One man’s dream to make cars affordable didn’t just change how people traveled; it reinvented how the world worked. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the town of Detroit in the state of Michigan was a small but expanding industrial center situated on the banks of the Detroit River. The roads were filled with horses and trolleys and a few pricey automobiles that only the rich people could buy. The automobile was considered a luxury good and a curiosity beyond the means of ordinary Americans. But for one young engineer named Henry Ford, such a limitation presented a challenge to be overcome.

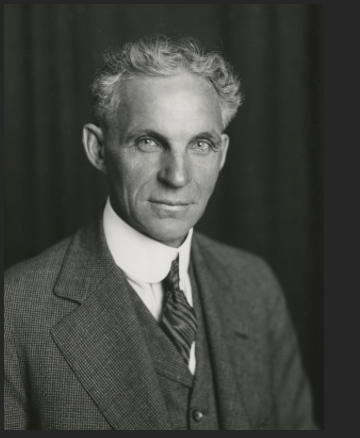

Henry Ford was born in 1863 to a Michigan farm family. As a young boy, Henry had been fascinated with machinery. As a young man, he repaired watches, machinery, and engines. He even became an engineer at Edison Illuminating Company, which allowed his skills and interests to thrive. During the day, he worked; at night, he constructed small gasoline engines in a shed at the back of his home.1 Henry had a dream unlike anyone else. This dream involved creating a car that could be owned by everyone, not just by the elite. A simple, strong, and affordable car could give ordinary people the gift of transportation.

A setting such as that offered by Detroit allowed for the fulfillment of Henry Ford’s dream. A structure of machine shops and metal workers had been established in the city. The spark of innovation had been hovering in the atmosphere. It only had to ignite in the right mind.2

The Birth of the Ford Motor Company in 1903

In 1903, Henry Ford formed a small team of investors and established the Ford Motor Company in a wooden factory that he rented on Mack Avenue in Detroit. His burning desire was to show the world that his “car for the masses” could be a market success. At that time, car makers were creating high-priced vehicles that were handmade for the wealthy.3 Henry’s initial efforts at manufacturing vehicles, such as the Model A and Model N, had potential, although they were still out of the price range for the majority of people.4

The Dream of Affordability

Ford’s goal was to make reliable vehicles. However, his ambition didn’t stop there. He also wanted to transform the way these cars were manufactured. In his thinking, instead of constructing every automobile individually, he wanted to develop identical parts to be easily assembled. Henry Ford’s beliefs and ideals stood out when he thought that the best car should be within reach of the average man.5

The Model T

In October 1908, the Model T rolled out. This sturdy car had a four-cylinder engine and was constructed with high-strength vanadium steel. This car could withstand rough roads and drive easily. Even for $85o, it appealed to potential customers because it offered them a bargain; however, it was still expensive for many. Orders poured in immediately. In a short span of a few years, Henry Ford could not produce enough automobiles to satisfy the demand.6

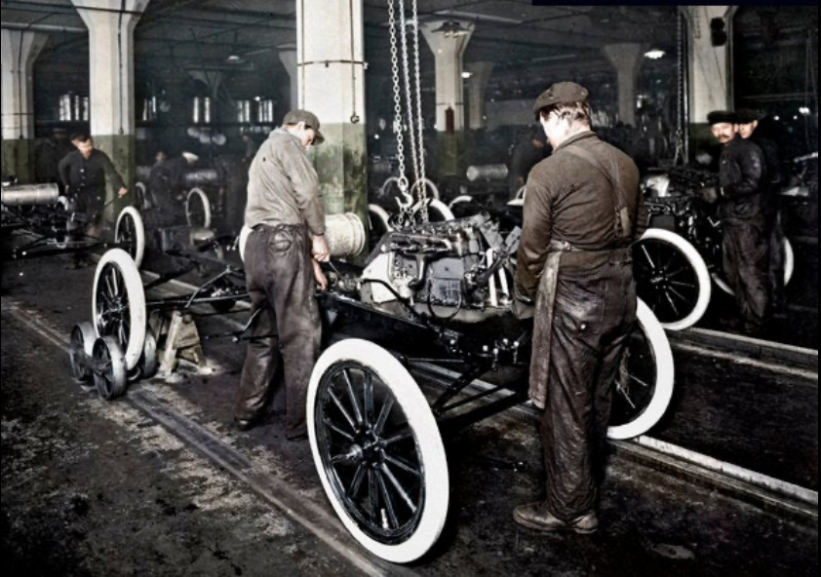

To meet the demand, Henry Ford and his engineers had to look for solutions to improve their productivity. Noting the method used at meatpacking plants, which had animals carried on conveyor belts in such a way that the products were brought to the workers to assemble. In December 1913, the first functional assembly line went operational at Henry’s Highland Park plant. It took just ninety-three minutes to assemble what had taken twelve and a half hours to assemble before.7

This innovation brought a radical change. The production costs came down drastically. The price of the Model T decreased to $55o in 1914 and to $300 in the 1920s.8 Henry Ford’s innovation of standardization, or manufacturing similar parts with less waste, is the backbone of current industrial production.

Labor tension turnover

Nevertheless, there was a price to be paid for this success. The pace and repetitive nature of the assembly line led to exhausted workers. Each worker did the same job for ten hours a day, and the workplace was loud, hot, and timed to the minute. Labor turnover soared to 380 percent in 1913.9 Henry Ford quickly understood that increased production meant little if there was not a loyal workforce.

The $5 a day revolution in 1914

On January 5, 1914, the nation was shocked when Ford announced he would double the wage rate from $2.34 to $5 per day and cut the working day to eight hours from nine. It led to the media calling him a “mad capitalist” with prognostications of bankruptcy. Actually, his policy altered the economics of industrial labor. Productivity soared over 40 percent in a short time. Turnover became almost nonexistent.10

But the influence did not merely stop at the factories of Ford. Thousands of workers poured into Detroit from the countryside of America and other countries. This was due to the high wages they would receive. Workers had money to buy the products they manufactured. Workers at the factories of Henry Ford could also be his customers. Businesses in the town boomed with money as it circulated. The GDP of the town of Detroit grew. The town became one of the fastest-growing cities in the world.11

Detroit Transforms

By 1920, “The Motor City” had been established in Detroit. “New neighborhoods developed to accommodate workers at expanding factories. Model T’s filled the streets. The associated industries of steel, glass, rubber, and fuel had to expand to satisfy the demand for cars. Between 1910 and 1930, the population of Detroit had tripled to over 1.5 million. It began in 1910 with 465,000.”12

At the end of 1913, the first Model T rolled out of the fully functional assembly line at the Highland Park Plant. Cars moved effortlessly through the assembly line. Each worker had been given one motion to carry out. It had taken a team of men over half a day to accomplish the job. It now took less than two hours.

That moment was Ford’s triumph; the fulfillment of his dream began during his days at Edison Illuminating: a car for the common man. Shortly after, one of his employees purchased a Model T, driving around in the very machine he had helped build.13 To Henry Ford, it meant not merely just a sale; it meant his dream had been achieved. The automobile was no longer a symbol of status; it was now a symbol of the rights of modern life.

Henry Ford’s accomplishment was not only a testament to innovation in technology but also a symbol of economic transformation. Industrial production in Detroit increased exponentially with the growth of its gross domestic product.

By the 1920s, Detroit had become the “symbol of America’s progress.” Its skyline was dotted with smokestacks, and the sound of machinery filled the air. Families who had been living in poverty were able to afford homes and transportation with the help of Ford’s wages. “The Model T became more than just a means of transportation; it became a symbol of independence and mobility.”14

The economic effects were remarkable. Detroit’s manufacturing base led the country in production. By 1929, the automobile industry alone had contributed over 7 percent to America’s GDP.15 Henry Ford’s policies had not only made him wealthy but had also increased America’s middle-class population.

Despite the success that came with it, there were challenges. Henry Ford’s model of efficiency promoted continuous repetition and discipline, at times leading to worker strikes. The town’s economy relied on car manufacturing. Nonetheless, during this golden age, the transformation in Detroit was undeniable.

Henry Ford’s innovations also transformed industries across the globe. This moving assembly line concept was adopted in factories across the world, as well as the shipyards in England and tractor factories. As Robert Brinkley remarks, “Ford became less a businessman than a cultural force.”16 Indeed, Henry Ford’s policies altered the way humanity organized its workers and production activities.

Despite his achievements, there were weaknesses to Ford. These included his non-acceptance of trade unions and his troublesome views in regards to politics. Nevertheless, his economic philosophy, “efficiency with fairness,” stood the test of time. Henry Ford thought that business had to serve to profit as well as the people. This is evident in his sayings, such as “The business of America is service.”

By the end of the 1920s, the Model-T had penetrated every nook and cranny of the world. It had been used by farmers to reach markets, doctors to reach patients, and families to explore new places. The wealth, size, and power of Detroit had increased drastically. Henry Ford’s dream had not only transformed a sector but had altered the fabric of the modern world.

Although he had retired from the day-to-day activities of his business in the 1940s, his principles continued to form the basis of industrial production. The assembly line production, which is now automated and expertly developed, still incorporates the principles laid out at Highland Park. As historian Steven Watts explains, “Ford’s genius is not just in his machinery but in his imagination. His idea was that technology could improve ordinary life.”17

Today, when economists reflect upon the early twentieth century, Henry Ford’s economic accomplishments in Detroit are a landmark to which they can look with pride. Henry’s $5 day wage transformed economic principles related to employment; his assembly line led to economic growth related to transportation.

The growth of Detroit from a small industrial community to the global capital of the auto industry is inseparable from the ambition of Ford. It is one of resilience and innovation with the conviction that progress must be for everyone. As Douglas Brinkley notes, “Henry Ford didn’t just put America on wheels; he put the world in motion.”18

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 5, 7, 34, 36. ↵

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 35. ↵

- Douglas Brinkley, Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 41, 43. ↵

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 102. ↵

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 103. ↵

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 116. ↵

- Douglas Brinkley, Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 152-153, 155. ↵

- History.com Editors, “Henry Ford and the Model T,” History Channel. Last modified 2023, https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/henry-ford. ↵

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 181. ↵

- Douglas Brinkley, Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 162-163, 170. ↵

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Regional Economic Accounts: Detroit Metropolitan Area.” Accessed 2024. ↵

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 139. ↵

- Douglas Brinkley, Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 125. ↵

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 112, 127. ↵

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Regional Economic Accounts: Detroit Metropolitan Area,” Accessed 2024. ↵

- Douglas Brinkley, Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 519, 520. ↵

- Steven Watts, The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 33. ↵

- Douglas Brinkley, Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 519. ↵

1 comment

Briana Ortega

I really enjoyed this article and how it really showed how Ford’s vision not only built cars but it also transformed society. I liked how the article explained Detroit’s growth with Ford’s inventions, it clearly showed how his success allowed the cities growth. The details on the $5 a day wage and the assembly line helped me understand how revolutionary his ideas were. I found it very interesting how his goal of making affordable cars strengthened the middle class and helped improve the economy. I also like how your article also showed the downside of his invention which helped make the article very realistic.