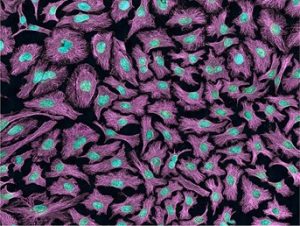

In February 1951, Dr. Lawrence Wharton Jr. collected cancerous cells from a growing tumor in Henrietta Lacks’ cervix.1 Little did he know that her cells, dubbed HeLa cells, would change the world. Dr. Wharton sent those samples to a pathologist, Dr. George Gey, in the Johns Hopkins Hospital Complex, who sent them to one of his lab assistants, Mary Kubicek. Kubicek did as she was taught, slicing the samples into one-milimeter squares, using a pipette to drop them into chicken blood-clots that she had previously set aside, and covering each clot with culture medium before sealing and labeling them. She labeled them as she labeled most cell cultures, with the first two letters of the first and last names of the patient that they had come from. She carefully wrote “HeLa” on each test tube and brought them to Gey’s incubator room, where the other cell cultures were all stored.2 Gey’s goal in his research was to find a way to keep human cells alive outside of the body, and until this moment, he had been unsuccessful.3

After only three days, Kubicek noticed the HeLa cells were not only surviving, but they were growing, with an intensity never seen before. Another day passed, and they had doubled. This pattern continued as her cells grew to fill as much space as they could. Soon after discovering this, Gey started telling his closest colleagues that he may have grown the first immortal human cells, and even offered to share them.4

In testing Lacks’s cells, doctors found that she had human papillomavirus, more commonly known as HPV, which is one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases. Only 10% of people with HPV infections develop cervical cancer, and she had been one of the unlucky few. HPV cells are known to divide rapidly and forever, but humans possess sentinel cells, made up of proteins P53 and Rb, which attack HPV cells enough to keep them in check. Lacks’s body lost the ability to produce these sentinel cells, causing her cells to grow indefinitely and become “immortal.”5

Dr. Gey began to share these samples with scientists across the world. As long as they would be used for cancer research, he would ship them for free, which was a complicated process. They would have to be sent by plane, kept at a certain temperature, and picked up from the landing site as soon as possible by the receiving scientists. Because HeLa cells could multiply infinitely, they were very helpful to researchers. They would be able to test different things on the same cells without worrying about losing the cells, because there would just be more.6 Her cells went on to be mass produced by researchers Russel Brown and James Henderson at Tuskegee University. They started up the HeLa Project, and had the goal to ship at least 10,000 cultures per week to other laboratories. Not only did they reach this goal, but they doubled it. At their peak, they were shipping out 20,000 cell cultures, and by 1955, they had shipped around 600,000 cultures. These cell cultures had massive breakthroughs in studies for the polio vaccine, as HeLacells were extremely susceptible to poliovirus. This gave scientists the opportunity to test different vaccines for polio with the same cells to see the success of different vaccines without having to worry about losing the cells, since they could just make more.7 Their use of HeLacells led to major breakthroughs in eradicating polio. This was just one of the breakthroughs that occurred thanks to HeLa cells, yet still, nobody knew the woman behind them.

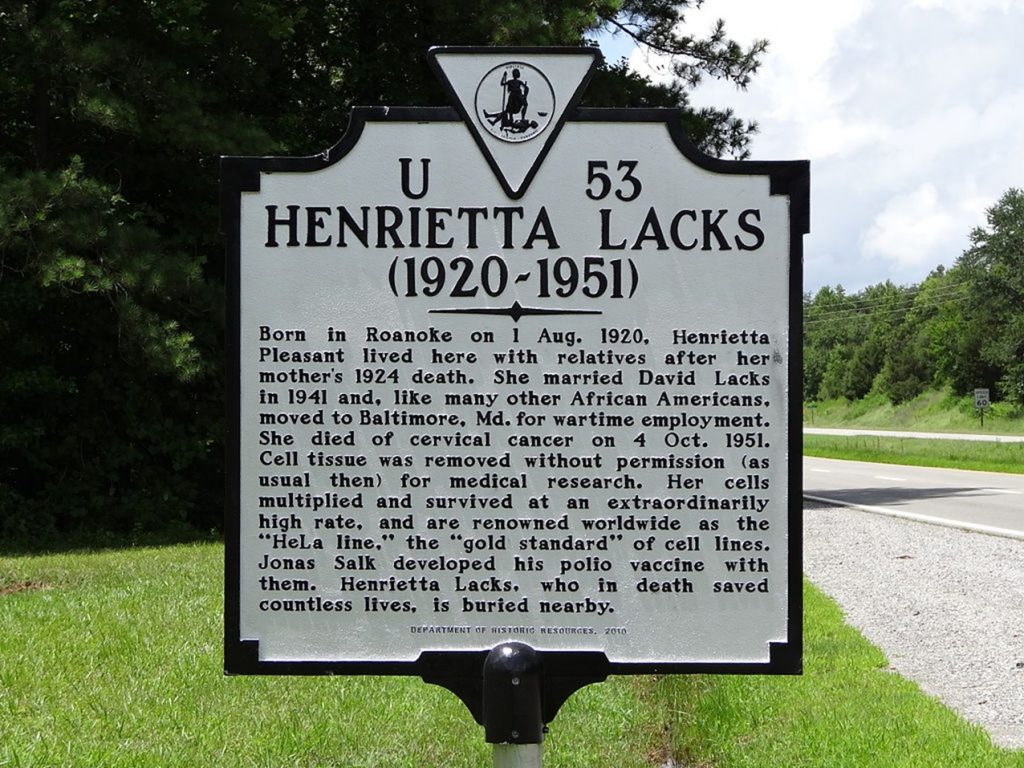

Before Rebecca Skloot’s book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, many were unsure of the name of the woman these cells even came from. Most commonly, she was referred to as Helen Lane or sometimes even just HeLa. She never knew her cells were special because she died shortly after the samples were taken. Skloot describes hearing about HeLa cells briefly in a lecture during college. She ran home, wanting to research the woman behind these cells, but in every search on the internet or in books she’d look at, any details about the woman behind the cells had major inconsistencies.8 This was her inspiration to write the book; she wanted Lacks to get the recognition she deserved for what her cells did for science, even if Lacks wasn’t around anymore. Since the publication of the book, more people know the name Henrietta Lacks, but even then, when I would mention her to professionals at my university, many still didn’t know who she was or what her cells did for science.

Deborah Lacks, Henrietta Lacks’s second daughter, asked a perspective-changing question about what scientists did with her cells. “If our mother’s cells done so much for medicine, how come her family can’t afford to see no doctors? Don’t make no sense. People got rich off my mother without us even knowin about then takin her cells, now we don’t get a dime.”9 It was more than forty years later when Skloot began her research and the Lacks family finally got recognition, but in this recognition came a large ethical debate. In March 2013, a German research team posted the full HeLa genome for free access to anyone who was interested. This didn’t break any laws or rules, but it did upset the Lacks family. It was easy access to the heritable aspects of Henrietta’s DNA and could lead to harmful inferences about her descendants. In only a few days, the Lacks family contacted the NIH’s National Center for Biotechnology, where the genomes were published, and the information was removed from their website. They worked with the Lacks family to find the best course of action, ultimately deciding to form a panel that had some Lacks family members to judge if the genome sequences should be shared or not. This is still being implemented to this day and was necessary since Henrietta’s cells were stolen from her. It also brought to attention the revision necessary to the laws surrounding the consent needed to take samples from a patient.10

Not only were HeLa cells in the research for the poliovirus vaccine, but they were also used for many more scientific studies. HeLa cells were sent to space to test the effects of zero-gravity on human cells, paving the road for astronauts in the future.11 Her cells were used to discover how Human Papilloma Virus can lead to the development of cervical cancer, which also led to the development of some of the first anti-cancer vaccines.12 Her cells have been used for many other studies that end with Nobel Peace Prizes, and many of these achievements are listed on the National Institutes of Health website.

If it weren’t for Henrietta Lacks, biomedical science would have never evolved to where it is now. Scientists have been able to create vaccines for major diseases across the world due to HeLa cells. They’ve been able to save lives, create life, and help millions. Undeniably, every person in the United States has been helped by Henrietta Lacks. Henrietta’s story raises many ethical questions about consent in science and has been the catalyst for changes throughout decades in ethics surrounding scientific research. The achievements made due to the discovery of HeLa cells stand as symbols of the triumphs that come from scientific progress.

- Tamara Dunn, “Henrietta Lacks,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 6, 2024), Research Starters, https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=502d13aa-9e65-32c7-b192-1deca7f1e289. ↵

- Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Crown Publishers, 2010), 34-38. ↵

- Tamara Dunn, “Henrietta Lacks,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 6, 2024), Research Starters, https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=502d13aa-9e65-32c7-b192-1deca7f1e289. ↵

- Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Crown Publishers, 2010), 40-41. ↵

- Ivan Martinez, “What Are HeLa Cells? A Cancer Biologist Explains,” Credo Reference, June 2022, https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6NDU1NDExMg==. ↵

- Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Crown Publishers, 2010), 57-58. ↵

- Timothy Turner, “Development of the Polio Vaccine: A Historical Perspective of Tuskegee University’s Role in Mass Production and Distribution of HeLa Cells,” National Library of Medicine National Center for Viotechnology Information 23, no. 4 0 (November 2012), https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012.0151. ↵

- Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Crown Publishers, 2010), 1-5. ↵

- Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Crown Publishers, 2010), 9. ↵

- Kathy L. Hudson and Francis S. Collins, “Family Matters,” Nature 500, no. 7461 (August 8, 2013): 141–42, https://doi.org/10.1038/500141a. ↵

- N. N. Zhukov-Verezhnikov, Results of Microbiological and Cytological Investigations on Vostok Type Spacecraft (Itogi Mikrobiologicheskikh i Tsitolo- Gicheskikh Issledovaniy Na Kosmicheskikh Korablyakh Tipa ’ “vostok”’), 1964, http://archive.org/details/nasa_techdoc_19650002618. ↵

- “A New Type of Papillomavirus DNA, Its Presence in Genital Cancer Biopsies and in Cell Lines Derived from Cervical Cancer,” accessed April 10, 2025, https://www.embopress.org/doi/epdf/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01944.x. ↵

8 comments

Alejandro Rubio Chappell

I never realized just how much one person’s cells could impact the world until I read this. The way you explained Henrietta Lacks’s story made it feel real—not just a science fact, but a human story. Her cells helped with vaccines, cancer research, even space studies, and yet her family had no idea. It’s powerful and heartbreaking at the same time.

rmanzur

This article was both powerful and thought provoking. It highlighted the ethical issues behind Henrietta Lacks’ story while also recognizing the massive impact her cells had on science. The writing was respectful, informative, and engaging throughout. It’s an important reminder of how medical progress must always be paired with consent and justice. Truly an impactful and eye opening read.

TJ

I found the article’s mix of scientific breakthrough and ethical discussion really engaging. The step by step account of how Dr Gey and Mary Kubicek discovered the immortal nature of HeLa cells made the science clear and fascinating. I also appreciated the focus on Rebecca Skloot’s efforts to restore Henrietta Lacks’s name and the family’s reaction when they learned about the genome release. The piece balanced advances in medicine with the human cost of research really well.

Micaella Sanchez

It was an interesting read. I had no idea that there was even a chance of getting cancer from HPV This can also be very insightful when it comes to studying human health in the future, but I do not think that they went about this in the right way. I am glad that you wrote about this; it sheds light on the injustice of not being credited for her cells, because they definitely did benefit science.

Carlos Flores

This article does a remarkable job of highlighting the profound impact Henrietta Lacks and her immortal HeLa cells have had on scientific progress. It beautifully weaves together her story with the breakthroughs in medicine and ethics, emphasizing both the personal and scientific significance of her legacy. The focus on the ethical considerations surrounding consent and recognition is crucial and well articulated. Kudos for bringing attention to such an important and often overlooked story in science.

Meadow Ayala

This was such a powerful and emotional read. It’s heartbreaking to know that Henrietta Lacks gave the world so much without even knowing it — and even sadder that her family struggled for decades without recognition or support. Her story really shows both the incredible power of scientific discovery and the deep need for ethics and respect in research. Henrietta’s impact on medicine is beyond words, but the fact that her family’s voice is finally being heard is just as important. It’s a reminder that real people are behind every breakthrough, and they deserve to be honored and remembered.

Rachel Johnson Keith

This was an interesting read. I was aware of Henrietta Lacks, but there were quite a few bits of information here that I didn’t know. Thanks for enlightening me!

Pedro Alvarez Rivero

Very nice article. I like the mix of history and science in it. Although they basically steal her cells I am kind of glad they did. It sounds bad but her cells do a lot of good for humanity. However, I do believe the doctors should have tried to contact her to pay her for her contribution to science.