The year is 1932. The place, Berlin, Germany. The date, November 6. On this day, the fourth and final election of the year took place for seats in the Reichstag, which was the legislative body of the Weimar Republic. All the major political parties in Germany were vying for seats in the legislature. Although this was the fourth election of the year, it was arguably the most important, and even more important than the recent presidential election had been. The Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), or the National Socialist German Workers Party in English, otherwise known as the Nazi Party, had been controlling seats in the Reichstag since the July election. Led by Adolf Hitler, the NSDAP had become one of the most popular parties in the Weimar Republic up to that November election. The seats in the Reichstag would be filled by five main political parties in Germany: The NSDAP, Deutschnationale Volkspartei (DNVP), or German National People’s Party, Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD), otherwise known as the Communist Party of Germany in English, Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschland (SPD), or Social Democratic Party in English, and the Zentrumspartei, otherwise known as the Catholic Centre Party.1

In this November election, the NSDAP lost 34 seats compared to its July election results, while the DNVP and the KPD gained seats back. This was pivotal for the future of Germany, and especially for the President Paul von Hindenburg. Being a conservative independent, he found it ever increasingly difficult to lead the Weimar Republic. Hindenburg had become very worried about the rise of the NSDAP. He was concerned mainly with their leader, Adolf Hitler, who showed signs of extremist ideologies. After the July Reichstag elections, the Nazis had become the largest party in the Reichstag. It was assumed that the leader of Germany’s largest party, Adolf Hitler, would be appointed Chancellor of the Republic. But Hindenburg distrusted and disliked Hitler and refused to appoint him. Thus, this November election reassured Hindenburg and the rest of the Weimar Republic, that the Nazi Party had peaked and was now on the decline. Even the Nazi party leadership thought so. But the current Chancellor, Franz von Papen, found it almost impossible to govern. He could form no coalition government in the Reichstag, and had lost the confidence of his cabinet.2

At this time in 1932, Germany was in the depths of the Depression. By the end of November, the economic depression was at its all-time worst. Unemployment was in the 30% range. President Hindenburg was having trouble controlling the economic nosedive and its accompanying political chaos. So, despite the results of the recent election, the Nazis road a wave of popularity. Hitler used the hardships of the depression as a way to appeal to the middle and lower-middle classes. He employed propaganda to take advantage of the vulnerability of these German citizens. Many had lost faith in democracy and were open to more extreme parties, especially the NSDAP and the KPD. Nevertheless, by the end of November, the Nazis had peaked, and yet the Depression raged on, and the German government was adrift.3

On December 1, President Hindenburg met with the former Chancellor of the Weimar Republic, Franz von Papen, and the Minister of Defense, Kurt von Schleicher. Hindenburg had exhausted all options in trying to curb unemployment and was open to any and all ideas that would reduce the effects of the Depression. Franz von Papen had been Chancellor before the November elections, and Hindenburg had to appoint someone now to try to form a new government. He wanted to reappoint Papen, but Papen was unable to form a coalition government in the Reichstag, which meant that he would have to rule, not through normal parliamentary governing through the Reichstag, but through Hindenburg’s presidential emergency decrees according to Article 48 of the Weimar constitution. This would be called a “Presidential Cabinet,” which would be a legal option for governing, but not the most desirable. Papen then suggested at this meeting that Hindenburg reappoint him as Chancellor and his former cabinet. The Reichstag would certainly not support him or his cabinet, and he would then have to suspend the Reichstag for a while, which would be unconstitutional, but necessary. In effect, he suggested a revolution. He suggested a whole new style of government: an authoritarian government where there would be no political parties and no trade unions. This type of government would be backed by military and police rule, “for a short time.” In other words, he was proposing the overthrow of the Weimar Republic in favor of a military dictatorship, in the guise of dealing with a state of emergency. The one thing holding Papen back from following through with his plan was that he would need the help of the Reichswehr (the German military) to back him up in these efforts. To do this, he would need the cooperation of Kurt von Schleicher who, as the recently appointed Minister of Defense, was in charge of the Reichswehr. But Schleicher didn’t believe that Papen’s plans would work. He flatly stated that the Reichswehr was simply not up to job. And it could not be relied on to take action against the Nazi paramilitary forces, or the SA Brownshirts. This matter was important to Schleicher because he could not bear to see a political civil war take place in which the Reichswehr would be pitted against both the Nazis and the Communists. To Schleicher, the only real salvation for the Republic would come if he himself were to be appointed chancellor. Hindenburg decided to give Papen a chance, and reappointed him Chancellor. When Hindenburg left the meeting, Papen and Schleicher engaged in extremely heated exchanges.4

The next day, on December 2, President Hindenburg’s cabinet reconvened. They picked right back up where they left off the previous day. Schleicher told Chancellor Papen once more that if he tried to form the authoritarian-style government he wanted, it would cause extreme political divide and bring the country into chaos. He also said that the Reichswehr would not support action against the Nazi SA. Hindenburg, the war hero of World War I, felt betrayed at hearing that his army would rather support Hitler than himself. But nevertheless, he saw no other way than to follow Schleicher’s way of thinking. Ultimately, Hindenburg made the difficult decision to withdraw Papen as chancellor. Later that day, President Hindenburg appointed Kurt von Schleicher to be the next chancellor of the Weimar Republic.5

One may ask, what gave Hindenburg the right to appoint the chancellor of the Weimar Republic? How did he have this power? After World War I, when the Weimar Republic was established, the main goal of the political parties in charge was to rule as a democracy. They created a constitution to clearly define laws that would govern their democracy. During this process, the designers of the Weimar constitution wanted to implement a system of checks and balances that would reduce the possibility of a rebellion or coup. Six articles were created with this end in mind.6 The articles that were used the most for that purpose were Articles 48 and 53. Article 48 allowed the President to rule by emergency decree when emergencies arose. President Hindenburg enacted this article on numerous occasions.7 It was one of the only ways to get laws passed if the Reichstag became dysfunctional, as it was for most of 1932. Article 53 allowed for the president to appoint and dismiss the chancellor. This law, too, gives the president complete authority over the Reichstag, undermining the democratic process. This is how President Hindenburg was able to appoint first Papen, and then Schleicher, and eventually also Hitler, to the position of chancellor. Articles 48 and 53 is what ultimately led the Weimar Republic to become more of an authoritative government during the final years of its existence.8

Kurt von Schleicher, as the new chancellor of the Weimar Republic, did not waste any time in trying to get things done. He immediately went to destroy the Nazis. His first way of doing this was to meet with Nazi leader Gregor Strasser. During this meeting, Schleicher offered Strasser the Vice-Chancellorship in hopes of making Hitler envious, attempting to pit the Nazi leaders against each other. Trying to play both sides for his own personal gain, former Chancellor Papen informed Hitler about the meeting between Schleicher and Strasser. Hitler then called a meeting with Strasser where he confronted him about his meeting with Schleicher. Strasser told Hitler that he supported Schleicher. The two got into a shouting match. Strasser accused Hitler of ruining the Nazi Party. Hitler accused Strasser of stabbing him in the back. On December 8, Strasser resigned from his position in the Nazi Party, leaving Hitler and the rest of the Nazi Party stunned. Gregor Strasser had been a founding member of the party. The Nazi party began to unravel, and Hitler went into a deep state of depression.9

During this time, Schleicher was trying to push new laws through the Reichstag; however, this did not end in his favor, as none of his proposals were passed. The fact that the Reichstag had become again dysfunctional worried the Nazis. They feared that Schleicher would dismiss the Reichstag and call for new elections, to elect members that were more sympathetic to his agenda. The Nazis knew that new elections would destroy them because they had lost all their momentum.10

In January of the next year, Chancellor Schleicher had a change of heart. He began to support Papen’s earlier plan of an authoritarian government. After Papen was relieved of his chancellorship duties, he remained close with President Hindenburg. Because of this, Hindenburg still took his advice very seriously. Papen was still trying to convince the President that an authoritarian government would be beneficial, but Hindenburg did not give in. Not getting the support he sought from President Hindenburg, Papen turned to Hitler. He hoped that an authoritarian government could be achieved if Hitler was in power. He believed he could manipulate Hitler into doing things that would benefit his own personal gain. Papen began to meet with Hitler to start discussing possible government arrangements, should Hitler be appointed Chancellor.11

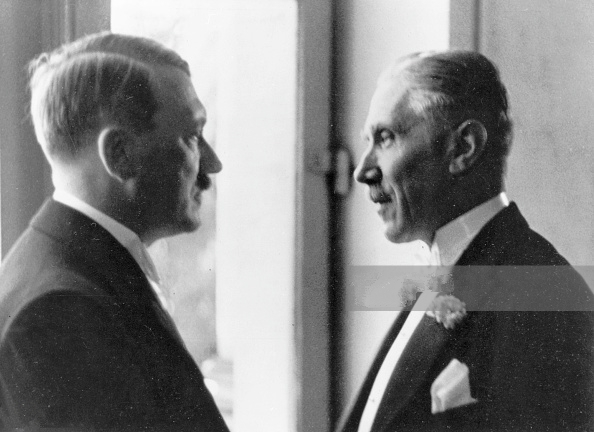

On January 22, 1933, there was a secret meeting in the home of Jochim von Ribbentrop, a Nazi diplomat. The meeting consisted of Hitler, Papen, Oskar von Hindenburg (son of President Paul von Hindenburg), and Hermann Goering (another figure in the Nazi party). Hitler talked to Oskar von Hindenburg about the potential of himself being appointed Chancellor of the Weimar Republic. It was during this meeting that Papen openly pledged his loyalty to Hitler.12

While this is all happening, Schleicher went to Hindenburg and asked him to declare a state of emergency against the Nazis. Schleicher wanted to suspend elections and dissolve the Reichstag. He was trying to do anything he could to stop the Nazis’ late surge of momentum. But Hindenburg denied Schleicher’s request. Everyone started to lose faith in Schleicher as the Chancellor. No one would trust him. He contradicted everything he said and every action he tried to make. The date was January 28, 1933. Schleicher again went to Hindenburg, pleading with him to dissolve the Reichstag and let him rule by emergency decree without calling for new elections. Hindenburg was faced with a difficult choice. He could either support Schleicher’s idea of military rule, which was illegal and unconstitutional, or he could go the legal route and appoint a new chancellor. Hindenburg, however, didn’t want to be known as the President who destroyed the Weimar Republic, so he denied Schleicher’s request again. Soon after the meeting, Schleicher resigned his position as Chancellor of the Weimar Republic. Now that Schleicher was out of office, Papen whispered in Hindenburg’s ear who he thought should be the next chancellor. The name that Papen kept pushing for was Adolf Hitler.13

Adolf Hitler was born in a town in Austria called Braunau am Inn in 1889. He was born to a lower-middle class household. Hitler’s childhood was very uneventful. In 1913, Hitler fled to Munich in hopes of escaping service in the Austrian army. A year later, he coincidentally volunteered for the German army in World War I. While in the army, he was recognized several times for his bravery among other things. Once back in Munich working after the war, he came into contact with a few members of the German Workers Party, which would soon be known as the Nazi Party.14 Hitler made his name known in the party throughout the years. His radical ideology made him appeal to a much broader audience rather than a specific group of people. By 1930, he had support from the Protestants, mainly from rural regions and small towns, and from people who grew up in middle-class households. He also attracted the support from women young and old, because they had more opportunities with the Nazi party than with the KPD. Hitler did not really appeal to the working class, to the unemployed, to those in large urban centers like Berlin, or to Catholics. In each group, there were a few people that did support the party, but it was very underrepresented in the votes.15 Hitler became the face of the NSDAP, and his popularity grew to an all time high in July of 1932. Part of this was him getting people to believe in the Nazi ideology.16 The other part was that Germany was in complete economic and political turmoil, and the Nazi party was the party that seemed to show a dynamism lacking in the other parties. But still, one may ask, Why Hitler? Hitler had no political experience and had no previous education. Papen thought that this was perfect for him. He believed, if he could get Hitler to become Chancellor, he would still be able to control him and manipulate him. In Papen’s words, “he would be a Chancellor in chains.” Papen couldn’t have been more wrong.

On January 30, 1933, Hindenburg called Adolf Hitler for a meeting. Hindenburg then appointed Hitler as the new Chancellor of Germany. From this moment on, the course of history would never be the same. Hitler’s rise to power was an unusual one that started with him being a nobody from Austria, but it led to him becoming one of the most feared and notorious figures in world history.17

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 371, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 372-373, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

- Ruth Henig, The Weimar Republic 1919-1933 (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 1998), 72-73. ↵

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 389-393, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 394-397, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

- Anthony McElligott, Rethinking the Weimar Republic: Authority and Authoritarianism, 1916-1936 (A&C Black, 2013): 183. The articles were 25, 35ii, 41i, 48ii, 53, and 54. ↵

- Marc de Wilde, “The State of Emergency in the Weimer Republic Legal Disputes over Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution,” Tijdschrift Voor Rechtsgeschiedenis/Legal History Review 78, no. 1 and 2 (January 1, 2010): 137-140. ↵

- John P. McCormick, “The Crisis of Constitutional-Social Democracy in the Weimar Republic,” European Journal of Political Theory 1, no. 1 (July 1, 2002): 126–128, https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885102001001009. ↵

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 399-400, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 401-409, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 410-416, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 421-424, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

- Sidney B. Fay, “Hitler—Chancellor of Germany,” Current History (1916-1940) 37, no. 6 (1933): 742. ↵

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler (London, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group, 2000), 1-2. ↵

- Brian Ault and William Brustein, “Joining the Nazi Party: Explaining the Political Geography of NSDAP Membership, 1925-1933,” American Behavioral Scientist 41, no. 9 (June 1, 1998): 1304-1308, 1319-1320, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764298041009008. ↵

- Barbara Miller Lane and Leila J. Rupp, Nazi Ideology Before 1933: A Documentation (Manchester University Press, 1978), x-xxiii. ↵

- Andreas Dorpalen, Hindenberg and the Weimar Republic (Princeton University Press, 1964), 440-446, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pm5s. ↵

32 comments

Carlos Alonzo

I think that everyone knows or is at least familiar with Adolf Hitler. The fall of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Hitler in Germany were significant chapters in history. Obviously, the story of Hitler shows the dangers of extreme political ideologies. This not only cost the lives of many people but caused subsequently economic turmoil, political instability, and allowed someone not fit for power rise to power. This is an important reminded of protecting democracy and to prevent the repetition of such a tragic event.

Joseph Frausto

Congratulations on your nomination and success! Let me just say that that is a really eye catching picture that draws a reader in to an amazing article. Analyzing the political conditions that let figures such as Hitler rise is so important for us to study and learn from. Great job.

Illeana Molina

This was a fantastic read! This a great article. Congrats on the well-deserved nomination. This article is accompanied by a great image, a title with a good hook, and well detailed on Hitler and how he was as well as how he gained power. We do see and have learned to be touched on the Nazi regime/party. As Aaron stated, “the Weimar Republic of Germany dissent into the grasp of the party ran under Adolf Hitler. ” we all need to be informed, educated, and well-rounded when it comes to historical information on what occurred in Germany.

Aaron Astudillo

Congratulations on the nomination for the article. This is a very well-written article about the Weimar Republic of Germany dissent into the grasp of the party ran under Adolf Hitler. It is important for all to be informed about this topic, especially considering the democratic nature of Germany’s history, into the fall of authoritarianism.

Maximillian Morise

A great article detailing in depth the Weimar Republic of Germany’s dissent into the grips of authoritarianism and fascism in the hands of the National Socialist Party under Adolf Hitler. People often forget that Adolf Hitler took power through election, rather than seizing control for himself. It is a warning of what democracy can become if we are not vigilant of those attempting to usurp it. Congratulations on your nomination!

Peter Alva

Congratulations on the Nomination! I enjoyed reading this article for a few reasons. The main reason is for how detailed this article is, it kept me intrigued and had some sort of suspense to it. Before this, I definitely thought that he had it a lot easier but reading this I can see that doing this was hard but the following is what made his vision possible.

Iris Reyna

Congrats on your article nomination Ryan, good job on the article it was a fascinating article to read. I really liked the format of your article, it was organized amazingly. You did a good job at bringing me into your article. Everyone learned about Adolf Hitler and the war during school but reading your article was entertaining and made me want to relearn the history of the war that consisted of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. It was a good read and very informative.

Melyna Martinez

Hello, this article gives a great perspective in Hitler and how he rose to have the power to impact the world forever. The political instability in Germany after World War I led to the chaos of the parties that influenced Hitler to lead one. It is so interesting to see that every small step Hitler took to have the power he wanted lead him to kill millions through the holocaust.

Alexia Gutierrez

I think the most interesting piece of information that I learned from reading this article is that Hitler’s rise began with Papen thinking he could control Hitler once he became chancellor. I could not imagine how one can feel after making such a huge mistake and then watching all plans to crumble. Can we imagine how things would have played out if it wasn’t for Papen.

Abbey Stiffler

Congratulations on being nominated. The author did a fantastic job of describing this fascinating story. To imagine that someone gaining control of a nation would alter history significantly and affect many people’s lives is crazy for how long he was in power. The specifics of the talks between Hitler and the previous leaders that resulted in his ascent to power in Germany in the 1930s are quite intriguing to learn about.