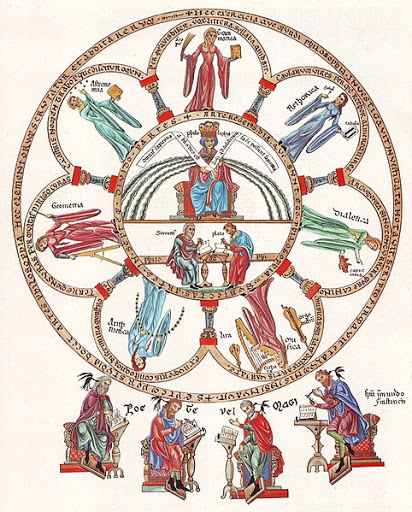

The Seven Liberal Arts. While the phrase “Liberal Arts” is nothing new to any student’s ears, the specific term “Seven Liberal Arts” might not have the same sense of familiarity. The term “liberal arts” comes from the Latin word “liber,” which means “to free”; thus it was believed that the Seven Liberal Arts would “free” one through the knowledge gained in each of various disciplines.1 The term “Seven Liberal Arts” or artes liberales refers to the specific “branches of knowledge” that were taught in medieval schools. These seven branches were divided into two categories: the Trivium and the Quadrivium. The Trivium refered to the branches of knowledge focused on language, specifically grammar, rhetoric, and logic. The second division, the Quadrivium, focused on mathematics and its application: arithmetic, astronomy, geometry, and music.2 Greek philosophers believed the Liberal Arts were the studies that would develop both moral excellence and greater intellect for man. However, it was not from the Greeks, but rather from the Romans that we see the first official pattern or grouping of the Seven Liberal Arts. The beginnings of this pattern came from the Roman teachers Varro and Capella. Varro (116 BCE-27 BCE), a Roman scholar, is credited with writing the first articulation about the Seven Liberal Arts.3 However, Capella (360 AD-428 AD) in his Marriage of Philology and Mercury, set the number and content of the Seven. Branching off of Capella’s work, three more Roman teachers—Boethius, Cassiodorus, and Isadore—were the ones who made the distinctions between the Trivium and Quadrivium.4 Through the writings and research of these men, the foundation for the Seven Liberal Arts was set and ready to be taught officially in the Medieval schools across Europe.

The first division of the liberal arts was called the Trivium which means “the place where three ways or roads meet.” The Trivium was the assembly of the three language subjects or “artes sermoincales”: grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric.5 It was expected that all educated people become proficient in the Latin language. After so many years of school with Latin being the spoken language, the student would be deemed proficient in the language and he would begin studying the higher-level curriculum.6 Completion of the Trivium was equivalent to a student’s modern day bachelor degree.7

The grammar aspect of the Trivium aimed to have students critically analyze and memorize texts as well as produce their own writings. One of the most famous grammatical texts studied by students was the Doctrinale of Alexander of Villedieu, which was a work of verse written in 1199. Naturally, the classics, such as Virgil, were studied as well as some Christian texts.8 In the stronger monasteries, other pagan authors besides Virgil were also studied.9 Not only was Virgil studied, but Donatus and Priscian wrote two very popular textbooks for the study of grammar. Donatus’ work was seen as an elementary work because he focused on the eight parts of speech. Priscian’s work, on the other hand, dealt with more advanced grammatical topics, and he cited some of the Roman forefathers of the Seven, such as Capella, Augustine, and Boethius.10

The student interest level in dialectic had been immense since the early days of the Greek schools, since they focused on the arts of reasoning and logic. For some, such as Rhabanus Maurus, dialectic was considered “the science of sciences.” The commonly studied dialectic textbooks were translations of the famous Greek teacher Boethius’ Categories and De interpretatione of Aristotle. By the twelfth century, the study of dialectic, or logic, came to be seen as the major subject of the trivium.11

The final academic aspect of the Trivium was rhetoric, which focused on expression as well as some aspects of history and law. Again, Boethius had some famous works that were studied in this discipline, but the common textbook was the Artis rhetoricae by Fortunatianus. Grammar and rhetoric were encouraged to a greater extent in the first half of the Middle Ages because knowing Latin was essential.12 The Carolingian period saw the expansion of the discipline of rhetoric grow to include prose composition. This discipline set the groundwork for the studies of canon and civil law in medieval schools.13

The Quadrivium, whose Latin translation is “the place where the four roads meet,” was the assembly of the four mathematical subjects or artes reales: arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy.14 These four areas of study were more advanced than those of the Trivium. Because of this, completion of the Quadrivium would result in the student being awarded a Masters of the Arts degree.15 For Medieval education, all the liberal arts subjects were seen as complementary to ones theology lessons, all of which every educated student would received. The Church encouraged the completion of liberal arts education so strongly that one could not even be ordained a priest if they weren’t deemed proficient in what the Quadrivium demanded.16

The first discipline of the Quadrivium, arithmetic, focused on the qualities of numbers and their operations. When the Arabic notation gained popularity, its methodology was implemented into study, thus increasing the content and understanding of arithmetic.17 The Church had very specific requirements for a man to be deemed proficient in arithmetic. For example, unless a man was able to compute the date of Easter using the writings of the Venerable Bede, he would not be allowed to be ordained into the priesthood.18

The second aspect of the Quadrivium was music. At first, the extensive music courses aspired to produce worship music. Not only did these courses include composition of music, but also performance aspects. The invention and early use of the organ in the medieval churches caused the interest in music to increase.19

Geometry was a new academic aspect for the Medieval world. Up until the tenth century, medieval knowledge of geometry was extremely limited. The discipline focused on geographical and geometrical components. More specifically, the focus was towards the practical applications of surveying, map making, and architecture. The works of Ptolemy were the basis for instruction for geometry. From the work of Ptolemy came further understandings of botany, mineralogy, and zoology.20

The final aspect of the Quadrivium was the teachings of astronomy. However, is was more than understanding how to read the stars. At first, Astronomy was used for arranging the feast days and fast days for the church.17 It also included more complex mathematics and physics. The purpose here was to be able to create and predict the calendar for the church as well as the most advantageous times for harvesting and planting crops. For this discipline, the works of Ptolemy and Aristotle were studied.22

The Seven Liberal Arts. A previously forgotten, but important foundation to our modern-day educational system. The specific disciplines were great, not only from an academic stand point, but in the contributions they held for society. A lot has changed for academia since the medieval period, but if not for the work of our medieval forefathers, how academia changed towards our experiences in the modern day could have been very different.

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts,” by Otto Willmann. ↵

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts,” by Otto Willmann. ↵

- New World Encyclopedia, 2017, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts.” ↵

- S. E. Frost, Essentials of History of Education (New York: Barron’s Educational Series Inc, 1947), 73. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 235; The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts,” by Otto Willmann. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- New World Encyclopedia, 2017, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts.” ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 236. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 236. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 236-237. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 237. ↵

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts,” by Otto Willmann. ↵

- New World Encyclopedia, 2017, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts.” ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 237. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 235. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 237. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 237-238. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 239. ↵

85 comments

Mariana Valadez

I had never known about the origin of the seven liberal arts. It is decent to see where they originate from and how the thoughts became. I feel like you can associate these thoughts into basically every establishment of advanced education. This article was very interesting and engaging. It was very well written and provided me with knowledge I had no idea about.

William Rittenhouse

This was a great article and it had great imagery and the title was also very good. It was nice and straightforward. I think it also has a great amount of detail and I understood it very well. The words flowed well and the word choice was good as well. It was nominated because it was a good article. It should definetely win an award by being nominated. Again, great article and I hope it wins an award. It deserves one.

Stephanie Nava

I never looked into the origin of the seven liberal arts. It is nice to see where they come from and how the ideas came to be. I feel like you can connect these ideas into pretty much every institution of higher education, at St. Mary’s, I resemble some of these with some of the core classes that are required. You would think that these ideas came about during the renaissance period, but the fact that they date all the way back to the medieval era is amazing.

Rylie Kieny

This was an interesting read as it explained the foundation for todays modern curriculum. Before college I never really knew what liberal arts meant. I had heard of liberal arts colleges before but had no idea what that meant or looked like. The article has great structure and makes it easy for the reader to follow ideas and absorb them as they read. I think this can also tell educators something about the evolution of academics. We have been basing our studies off things that happend so long ago. It may be time for change and new ideas!!

Engelbert Madrid

One of the reasons why the Renaissance Period remains to be an important period throughout the aspects of education, science, religion, and politics is because of the new concepts and ideas that were developed by wise experts. For example, although the seven specific liberal arts are not well-recognized by students and teachers, the educational curriculum in many countries follow what was developed by Roman and Greek teachers. The article does a phenomenal job on providing good details and information about the seven specific liberal arts.

Natalie Thamm

This was a really cool and interesting article. I had never stopped and thought about the origins of liberal arts, though I had understood the purposes. The author did a really great job of going through the seven of the liberal arts and explaining what they looked like at the time and why they were seen as important, as well.

Angel Torres

The article did a great job of keeping the reader engaged, especially when to comes to subject that is hard to grasp. Furthermore, the article was very informative on the seven liberal arts. I never knew there was seven types of liberal arts nor knew that they were separated into two, the trivium and quadrivium. Its also quite fascinating how liberal arts education today gets its foundation from quite some time ago.

Emily Jensen

I enjoyed this article for several reasons. I can remember being confused about what a liberal arts education was before I started college, so I liked that there was a topic to explain that. I really liked this article because it explained the 7 specific liberal arts that guide most higher education. I recognized several of the Catholic themes presented by the author. This was a great read!

Hailey Stewart

I like the structure of the “Seven Liberal Arts.” As an engineering major with a brief artistic background, I find this structure of education appealing, as well as the structure of the article which compliments this topic well. I think this topic is reminiscent of the teachings of Latin in schools today. Latin is the foundation of languages, in the same way that the liberal arts are the foundation for how we live our lives. Great read!

Aneesa Zubair

Modern-day students have all heard of liberal arts, but we don’t always think about what that term means or where it came from. I knew the concept of a liberal arts education first took shape in ancient Rome, but I had never heard of the seven liberal arts or Quadrivium and Trivium. Though those terms aren’t used today, the subjects, like music, rhetoric, and language, and even some of the material studied, like Ptolemy and Virgil, are the same, which is really fascinating!