Benedict Arnold, former general in the Continental Army, was staring at the retreating shore of the Hudson while taking passage on the HMS Vulture. He knew he could never step foot on his homeland again without the risk of being hanged, but he knew these risks before he committed treason. Arnold retreated to the quarters of the Vulture to write a letter to his former commander and once friend, George Washington, to at least let his wife Peggy get safe passage to her family in Philadelphia.1 Now Arnold traveled to England to fully commit to a cause he once fought so valiantly against.

To understand what caused Arnold to commit his act of treason, let’s travel back to October 17, 1777 during the Battle of Saratoga. Let’s return specifically to the second assault just three years prior to his treason. General Horatio Gates, the commanding officer of the army for both Battles of Saratoga, did not get along well with Arnold ever since Arnold’s rise to power in the ranks due to his “aggressive tactics.” Gates gave an order telling Arnold that he no longer had field command, due to their latest argument.2 When the second battle took place, Arnold noticed that one of the enemy’s lines was weak, so he rallied his troops, against Gates orders, and charged the line, breaking through easily. While charging, his horse was killed, but he got back up and continued the charge until he was shot in his left leg, almost crippling him.3

Arnold didn’t return to duty again until May 1778, even though his leg was still healing. A month later, Arnold was made military commander of Philadelphia by George Washington as an token of his appreciation.4 Even though Arnold had no real qualifications to run a city, Washington needed to give Arnold something in order to appease him. The reason why he had to appease him wasn’t only because of his contribution to Saratoga, but also because of other promotions and successes that Congress was not giving Arnold credit for. The reason why Congress did this was because most members of Congress, including the future Anti-Federalist Richard Henry Lee, blamed Arnold for the loss of the navy in Quebec.5 They didn’t trust Arnold since that point, even though other generals, including George Washington and Horatio Gates, said it wasn’t Arnold’s fault and that Arnold did the best he could do with the hand he was dealt.

The first time Congress overlooked his contributions was at the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, which they believed Ethan Allen and his men were to get credit, until Washington himself gave credit to Arnold.6 The second time Congress insulted Arnold was in refusing to promote him to Major General. Congress wanted to keep the number of generals from each state even, and so they would pick generals based on that ratio rather than on the basis of one’s proven skill, which angered Arnold and made him want to resign as a general; but Washington stepped in to calm Arnold down.7 The final disrespect by Congress to Arnold was his promotion to Major General with seniority, which meant that if there were two Major Generals on the same battlefield, Arnold’s orders would override the other Major General’s orders, giving Arnold command of the Army. You would think this is what Arnold would want, but to Arnold, it seemed that Congress only gave him the promotion due to his injury rather than for his military success. Arnold believed that they should have apologized for overlooking him for the original promotion, but Congress never did.

Arnold arrive in Philadelphia, one of the richest cities in the colonies, to take up his command. Arnold wasted little time after his arrival to take advantage of the good life of this fine city. Arnold proceeded to do many things to deepen his pockets and increase his status while in charge of Philadelphia. First, Arnold commissioned American privateers, or specifically the crew from the ship Charming Nancy, to bring a variety of goods to Philadelphia so that he could sell them to make a side profit on the needs of Philadelphia. Because the Charming Nancy couldn’t make port in Philadelphia, but rather had to go to a New Jersey port to land safely, due to nonaligned pirates trying to steal his cargo. Arnold secured available army wagons to bring the goods back from New Jersey to Philadelphia. He planned to sell the cargo of fine glass, sugar, tea, bolts of woolen cloth and linen, nails, rope, and swivel guns for a personal profit.8 Arnold used his title of military commander to make this happen, even though it was not military business. Arnold then moved into the Philadelpia mansion that British General Howe had been occupying when the British had controlled Philadelphia, and he would also ride around town in a expensive carriage he bought just to show his importance to all of Philadelphia’s wealthy citizens.9 These activities weren’t illegal by any mean, but they were things he probably shouldn’t have been doing while commander of the city. As you can tell, Arnold wasn’t that well liked soon after he arrived, and he didn’t help his case any further by going to lavish parties just to scout the field for potential brides, which he eventually was successful at, when he found his future wife, Peggy Shippen.

However, Arnold’s questionable behavior finally caught up to him when Joseph Reed, the head of Philadelphia’s city council, along with the council’s secretary Joseph Matlack, confronted Arnold on his “illegal” business dealings. They also questioned why Arnold, as military commander, had Matlack’s son, who was serving in the state militia, fetch Arnold a barber, which was a task well below his son’s pedigree. Arnold said he had done nothing wrong, and said that, as a soldier, he had the freedom to do as he pleased and that it was his freedom to do so.10 Matlack said he would pull his son out of the militia and blast Arnold in the newspapers. Arnold replied in a letter saying that civilians shouldn’t be sticking their noses in military matters, and he could care less what Matlack put in the papers. The council, in response, charged Arnold with a number of crimes and sent copies of his charges to Congress, to George Washington, to all state leaders, and to all regional newspapers.11 They also wanted Arnold fired as the military commander of Philadelphia, so they requested a court martial of Arnold.

Arnold asked Washington what he should do to clear the air in Philadelphia. Washington recommended that Arnold go through with the court martial to prove that he was innocent of all charges. Seeing no other way of avoiding tarnishing his reputation further, Arnold agreed with Washington. Arnold was charged with eight charges, each with varying severity, but most being vague and not having a lot of evidence to prove that he had done anything wrong. The first charge was that he allowed a schooner or a small ship to pass without the council’s approval. The second charge was his closing all the stores in Philadelphia, though he had permission to do so by General Washington.12 The third charge was his demeaning treatment of the secretary’s son, and the fourth charge was his hazy dealings and his business practices. The fifth charge was his use of the army wagons for his personal use, even though he used them when they weren’t being used by the military and it didn’t conflict with schedules; plus he paid for their use out of his own pocket. The sixth charge was that he overruled a matter that the council agreed to by allowing someone to enter enemy lines. The seventh charge was over his refusal to explain to the council why he needed the wagons; and the final charge was an attack on his character.13 Out of the eight charges, only four could be used in a court martial, and out of those four, only two could be proven.

Arnold petitioned for the court martial to begin right away, since that was his best chance, and anyway, he resigned as commander of Philadelphia two days later. The original date of Arnold’s trial was May 1, giving the city council less than two weeks to find evidence. So the city council asked Washington to give them more time, and he obliged. Then he gave them more time due to Congress telling Washington to help the city council as much as possible, so he gave them until July 1.14 Arnold was beyond livid. Not only was Congress helping the city council with its case against him, but they were making Washington, his only ally left, to help the Philadelphia city council as well. Arnold was starting to question why he had sacrificed his body for the revolution in the first place, if they were going to treat him like this.

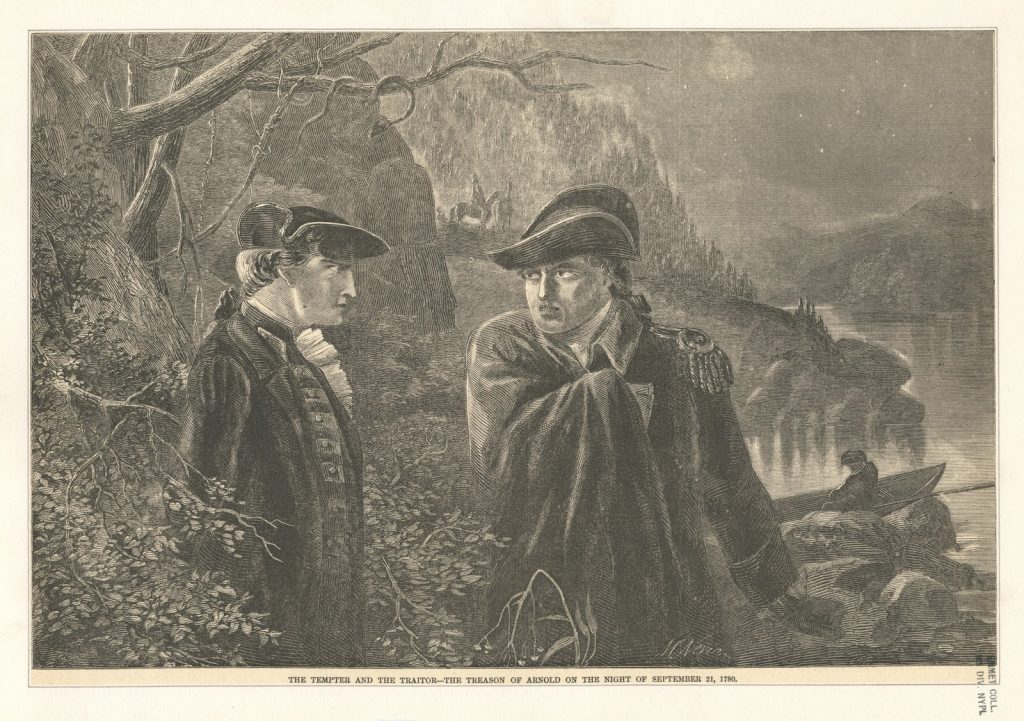

That’s when an opportunity arose for Arnold; however, this time it wasn’t with the Americans but rather from the very Empire that gave him his limp. Arnold was already thinking about changing sides beforehand, due to his wife Peggy, who was a loyalist, giving him some suggestions to defect. Arnold met a man named Joseph Stansbury, who was a loyalist merchant, who had ties with the British military. Arnold said that he was interested in changing sides to Stansbury. That’s when Stansbury stepped in and introduced Arnold to the British spy chief, John Andre.15 Arnold chose to hear out the British proposals.

Arnold told Stansbury that he would help the British defeat Congress and help them restore British rule to the colonies only if they planned to finish the war. The reason Arnold worded his terms this way was because he wanted to make sure that if he joined them, it would be to make sure he didn’t change sides for a war that was going to end unfavorably for him.16 These were Arnold’s only conditions for helping the British, besides a fair compensation and a position in the British military. Andre accepted Arnold’s initial proposal, and forwarded it to Sir Henry Clinton, one of the British generals of the area, who subsequently accepted the deal. Arnold then became greedy, and tried to get even better terms while feeding some information to Clinton to show that they could trust him. Arnold, however, was hoping that Congress would better recognize him, that Pennsylvania would drop all their charges against him, and that he would finally get a field command once again and fight for America. Arnold was ready to pull out of his negotiations with the British if any of these conditions happened, and he would just play off the deal-making by saying he was tricking the British; but that day came far too late.17

The final offer that Arnold was offered was £20,000 in British currency in return for his army’s surrender at West Point, which was a fort that Arnold had just been given by Washington as a “no hard feelings” gesture after his court martial. He was also to hand over supplies and artillery equipment, including at least 3,000 men.18 Arnold had to complete these requirements in order to get paid in full by Clinton. Arnold went straight to work by lying to Washington, saying that he needed more men and supplies. While doing this, he supplied Clinton with the layout of West Point to give him the most efficient way to capture the fort. All that needed to be done was for Andre to arrive back to HMS Vulture to deliver the plans, and the plot would go without a hitch. However, the capture of West Point never happened.

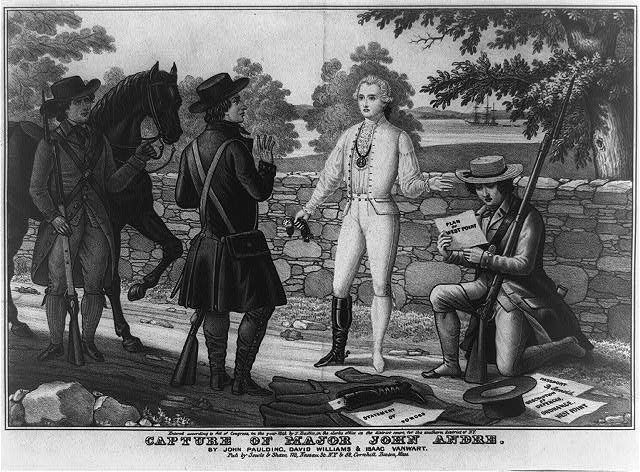

John Andre was making his way to the rendezvous with the HMS Vulture, but he had been delayed due to minor damage to his ship. So instead, Andre had to go by land to deliver his package. But by a twist of fate, Andre was captured by bandits.19 The bandits were actually just intending to rob Andre and take his things, until they noticed the papers he was carrying. They turned Andre into the nearby headquarters of Washington, who had just happened to be visiting Arnold that day.20 The command quickly sent Washington a letter telling him that Arnold was a traitor. But the letter that outed Arnold as a traitor and was meant to go to Washington’s hands at West Point went first to Arnold’s hands, since he was in charge of West Point. Arnold read the letter to himself, since he thought it was to him. Once he discovered that he had been made, Arnold quickly fled to the HMS Vulture for refuge.

Once Washington found out about the plot, he quickly tried to make a deal with Clinton to give Andre back to them if they just handed Arnold over. Clinton refused and Andre was hanged for treason, since he was acting as an spy for Britain.21 Arnold was subsequently granted the rank of British general, and the pay of one as well; but he wasn’t given the £20,000, since he didn’t complete the requirements. Arnold did a few raids here and there, but he never attained same glory as before. And the war ended a little under a year after his betrayal. Arnold would spend the remainder of his life in exile in England with little benefits from them. Arnold would live to regret his decision, not because he joined the losing side, but because he truly felt that he made the wrong decision and let his bitterness cloud his judgment. One can only wonder whether we would be celebrating Arnold as a war hero to this day if he hadn’t betrayed his country.

- Milton Lomask, “Benedict Arnold: The Aftermath of Treason,” American Heritage Magazine, 1967, https://web.archive.org/web/20080405211224/http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1967/6/1967_6_16.shtml. ↵

- Willard Sterne Randall, Benedict Arnold : Patriot and Traitor, 1st ed. (Morrow, 1990), 360. ↵

- Willard Sterne Randall, Benedict Arnold : Patriot and Traitor, 1st ed. (Morrow, 1990), 368. ↵

- Clare Brandt, The Man in the Mirror: A Life of Benedict Arnold (Random House,1994), 146. ↵

- Willard Sterne Randall, Benedict Arnold : Patriot and Traitor, 1st ed. (Morrow, 1990), 319. ↵

- Willard Sterne Randall, Benedict Arnold : Patriot and Traitor, 1st ed. (Morrow, 1990), 93. ↵

- Willard Sterne Randall, Benedict Arnold : Patriot and Traitor, 1st ed. (Morrow, 1990), 333. ↵

- Willard Sterne Randall, Benedict Arnold : Patriot and Traitor, 1st ed. (Morrow, 1990), 413. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 151. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 155. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 156. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 157. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 158. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 159. ↵

- Willard Sterne Randall, Benedict Arnold : Patriot and Traitor, 1st ed. (Morrow, 1990), 457. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 169. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 183. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 179. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 209. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 210. ↵

- Brian Richard Boylan, Benedict Arnold : The Dark Eagle, 1st ed. (Norton, 1973), 232. ↵

8 comments

Seth Roen

Benedict Arnold was a good officer, one that we need, and it is a shame that he ended up betraying the United States, something that the British did not like and treated him like an outcast in Great Britain. From how you wrote the article, Gen. Arnold’s actions were both his own and forced by others. And I thought it was interesting that he regarded his actions almost immediately after the war.

Martha Nava

Very well-written and informative article. I never really heard of Benedict Arnold’s life extensively and you did a good job at explaining it very well while still keeping it enjoyable. As the audience, we got to see the events that eventually led to his downfall, and how it could have turned out differently, in a good way. I also liked the cover picture.

Rafael Macedo

Benedict Arnold The former American hero died in London in relative obscurity. He moved to England, though he never received all of what he’d been promised by the British. He later became a successful trader and joined the Continental Army when the Revolutionary War broke out between Great Britain. This post showed everyone how, good research, makes a difference in the end.

Trenton Boudreaux

A well written article on a man I heard about but didn’t have much knowledge of. It’s a shame that Arnold went down the path he did, because as your article laid out, he was a very skilled general. I can honestly see the mindset behind Arnold’s betrayal, because it seemed like congress, and the colonies altogether, hated him. What’s especially ironic is how his seemingly only friend George Washington, was the one Arnold betrayed the most, by lying to him for more supplies to surrender to the British.

Tyler Pauly

I thought it was very interesting that Arnold wasn’t treated very well by Gates and the Congress at the time. That is something I knew nothing about and is an important part of understanding why Arnold would eventually switch sides. I really liked the pictures you had and they really go alongside the story nicely. This article was very in-depth and well done!

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. I actually did some “research” on Benedict Arnold while I was in middle school. I always thought that the continental congress treated him very poorly as well as many of his military compatriots. I never really blamed him for deciding to betray the United States. However, this article provides a more in depth look at Arnold’s character and motivations for committing such an act. For one, he did some very suspect things such as selling rare goods while military governor of Philadelphia. I also would not have used military supplies to carry out my personal ventures like Arnold did. Ultimately, his greed was probably the biggest motivator for him though. 20,000 pounds was a good sum, but ultimately he died penniless in a country that was not his own.

Matthew Gallardo

before this article, i knew very little about the details of betrayal. I had no idea of the court martial and Arnold being charged with 8 different crimes, nor that his wife was as influential as she was in helping him make the decision to switch sides. I am glad that I was able to read up on Benedict Arnold through this article. It’s a very detailed and interesting read, and I’m glad to have taken the time to read it.

Travis Green

What a great, insightful, and informative article about one of the most notorious traitors in history. It’s interesting to look at what he did from a different angle. Which I think is important because he didn’t just wake up one day and decide to betray the continental army. There was a series of events that led him to that decision. Well done I can’t wait to see what your future work will look like.