In the eleventh century, the Iberic peninsula was filled with feudal kingdoms. Spain and Portugal did not exist as a country, and the most notable difference between that time and today was the Islamic occupation of the southern part of the peninsula. This occupation by the Islamic people started in the eighth century and continued right up to the time of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand in the sixteenth century. The small Catholic kingdoms of the north united against the Islamic forces in the last four hundred years of that period, which came to be called “La Reconquista.” La Reconquista was able to reclaim, little by little, the Islamic empire of the peninsula. During this period, there was one person who stood higher than even some kings. He was Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar “El Cid.” Rodrigo passed to history as a legend and a symbol of pride for Spain. El Cid would taste glory multiple times throughout his life, but there are some low moments in his story too, like his years in exile from Castile.1

King Alfonso VI, King of Castile, tried to unify the northern kingdoms of Spain to fight against the Islamic Taifa of the south. Alfonso named himself emperor of all of Spain in 1077 CE and had Rodrigo as an ally. In 1081, Alfonso was preparing an army to attack Muslim lands, and Rodrigo stayed behind, saying he was sick. However, he would shortly after respond to a Muslim attack on the fortress of Gormaz, which was a fortress that Rodrigo oversaw. To avenge the attack, Rodrigo invaded, looted, and devastated Muslim lands from Toledo’s Taifa. Even if Rodrigo had valid reasons to attack Muslim lands, Alfonso was not happy about it. Alfonso lived in Toledo during part of his life and was an ally of the Taifa. Rodrigo’s reckless attack led to a breach of trust from the Taifa against Alfonso VI, and it interfered with his plans to take the Andaluz regions. As a punishment for his insubordination, Rodrigo was sent into exile. It is possible that Alfonso used Rodrigo’s unauthorized campaign as a mere excuse to get rid of El Cid, fearing his growing influence in the court and following the influence of other nobles who were jealous of Rodrigo. El Cid’s exile brought shame to his name. Nevertheless, his later exploits would erase that humiliation.2

By sending Rodrigo away, Alfonso kept peace with Toledo and made the whole event seem like the rant of an insubordinate subject. This later proved to be beneficial for both. Alfonso kept his alliance, and El Cid would become a legend. El Cid was left with just some relatives, friends, and a quad of Christian knights, which was not very numerous. However, his army started getting bigger as both Christian and Muslim knights joined him in his exile. Rodrigo traveled to the court of Barcelona to offer his services to the twins Ramon Berenguer II and Berenguer Ramon II. However, the twins rejected him. Rodrigo then went to the Taifa of Zaragoza, where the veteran king Al-Muqtadir welcomed him. During that period, Zaragoza was one of the most important Taifas of the peninsula. Being a city of great cultural and scientific importance, Al-Muqtadir saw El Cid as a great military ally. Rodrigo created a disciplined army out of his mix of Christian and Muslim warriors, to defend Zaragoza from external threats. However, Al-Muqtadir would not live long enough to see the glory that El Cid brought to Zaragoza.3

In 1081, Al-Muqtadir died months after Rodrigo became the leader of his army. The monarch divided his kingdom between his two sons: his oldest son, Al-Mutamin, got Zaragoza, and the youngest, Al-Mundir, got Lerida, Tortosa, and Denia. Soon after the death of Al-Muqtadir, his sons went to war against each other for control of the whole Taifa. Al-Mundir found allies in Berenguer Ramon II, “The Fraticide,” one of the twins from Barcelona, and the king of Aragon, Sancho Ramirez, all three Christians. Meanwhile, Al Mutamin asked Rodrigo for his assistance, and El Cid would show once again why he was also called Campeador (Master of battles). Rodrigo gathered a hybrid army with a base of his Christian knights and the Muslim troops of Zaragoza. El Cid defeated the troops of Lerida and Barcelona in Almenar around the spring or summer of 1082. When the coalition between Ramon Berenguer II and Al-Munir attacked Almenar, which was part of the Taifa of Zaragoza, El Cid moved his army to protect the city. El Cid defeated the troops of Ramon Berenguer II and even captured him, although El Cid let him go eventually. This battle consolidated the power of Zaragoza in the region and stopped the Christian expansion in the Taifa, and for Rodrigo, it contributed to his status as a legend.4 El Campeador also faced the forces of Lerida and Aragon in Morella years later, in 1084. It was also known as the Battle of Olocau. El Cid took the castle in Pobleta de Alcolea, to harass the important city of Morella, which was under the control of the Taifa of Lérida. Soon both armies clashed near the city. Rodrigo, being a skilled general, led his troops and emerged victorious. This battle is considered a crucial moment in El Cid’s career and a testament to his military prowess. It showcased his ability to lead his troops to victory against a formidable coalition, even while serving a Muslim ruler. Rodrigo became a sort of minister in military issues, and General of the Taifa of Zaragoza.5

In 1085, while El Cid took care of Zaragoza’s safety, Alfonso VI conquered Toledo. This conquest was of great importance during the Reconquista. Toledo had been the capital of the Visigothic kingdom that had existed from before the Islamic invasion in 711. The fall of Toledo shifted the balance of power in the Iberian Peninsula, strengthening the position of Christian kingdoms and weakening Muslim rule. Alfonso was on his way to free Spain from the Islamic influence, but the so-called “Imperator of all Hispania” did not get to celebrate for too long the success of his political and military achievement. A dangerous threat for the Christian kingdoms began to emerge in the south: The Almoravids. These Berber warriors arrived at the peninsula, called by some Taifa kings, to protect the Al-Andaluz (Muslim part of Spain). These warriors followed the Islamic law with great rigor; they aimed to purify the Al-Andaluz and to stop the influence of the Christian kingdoms. Having already a strong empire in the north of Africa, the Almoravids, led by Yusuf ibn Tasufin, allied themselves with other Taifa kingdoms. With that powerful army, Yusuf led his troops towards Badajoz.6

The year 1086 was to be remembered as the year of one of the most awful defeats for Alfonso VI. Near Badajoz, the battle of Sagrajas took place. This battle was one of the most humiliating moments for Alfonso and his army, and a hard setback for the Reconquista. The Almoravids used cavalry to destroy Alfonso’s forces and took the city. The monarch managed to escape from the Islamic forces. During this time, El Cid was still fighting for Zaragoza and not involved with the problems of his king. Alfonso knew he needed his best warriors to defend Spain. In December 1086, Rodrigo was forgiven by Alfonso VI after nearly five years of exile. This decision can be attributed to the fact that El Cid had a deep understanding of Islamic societies after spending several years in a Taifa. Alfonso sent Rodrigo to the city of Valencia to protect the Taifa king Al-Qadir who in 1085 was the one who gave up Toledo in exchange for Valencia’s throne. During 1087-1088, El Cid was a good vassal for his king, and he took charge of creating a good army of both Christians and Muslims and creating a military and fiscal system by sending incursions into small kingdoms that did not pay tribute to Alfonso.7

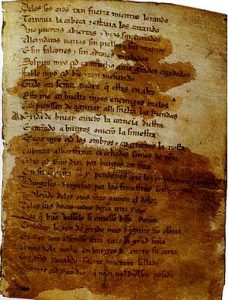

El Cid proved himself useful to Alfonso during those years, but he had many more challenges in his life. His first exile is a testimony of El Cid’s resilience, military genius, strategic mind, and strong leadership. El Campeador eventually conquered the city of Valencia without serving any monarch, becoming one of the greatest warrior minds of his time. Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar became a legend for the people of Spain, a patriotic figure. El Cid’s journey, marked by both triumphs and trials, is a testament to his exceptional character and military prowess. His exile, a consequence of political intrigue and personal ambition, served as a catalyst for his rise to legendary status. The challenges he faced only strengthened his resolve and sharpened his skills. His future exploits, particularly the conquest of Valencia, solidified his reputation as one of history’s greatest warriors and leaders. El Cid’s legacy would inspire generations, forever etching his name in the annals of Spanish history. El Cid’s story can be found in medieval texts written during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the most important and where his legendary status comes from is “El cantar del mio Cid.” (“The Song of My Cid”).8

- Charlene E. Suscavage, “El Cid (Spanish Military Leader),” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- Giorgio Perissinotto, “Jack Weiner. El Poema de Mio Cid: El patriarca Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar trasmite sus genes,” Symposium 56, no. 4 (January 1, 2003): 235. ↵

- “El Cid,” New World Encyclopedia, accessed November 9, 2024, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/El_Cid#Exile. ↵

- Charlene E. Suscavage, “El Cid (Spanish Military Leader),” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- Giorgio Perissinotto, “Jack Weiner. El Poema de Mio Cid: El patriarca Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar trasmite sus genes,” Symposium 56, no. 4 (January 1, 2003): 235. ↵

- Oscar Martin, Rodrigo Díaz, Del Hombre Al Mito: Textos Y Contextos De La Primera Tradición Cidiana (1099-1207), Edwin Mellen Pr, 2015. ↵

- Oscar Martin, Rodrigo Díaz, Del Hombre Al Mito: Textos Y Contextos De La Primera Tradición Cidiana (1099-1207), Edwin Mellen Pr, 2015. ↵

- Raquel Crespo-Villa, “Tres modelos para la reconstrucción posmoderna del héroe medieval: La figura de Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar en tres novelas históricas españolas del siglo XXI,” 2015, https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/671665. ↵

6 comments

arosales11

This reading effectively brings El Cid’s narrative to life. It’s incredible how he went from being banished and losing everything to being one of the most recognizable individuals in Spanish history. Even when odds were stacked against him, he persisted and found methods to succeed. I believe it’s extremely incredible that he was able to lead both Christian and Muslim troops , it demonstrates how excellent he was at bringing people together, especially during such a divided period.

Macarena Machado Combe

I found it fascinating how El Cid managed to join both Christian and Muslim knights under his command. This highlights his leadership and the respect he commanded across different cultures and religions during such a turbulent period. The union between to really different groups happened due to the remarkable character and presence of one person, demonstrating that with determination and motivation, significant achievements are possible. Overall, this article was informative and offer a good summary of El Cid role on medieval politics.

Danielle Villanueva

This article provides a fascinating look into the life of El Cid during the complex period of the Reconquista. I was impressed by how Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar navigated the political landscape, working with both Christian and Muslim rulers. His ability to build a diverse army and survive exile shows remarkable leadership. I’m curious about how much of his story is historical fact versus legendary embellishment, especially given the mention of the epic poem “El Cantar del Mio Cid.”

Cesia Gonzalez

You really bring his story to life with all the details and the drama. The way you describe his journey and struggles is super engaging. It’s clear you’ve put a lot of thought and work into it. Great job on making history so interesting and accessible!

Alysia Cano

El Cid’s story is a remarkable blend of resilience, strategic brilliance, and legendary heroism. His ability to navigate alliances across cultural and religious divides, coupled with his military genius solidified his place as a symbol of Spanish pride. The challenges he faced, particularly during his exile, only highlight the strength of his character and the enduring legacy he left for future generations.

ncuarenta

This reading really brings El Cid’s story to life. It’s amazing how he went from being exiled and losing everything to becoming one of the most famous figures in Spanish history. Even when things were against him, he kept fighting and found ways to succeed. I think it’s really impressive how he was able to lead both Christian and Muslim troops—it shows how good he was at bringing people together, even in such a divided time.