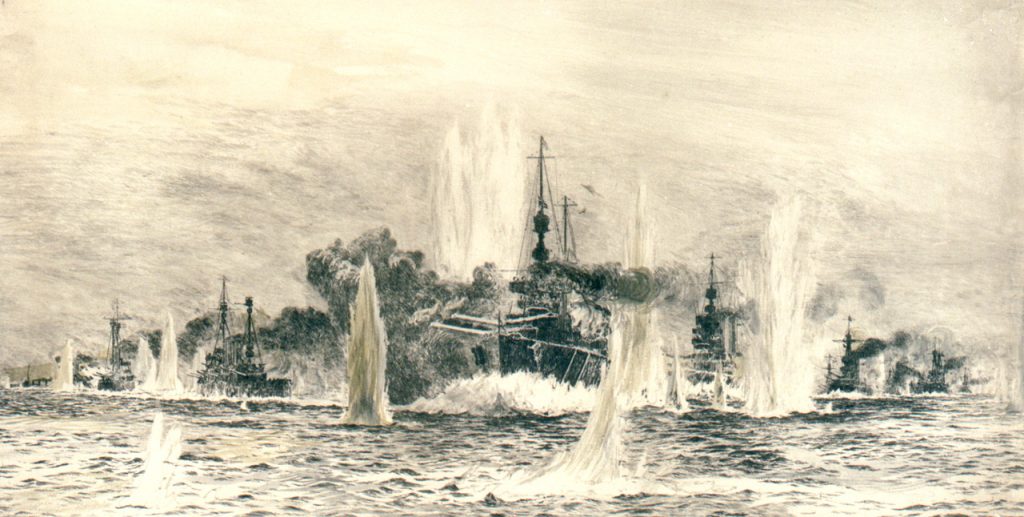

As dawn broke on the morning of May 31st, the British fleet divided into two squadrons that were seventy miles apart. Admiral Beatty’s squadron included six battlecruisers and four battleships, while Admiral Jellicoe commanded the rest of the fleet. For hours Beatty’s squadron sailed ahead without encountering the enemy, but that all changed at 2:20 in the afternoon, when the British destroyer Galeta sighted two German cruisers. At 2:28 Geleta open fired, and the first shots of the Battle of Jutland were out. Beatty reacted quickly, with the signal “Action Stations,” and the crews of the vessels began preparing for action. Men rushed to and fro pulling out fire hoses and stocking water, food, and other provisions in gun turrets. Within minutes, the decks of the entire squadron had been cleared, and the men were hunkered down inside the gun turrets ready for action. At 3:45 Beatty arranged his ships into a line of battle. All of his battlecruisers followed each other at five hundred yard intervals, and the four battleships followed seven miles behind. The German forces, too, had arranged themselves in a battle line, and they got the first shots out against their opponents. The Germans were on target almost immediately, and their shells struck the British battlecruisers with metal shattering force. After ten minutes, Beatty’s forces finally found their targets, and began scoring hits. Finally, both sides had engaged; the sound of their guns rang out across the sea like thunderclaps; it was truly a clash of the titans. 10At 4:05 disaster struck the British squadron. The battlecruiser H.M.S Indefatigable had been engaged with the German vessel, Von der Tann, and had suffered significant damage. Finally, the German battlecruiser fired two last shots that penetrated her superstructure, and thirty seconds later she blew up. The wreck of the battlecruiser belched flames and smoke, and the vessel rolled over on her side and sank, taking with her 1,017 people. Only two crewmen survived. However, there was barely time to comprehend that loss, when H.M.S Queen Mary, beleaguered by the fire of two German vessels, exploded and was also engulfed by fire and smoke. At the same time there was a false report that another battlecruiser had been destroyed, at that Beatty uttered the famous phrase, “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.”11 Indeed there was something wrong with the British battlecruisers that day.12

Beatty’s luck changed at 5:45 that evening, when he spotted the rear guard of the Grand Fleet. Now it was the Germans turn to get the shock of their lives. When the High Seas fleet pursued Beatty, they had had no idea that he was leading them straight into the entire Grand Fleet. Indeed, Jellicoe had had enough foresight to arrange every single one of his ships into a single battle line. When the German fleet emerged from a smokescreen, it saw laid out before them almost every vessel in the Grand Fleet. The full power of the Grand Fleet now opened up on the High Seas Fleet. However, Admiral Scheer, commander of the High Seas Fleet, never panicked. Instead, he ordered his smaller vessels to pop smoke screens while the battleships turned away. However, Jellicoe was relentless, and he pursued the High Seas Fleet, crossing in front of it once more, allowing his ships to continue firing. There was, however, one thing Jellicoe was apprehensive about: a torpedo attack. With the Germans on the run, Jellicoe thought that Scheer might order a torpedo attack to guard the German retreat. With this in mind, Jellicoe elected not to follow the High Seas Fleet, which was in retreat. Still, throughout the evening, the Grand Fleet continued to search for the German fleet, and even though it was spotted multiple times, no orders were given to pursue the enemy.15 By June 2nd both fleets returned to their bases to assess their damages. In all, British major losses included the battlecruisers Indefatigable and Queen Mary, and also a third battlecruiser that had met the same fate as the others later in the battle, the Invincible, and three other large vessels along with eight smaller vessels. The German fleet suffered too. They had lost three large ships, including the battlecruiser Lutzow and the old battleship Pommern along with eight smaller vessels.16 Causalities were also high. The British lost 11,163 men, while the Germans lost 2,551 men.17

The Battle of Jutland was a quagmire. For the British, it forced them to accept the fact that the German Navy was an extremely powerful opponent, and that they had matched the British blow for blow. The improper storage of cordite was also an issue that had to be addressed. It appeared as if the commanders of the fleet had allowed their subordinates to disobey safety regulations, a practice that had to be put to an end. Still, British sea power was not compromised. All of the fleets’ battleships had survived, and Scheer had retreated multiple times during the course of the battle, and retreating does not win battles. The Germans, at first, hailed the Battle of Jutland as a victory, but the reality was far different. Great Britain’s fleet was still intact, and control of the North Sea remained firmly in British hands. Both sides were forced to admit that the Battle of Jutland was not the decisive battle they had been planning for for decades. However, Jutland was the most significant naval battle during the war, and it had a profound effect on both the British and German navies.

- World War I Reference Library, 2002, s.v. “The War at Sea.” ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 566. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 575-577. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 563-564. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War (New York: Random House, 1991), 76-77, 150, 163-164. ↵

- Alfred Tirpitz, quoted in Robert K. Massie, Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War (New York: Random House, 1991), 168. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of Great War (New York: Random House, 1991), 168, 172. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War (New York: Random House, 1991), 177-180. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War (New York: Random House, 1991), 461-462. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 579, 583-593. ↵

- David Beatty, quoted in Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 596. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 593-596. ↵

- Nicholas A. Lambert, “Our Bloody Ships” or “Our Bloody System”? Jutland and the Loss of the Battle Cruisers, 1916,” The Journal of Military History, Vol. 62, No. 1 (Jan., 1998): 29-55. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 597-603. ↵

- Norman Friedman, Fighting the Great War at Sea: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2014), 165-172. ↵

- Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 665. ↵

- John Campbell, Jutland: Am Analysis of the Fighting (London: Conway Maratime Press, 1986), 338-341. ↵

25 comments

Sara Guerrero

I’ve heard of the British Navy being very powerful, but I didn’t imagine the Germans having a powerful navy as well. I think this battle really tried to settle which European navy was the most powerful. I can see how Germany was underestimated greatly and even though at first Germnay declared the Battle of Jutland they soon realized the British Navy was still intact. I think this article was well thought-out and well-researched. Great job!

Antonio Holverstott

The German Empire and the British Empire had the world’s best naval resources in both commercial and military fields. The German naval forces under Kaiser Wilhelm II started to become stronger in order to fulfill the kaiser’s vision of a supreme German state fueled by his prideful nature. The British fueled by a sense of insecurity from the growing size and strength of the German navy reacted angrily at these changes.

Aiden Dingle

I think that the battle of Jutland was an interesting battle of the First World War.It was kind of a shock for the British Navy, they expected to have absolute victory over the German Fleet but lost in the end. Although losses were high for both sides, I think that the win would have to go to the Germans. This battle would really show what would happen for most of World War 1. Everyone really underestimated Germany just like during this battle and they Germans were able to take so many victories during the early war.

Samuel Vega

This is a well written article. The opening catches your attention with comparing the land and sea battles. The article then gives detail for both the navies of Germany and Great Britain. I did not know how Germany was building their navy and at that time declared Great Britain an enemy. During the war, both countries wanted to show dominance. The Battle of Jutland should have been that battle to declare the leader of the sea; but it was inclusive who won after the battle. Winner or loser; but countries experienced significant loss.

Aaron Peters

I found it pretty incredible how German Navy was able to put up a decent struggle against the British Royal Navy, who’s empire at the time nearly spanned a quarter of the planet’s land area, and also employed the largest navy. It shows how the growing power of the German Empire was one of the main issues which helped lead to the First World War.

Kenneth Gilley

This is a very well-written article! It is interesting to note that the British sailors’ neglect of safety precautions cost them so dearly. I am sure that the Battle of Jutland was a major blow to British morale. They had to except that they were no longer the world’s dominant naval power. On the other hand, the German’s gained very little out of the battle, themselves.

Michael Leary

Very interesting, I had not heard much about naval battles in World War I, but, knew that Great Britain had been a naval power after beating the Spanish Armada and well into World War II. I found it interesting how the German emperor wanted a larger navy ever since watching the ships in his grandmother’s house in England, and his fleet ends up fighting against the English navy.

Danielle Slaughter

Interesting article. I always appreciate when someone calls attention to World War One, rather than the oft-referenced World War Two. It comes as no surprise to me that the Germans were set to outpace the British when it came to naval power, as their industrialization had reached a peak only within the previous few decades. Overall, this was well-written, though I have to add something: At the end of the article, you mentioned that British sea power was not compromised, and that all battleships were intact, when in a the paragraph before you mentioned three that were destroyed.

Christopher Hohman

Hi Danielle. Thanks for reading my article. I always appreciate when people do because mine tend to be pretty long. I love talking about naval battles in WWI because they are often less known then those in the Pacific or Atlantic during WWII. Also, British sea power is something of an obsession of mine. There are differences between battleships and battlecruisers. Battlecruisers were slightly smaller, with less powerful weapons, but were much faster than battleships. Battleships and Battlecruisers were two distinct classes of ship at Jutland.

Danielle Slaughter

Ohh, okay! Thanks for the clarification. I did know the difference between battlecruisers and battleships.

Joshua Garza

This is a really good article. I’ve always been interested by World war one because it is the first modern war we have with technology and ideas of technology that are still used today in 2019. The soccer game that was held on Christmas day is my favorite moment by far because its something that probably will never happen again.

Mariah Garcia

This was a really fun article, easy to read, and the subject matter was definitely not one that I was familiar with. The Battle of Jutland was something that I do not recall learning about in any of my grade school history classes, and it was good to read the details of such an integral battle in such a raw retelling.