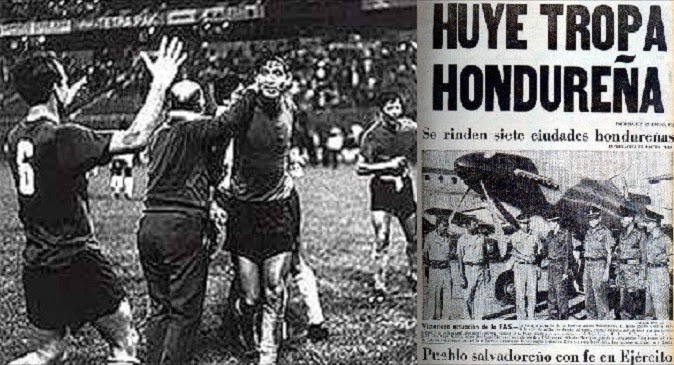

The 1969 play-off match between El Salvador and Honduras (two teams that are not only neighbors but rivals) was filled with anticipation and aggression. This playoff match would decide which nation would be attending the world cup, and which would be staying home. El Salvador and Honduras had each won one match which forced a third, and final, play-off match.1 In the prior matches, fights had broken out between fans in the street and in the stands during the game. But on the day of the final play-off, a much more significant event would take place. The game was scheduled in Mexico City: a third-party country with no bias toward either team. The day of the playoff, El Salvador dissolved all diplomatic ties with Honduras right before the match.

In the first game between the two nations, Honduras won the match 1-0 in its own capital. Some Hondurans stayed outside of the hotel that the El Salvador team had been staying at and threw rocks, set off car alarms and threw firecrackers.2 The 2nd match took place in San Salvador, where the home fans would watch their team win by a commanding score of 3-0. Before the 2nd match took place, the Honduran National team had a security force with them at all times. During the game the security at the stadium was extremely tight with lots of alcohol and weapons confiscated as a security precaution. As the Honduran national anthem played, the home team and fans were extremely disrespectful towards the players and their country. This caused some whiplash for El Salvadorians living in Honduras as their businesses were boycotted and vandalized.3 Leading up to the series of matches, the two nations were in a deep dispute over land reform and immigration. El Salvador was sending its poorest citizens into Honduras so the wealthy could maintain their land.4 El Salvador had a much bigger population than Honduras. Honduras had a population of about 2 million, where as El Salvador had a population of almost 4 million.5

However, they had a significantly smaller amount of land which forced more than 275,000 El Salvadorians to flee into Honduras, causing poverty and crime.6 Honduras accused the El Salvadorians of stealing jobs from the native people of Honduras. But after the 2nd games violence, El Salvador accused Honduras of staying silent while El Salvadorians living in Honduras were raped, murdered, robbed, and oppressed. Neither side was willing to negotiate to the smallest extent, which led to tensions building up even more. In the final match between the two teams, El Salvador won the game in overtime with the score of three to two.7 This caused numerous Salvadorians to be killed in Honduras.8

On July 14th, 1969, almost 3 weeks after the final playoff game, El Salvador bombed targets inside of Honduras. They crippled Honduras by attacking their main airport which left them unable to react to the attack at optimal speed.9 El Salvador then attacked from the ground by marching through the two main roads that connect the countries. Only one day later, the El Salvadorian army had pushed Honduras back over 8 kilometers. The El Salvadorian Army continued to make steady progress. They were nearing the capital city of Honduras, Tegucigalpa, when Honduras finally pushed back. The Honduran Air Force attacked Llopango base. The bombers eventually progressed to Acajutla port, which was important because it was home to El Salvadorian oil refineries. Later that evening huge smoke clouds covered the coast as the the oil refineries were bombed.10

Fearing that the nearing El Salvadorian army would overtake the capital, Honduras called the Organization of American States for help. The Organization of American States (OAS) had an urgent meeting on the evening of July 15th and called for El Salvador to withdraw its troops from Honduras ensuring that its people living in Honduras would not be harmed.11 El Salvador refused, demanding reparations be paid to them and their citizens. El Salvador attempted to further the attack the capital city, but they were unable to proceed with the attack. The previous strike on their oil refineries had destroyed their line of fuels and supplies and they no longer had supplies arriving every other day. Somoza Debayle, the dictator of Nicaragua was also helping Hondurans by arming them with weapons and providing ammunition. The OAS worked night and day in order to provide a cease-fire that would please both parties. Finally, on the night of July 18th, a ceasefire was arranged and became effective two days later.12

Although the cease-fire had been called, El Salvador refused to leave Honduras. They stayed until they were threatened by the OAS with economic sanctions against them. The El Salvador government finally withdrew troops on August 2, 1969. The aftermath of the 100-hour war was anything but slim. More than 2000 civilians were killed, with more than 100,000 immigrants displaced.13 Although they were no longer at war with each other, these two nations peace treaty only came into force on December 10, 1980.14

- Paul Joseph, The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives, 2017 s.v . “Soccer War.” ↵

- Hatcher Graham, Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v “Soccer War.” ↵

- Steve C. Ropp, 1982, “The War of the Dispossessed: Honduras and El Salvador, 1969. Thomas P. Anderson.” The Hispanic American Historical Review, no. 2: 296. JSTOR Journals, EBSCOhost (accessed February 5, 2018). ↵

- Richter, Ernesto, John Beverly, Bob Dash, and Irma Fernandez Dash. “Social Classes, Accumulation, and the Crisis of “Overpopulation” in El Salvador” Latin American Perspectives, 7, 1980 ↵

- Ernesto Richter, John Beverly, Bob Dash, and Irma Fernandez Dash. “Social Classes, Accumulation, and the Crisis of “Overpopulation” in El Salvador”, Latin American Perspectives, 7, 1980. ↵

- Charles Clements, Witness to War: an American Doctor in El Salvador (New York; Bantam Book, 1984). ↵

- Hatcher Graham, Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v “Soccer War.” ↵

- Charles Clements, Witness to War: an American Doctor in El Salvador (New York; Bantam Book, 1984). ↵

- Charles Clements, Witness to War: an American Doctor in El Salvador (New York; Bantam Book, 1984). ↵

- Charles Clements, Witness to War: an American Doctor in El Salvador (New York; Bantam Book, 1984). ↵

- Charles Clements, Witness to War: an American Doctor in El Salvador (New York; Bantam Book, 1984). ↵

- Charles Clements, Witness to War: an American Doctor in El Salvador (New York; Bantam Book, 1984). ↵

- Charles, Clements, Witness to War: an American Doctor in El Salvador (New York; Bantam Book, 1984). ↵

- Charles Clements, Witness to War: an American Doctor in El Salvador (New York; Bantam Book, 1984); and United Nations -Treaties Series, General Peace Treaty Between the Republics of El Salvador and Honduras, 1980, https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/HN-SV_801030_GeneralTreatyOfPeaceElSalvadorHonduras.pdf. ↵

106 comments

Regina De La Parra

I really enjoyed reading this article because soccer is a really important aspect of my culture. Prior to reading this article, I had no idea that soccer could escalate so much that it can cause violence. It is really sad to see an event that brings together friends and family create a lot of conflict between two nations. I really liked how the author was able to explain this issue without being biased. Great job Suvesh!

Timothy ODekirk

This was a massive conflict between Honderous and El Salvador. This article was extremely interesting to read, especially since it was about a conflict between to rivaling neighboring countries, El Salvador and Honderous. What I found interesting is the fact Honderous and El Salvador bordered each other by a matter of roads. That was interesting to me, since a lot of other countries are boarded by oceans or are farther apart from each other. This was an extremely interesting article and was well worth the read.

Kayla Lopez

Soccer fans are very passionate about this sport so this article, though I have never heard about this event, does not surprise me too much. Honduras and El Salvador both take immense pride over their teams but I did not know that this pride would lead to chaos and violence. This was a very well written article and it did a great job of describing an event I had no prior knowledge of.

Rafael López-Rodírguez

This article proves that soccer in Latin America is taken very seriously! I understand the passion the fans have for the game because I experienced the same atmosphere back home with fans acting all crazy and wild. When it comes to international play I get the bad blood some countries have because of previous rivalries and that is what makes the game even better to watch. Who does not like a good rivalry game? But after reading this article the things people did was very extreme and unnecessary over a soccer game.

Andrew Dominguez

Its crazy to think all this violence happened over a game. Before this article i wasn’t aware that such violence can happen from a game which is supposed to be fun.Its interesting to think other countries take their sports more serious than we do, since their events end in violence. The author set up the story very well, explaining how this soccer rivalry would cause so much violence.

Monica Avila

It is extremely shocking to read that a competitive soccer game quickly lead to a major series of violence, including a bomb threat. Sports are usually an outlet for unification among a nation, and I am all for being prideful, but these two nations took it to a whole other level. I was not aware of the previous soccer feud between El Salvador and Honduras, and it is just unsettling to read that the citizens of both nations faced such danger to their safety all because of a soccer game. As a Texas native, I am no stranger to the pride of being a football fan, and to know there are people who feel just as strongly, if not more so, for the sport that is soccer.

Thomas Fraire

The way that a progression of soccer matches transformed into a bomb danger stuns me. I don’t perceive any reason why don diversions dependably quicken for no solid reason. I comprehend there is a considerable measure of enthusiasm in the diversion, however, all that savagery isn’t justified, despite any potential benefits. Notwithstanding, I think it was shrewd to have the third amusement in Mexico to diminish inclination, however that is about the main thing it decreased.

Noah Laing

It’s obvious that Honduras and El Salvador both have very prideful people, it’s sad to hear that that pride would actually push people to take violent actions when things didn’t go their way, in this case, when their countries soccer team didn’t when. Despite these bombings and violent behavior after the games result being unacceptable and devastating, I do think its still fascinating to see the magnitude of how much people can support their sports team, interesting article.

Edgar Ramon

This completely reminded me of Mexico in World Cup matches, the intensity is unreal, we basically invade every stadium and even in domestic (Mexican league) matches, people end up beaten up and taken to prison by cops who are fans of the team opposing your team hahaha. This is a horrible thing honestly, but it’s good to know that at least, when the national team plays, we are all united, and singing with mariachi, drinking together and all that.

Kimberly Simmons

It is so crazy how these two countries were at war over a soccer game. While competition is generally a good thing, it seemed to be much more serious to these rivaling countries. I have never heard about this event, so it both shocked and baffled me that a game is what severed ties between Honduras and El Salvador. In the end, it all worked out…I suppose.