In 1887, wealthy descendants of American missionaries forced the King of the Hawaiian Monarchy, King Kalakaua, to sign a constitution that would disenfranchise many native Hawaiian people, as well as place property qualifications on voters. At the time, those descendants dominated the sugar industry in Hawaiʻi. The constitution would also put an end to the “free and favored entry” promotion of sugar, which appropriated a large tax on sugar exports.1 Native Hawaiians came to refer to this doctrine as the “Bayonet Constitution,” because it was said that armed military forces had threatened the king with guns when he was coerced into signing it. At that point, United States military forces took over troops belonging to the monarchy. Without his troops’ assistance, it became apparent what King Kalakaua’s fate would have been had he not agreed to sign the constitution. In protest to the constitution, native Hawaiian political organizations were established. These groups collectively drafted a constitution that would reverse the disenfranchisement of their people. Although several attempts were made to restore the power once afforded the monarchy through several protests and rebellions, the United States troops continued to prove their dominance. Each attempt to take back power had failed.2

When King Kalakaua died in 1891, his power was relinquished to his sister, Queen Liliʻuokalani. She immediately began working to restore power to the monarchy. After speaking with her constituents, her duty was made clear. Many had prompted her to form and push forward a new constitution. “Two thirds of the registered voters of the islands” had signed petitions demanding her to do so.3 Out of love for her people and for her country she pursued this effort; however, she was soon disrupted. More descendants of missionaries, along with troops from the U.S.S. Boston, who were deployed by Albert Willis, the acting United States Minister, came to overthrow the operations of the Hawaiian Kingdom. They planted themselves into a government building and deemed themselves the acting Provisional Government of Hawaiʻi.

During his presidency, President Grover Cleveland had refused proposals to annex Hawaiʻi. He was skeptical of how the provisional government established its power. Instead, he informally sent Commissioner James Blount to conduct an investigation of the matter. In order for this investigation to begin, the Queen had to sign a document that yielded her executive power to President Cleveland. She voiced her faith that the United States would act in accordance with the law, and agreed to sign. In Blount’s report back to the president, it became apparent that those who composed the provisional government had acted illegally.4

Cleveland was fully aware that under the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the leaders behind the movement to overthrow the monarchy had committed treason when they initially forced the Bayonet Constitution on King Kalakaua. Under the Hawaiian Constitution, it was stated that in order for a constitution to take effect it must first be presented to and accepted by a Legislative Assembly.5 Since this was not done, the Queen was under no technical obligation to recognize the constitution that the missionaries had forced upon her and her people. On October 18, 1893, President Cleveland obligated the United States Minister to begin making settlement deals regarding the restoration of the monarchy. The terms President Cleveland initially listed in return for the full restoration of power included amnesty for the Americans involved in the overthrow.

Cleveland made an attempt to assist their situation by prompting the Queen to grant full amnesty to those that formed the movement against her throne. Granting amnesty to these individuals would mean allowing those that plotted against her to walk free, while also being able to keep the property they acquired on the islands. When asked to do so, the Queen replied “[these] people were the cause of the revolution and the constitution of 1887. There will never be any peace while they are here. They must be sent out of the country, or punished, and their property confiscated.”6 On December 18, 1893, Cleveland announced his thoughts on the Blount Report to Congress. He demonstrated the illegality of the provisional government’s actions and supported the motion to have the Queen’s power reinstated to Congress.7

Queen Liliʻuokalani worked out agreements regarding the whole ordeal with President Cleveland himself. She later came to terms that she would be willing to spare the lives of the Republic leaders, but that their property would be reclaimed by the Hawaiian Kingdom. Their terms were made clear through the Restoration Agreement. However, Cleveland approved the documented agreements without the consent of the Senate, which was later deemed to be beyond his scope of power. Members of Congress quickly accused him of violating the Separation of Powers doctrine and the terms reached between him and the Queen were deemed invalid. In addition, an overwhelming number in Congress believed that the only way for Hawaiʻi’s economy to be successful was if they prompted “continuous expansion of their country.”8 These thoughts appropriated the motion to declare the provisional government’s transition to establish a more permanent institution. They established themselves to be the new Republic of Hawaiʻi on July 4, 1894. That the United States now formally recognized the Republic meant that they could lay claim on all of the crowned lands that had once belonged to the Kingdom, along with the natural resources made available throughout the Hawaiian Islands.

Distraught with the news and compelled to take action against this newly formed institution, a coalition of native Hawaiians began to devise a plan to take back their power through an armed attack. The individuals involved were able to have guns delivered to the island from San Francisco; however, forces behind the Republic caught wind of their actions rapidly. The weapons were seized and all those affiliated with the rebellion were arrested. The Republic later reported that they found guns buried beneath Queen Liliʻuokalani’s garden at her home, known as Washington Place. They arrested her and convicted her of “misprision treason.”9 This act entailed that she knew of the treasonous efforts aimed towards the newly recognized Republic of Hawaiʻi, but deliberately did not report her knowledge of these actions to the government. She would eventually serve a sentence of a combined two years for her alleged crime. But before the trial had taken place the Queen was made to sign a document that would abdicate her of her thrown. Essentially, she would be relinquishing any power she had left. Republic officials made a threat to the Queen that the rebels that had been arrested would be sent to their deaths if she had not signed. In her account of the matter she writes,

For myself, I would have chosen death rather than to have signed it; but it was represented to me that by my signing this paper all the persons who had been arrested, all my people now in trouble by reason of their love and loyalty towards me, would be immediately released. Think of my position, – sick, a lone woman in prison, scarcely knowing who was my friend, or who listened to my words only to betray me, without legal advice or friendly counsel, and the stream of blood ready to flow unless it was stayed by my pen.“10

By 1897, William McKinley had become president, and he was quickly swayed by several annexationists and expansionists. He signed a treaty of annexation and submitted it to the Senate for approval. After serving her sentence, Queen Liliʻuokalani appeared in Washington the day the Senate opened with other delegates from Hawaiʻi to provide testimony and the signatures of native Hawaiians who opposed the movement for annexation. When the delegates left Washington in February, they were successful in having persuaded enough senators to vote against the treaty so that it would not pass.11 Although this was an incredible victory, there were more unfortunate events to come that would detract from the progress they made that year.

In 1898, the United States declared war against Spain. In an effort to gain a strategic position that would gain them the upper hand in the war, they insisted that they needed to use Hawaiʻi as a coaling station for the ships they would deploy in the Philippines. On July 6, Congress passed a joint resolution titled the Newlands Resolution that ultimately claimed Hawaii as a United States territory. Even today, tensions still persist among native Hawaiians who feel strong opposition for Hawaiʻi’s having been annexed. As a way to acknowledge these events and offer an apology, the United States Congress, in 1993, on the “100th anniversary of the illegal overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii,” passed Public Law 103-150. One measure reads,

The Congress … expresses its commitment to acknowledge the ramifications of the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, in order to provide a proper foundation for reconciliation between the United States and the Native Hawaiian people.12

The movement to retain Hawaiʻi was initially pursued as a means of dominating the sugar market and to gain private property. As time evolved, a sense of nationalism dawned over the movement in the midst of the Spanish-American War. It is this sense of protecting American interests that, in part, appropriated the movement. The militarization of the Hawaiian Islands is what eventually enabled the United States to establish themselves as a prominent Pacific power. Congress has acknowledge the actions that led to the annexation and has issued a form of apology in regards to the tension that still persists. They have made it a point to offer their sympathetic words through a Public Law as a way to salvage a relationship between the United States and native Hawaiians. The importance of this relationship lies in the vital role that Hawaiʻi continues to play in the United State’s position in the Pacific.

- Keira Stevenson, Queen Liliuokalani (Massachusetts: Ipswich, 2005), 1. ↵

- Noenoe K. Silva, “Kanaka Maoli Resistance to Annexation,” ‘Ōiwi: A Native Hawaiian Journal 1 (December 1998): 44. ↵

- Noenoe K. Silva, “Kanaka Maoli Resistance to Annexation,” ‘Ōiwi: A Native Hawaiian Journal 1 (December 1998): 46. ↵

- James Blount, “Report of the Commissioner to the Hawaiian Islands,” In 53rd Congress, 2d Sess. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. 1893. ↵

- David Keanu Sai, “1893 Cleveland-Liliuokalani Executive Agreements,” (November 2009): 8. Author David Keanu Sai is a professor of Political Science at the University of Hawaii, and this work of his is from a self-published article, not from a professional peer-reviewed journal. ↵

- David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., “1893 Cleveland-Liliuokalani Executive Agreements,” (November 2009): 5. Author David Keanu Sai is a professor of Political Science at the University of Hawaii, and this work of his is from a self-published article, not from a professional peer-reviewed journal. ↵

- Hawaiian Islands. Report of the Committee on foreign relations, United States Senate, with accompanying testimony and executive documents transmitted to Congress from January 1, 1893,

United States Congress, Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1894. ↵ - Noenoe K. Silva, “Kanaka Maoli Resistance to Annexation,” ‘Ōiwi: A Native Hawaiian Journal 1 (December 1998): 51. ↵

- Noenoe K. Silva, “Kanaka Maoli Resistance to Annexation,” ‘Ōiwi: A Native Hawaiian Journal 1 (December 1998): 56. ↵

- Liliʻuokalani, Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1898), 273. ↵

- Noenoe K. Silva, “Kanaka Maoli Resistance to Annexation,” ‘Ōiwi: A Native Hawaiian Journal 1 (December 1998): 65. ↵

- To Acknowledge the 100th Anniversary of the January 17, 1893 Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, and to Offer an Apology to Native Hawaiians on Behalf of the United States for the Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, Public Law 103-150, U.S. Statutes at Large 107 (1993): 1513. ↵

60 comments

Danielle Rangel

This is a great article topic that needs to be talked about more! I love how the author talks about a piece of US history that is not talked about that much in school. I never knew that Hawai’i had its own monarchy. I think it is interesting to know that Hawai’i had monarchs such as a king and a queen ruler. Overall this was an interesting read and I loved how the author chose to talk about a piece of history that not everyone knows about.

Guiliana Devora

This was a very interesting article and very informative on the history and annexation of Hawaii. I had no idea that Hawaii had a monarchy, let alone the history of how the U.S. ended up making Hawaii a territory. I also liked how the author put into perspective how the queen felt and how people of Hawaii feel about their islands becoming a territory of the U.S.

Abbey Stiffler

I had never heard of the Annexation of Hawaii before. There is much about Hawaiian history This article was very well written and informative. The queen put her peoples’ safety and well being before hers and signed over. I am surprised that the US was in charge of this and kind of goes against the morals I thought we had as a country.

D'vaughn Duran

Hawaiian history with their royal family with annexation. I thought adding the Queen Lili’ uokalani with the excerpt was a great addition in this passage. The queen seemed great with her people till what happened. I didn’t know any history of Hawaii so this article was great to read. You have a great set up of your paragraphs and the make up of all this information.

Ian Poll

There was a great lack of communication on what the leaders of Hawaii can or cannot do in relation to the Senate and the Government. It is sad that major turning points to the Hawaiians and their power were controlled by threats to the people of Hawaii. It was interesting to see how the Hawaiians were going to retaliate but failed before any major progress was made. Overall, an interesting article and well written.

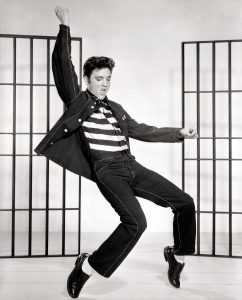

Danielle Sanchez

This was a great article which contained images that brought the story to life. King Kalakaua signed a constitution in 1887 that disenfranchised many native Hawaiian people. This constitution would end the free and favored entry promotion of sugar. This put a large tax on sugar exports. The constitution came with armed military forces which threaten King Kalakaua at gun point to sign. After the king passed on so did his reign. Overall, great article!

Tabitha Babcock

What an interesting read! This article was clearly well-researched, and I thought the inclusion of the block quote from the queen was so powerful. She was definitely a force to be reckoned with. The way congress handled this situation is deeply disappointing to me. First, they get upset because Cleveland goes over their heads. Then, they realize they were wrong, and instead of giving Hawai’i back to the native people and allowing them to reestablish the monarchy, they send a lame apology. Ridiculous.

Clarissa Liscano

I learned a lot about the different factors that went into Hawaii’s history and annexation, as well as about the terminology. Queen Lili’uokalami did her best to protect her people by surrendering the throne. Another intriguing fact was that unlike on the North American Continent, Hawaii was a recognized kingdom rather than a confederation of tribes. Amazing and well written article.

Veronica Lopez

Interesting article. It really explains how easily a country can be taken over if they have less power than the country who wants to take over. The annexation of Hawai’i is a great example of this. On the other hand, I was really surprised that Hawai’i had a queen. I didn’t think the natives would allow that because it was the 1890’s.

anthony Dinh

This essay was very interesting, we don’t really hear a lot about Hawaiian history, so everything in this paper is new and is very interesting. The pictures really help with who these people actually are, and how Hawaiian people actually looked. The paper was written very smoothly and easily understandable. Great paper overall!