Throughout the history of civilization and humanity, the question of right and wrong regarding a moral code has been a topic of discussion, as it struggles to be universalized. Moral relativism argues that the vast array of differing religions, cultures, and mindsets ensure the impossibility of a “just” society.1 Because of this, historical plights, such as the era of Jim Crow with the violence it ensued, have once been justified under impaired morality, and standards of justice.

“Separate but equal” was praised, and “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” was spoken publicly by politically influential individuals without questioning its public acceptance, further emphasizing the societal norm of the morally abnormal.2 “Whites only” signs were apparently necessary in every public establishment during the 1940’s, as well as “sundown towns” –created to prevent criminal violence that presumably emanated from African Americans– systems of which were enforced using violence.3 Despite the embrace of impaired justice and societal norms by the majority, the “moral judgments are true or false only relative to some particular standpoint” plants a seed of countercultural movements and figures of resistance, which was sparked in Martin Luther King Jr.1 Residing in the heart of segregated southern U.S. in Atlanta, Georgia, Martin Luther King Jr., son of a Baptist minister and brought up in a household saturated in resilience and a profound sense of justice, co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), served as a beacon for hope regarding racial justice and the eradication of segregation, as well as racially motivated violence.5

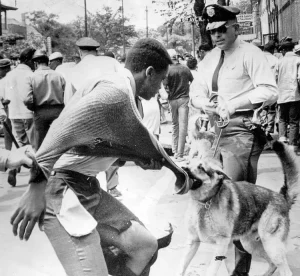

King dedicated his life’s work to leading movements against racial discrimination and encouraged resistance, addressing violence and cruelty against African Americans. King led the Montgomery Bus Boycotts of 19556 following the altercation with Rosa Parks, and the Albany Movement of 1961, which garnered countercultural outcry and support.7 Despite progressive success to King’s cause in these cities, King’s “Macedonian” call compelled him to initiate resistance in places outside of his own town that still harbored segregation. The knowing of injustice somewhere without a rebutting voice, knowing somewhere people still lived in fear, walked in fear, couldn’t sleep out of fear, and couldn’t exist effortlessly out of fear, nagged at King’s consciousness. Having a track record of nearly 50 racially motivated bombings, as well as violence against African Americans by the Ku Klux Klan, “Bombingham” garnered King’s attention.8 Not long after, Birmingham was a target for the pursuit of desegregation and racial equality. Being under the rule of the Commissioner of Public Safety, Bull Connor, the habitual use of excessive force against protesters and activists, as well as the adopted values in opposition to integration and desegregation, Birmingham and Connor could not be permitted to relish in dehumanizing and immoral practices any longer.

Revolving around King’s mind were the lived experience of daily violence, the images of fellow black neighbors being beaten (or even killed), and the inheritance of distress that is passed down to their children, feeding King’s urgency for the nation to awake from its avoidance of the injustice at hand. King’s outcry ached to not only be noticed, but for it to be so overwhelmingly inescapable that it would need to be addressed.

Prior to any action, King needed to collect “the facts” of Birmingham and the habits there as a means to prevent a lack of preparation and attain sufficient cause for initiating a protest in Birmingham and being known as “the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other,” the need for clamor was more than sufficient.9 Despite the severe offenses committed against Black individuals in Birmingham that would call for harsh retaliation, King advocated commencing systematic change by attempting negotiations before initiating any disruptive action. King’s pursuit of peace and non-violent confrontation was to avoid putting more brush to an already harmful fire. The September 1962 meeting between civil rights leaders, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, and Birmingham’s merchant leaders was a peaceful step forward in negotiation and ultimately desegregation.10 Verbal communication and parley provided a platform for marginalized voices to be heard and for societal change to commence. The meeting consisted of a promise of removing marginalizing “whites only” signs, as well as other claims for a trajectory of change. But was that too good to be true? Despite the assurance, a promise without action is hollow and serves only as a means to quiet the loud opposition. Days, weeks, and months went by. Signs remained in their places above door frames, fountains, rooms, and any signs that were taken down were put back up in their place after a short time.

Disappointment and licks of betrayal plagued the oppressed of Birmingham, as what may have been perceived as a failure to many was a green light for retaliation for King, stating “a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.”9 Failure to uphold their respective end of the negotiation only fueled unanimous outcry for racial equality further, prompting King and supporters of his resistance to respond to Birmingham’s merchants’ indirect message. Although direct action from King and affiliates was imminent, seeing that peaceful communication was ignored, this would mean inevitable resistance from Birmingham and Connor. Moreover, Connor’s known abuse of power and forceful hand against activists and movements may have led to questioning of possibly severe risks. What of the lives of those protesting? What of the plan for a peaceful approach? King stated, “‘Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?” “Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?”9 The “risks” and the danger to the lives of black individuals and King faced were no different than the risks already taxed upon their daily lives. The difference between the complementary peril that would follow public outcry and the dangers that were being presently lived is that protest would serve for the purpose of the greater good and societal progression. Thus, “Project C” was born.

Gathered together in a hotel room in the segregated Gaston Motel, King and leaders of the resistance orchestrated a campaign against racial inequality and violence, strategically set after the change of political power in Birmingham, in order to avoid being ignored. The protests, taking place during Easter shopping season, were designed to garner attention through monetary impact, causing “a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored.”9 The “Birmingham Manifesto” was brought to the national spotlight and advertised to the people of Birmingham, urging them to “believe in the American Dream of democracy, in the Jeffersonian doctrine that ‘all men are created equal and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among these being life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’”14

The pent-up tensions of constant marginalization, abuse of a demographic, dehumanization, and the stripping of human dignity ignited a need for rebellion, loud objection, and weaponization of peaceful protest. King and African Americans could no longer be ignored and sought to make sure they could no longer be ignored by the people of Birmingham and Connor either. The discouragement of protest from the white clergymen of Birmingham, the question of whether support would have a sizeable turnout, or the possible threat to others’ lives swirled around King’s mind the night before the first march on April 6, 1963. However, none of these possibilities prompted him to stray away from his resilience towards the defiance of segregation and racism, despite the failure of the march, as Connor seized the protest within three blocks. Men and women were restrained and were arrested, marking the march as unsuccessful, and perhaps in the eyes of some, pathetic.

“When you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky.”9

This swirled around King’s mind as well, prompting him to disregard failure and the fear of it and step on that pavement again to march on April 7th. The failure of the second march was increasingly violent in nature and further motivated racial persecution. The families, women and men, were restrained, chased, and bitten by canine units, and hit in efforts to silence them. The violence of the second march swayed leaders of the resistance to question Project C as fear of failure and danger seeped into their consciousness, conveying to King that revaluation was necessary. Frustrated and weighed down by the sense of imminent defeat, allies questioned the probability of the resistance’s success, looking to King for answers and a course of action.

“When you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments.”9

Fear. A constant throughout African Americans’ lives for as long as King could remember, and a tactic that was served to him by an injunction obtained by the city to eliminate marches and protests, of which he was not going to let dissipate what had been sparked in him. Legal or not, “one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws,” fueling King’s decision to march on Good Friday, pushing legality limits, and taunting Connor and the racists extremists, disregarding the wishes of the white moderate.9

The yearning for freedom and desegregation, and the desire for the acknowledgment of being an equal human being, despite the color of their skin, propelled King to march once again, despite the imminent threats to the safety of his followers and his own life. The need for acknowledged outcry encouraged King to try once more, “compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own hometown. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.”9 King stepped onto the paved road with unwavering courage, loud opposition, and a yearning for peace and equal treatment regardless of skin color. A yearning for Birmingham’s freedom and desegregation, of unity and equal community, a pursuit of a dream that resulted in his own arrest, presuming the success of Connor and the white supremacists.

Cell walls surrounded King while his black brothers and sisters protested on his behalf, walls dripping with failure and smelling of defeat. King broke the law and was now more than ever perceived as a criminal, reduced to the mold he was prejudiced of. Isolated and unable to be heard by the public, his pleas echoed off the stone walls, being heard only by himself.

“Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever.”9

Connor may have silenced King’s voice and presence, but he was unable to strip him of his written word. King, sitting in his cell, began to write a letter aimed not to victimize himself, but instead to expose the nation to the realism of their immoral society. King addressed the white clergymen of Birmingham regarding the questioning of his “outsider” status in Birmingham, claiming “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial ‘outside agitator’ idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.”9 He addressed the diluted perception of the severity of injustice, stating, “You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes.”9

He addressed the “untimely” organization of protests, declaring, “For years now I have heard the word ‘Wait!’ It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This ‘Wait’ has almost always meant ‘Never.’ We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that ‘justice too long delayed is justice denied.’”9 He addressed the motives for resistance, professing, “Hence segregation is not only politically, economically, and sociologically unsound, it is morally wrong and awful. Paul Tillich said that sin is separation. Is not segregation an existential expression of man’s tragic separation…? Thus it is that I can urge men to obey the 1954 decision of the Supreme Court, for it is morally right; and I can urge them to disobey segregation ordinances, for they are morally wrong.”9 King exhorted the “white moderate,” criticized the supposed church, and stripped the impaired belief of justice that Birmingham was desensitized to. King exalted the crime against the degradation of human dignity and urged the country to become aware of the racial atrocities that had become the norm for far too long. Despite setback after setback, apparent impossibility, and being silenced by those enforcing impaired justice, King’s voice was heard.

The emotion embedded in every pencil stroke in King’s letter was not meant to attain sympathy, but instead was meant to create an infection of desire. The thing about infections? They’re contagious. The extensive account of the violence, discrimination, dehumanization, and injustice that had been long present in Birmingham in the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” inspired James Bevel, associate of the SCLC, to take part in this adaptation of a Macedonian call for desegregation and equality in Birmingham.10 With diminishing support and action following King’s arrest, the resistance needed to relay an inescapable and impactful message to the people of Birmingham and the nation. Bevel and King needed to appeal to the U.S. emotionally, they needed the nation to feel compelled to join the fight against immoral law. Upon consideration, Bevel organized the Children’s Crusade, a march consisting of protests formed by children, ranging from over 1,000 7-18 year old kids.25 The children stepped out onto familiar pavement for a protest, Connor and the white supremacists ready and armed. Surely they wouldn’t hurt children, colored or not? Yet, the crusade resulted in Connor releasing canines to attack the children, the usage of high-pressure hoses that tore the children’s clothing and bruised their skin, as well as the children’s arrests.25

The horrors of Connor and Birmingham’s violent practices, which were broadcast nationwide, attained national attention and scrutiny as the horrific images stimulated the country’s moral responsibility to act. Images of police brutality, enacted upon children, colored or not, shocked the nation, forcing U.S. citizens of the exposure to its own tremendous distance from morality. The infectious revival of anti-discriminatory efforts did not stop there and continued. Though, so did the malice of Birmingham, exemplified in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four young girls, triggering the memory of the atrocities of the Children’s Crusade.10 The bombings and continued violence against the protests of desegregation attained national attention, as well as presidential.

The horrors and inhumane practices conducted in Birmingham caused national outrage that caught the attention of President John F. Kennedy. Kennedy was obliged to send representatives to Birmingham to desegregate the city, as well as ordering Connor and other Birmingham commissioners to resign.5 The endless battle over the span of months, the constant perception of failure, the doubt of the resistance, all have been discredited. The voices of those previously shunned were being supported nationally. The cry of African Americans in Birmingham were finally heard, and lawful segregation in Birmingham had finally come to an end. Although at the expense of the little freedom he had, King’s arrest, his tenacity for civil rights, and his vigor for peaceful direct action propelled societal change and a newfound search for moral justice in not only Birmingham but around the nation. King’s response to his adaptation of the Macedonian Call in addressing “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” resulted in the incarnation of passion for equality and peace, differing from the societal norm of violent segregation and daily terror.9

King’s courage and selfless action, along with transcendent resilience, ultimately contributed to the progress of resistance to unjust law enforcement and the eventual creation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination based on color or race, and bringing an end to segregation nationwide. Despite being constantly dissuaded by oppositions and allies, King could not be silenced or deterred, intimidated or restrained. The possessed dogma that “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed” resulted in a pivotal narrative of experienced racial persecution, fueling loud opposition, protesting, and succeeding in societal change and equality for generations to come.9 Looking up at the tops of door frames, residing in the place of formerly bitter signs that glowed of inferiority, “entrance” and “exit” could be seen, regardless of skin color.

- “Moral Relativism,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed May 4, 2025, https://iep.utm.edu/moral-re/. ↵

- George Wallace, “Inaugural Address,” Alabama Department of Archives and History, accessed May 4, 2025, https://digital.archives.alabama.gov/digital/collection/voices/id/2952/. ↵

- James W. Loewen, Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, Zinn Education Project, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/sundown-towns/. ↵

- “Moral Relativism,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed May 4, 2025, https://iep.utm.edu/moral-re/. ↵

- “Martin Luther King, Jr.,” NAACP, accessed May 4, 2025, https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/martin-luther-king-jr. ↵

- “Montgomery Bus Boycott,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University, accessed May 4, 2025, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/montgomery-bus-boycott. ↵

- “Albany Movement,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University, accessed May 4, 2025, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/albany-movement. ↵

- “Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument – Park Archives,” National Park Service, accessed May 4, 2025, https://npshistory.com/publications/bicr/index.htm. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- “Project C – The Birmingham Campaign,” Alabama African American History, accessed May 4, 2025, https://alafricanamerican.com/project-c-the-birmingham-campaign/. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- “Birmingham Manifesto,” Teaching American History, accessed May 4, 2025, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/birmingham-manifesto-3/. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- “Project C – The Birmingham Campaign,” Alabama African American History, accessed May 4, 2025, https://alafricanamerican.com/project-c-the-birmingham-campaign/. ↵

- Alexis Clark, “The Children’s Crusade: When the Youth of Birmingham Marched for Justice,” History, October 14, 2020, last updated April 15, 2025, https://www.history.com/articles/childrens-crusade-birmingham-civil-rights. ↵

- Alexis Clark, “The Children’s Crusade: When the Youth of Birmingham Marched for Justice,” History, October 14, 2020, last updated April 15, 2025, https://www.history.com/articles/childrens-crusade-birmingham-civil-rights. ↵

- “Project C – The Birmingham Campaign,” Alabama African American History, accessed May 4, 2025, https://alafricanamerican.com/project-c-the-birmingham-campaign/. ↵

- “Martin Luther King, Jr.,” NAACP, accessed May 4, 2025, https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/martin-luther-king-jr. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Learning for Justice, accessed May 4, 2025, https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/general/Letter%20from%20Birmingham%20Jail%20MLK.pdf. ↵